INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented a global health crisis, with the SARS-CoV-2 virus continuing to evolve and pose challenges worldwide [1]. Despite the global impact, a striking paradox has emerged when comparing COVID-19 mortality rates between the United States and Africa. As of October 1, 2023, African countries, encompassing 55 nations, reported a COVID-19 mortality rate almost 4.5 times lower than that of the United States, despite having a population over 4.2 times larger [3]. This disparity is further highlighted by comparing Nigeria, a densely populated nation with limited vaccination and mandates, to Israel, a smaller country with high vaccination rates and strict mandates. Nigeria has experienced approximately four times fewer COVID-19 deaths than Israel. Haiti, with a minimal vaccination rate of only 5%, has also shown a surprisingly low COVID-19 burden [3]. This article aims to explore the potential reasons behind this mortality paradox, drawing upon academic, clinical, and social observations.

Western nations, particularly the United States, heavily relied on rapid development and deployment of nucleic acid-based vaccines (mRNA and adenoviral vector) and novel antiviral drugs like remdesivir, molnupiravir, and Paxlovid [10-12]. These interventions were swiftly approved and distributed in wealthier countries, often despite concerns about their risk-benefit profiles [11], potential for driving viral evolution [3], and accelerated approval processes [9, 13]. In contrast, many African nations, including Egypt, initially lacked access to these novel interventions. This lack of access, coupled with a different approach to treatment, may have inadvertently contributed to the observed mortality differences.

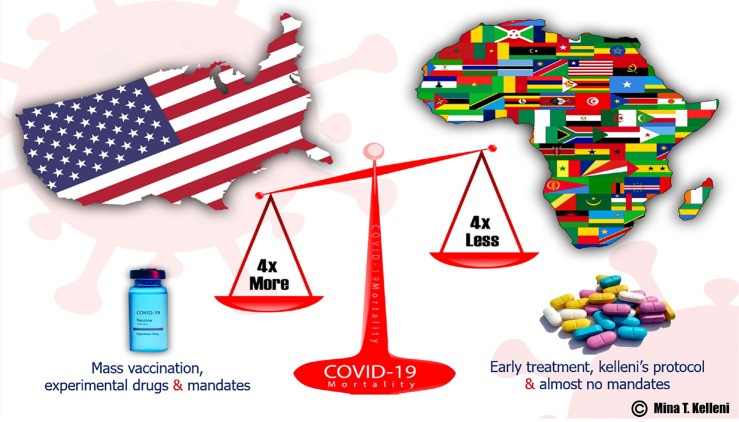

The coronavirus disease 2019 mortality paradox. The United States has tackled coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by heavily relying on mass vaccination, rapidly approving experimental drugs and implementing strict mandates. In contrast, Africa has chosen to adopt early treatment using safe repurposed drugs as best scientifically revealed in Kelleni’s protocol and has abandoned mass vaccination and mandates. Despite Africa having a population over four times larger than the United States, its COVID-19 death toll has been four times lower.

The coronavirus disease 2019 mortality paradox. The United States has tackled coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by heavily relying on mass vaccination, rapidly approving experimental drugs and implementing strict mandates. In contrast, Africa has chosen to adopt early treatment using safe repurposed drugs as best scientifically revealed in Kelleni’s protocol and has abandoned mass vaccination and mandates. Despite Africa having a population over four times larger than the United States, its COVID-19 death toll has been four times lower.

Figure 1: COVID-19 Mortality Paradox: Comparing the United States and Africa’s Approaches and Outcomes.

KELLENI’S PROTOCOL AND EARLY TREATMENT SUCCESS IN AFRICA

Early in the pandemic, a different approach to COVID-19 management emerged in Africa, exemplified by the development and implementation of Kelleni’s protocol in Egypt. This protocol, focused on early treatment using repurposed, safe, and readily available drugs, stands in stark contrast to the Western emphasis on novel vaccines and pharmaceuticals. Kelleni’s protocol prioritizes immune modulation and early intervention, utilizing drugs like nitazoxanide, NSAIDs, and azithromycin [16-19].

The author’s initial attempts to share insights on early treatment, including the potential of NSAIDs like ibuprofen, were met with resistance from Western medical journals [16, 17]. However, research highlighting the efficacy and safety of nitazoxanide, a key component of Kelleni’s protocol, was eventually published [19]. Despite the compelling evidence and consistent success in managing COVID-19 patients across various demographics in Egypt [16, 18, 20-23], calls for randomized clinical trials of Kelleni’s protocol and broader consideration of early treatment strategies were largely ignored by Western scientific and health authorities. This dismissal, according to the author’s perspective, suggests a potential bias towards novel pharmaceutical interventions over repurposed drugs and a prioritization of political and economic interests over patient-centered care in Western healthcare systems.

