The COVID-19 pandemic triggered an unprecedented recession, unique in U.S. history for its swift onset and equally rapid recovery. Beginning in February 2020, the economic downturn reached depths unseen in a century but rebounded within a mere two months, as declared by the National Bureau of Economic Research. This remarkable turnaround was propelled by substantial fiscal interventions, the swift rollout of vaccines, and the underlying resilience of the U.S. economy, leading to an economic expansion now in its fourth year. As the U.S. economy demonstrates continued growth, two key features have become apparent: first, the U.S. successfully avoided the prolonged economic hardship that plagued many American families during the previous recovery; and second, the pace of the U.S. recovery has significantly surpassed that of most G10 nations. This analysis will delve into Us Inflation Compared To Other Countries, examining the factors contributing to these divergent economic paths.

The recovery period following the Great Recession was notably hampered by economic scarring, largely due to insufficient fiscal support for both households and businesses. In that era, consumer spending was slow to return to pre-crisis levels, resulting in a significant output gap that suppressed inflation but also curtailed labor demand. Consequently, depressed employment figures led to workforce discouragement and labor force exits, with many individuals struggling to regain their pre-recession income levels. This environment kept consumption and residential investment low, and the gap between potential and actual GDP persisted.

In contrast, in response to the pandemic, many of the United States’ global competitors mirrored the insufficient policy response of the previous recovery. As the global economy grappled with ongoing disruptions from COVID-19 in 2021 and beyond, numerous foreign governments opted for premature fiscal tightening, resulting in policy responses that were too weak to effectively restore their economies to pre-recession levels. Conversely, U.S. policymakers adopted a more expansive approach to countercyclical support, enacting substantial relief measures under both Democratic and Republican administrations. These measures were designed to extend aid well beyond the initial waves of the pandemic, encompassing even the omicron and delta variants. As a result, unlike in Europe where economic activity is once again lagging behind its pre-pandemic trajectory, the U.S. economy currently exhibits no significant slack. Notably, U.S. labor force participation has climbed to historic highs across major demographic groups, particularly among prime-age women. While elevated inflation was observed in 2021 and 2022, it subsided relatively quickly and was primarily attributable to supply-side constraints in the housing market rather than fundamental demand-supply imbalances. The consistent decline in non-shelter year-over-year inflation, currently at a mere 1.1%, highlights that supply disruptions—not an overheated economy—were the primary drivers of high inflation in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. Overall, the post-COVID recovery validates the crucial decisions made by U.S. policymakers and ultimately justifies the chosen policy direction.

Avoiding an Output Gap: A Key to US Recovery

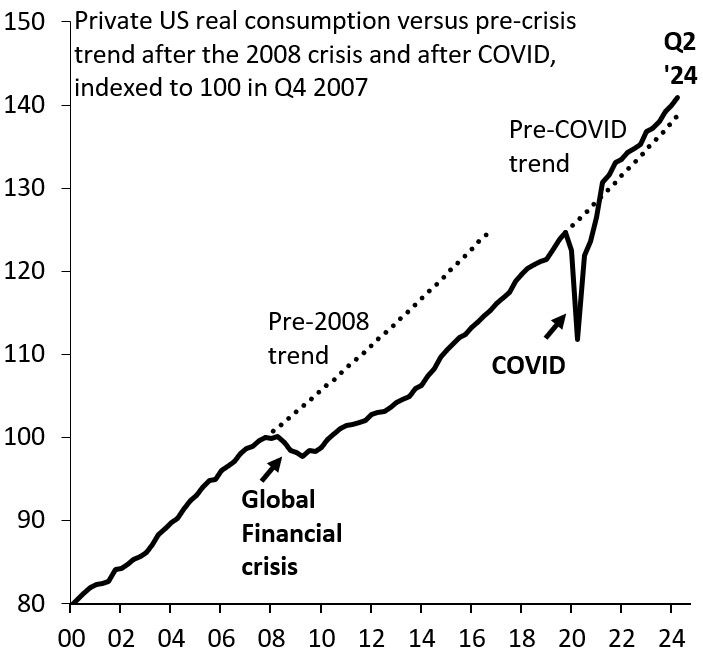

A pivotal factor in the U.S. recovery’s relative strength is the avoidance of a substantial output gap following the COVID-19 shock. Unlike the period after the 2008 global financial crisis, where the U.S. economy struggled to regain its pre-2008 growth momentum, the robust fiscal support in 2020 and 2021 effectively sustained economic activity at pre-recession levels, barring a temporary dip during widespread lockdowns. While measuring output gaps is inherently complex, extrapolating from the pre-2008 growth trend suggests a considerable slack in the decade following the Great Recession (Figure 1). This significant output gap contributed to persistently low inflation in the subsequent years and led to labor force discouragement and exits, hindering the recovery of household balance sheets and the national housing market.

The pandemic posed a risk of repeating this pattern, especially with widespread closures in the service sector. However, aggressive fiscal stimulus prevented this outcome. Pandemic-relief legislation was specifically designed to maintain payrolls while also providing substantial financial and in-kind support to households. This level of support in the U.S. far exceeded that provided by other G10 nations, resulting in the U.S. significantly outperforming its peers. Indeed, private consumption in the U.S. has grown at a faster pace than in the rest of the G10, both in absolute terms and per capita (Figure 2). Had the U.S. economy grown at the median rate of the G10 since Q2 2021, its GDP would be cumulatively three percentage points lower by Q2 2024, underscoring the crucial impact of the aggressive policy approach in preventing a material output gap.

