Introduction

Understanding body weight and height is fundamental in public health research, often used to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI) and assess obesity prevalence. While direct, standardized measurements are ideal, many large-scale studies, especially those requiring broad population coverage, rely on self-reported data for height and weight. This reliance stems from practical limitations related to cost and logistics. However, existing research indicates a tendency for individuals to overstate their height and understate their weight when self-reporting. This misreporting can introduce bias into BMI estimations and consequently, obesity prevalence rates derived from these self-reported measures [1, 2].

In the United States, three major national surveys provide representative data on adult height, weight, BMI, and obesity: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). NHANES and NHIS are conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, while BRFSS is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and various US states and territories. All three surveys are designed to represent the non-institutionalized civilian US population and collect self-reported height and weight. Notably, NHANES also includes measured height and weight data, offering a unique opportunity to compare self-reported and measured values within the same survey. Previous studies using NHANES data have extensively explored factors influencing misreporting, such as age, gender, actual height or weight, recent medical visits, and health history [3-10].

Given that these surveys aim to represent the same population during overlapping periods, one would expect a degree of consistency in their estimates. Indeed, prior research has demonstrated reasonable agreement across these surveys for various health conditions [11-18]. Grabner [19] previously utilized data from all three surveys (1970s-2008) to analyze BMI trends in specific demographic groups (White, Black, and Hispanic adults aged 20-74).

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of height, weight, BMI, and obesity prevalence derived from these three national surveys in the US, spanning from 1999 to 2016. We leverage both self-reported and measured data from NHANES, alongside self-reported data from NHIS and BRFSS, to investigate the discrepancies. Our study goes beyond simple mean comparisons, delving into how self-reported data in NHANES contrasts with self-reported data from other surveys across dimensions like height, weight, BMI distributions, and obesity prevalence. It is crucial to understand that similar mean BMI values across surveys do not guarantee similar obesity prevalence rates. This paper offers a comprehensive examination of these critical issues in height and weight data collection and interpretation.

Methods

Survey Descriptions

NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey): NHANES employs a rigorous methodology, combining in-home interviews with standardized physical examinations conducted in mobile examination centers. Since 1999, NHANES has operated continuously, releasing data in two-year cycles. Each cycle samples a nationally representative cross-section of the US civilian non-institutionalized population using a complex, stratified, multistage probability cluster design. For the 2015-2016 cycle, the interview and examination response rates were 61% and 59%, respectively. Detailed information about NHANES methodology is publicly available [20] and on the CDC website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

NHIS (National Health Interview Survey): NHIS is a household survey that collects data on a broad spectrum of health topics through in-person interviews [21, 22]. Basic demographic information is gathered from a family respondent, followed by more detailed health questionnaires administered to randomly selected adult and child samples. Telephone follow-ups are sometimes conducted. In 2016, the adult sample component response rate was 54.3%. Since 2006, NHIS data releases indicate if any part of the interview was conducted via telephone. Analysis reveals that between 2006 and 2016, approximately 22.5% of respondents had a portion of their interview conducted by phone. NHIS content is updated periodically (every 10-15 years) and provides essential data for tracking health status, healthcare access, insurance coverage, health-related risk factors, and progress toward national health objectives. Further details are available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm.

BRFSS (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System): Established in 1984 and nationwide since 1993, BRFSS is a state-based telephone survey system [23]. It collects data on health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, healthcare access, and preventive service utilization. In 2011, BRFSS incorporated cell phone inclusion and refined statistical weighting methods. The 2016 landline and cell phone response rates were 48% and 46%, respectively. Extensive information on BRFSS design and methodology can be found at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

For this study, we utilized NHANES data from nine 2-year cycles (1999-2000 through 2015-2016) and annual data from NHIS and BRFSS for the same period. All data were obtained from publicly accessible, anonymized data files. The total sample sizes were substantial: 43,320 for NHANES, 510,620 for NHIS, and 6,200,791 for BRFSS. Year-specific sample sizes are detailed in Supporting Information Table S1.

Weight and Height Data Collection

In NHANES, both self-reported and measured weight and height data are collected. Self-reported data is gathered during an in-person household interview. Participants are informed that a physical examination at a mobile center, occurring weeks later, will include standardized measurements of height and weight [20]. NHIS collects self-reported weight and height through in-person household interviews. BRFSS collects self-reported data via telephone interviews. The specific wording of height and weight questions in each survey is provided in Supporting Information Table S2.

NHANES employs data quality control measures. Measured and self-reported height and weight values falling outside the 1st and 99th percentiles for specific age or age-gender groups are flagged for review. Unrealistic values (less than 10 per survey cycle) are set to missing. Original body measurement data remain unchanged, and no imputation is performed. BMI values were calculated by the researchers from both measured and self-reported NHANES data.

