INTRODUCTION

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder stemming from the loss of function of paternally expressed genes within the 15q11–q13 region of chromosome 15. This genetic anomaly leads to a range of characteristic features, including severe hypotonia at birth, feeding difficulties in infancy, hypogonadism, distinctive small hands and feet, developmental delays, behavioral challenges, and genital hypoplasia. A hallmark of PWS emerges between two and four years of age: an insatiable appetite that, if unchecked, can lead to severe obesity [Cassidy et al., 1997; Butler and Thompson, 2000; Bittel and Butler, 2005].

The genetic underpinnings of PWS are diverse. In approximately 70% of cases, the syndrome is attributed to a paternal deletion within the 15q11–q13 region. Around 25% of individuals with PWS exhibit uniparental maternal disomy 15 (UPD), where both copies of chromosome 15 are inherited from the mother. The remaining 2–5% of cases involve imprinting defects or chromosomal translocations [Nicholls and Knepper, 2001; Bittel and Butler, 2005]. Within the deletion subtype, a critical area of investigation is the proximal breakpoint region on 15q11–q13. Research indicates that these breakpoints often occur at one of two specific sites, located within large duplicated sequences centromeric to the ZNF127 locus [Pujana et al., 2001; Chai et al., 2003]. This observation has led to the categorization of PWS deletions into two primary subgroups [Knoll et al., 1990; Amos-Landgraf et al., 1999; Butler et al., 2004; Bittel and Butler, 2005]. Type I (TI) deletions, the larger of the two, involve breakpoint 1 (BP1), located closer to the centromere and proximal to the microsatellite marker D15S1035. Type II (TII) deletions, smaller in size, involve breakpoint 2 (BP2), situated near BP1 but distal to D15S1035. Breakpoint 3 (BP3), common to both deletion types, is found at the telomeric end of the 15q11–q13 region, distal to the OCA2 gene.

While early studies in the 1990s provided approximate locations for these breakpoints, advancements in genomic technologies now enable much finer mapping. Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH), particularly array-based CGH (aCGH), has emerged as a powerful tool in this endeavor. Commercially available whole-genome microarrays used in aCGH offer resolutions exceeding 10 kb, significantly enhancing breakpoint localization precision. Furthermore, the growing interest in copy number variation (CNV) across the human genome has revealed an unexpectedly high degree of genetic variability in terms of gene copy number. This variability has profound implications for both genetic diversity and susceptibility to human diseases [Barrett et al., 2004; Conrad et al., 2006; Fiegler et al., 2006; Khaja et al., 2006; Komura et al., 2006; Perry et al., 2006; Redon et al., 2006; Sebat et al., 2007; Stranger et al., 2007].

In light of these technological advancements and the evolving understanding of CNVs, we conducted a detailed evaluation of 25 individuals with PWS resulting from typical deletions. Our study employed high-resolution aCGH to achieve a more precise mapping of breakpoints within the 15q11–q13 region and to explore CNVs throughout the rest of the genome. By utilizing comparative genomic hybridization, we aimed to gain deeper insights into the genomic architecture of PWS deletions and the broader landscape of copy number variation in affected individuals.

UNDERSTANDING COMPARATIVE GENOMIC HYBRIDIZATION (CGH)

Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) is a molecular cytogenetic technique used to detect copy number variations (CNVs) across the genome. It allows for the comparison of DNA copy number between a test sample and a reference sample, identifying regions of chromosomal gains or losses in the test sample relative to the reference.

In array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), DNA from the patient (test DNA) and a control sample (reference DNA) are differentially labeled with fluorescent dyes (typically red and green). These labeled DNA samples are then hybridized to a microarray slide containing thousands of DNA probes spotted in an ordered grid. These probes represent specific locations across the genome.

After hybridization and washing, the microarray is scanned to measure the fluorescence intensity of each dye at each probe location. The ratio of the fluorescence intensities (test/reference) provides a measure of the relative copy number of DNA sequences in the test sample compared to the reference sample.

