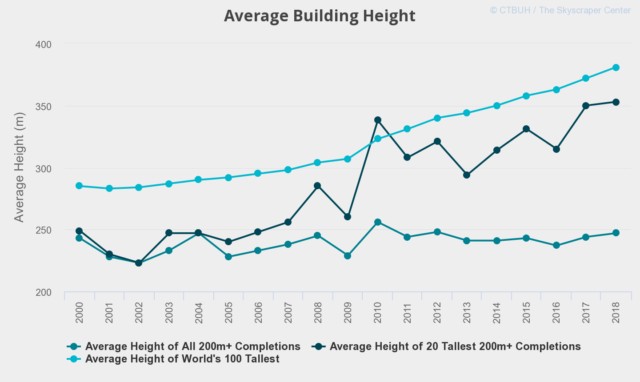

As we observe cityscapes globally, the increasing height of skyscrapers is undeniable. In 2000, the average height of the top 100 tallest buildings was approximately 285 meters (935 feet). By 2018, this average had risen to around 385 meters (1263 feet), reflecting an annual growth rate of 1.8%. What are the underlying factors driving this global ascent in building height?

The Role of Demand in Vertical Expansion

Skyscraper development is fundamentally driven by demand. These towering structures emerge to meet our need and desire for concentrated urban living and working spaces. As economies become increasingly service-oriented and reliant on intangible products, the pull towards urban centers intensifies. Key sectors such as finance, marketing, business services, and technology benefit significantly from clustering, fostering innovation and productivity. This economic dynamism, in turn, fuels the growth of consumer-centric urban environments, complete with cultural and entertainment amenities. The collective pursuit of enhanced opportunities draws populations to shared locations, and skyscrapers emerge as a solution – efficiently transforming air space into valuable land.

The Supply Side of Skyscraper Economics

However, a complete understanding of skyscraper heights requires examining not just demand, but also the forces governing their supply. To comprehend global building patterns, particularly in rapidly developing regions like China and the United Arab Emirates, we must analyze construction costs in these locations. The burgeoning skylines in Asia are as much a product of cost-effective construction as they are of urbanization and the growing prominence of global cities.

Source: CTBUH (2018).

The Economic Theory Defining Optimal Skyscraper Height

Before delving into the intricacies of skyscraper construction costs, it’s essential to consider the economic theory that dictates skyscraper height. The economic height of a building represents the optimal balance between the demand for height and the costs associated with achieving it. Economic modeling reveals a simplified equation for this optimal height:

Economic Height = (Market Price Per Floor) / (Construction Costs Index Value)

In simpler terms:

H = P / C

Here, H represents economic height, P denotes the market price per floor, and C signifies a construction costs index, encompassing material and labor prices, as well as construction efficiency. This equation illustrates that, assuming all other factors remain constant, a lower C value will result in taller buildings in a given city at a specific time.

Deconstructing “P”: Market Price and Land Value

To understand the consistent pattern of tall buildings concentrated in city centers and lower-rise structures in suburban areas, we must examine market prices per floor (or per square meter). These prices typically decrease sharply as distance from the city center increases. Within a city at a given time, construction costs (C) can be assumed relatively uniform for all developers. Therefore, variations in P reflect what occupants are willing to pay for space in different locations.

The market price per floor, P, can be broadly divided into two components: the quality of the building itself (e.g., elevator speed, views, finishes) and the quality of its location. Location is the primary driver of skyscraper height in central areas, where land value is exceptionally high. Businesses in central business districts, like Wall Street firms, are willing to pay a premium to cluster together and maximize profits. Developers respond to this high willingness to pay by building vertically. Conversely, the willingness to pay, and consequently land prices per square meter, diminishes rapidly as one moves away from the urban core. This phenomenon is well-documented globally and historically.

3D Visualizations of Land Values in Chicago. Each of these graphs shows the relative value of land in Chicago at different points in time. The peak is in the Loop and falls steeply from there. Source: Ahlfeldt and McMillen (2014).