NHIS data release procedures involve setting extreme height and weight values to “not available” for confidentiality. For 2006-2016, this applied to height < 59 inches or ≥ 76 inches, or weight < 100 lb or ≥ 299 lb. For 1999-2005, slightly different thresholds were used. BMI is calculated by NHIS for all respondents with valid height and weight data, even if specific height and weight values are masked in public files. Extremely high/low weight (< 50 or > 500 lb) and height (< 24 inches or > 95 inches) are considered invalid.

BRFSS also sets extreme height and weight values to missing in public data files for quality reasons. For 2011-2016, exclusions were for height < 3 feet or ≥ 8 feet and weight < 50 lb or ≥ 650 lb. Prior to 2011, different exclusion criteria were used. These missing values are not used for BMI calculation in public BRFSS data files.

It’s important to note that BMI and obesity prevalence are secondary variables, calculated from reported weight and height. Obesity is consistently defined as BMI ≥ 30 across all surveys. All analyses are stratified by sex due to known sexual dimorphisms in body composition [24] and sex-specific reporting differences [1].

Statistical Comparisons

This study compared weight, height, BMI, and obesity prevalence across the three surveys. Differences are visually represented in figures. Sex-specific graphical comparisons are presented for measured and self-reported data from NHANES, and self-reported data from NHIS and BRFSS across all survey years. NHANES data points are plotted at the midpoint of 2-year intervals. The ratio of age-adjusted obesity prevalence in men to women was calculated for each year to compare sex differences across surveys. Statistical significance testing was not conducted for comparisons of self-reported data across surveys.

Statistical Methods

Obesity prevalence estimates were age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population using direct standardization across three age groups (20-39, 40-59, 60+ years). Pregnant women were excluded from all analyses. SAS 9.4 and SUDAAN 11.0.0 were used for statistical analyses. Sampling weights, provided by each survey to account for complex sampling design and non-response, were applied in all analyses. Although all surveys are weighted to be nationally representative, slight differences exist in their sample designs and weighting procedures [21-23, 25, 26].

Supplemental NHANES Analyses

Within NHANES, differences between self-reported and measured weight, height, BMI, and obesity prevalence are detailed in Supporting Information Tables S3-S6. Regression analyses were conducted to assess the associations of survey cycle, age group (<60 and ≥60 years), and measured height with the difference between self-reported and measured height, stratified by sex. Similarly, linear regression models examined the associations of survey cycle, age group, and measured weight (categorized by obesity status: BMI < 30 and BMI ≥ 30) with differences in self-reported and measured weight or BMI. Logistic regression models assessed the associations of survey cycle and age group with differences in obesity prevalence estimates between self-reported and measured values. Results are summarized in Supporting Information Table S7. All NHANES analyses incorporated sampling weights and accounted for the complex sample design. Standard errors were estimated using Taylor series linearization in SUDAAN. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