In practice, clinicians in Africa who adopted Kelleni’s protocol reported significant success in treating COVID-19 patients, including those with severe illness and comorbidities, particularly when treatment was initiated early and before exposure to remdesivir or high-dose corticosteroids [21, 23, 25]. This real-world experience further underscores the potential of early treatment approaches in managing COVID-19, contrasting with the higher mortality rates observed in countries heavily reliant on vaccination and late-stage interventions.

CONTRASTING HOSPITAL PROTOCOLS AND PHARMACEUTICAL APPROACHES

A significant observation in the African context was the correlation between Western-style hospital protocols and poorer outcomes. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in Egypt, celebrities and high-ranking officials treated in hospitals following Western protocols, which often included remdesivir and dexamethasone, experienced higher rates of mortality or disability [24]. Conversely, geriatric and comorbid patients managed at home with Kelleni’s protocol showed considerably better outcomes [21, 25].

Furthermore, the rapid introduction and widespread use of expensive novel drugs, including monoclonal antibodies, favipiravir, and molnupiravir, in the Western pharmaceutical market, contrasted with the more cautious and resource-conscious approach in many African nations. The author argues that the Western pharmaceutical industry may have profited significantly from the pandemic by promoting fear and expensive, potentially less effective, treatments, while suppressing or ignoring alternative approaches like early treatment with repurposed drugs. This perspective raises critical questions about the influence of pharmaceutical industry interests on public health policies and treatment guidelines in Western countries.

The author’s personal experiences with censorship on social media platforms for questioning the “perfectly safe and effective” narrative surrounding nucleic acid-based vaccines highlight the challenges in dissenting from mainstream narratives and the potential suppression of alternative scientific viewpoints during the pandemic. Despite repeated attempts to engage with Western stakeholders, including politicians and journalists, regarding the potential benefits of early treatment and the risks associated with mass vaccination and novel drugs, responses were largely absent, indicating a potential systemic resistance to considering alternative approaches.

AFRICA’S DEFIANCE OF MANDATES AND TRUST IN NATURAL IMMUNITY

In contrast to the often-strict mandates implemented in many Western nations, African countries generally exhibited a more relaxed approach. Mask mandates and vaccine mandates were less stringent or consistently enforced, and a greater emphasis was placed on individual choice and natural immunity. This difference in public health strategy may reflect cultural values, resource limitations, or a different risk perception.

The author recounts personal experiences in Egypt, where mask-wearing was not widely adopted, and there was a greater reliance on natural immunity. While some African governments attempted to promote vaccination, resistance was encountered, and concerns arose regarding potential coercion and lack of transparency surrounding vaccine risks and liabilities. The observation of adverse events following vaccination in young, healthy individuals in Africa, mirroring reports from Western countries [11], further fueled skepticism towards mandatory vaccination campaigns.

Despite the pressure to adopt Western vaccination strategies, some healthcare workers in Africa reportedly facilitated access to vaccination certificates while discreetly discarding vaccines, suggesting a level of quiet resistance to mandates and a potential prioritization of individual autonomy and perceived patient safety. This nuanced response to vaccine mandates within the African healthcare system highlights the complexities of implementing global health policies in diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts.

HEALTHIER LIFESTYLES AND NATURAL IMMUNITY IN AFRICA

Beyond specific treatment protocols and public health policies, broader lifestyle and environmental factors may contribute to the observed COVID-19 mortality differences between the United States and Africa. Despite economic challenges, access to affordable, nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables is often greater in many African countries [37]. Lower levels of pollution and obesity, coupled with potentially stronger social support networks and spiritual well-being, may contribute to enhanced baseline natural immunity in African populations compared to their Western counterparts. These factors, while difficult to quantify precisely, warrant consideration when seeking to understand the complex interplay of factors influencing COVID-19 outcomes across different regions.

CONCLUSION: A TALE OF TWO APPROACHES

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed a stark contrast in approaches and outcomes between the United States and Africa. While the United States heavily invested in and relied upon novel vaccines, pharmaceutical interventions, and mandates, Africa, often by necessity, adopted a different path, emphasizing early treatment with repurposed drugs and exhibiting greater resilience to mandates. The lower COVID-19 mortality rates observed in Africa, despite a larger and often more vulnerable population, present a compelling paradox that challenges the dominant Western narrative of pandemic response.