Figure 1. Private US real consumption vs. precrisis trend after the 2008 crisis and after COVID-19

Source: Haver Analytics

Figure 2. Real private consumption across the G10

Source: Haver Analytics

A Strong and Inclusive Labor Market Recovery

The absence of a significant output gap in the U.S. fueled a tight labor market and rapid employment growth. Labor force participation among prime-age men (Figure 3) and women (Figure 4) has either fully recovered or surpassed pre-pandemic levels. This labor market rebound is a stark contrast to the decade following the global financial crisis, which saw discouraged workers leave the labor force, causing a notable decline in participation rates. The current rise in prime-age female labor force participation across all demographic groups is particularly noteworthy, reaching historic highs. The U.S. labor market demonstrates no signs of the scarring that was evident after 2008, a remarkable achievement considering the severe impact of COVID-19 on numerous service-providing occupations.

Figure 3. Labor force participation rates for men aged 25-54

Source: Haver Analytics

Figure 4. Labor force participation rates for women aged 25-54

Source: Haver Analytics

In an international comparison, the U.S. rebound in labor participation is especially pronounced, particularly after a more subdued recovery in 2021. As illustrated in Figure 5, labor force participation declined across the G10 in 2020, and the U.S. initially lagged in recovery during 2021. However, U.S. participation experienced a rapid resurgence in 2022 and 2023, now aligning with G10 peers.

Figure 5. Labor force participation rates for the prime-age population (25-54) across the G10

Source: Haver Analytics

The Inflation Trade-off: US vs. G10

The elevated post-pandemic inflation experienced in the U.S. can be analyzed in two distinct phases. The initial phase, from the end of the recession in April 2020 to June 2022, saw core CPI grow at an annualized rate of 4.8%, primarily driven by pandemic-induced supply chain pressures. While these supply chain disruptions affected many countries, weaker economic growth in some nations helped to moderate inflation compared to the U.S. This demonstrates the initial phase of US inflation compared to other countries was notably higher.

The second phase, spanning from June 2022 to May 2024, was characterized by rising shelter costs as the main inflationary driver, rather than generalized inflation. During this period, core CPI in the U.S. remained elevated, fluctuating between 6.6% and 3.4% year-over-year, with housing costs being the primary contributor (Figure 6). The surge in housing costs was largely due to insufficient housing construction both during and before the pandemic, influenced by factors such as stringent local zoning laws that restrict new and denser housing construction, and elevated mortgage rates that deterred homeowners from listing their properties.

Figure 6. Core CPI inflation broken down into contributions from shelter and other

Source: Haver Analytics

An international perspective on inflation is presented in Figure 7, which directly addresses US inflation compared to other countries. Inflation in the U.S. was higher relative to the G10 in the first two years of the pandemic but reversed trend starting in early 2022. Inflation in the U.S. began to decline and, for a period, was lower than in the U.K., the Eurozone, and the G10 median. Currently, cumulative core inflation in the U.S. is roughly comparable to most major competitors, except for Japan. However, the unique aspect of the U.S. experience is that while inflation levels were similar to other developed economies, the growth in GDP, consumption, and employment was exceptionally strong compared to competitors.

Figure 7. Core CPI inflation across the G10

Source: Haver Analytics

The US Investment Boom: Outpacing the G10

Investment in the U.S. has emerged as a significant area of strength compared to other G10 economies. Fueled by investment incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, along with broader optimism surrounding the U.S. economy, the nation has experienced a relative investment boom. As shown in Figure 8, investment, measured by real gross capital formation, was particularly robust in Canada and the U.S. through 2022. Subsequently, in 2023 and 2024, U.S. investment accelerated further relative to its peers. Currently, U.S. investment stands 14% above pre-COVID levels, while investment in the Eurozone has declined by 7% over the same period. This highlights a crucial divergence when considering US inflation compared to other countries – the US managed higher growth and investment despite similar inflation levels.

Figure 8. Real gross fixed capital formation across the G10

Source: Haver Analytics

The absolute increase in U.S. investment becomes even more significant when adjusting for the business cycle. Analysis from the U.S. Treasury Department indicates that investment typically decreases (as a share of GDP) following a business cycle peak, generally falling by about 1 percentage point between six and twelve quarters post-peak. However, in the current recovery, aggregate investment has remained relatively stable, resulting in an estimated $430 billion in additional investment compared to historical trends.

Conclusion: Policy Choices and Economic Outcomes

In summary, during the pandemic, policymakers faced a critical decision regarding fiscal stimulus. One path involved implementing aggressive fiscal measures to avert lasting economic damage and sluggish growth, while accepting the risk of elevated inflation due to unusual supply chain disruptions. The alternative was to adopt a more restrained fiscal approach, potentially leading to output gaps and slow consumption growth, which might help mitigate inflationary pressures. The U.S. chose the former strategy, while most other G10 nations opted for the latter. Consequently, the U.S. has experienced significantly greater economic growth and investment, accompanied by slightly higher price levels in the initial phases of the recovery. When assessing US inflation compared to other countries, it is evident that while the US did experience a period of higher inflation, this was counterbalanced by stronger economic performance and a more robust recovery than its G10 counterparts. This outcome suggests a successful navigation of the challenging economic landscape by U.S. policymakers, prioritizing strong recovery and investment even amidst global inflationary pressures.