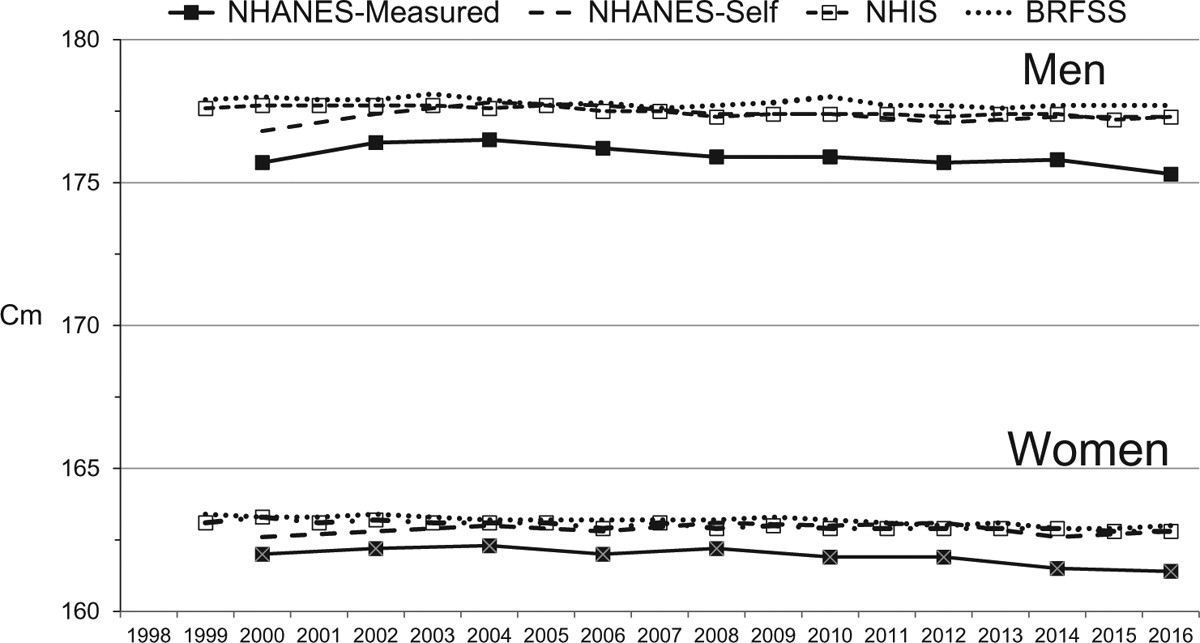

Height Comparison

Figure 1 illustrates that in every survey year, mean self-reported heights from all three surveys were greater than mean measured heights from NHANES for both men and women. Self-reported heights in BRFSS and NHIS were similar to, but slightly higher than, NHANES self-reported heights. For men, the mean differences in self-reported height compared to NHANES self-reported height were 0.1 cm in NHIS and 0.4 cm in BRFSS. For women, these values were 0.1 cm and 0.3 cm, respectively.

Figure 1.

Mean height by survey, 1999 through 2016.

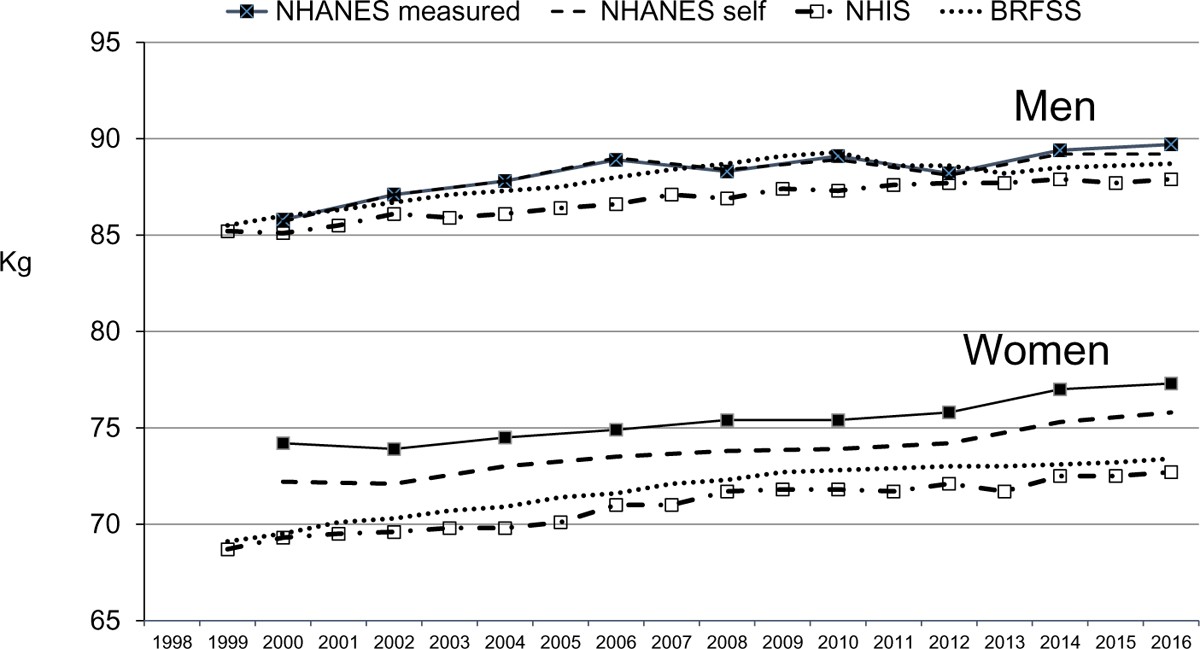

Weight Comparison

Weight comparisons revealed sex-specific patterns (Figure 2). For women, mean self-reported weights in all three surveys were consistently lower than mean measured weights in NHANES across all survey cycles. Furthermore, self-reported weights in NHIS and BRFSS were lower than self-reported weights in NHANES. Specifically, women’s mean self-reported weights in NHIS were 2.8 kg lower and in BRFSS were 1.9 kg lower compared to NHANES self-reported weights.

Figure 2.

Mean weight by survey, 1999 through 2016.