The Dynamic Interplay of Price and Cost

Skyscraper height is thus a product of the ratio between benefits and costs. While location-based prices can serve as a reasonable indicator of optimal building height within a city at a given time, comparing economic height across time or between cities introduces complexities. Both P and C become variable.

Consider New York City and Shanghai. Despite similar average heights for skyscrapers completed since 1988, the underlying price-to-cost dynamics differ significantly. In New York, both prices and costs are elevated compared to Shanghai, yet their ratio results in comparable building heights. Asking rents in New York’s One Vanderbilt tower near Grand Central Station reach up to $160 per square foot (approximately $1722 per square meter). In contrast, Shanghai Tower, a taller structure, has reportedly commanded asking rents at roughly half that amount. This disparity offers insights into the relative construction costs in these two global cities, despite yielding similar average skyscraper heights. This difference in land prices per square meter significantly contributes to the overall price variations.

The Roaring Twenties and Building Booms

This economic framework also sheds light on historical building booms, such as that experienced in New York during the Roaring Twenties. During this period, rising P values, driven by economic growth, coincided with decreasing C values due to technological advancements and learning curve efficiencies in construction. This confluence of increasing market prices and decreasing costs facilitated a rapid surge in skyscraper heights.

The Average Heights of Completed Skyscrapers in New York and Shanghai, 1988-2017. Here a skyscraper is a building of at least 150 meters. Source: The Skyscraper Center, CTBUH.

Global Construction Costs: A Comparative Perspective

Labor costs are a major determinant of global construction costs. For instance, an unskilled construction worker in New York earns approximately $17.57 per hour, while in India, the wage is around $0.63 per hour, and in China, about $3.36 per hour. Given that labor can constitute a substantial portion of total construction expenses (potentially half in the U.S.), lower labor costs directly translate to reduced overall costs, encouraging developers to build taller.

Comparing specific projects further illustrates this point. One World Trade Center in New York cost nearly $4 billion, whereas the taller Shanghai Tower cost $2.4 billion. On a per-floor basis, New York’s costs were almost double. The Burj Khalifa, significantly taller than One World Trade Center, was constructed for 61% less. The notion of building a 163-story structure in New York for $1.5 billion is practically inconceivable, highlighting the dramatic cost differences.

Construction Costs for Some Supertall Skyscrapers Around the World. Source: Emporis.

Developing a Skyscraper Cost Index

To analyze these cost variations systematically, a skyscraper construction cost index was created, utilizing data from Emporis.com, which lists costs for 200 large high-rise buildings. (Detailed methodology is available here). This index, while a preliminary measure, reveals that mainland China and Arabian countries achieve substantial discounts on skyscraper construction compared to the United States, and especially New York City.

A Skyscraper Construction Cost Index. Underlying data is from Emporis. Index details are in Barr and Luo (2017).

“Costnomics”: Understanding Cost Behavior with Height

While a cost index provides average construction cost comparisons, a deeper understanding requires examining how total costs change with building height. From a developer’s perspective, maximizing profit involves determining how total costs evolve as height increases, to identify the optimal height.

Generally, average costs per square meter are believed to follow a U-shaped curve relative to building height. For shorter buildings, increasing height reduces per-floor costs. However, beyond a certain point, these costs begin to rise. The cost of adding the 51st floor exceeds that of the 41st. The exact inflection point remains debated and appears to vary across cities.

Economic theory dictates that a profit-maximizing developer will continue adding floors until the revenue from the last floor equals its cost. Building shorter than this optimal height leaves potential profit unrealized, while exceeding it results in losses as the cost of the additional floor surpasses its revenue.

The Escalating Costs of Verticality

The increasing costs associated with greater height beyond a certain point stem from the inherent challenges of tall building construction. Taller structures require progressively thicker and stronger materials, like concrete and steel, especially in lower floors, to support the immense superstructure, including essential internal systems like plumbing and electrical infrastructure. Foundation costs also rise with building height to bear the increasing weight.