Kelleni’s protocol and the broader African experience with early treatment offer a potentially valuable counterpoint to the Western model, suggesting that safe, affordable, and readily available repurposed drugs, combined with a focus on strengthening natural immunity, may represent a viable and ethical approach to managing viral pandemics. The author contends that a critical examination of the potential influence of political, economic, and pharmaceutical industry interests on Western COVID-19 policies is warranted. Furthermore, acknowledging and learning from the diverse experiences and outcomes across different regions, including the successes observed in Africa, is crucial for developing more effective, equitable, and patient-centered global pandemic preparedness and response strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author acknowledges the historical example of Saint Athanasius of Alexandria and the resilience of the Coptic community in standing against powerful forces in defense of their beliefs. Gratitude is also expressed to OSF Preprints for pre-publication of an earlier version of this work.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 4, 2023

First decision: December 6, 2023

Article in press: January 4, 2024

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu YC, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

References

[1] Kelleni MT. Field of Vision perspective: COVID-19 mortality paradox: United States Compared To Africa. World J Virol 2024; In press. [DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v13.i1. In press]

[2] Kelleni MT. The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Time to learn or repeat previous mistakes? World J Virol 2022; 11: 1-12 [PMID: 35155450 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v11.i1.1]

[3] Worldometer. Coronavirus Update (Live): 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

[4] World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2020.

[5] Sumner A, Hoy C, Ortiz-Juarez E. Estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty. WIDER Working Paper 2020/126. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER; 2020.

[6] Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Cohen Silver R, Everall I, Ford T, John A, Kabir T, King K, Madan I, Michie S, Przybylski AK, Shafran R, Sweeney A, Worthman CM, Yardley L, Bullmore E, Gillan CM. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: 547-560 [PMID: 32396790 DOI: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1]

[7] Ioannidis JPA. Lockdowns, vaccines, and the test of mandates. Brownstone Institute 2022. Available from: https://brownstone.org/articles/lockdowns-vaccines-and-the-test-of-mandates/

[8] Rancourt DG. Masks Don’t Work: A review of science relevant to COVID-19 social policy and Why Face Masks Fail: Evidence Review. Research Gate 2020. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.3645.4912

[9] Thacker PD. COVID-19: Researcher blows the whistle on data integrity issues in Pfizer’s vaccine trial. BMJ 2021; 375: n2635 [PMID: 34794823 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n2635]

[10] Kelleni MT. Favipiravir in COVID-19: Is it another nail in the coffin of evidence-based medicine? World J Virol 2021; 10: 1-7 [PMID: 33542759 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v10.i1.1]

[11] Kelleni MT. Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination: Bioethics, law and human rights. World J Vaccines 2023; 13: 1-21 [DOI: 10.4236/wjv.2023.131001]

[12] Kelleni MT. Molnupiravir for COVID-19: Another drug with outbalanced risk-benefit ratio? World J Virol 2022; 11: 13-23 [PMID: 35155451 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v11.i1.13]

[13] Doshi P. Pfizer and Moderna’s “95% effective” vaccines—we need more details and the raw data. BMJ 2021; 371: n2635 [PMID: 33330885 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n2635]

[14] Kyriakopoulos C, McCullough PA. Long-term adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines: the dark side of mRNA vaccines. J Clin Med 2023; 12: 1962 [PMID: 36983272 DOI: 10.3390/jcm12051962]

[15] Gohil S, Le NT, Andreu-Perez J, Morgunov K, Sharma A, Vajravelu R, Nguyen T, Wang L, Pourmand N, Loor JJ. Meta-analysis of all-cause mortality in randomized controlled trials of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use in the United States. Trials 2023; 24: 157 [PMID: 36797747 DOI: 10.1186/s13063-023-07153-4]

[16] Kelleni MT. Could nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs resolve the cytokine storm of COVID-19? Drug Des Devel Ther 2020; 14: 1745-1748 [PMID: 32546935 DOI: 10.2147/DDDT.S259884]

[17] Kelleni MT. Ibuprofen and COVID-19. Lancet 2020; 395: 1247-1248 [PMID: 32305064 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30848-9]

[18] Kelleni MT. Kelleni’s protocol for early outpatient treatment of COVID-19. J Adv Res 2021; 28: 1-12 [PMID: 34976837 DOI: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.12.010]