For men, differences were less pronounced and systematic. In general, mean self-reported weights in NHIS and BRFSS tended to be slightly lower than NHANES self-reported weights across most survey cycles (Figure 2). Men’s mean self-reported weights in NHIS were 1.4 kg lower and in BRFSS were 0.3 kg lower than NHANES self-reported weights (Figure 2).

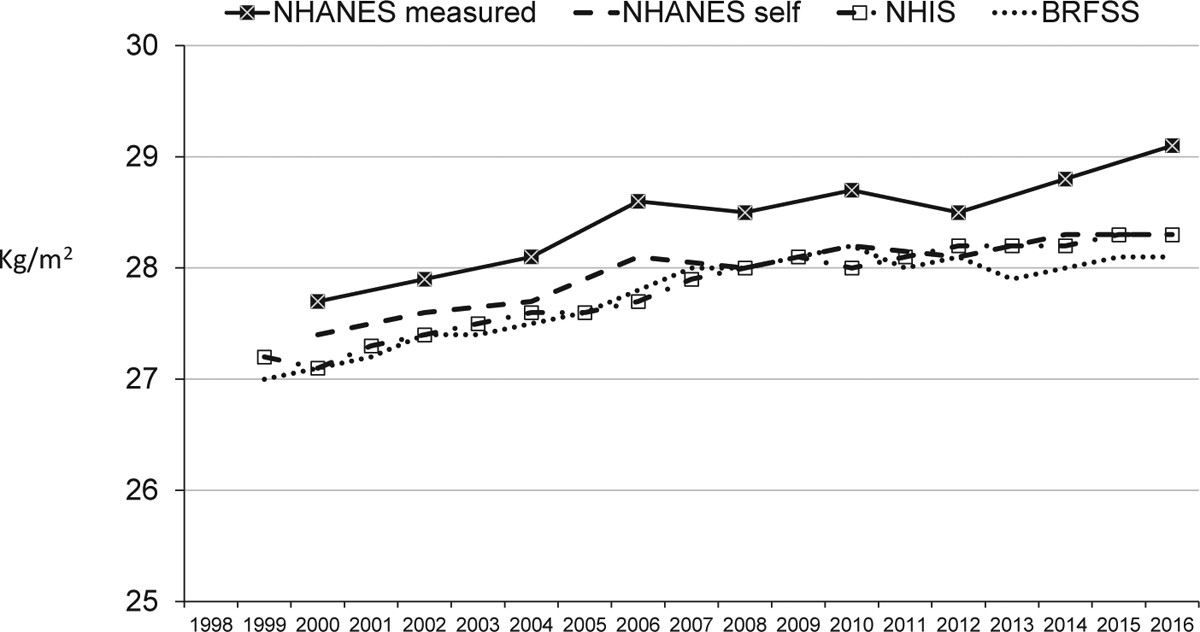

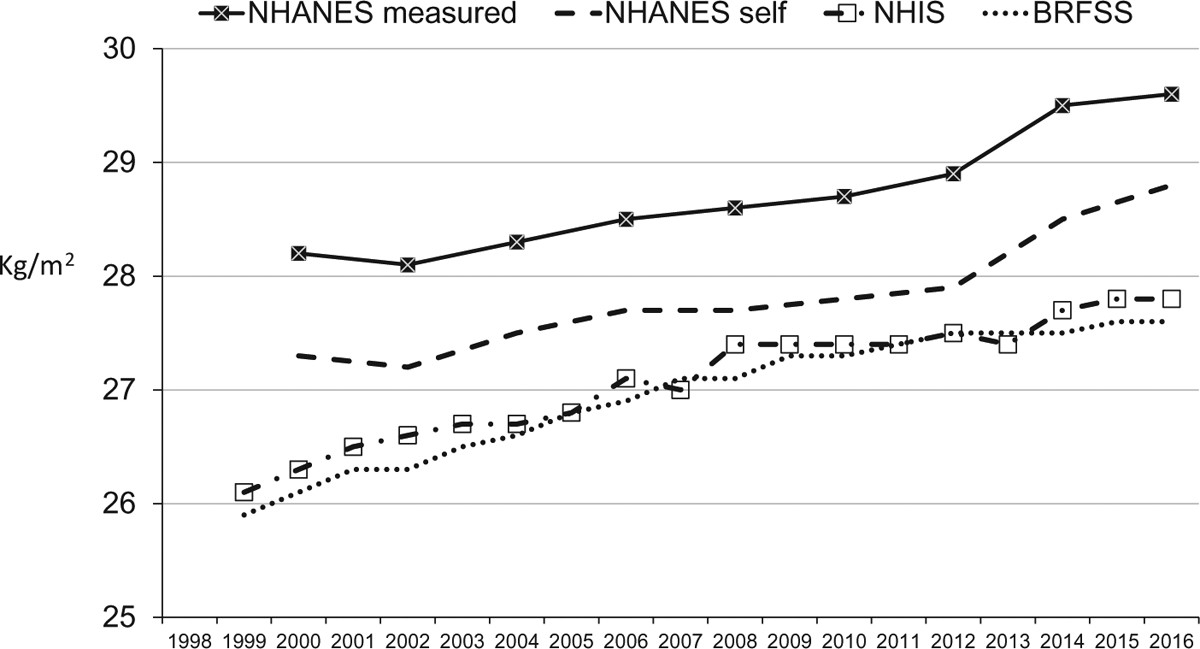

BMI Comparison

Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate that for both men and women, and across all survey cycles, mean BMI calculated from self-reported height and weight was lower than mean BMI calculated from measured values in NHANES. For men, mean BMI values from BRFSS and NHIS were both approximately 0.2 units lower than NHANES self-reported BMI. For women, these differences were larger, with NHIS BMI 0.7 units lower and BRFSS BMI 0.8 units lower than NHANES self-reported BMI.

Figure 3.

Mean BMI by survey for men, 1999 through 2016.

Figure 4.

Mean BMI by survey for women, 1999 through 2016.

Table 1 presents BMI, weight, and height distributions across the surveys. BMI distributions derived from self-reported data were narrower compared to measured BMI, particularly at higher percentiles. Median BMI values were lower for self-reported data compared to measured data for both sexes and were lowest for self-reported data from NHIS and BRFSS. This indicates a compression of the entire BMI distribution for self-reported data, most pronounced in NHIS and BRFSS. Height interquartile ranges (IQR) were similar across data types, slightly higher for self-reported data. Weight distributions were slightly compressed for self-reported data, with women showing considerably lower highest weight percentiles in self-reported data compared to measured data.