Mitigating Wind Forces

Wind bracing adds further complexity and cost. Tall buildings are continuously subjected to wind pressure, which intensifies with height, increasing sway. To ensure occupant comfort and safety, additional structural materials are needed to enhance rigidity and minimize perceptible movement. Modern supertall buildings often employ sophisticated solutions like massive pendulums to dampen sway to imperceptible levels rather than aiming for absolute rigidity.

The Elevator Efficiency Challenge

Elevator systems present another height-related cost challenge. As buildings ascend, the need for additional elevator shafts and more elevators increases to maintain efficient vertical transportation. Developers must carefully weigh the trade-off between lost rentable space and added costs against the increased revenue from additional height. Generally, taller buildings necessitate more extensive elevator infrastructure.

Empirical Evidence: Costs Across Three Cities

To examine these cost dynamics, data was gathered for recently constructed buildings in New York, Chicago, and Shanghai (methodology details here). This dataset includes total construction costs and floor counts for each building, allowing for analysis of average per-floor cost variations with height. This approach provides insights into the economics of skyscraper height. However, it’s important to acknowledge the small sample sizes and diverse building types within each city, ranging from public housing in Shanghai to supertall offices and luxury apartments. The per-floor cost analysis presented here is preliminary and does not control for these variables.

Cost Comparisons: New York, Chicago, and Shanghai

Initial analysis reveals significantly lower construction costs in Shanghai and Chicago compared to New York City. The average per-floor cost in Chicago is approximately $6.2 million, and in Shanghai, around $3.7 million. In New York, the average is about $15 million per floor. For instance, a $20 million per-floor investment could yield a 65-story skyscraper in New York, a 120-story building in Shanghai, or a 100-story structure in Chicago.

Furthermore, the height at which per-floor costs reach their minimum varies across these cities. In New York, the lowest per-floor costs occur around 32 stories, and in Chicago, at approximately 55 stories. Shanghai, based on available data, does not exhibit a clear turning point, with per-floor costs appearing to rise consistently with height. Further investigation is needed to fully understand these city-specific cost behaviors.

Skyscraper Costs versus Building Height for New York, Chicago, and Shanghai. Costs are given in millions of 2018USD. Each dot is data for a particular building. The curves are trend lines (polynomial of order 2). Sources: see here.

The Future Trajectory of Skyscraper Height

The trend towards increasing skyscraper heights is poised to continue. While symbolic milestones like the first one-kilometer or one-mile high tower capture public imagination, their eventual realization is contingent upon sustained economic growth, which will continue to inflate the value of prime urban locations globally, and ongoing technological innovation that reduces the cost of building at height.

The rapid emergence of countries like the U.A.E., Saudi Arabia, and China in the skyscraper race is facilitated by their access to a global ecosystem of skyscraper expertise – architects, engineers, financial institutions, and specialized suppliers. This network accelerates the dissemination of knowledge and best practices to developing nations seeking to expand their urban centers vertically. The experience gained in these regions, in turn, enriches the global knowledge base, further accelerating technological progress and reducing construction costs worldwide. However, cities like New York City face challenges in maintaining global leadership in skyscraper height due to rapidly escalating construction costs, which can negate the benefits of technological advancements.

Ever Upwards: The Unstoppable Ascent

The pace and direction of technological change in skyscraper construction are complex to quantify, but will be explored in future discussions. However, the underlying economic forces and human ambition driving the desire to build taller ensure that humankind will continue to find innovative ways to reach new heights. The economics of skyscraper height firmly supports this upward trajectory.

Continue reading. The rest of the series can be read here.

[1] Prices are typically expressed in dollars per square foot or meter. For this analysis, per-floor costs are used to illustrate the economic principles. For simplicity, assume a standardized floor size of 200’ x 100’ = 20,000 square feet (approximately 1858 square meters), representing a typical floor area for a modern high-rise in the U.S.