[19] Kelleni MT. Nitazoxanide is best suitable for early global management of COVID-19. Pharmacol Rep 2020; 72: 697-705 [PMID: 32320847 DOI: 10.1007/s43440-020-00105-4]

[20] Kelleni MT. Expanded Kelleni’s protocol for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. World J Virol 2022; 11: 24-34 [PMID: 35155452 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v11.i1.24]

[21] Kelleni MT. Successful management of geriatric COVID-19 patients using Kelleni’s protocol. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9: 670-678 [PMID: 33598644 DOI: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i3.670]

[22] El-Demerdash Y, El-Kholy G, Kelleni M, El-Sayed RM, El-Kenawy AE, Gaber OA, El-Saber B, El-Araby H, El-Abd S, Barakat K. Nitazoxanide efficacy against COVID-19: Molecular docking, in vitro, and randomized clinical trial studies. J Med Virol 2021; 93: 1818-1826 [PMID: 32886365 DOI: 10.1002/jmv.26553]

[23] Elzalabany MM, Metwally AA, Saad AS, Mostafa HI, Kelleni MT, El-Demerdash Y, El-Araby H. Efficacy and safety of nitazoxanide in treatment of mild COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 717-724 [PMID: 33275110 DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkaa518]

[24] Kelleni MT. Dexamethasone and remdesivir for COVID-19: Are we moving a step forward or two steps backward? World J Virol 2020; 9: 1-7 [PMID: 33381597 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v9.i1.1]

[25] Kelleni MT. Personalized Kelleni’s protocol for management of severe COVID-19 pneumonia case. World J Crit Care Med 2021; 10: 1-7 [PMID: 33585828 DOI: 10.5492/wjccm.v10.i1.1]

[26] El-Demerdash Y, Ibrahim AK, Ibrahim NA, Gomaa W, Barakat K, Kelleni M. Nitazoxanide modulates NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB signaling pathways in HepG2 cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2018; 65: 311-320 [PMID: 30342306 DOI: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.10.021]

[27] Kelleni MT. Kelleni’s protocol for early outpatient treatment of COVID-19: Update and clinical experience. World J Virol 2023; 12: 1-12 [PMID: 36777585 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v12.i1.1]

[28] Kelleni MT. The “updated” COVID-19 vaccines: Are they really updated? World J Virol 2023; 12: 13-23 [PMID: 36777586 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v12.i1.13]

[29] Kelleni MT. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine and COVID-19: Is it time for repurposing? World J Virol 2020; 9: 8-16 [PMID: 33381598 DOI: 10.5501/wjv.v9.i1.8]

[30] Sachs JA, Piller R, Muhlebach MD. The origin of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet 2022; 399: 3-4 [PMID: 34990685 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02858-5]

[31] Hause AM, Lai CJ, Pollock BD, Hause BM. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: lessons learned from the pre-authorization clinical trials. Cureus 2023; 15: e34380 [PMID: 37288055 DOI: 10.7759/cureus.34380]

[32] Fraiman J, Bridle C, Dalgalarrondo V, Durieux E, Lambert JB, Bentayou VM, Whelan M, Faria N, Baudin M, Kaiser D, MacMahon G, Yimsut K, Benn P, Kostoff RN. Serious adverse events of special interest following mRNA vaccination in randomized trials. Vaccine 2022; 40: 5798-5805 [PMID: 36055877 DOI: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.08.036]

[33] McLaughlin J, Doshi P. COVID-19 vaccines: why are trials underpowered for harms, and how should we address this? BMJ Evid Based Med 2021; 26: 105-108 [PMID: 33758076 DOI: 10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111679]

[34] Sheikh AB, Khan M, Vattoth S, Agrawal P, Kamal A, Cocco N, Tahir MJ, Chuku O, Singh B, Singh S, Khosa F, Nasir MU, Chughtai KA. Myocarditis and pericarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccines: what do we know so far? Cureus 2021; 13: e16794 [PMID: 34557455 DOI: 10.7759/cureus.16794]

[35] Meyts ER, Lidegaard Ø. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and the risk of myocarditis in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2023; 38: 1-10 [PMID: 36243867 DOI: 10.1007/s10654-022-00958-3]

[36] Hotez PJ. Mounting antiscience aggression in the United States. Microbes Infect 2023; 25: 104807 [PMID: 36682046 DOI: 10.1016/j.micinf.2023.104807]

[37] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT database: 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data