TABLE 1.

Selected percentiles and IQR of BMI, weight, and height by sex and survey: NHANES, NHIS, and BRFSS, 1999–2016

| Percentile/IQR | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | ||||||||

| Male | ||||||||

| NHANES measured | 20.6 | 22.0 | 24.5 | 27.6 | 31.3 | 35.6 | 39.1 | 6.8 |

| NHANES self-report | 20.8 | 22.1 | 24.3 | 27.1 | 30.7 | 34.6 | 37.8 | 6.4 |

| NHIS | 20.9 | 22.2 | 24.3 | 27.0 | 30.4 | 34.5 | 37.6 | 6.1 |

| BRFSS | 20.9 | 22.2 | 24.3 | 27.0 | 30.2 | 34.2 | 37.2 | 5.9 |

| Female | ||||||||

| NHANES measured | 19.5 | 20.8 | 23.3 | 27.3 | 32.6 | 38.5 | 42.5 | 9.3 |

| NHANES self-report | 19.4 | 20.4 | 22.8 | 26.5 | 31.5 | 37.1 | 41.0 | 8.7 |

| NHIS | 19.2 | 20.2 | 22.4 | 25.7 | 30.3 | 35.7 | 39.8 | 7.9 |

| BRFSS | 19.3 | 20.3 | 22.4 | 25.7 | 30.0 | 35.2 | 39.1 | 7.6 |

| Weight (kg) | ||||||||

| Male | ||||||||

| NHANES measured | 61.6 | 66.2 | 74.8 | 85.3 | 98.6 | 112.9 | 124.0 | 23.8 |

| NHANES self-report | 63.1 | 67.6 | 74.8 | 85.0 | 98.1 | 112.1 | 122.3 | 23.3 |

| NHIS | 64.3 | 67.9 | 75.4 | 83.9 | 95.2 | 108.6 | 115.5 | 19.8 |

| BRFSS | 63.5 | 68.0 | 75.0 | 84.9 | 97.4 | 111.2 | 122.3 | 22.4 |

| Female | ||||||||

| NHANES measured | 50.2 | 53.8 | 61.0 | 71.4 | 85.7 | 102.5 | 114.4 | 24.7 |

| NHANES self-report | 49.8 | 53.4 | 59.9 | 69.9 | 82.8 | 99.6 | 111.0 | 22.9 |

| NHIS | 50.1 | 54.0 | 58.9 | 67.8 | 79.5 | 91.9 | 101.8 | 20.6 |

| BRFSS | 49.9 | 53.6 | 59.1 | 68.1 | 81.3 | 93.6 | 104.5 | 22.2 |

| Height (cm) | ||||||||

| Male | ||||||||

| NHANES measured | 163.3 | 166.2 | 170.8 | 176.0 | 181.0 | 185.5 | 188.2 | 10.2 |

| NHANES self-report | 162.9 | 165.9 | 170.7 | 176.4 | 181.6 | 186.2 | 188.8 | 10.9 |

| NHIS | 164.1 | 166.5 | 171.1 | 176.5 | 181.4 | 185.6 | 187.8 | 10.3 |

| BRFSS | 163.3 | 166.2 | 171.2 | 176.8 | 181.9 | 186.5 | 189.3 | 10.7 |

| Female | ||||||||

| NHANES measured | 150.4 | 153.0 | 157.2 | 162.0 | 166.6 | 170.7 | 173.3 | 9.4 |

| NHANES self-report | 150.2 | 152.4 | 156.6 | 161.5 | 166.5 | 170.8 | 173.6 | 9.9 |

| NHIS | 151.0 | 153.1 | 156.9 | 161.5 | 166.4 | 170.3 | 172.6 | 9.5 |

| BRFSS | 150.6 | 152.7 | 156.9 | 161.7 | 166.7 | 171.1 | 174.0 | 9.8 |

IQR calculated as difference between 75th percentile and 25th percentile.

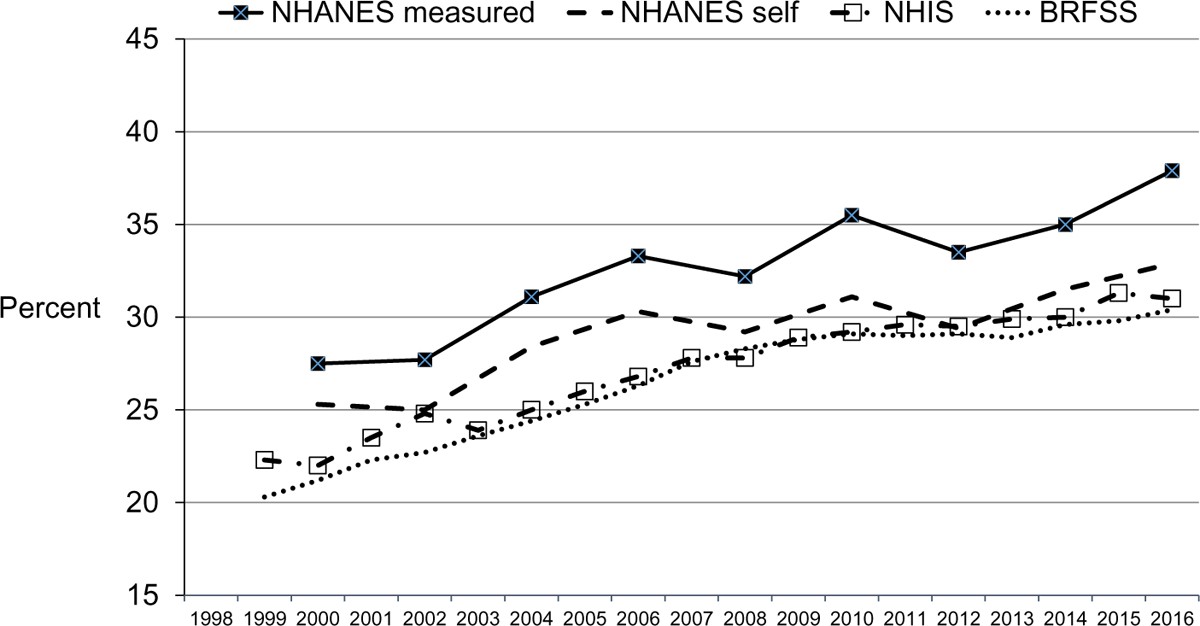

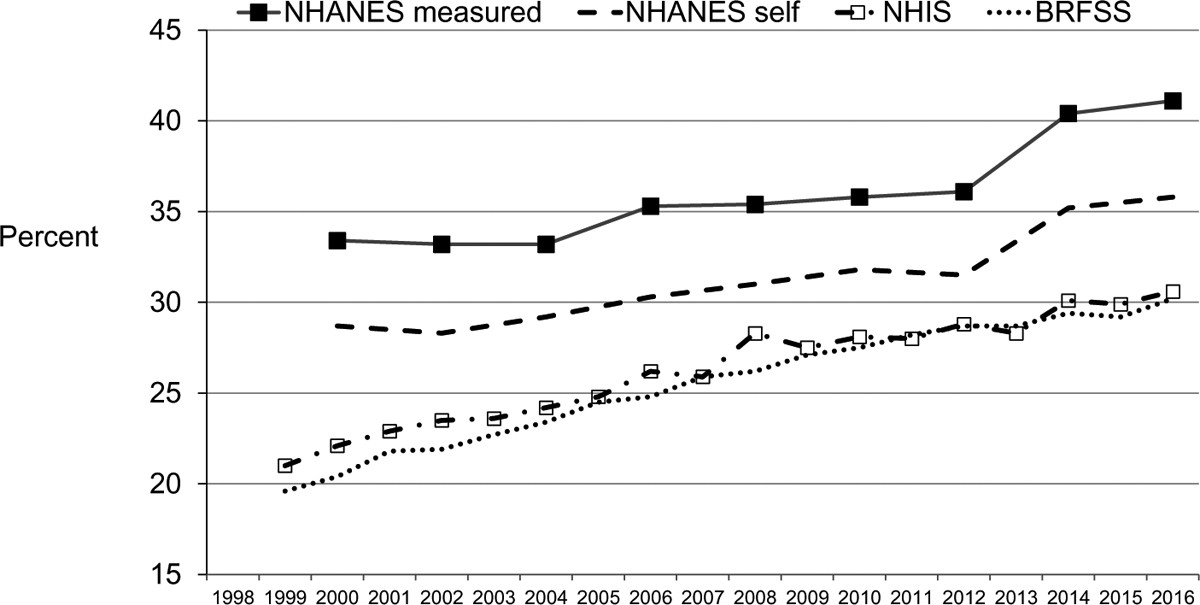

Obesity Prevalence Comparison

Obesity prevalence, defined as BMI ≥ 30, showed consistent underestimation when using self-reported data (Figures 5 and 6). For both men and women and across all survey cycles, obesity prevalence calculated from self-reported data was lower than prevalence based on measured NHANES data. For men, age-adjusted obesity prevalence using self-reported data was approximately 2.0 percentage points lower in NHIS and 2.7 percentage points lower in BRFSS compared to NHANES self-reported data. For women, these underestimations were more pronounced: 4.9 percentage points lower in NHIS and 5.7 percentage points lower in BRFSS.

Figure 5.

Age-adjusted obesity prevalence by survey for men, 1999 through 2016.

Figure 6.

Age-adjusted obesity prevalence by survey for women, 1999 through 2016.

Interestingly, the direction of sex differences in obesity prevalence varied by survey (Table 2). In NHANES (both measured and self-reported data), obesity prevalence was generally lower in men than women. The mean ratio of male to female obesity prevalence was 0.91 for measured and 0.93 for self-reported NHANES data. However, in NHIS and BRFSS, obesity prevalence was consistently higher in men than women, with mean ratios of 1.03 for NHIS and 1.04 for BRFSS.

TABLE 2.

Ratio of age-adjusted obesity prevalence among men to age-adjusted obesity prevalence among women by year and survey: NHANES, NHIS, and BRFSS, 1999–2016

| Survey year | NHANES measured | NHANES self-report | NHIS | BRFSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 1.06 | 1.04 | ||

| 2000 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 1.04 |

| 2001 | 1.03 | 1.02 | ||

| 2002 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 1.06 | 1.04 |

| 2003 | 1.01 | 1.04 | ||

| 2004 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 1.04 |

| 2005 | 1.05 | 1.03 | ||

| 2006 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.06 |

| 2007 | 1.07 | 1.07 | ||

| 2008 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 1.08 |

| 2009 | 1.05 | 1.06 | ||

| 2010 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.06 |

| 2011 | 1.06 | 1.03 | ||

| 2012 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 1.02 | 1.01 |

| 2013 | 1.06 | 1.01 | ||

| 2014 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 1.01 |

| 2015 | 1.05 | 1.02 | ||

| 2016 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Total | 0.91 | 0.93 | 1.03 | 1.04 |

Supplemental NHANES Analysis Results

NHANES data revealed that both men and women consistently overreported height across all survey cycles (Supporting Information Table S3). The overall mean overestimation was 1.36 cm for men and 0.87 cm for women. Regression models indicated that age group, measured height, and survey cycle significantly predicted height overreporting for both sexes.

Women, on average, underreported weight in every NHANES cycle (Supporting Information Table S4), with a mean underestimation of 1.37 kg. Measured BMI category, but not age or survey cycle, was a significant predictor of weight underreporting in women. Men, on average, slightly underreported weight by 0.08 kg. For men, age group, measured BMI category, and survey cycle were all significant predictors of weight reporting differences. Men with BMI ≥ 30 underreported weight, while those with BMI < 30 tended to overreport.

BMI calculated from self-reported data was consistently lower than measured BMI for both sexes in NHANES (Supporting Information Table S5). Age group, measured BMI category, and survey cycle were significant predictors of BMI difference for men, while age group and measured BMI category were significant for women.

Obesity prevalence from self-reported data was lower than that from measured data in NHANES for both men and women (Supporting Information Table S6). Age group was the only significant predictor of this difference for women. Survey cycle was not a significant predictor for either sex. Age-adjusted obesity prevalence from self-reported NHANES data was 3.11 percentage points lower for men and 4.2 percentage points lower for women compared to measured data.

Discussion

This study compared height, weight, BMI, and obesity prevalence across three major US national surveys, highlighting discrepancies between self-reported and measured data. Our findings on height and weight misreporting align with previous research [1, 2]. Both men and women in NHANES overreported height, with consistent self-reported heights across NHANES, NHIS, and BRFSS. Women exhibited greater weight underreporting than men, and self-reported weights were lower in NHIS and BRFSS compared to NHANES.

The relationship between misreported height/weight and BMI/obesity is complex. BMI errors reflect the combined effects of both height and weight reporting inaccuracies. These errors can either amplify or mitigate the overall BMI error. For instance, height overestimation reduces self-reported BMI, while weight overestimation increases it. Since height is in the BMI denominator, overreporting height leads to lower BMI values. The net impact on BMI depends on the magnitude and direction of reporting errors for both weight and height. Supporting Information Table S8 provides illustrative examples.

Obesity prevalence underestimation was more pronounced in women. While NHANES data showed lower obesity prevalence in men than women (both measured and self-reported), NHIS and BRFSS indicated the opposite. Yun et al. [27] reported similar gender, race, age, and education subgroup differences when comparing obesity prevalence between NHANES and BRFSS. This suggests limitations in using self-reported data for subgroup comparisons.

Secondary NHANES analyses revealed increasing height overreporting over time for both sexes, and increasing weight underreporting in men (specifically those with BMI > 30). However, these trends did not significantly alter the difference between self-reported and measured obesity prevalence over time.

Relying solely on mean values for comparison may not adequately address issues like obesity prevalence, which are sensitive to the entire distribution, not just averages. Even with seemingly good agreement in mean BMI, obesity prevalence can differ significantly between measured and reported values. Systematic errors in self-reported data can compress the BMI distribution. This can lead to misclassification into BMI categories and potentially bias hazard ratios in epidemiological studies [28]. Narrower BMI distributions from self-reported data can also artificially inflate hazard ratios, making associations appear stronger than they are [29].

While some studies have attempted to correct self-reported data using NHANES measured data [11, 12, 15, 17, 18, 30-32], the discrepancies between self-reported data across NHANES, NHIS, and BRFSS suggest that these corrections may be imperfect. The varying male-female obesity prevalence ratios across surveys further highlight this limitation. Furthermore, systematic errors in weight and height data make error correction using prediction equations challenging [33]. Our findings indicate that conclusions about NHIS and BRFSS self-reported data cannot be directly inferred from NHANES self-reported vs. measured data comparisons.

Several studies have compared self-reported height and weight data across NHANES, NHIS, and BRFSS. Li et al. [15] found similar obesity prevalence estimates across the three surveys using self-reported data, but did not consider measured NHANES data. Fahimi et al. [13] found no overall height differences across surveys in 2004 self-reported data, but significant differences for men specifically. For weight, they found significant overall differences and differences for women, but not men.

Differences in survey design, question wording, data editing, and mode of administration can contribute to inter-survey variations. NHANES participants were aware of subsequent physical measurements, which may improve self-reporting accuracy [12, 34-36]. Face-to-face interviews (NHANES, NHIS) may also yield more accurate data than telephone interviews (BRFSS) [12, 35, 37, 38]. However, our results suggest this isn’t always the case.

Conclusion

This study provides a detailed comparison of anthropometric data across NHANES, NHIS, and BRFSS, considering both self-reported and measured data. Patterns of height and weight reporting errors are complex and vary by age, sex, weight/height level, and survey type. The impact of misreporting on mean BMI depends on the direction and magnitude of errors for both height and weight. Secondary measures like BMI and obesity prevalence derived from self-reported data can exhibit unpredictable biases. Similar mean BMI values do not guarantee similar obesity prevalence. The overall effect of misreporting on obesity prevalence is influenced by population demographics and other factors associated with reporting biases. Therefore, understanding the complexities of height and weight misreporting is crucial for accurate interpretation of survey data and public health implications.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Tables

NIHMS1590171-supplement-Supplemental_Tables.pdf

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

[References will be added here if needed, following a standard citation format. For now, maintaining the original article’s reference links is sufficient for content integrity.]

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Tables