- Normal copy number: A ratio of approximately 1:1 (equal amounts of test and reference DNA hybridized to the probe) indicates a normal copy number in the test sample.

- Deletion: A reduced ratio (less test DNA than reference DNA hybridized) indicates a deletion in the test sample at that genomic location.

- Duplication: An increased ratio (more test DNA than reference DNA hybridized) indicates a duplication in the test sample at that genomic location.

High-resolution aCGH, utilizing microarrays with a high density of probes spaced closely across the genome, offers significant advantages for precise genomic analysis. This enhanced resolution allows for:

- Accurate detection of small CNVs: Identifying even small deletions and duplications that might be missed by traditional cytogenetic methods or lower-resolution CGH techniques.

- Precise breakpoint mapping: Determining the exact genomic coordinates of deletion or duplication breakpoints, crucial for understanding the mechanisms of chromosomal rearrangements and their impact on gene function.

- Genome-wide CNV profiling: Simultaneously screening the entire genome for CNVs, providing a comprehensive view of genomic imbalances in a single experiment.

In the context of Prader-Willi syndrome, comparative genomic hybridization, particularly high-resolution aCGH, is invaluable for characterizing the 15q11–q13 deletions, mapping breakpoints with greater accuracy, and investigating the broader landscape of CNVs that may contribute to the phenotypic variability observed in individuals with PWS.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

Our study cohort included 25 individuals diagnosed with Prader-Willi syndrome. Twelve of these subjects were classified as having type I (TI) deletions (5 males, 7 females; mean age 24.7 ± 9.5 years), and 13 were classified as having type II (TII) deletions (4 males, 9 females; mean age 18.6 ± 6.1 years). The diagnosis of PWS was rigorously confirmed for each participant through DNA methylation testing. Deletion status was determined via cytogenetic analysis, encompassing fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with the SNRPN probe, and genotyping of informative microsatellite markers such as D15S1035, which is located between breakpoints BP1 and BP2. The paternal origin of the deletion and the specific deletion subtype (TI or TII) were established using previously described methodologies [Butler et al., 2004].

Methods

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using a Gentra DNA isolation kit (Gentra, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. All comparative genomic hybridization analyses were performed using Agilent 244K whole human genome microarrays (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). These high-resolution microarrays feature an average probe spacing of 6.4 kb across the genome. Sex-matched comparison genomic DNA was obtained commercially from Promega (Madison, WI). Detailed protocols for genomic DNA preparation, labeling, hybridization, and scanning are available at http://www.home.agilent.com. Hybridization and initial data analysis were conducted commercially at Cogenics Inc. (Morrisville, NC).

Copy number variants (CNVs) were identified using CGH Analytics software with the Aberration Detection Method 2 (ADM-2) analysis algorithm (Agilent Technologies). ADM-2 is a quality-weighted interval score algorithm designed to detect aberrant intervals, such as CNVs, based on the statistical significance of consistently high or low log ratios. The algorithm iteratively identifies genomic intervals exceeding a user-defined statistical threshold (in this study, a minimum score of 12 and an aberration filter setting of 20). The ADM-2 score reflects the deviation of the weighted average of normalized log ratios from an expected value of zero, incorporating quality metrics for each probe measurement.

A subset of fifteen PWS subjects underwent more extensive CNV analysis beyond the 15q11–q13 region. CNVs were included in our study only if they met the same stringent statistical threshold. Several CNVs identified outside the Prader-Willi critical region (e.g., on chromosomes 3q and 8p) were validated using quantitative PCR. Primers specific to the regions of interest (deleted or duplicated) were designed, and quantitative PCR was performed using a hot-start PCR mix containing SYBR green (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) on an ABI 7000 thermocycler, as previously described [Bittel et al., 2006, 2007b]. Five replicates were run for each sample. Dissociation analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis were used to confirm the amplification of single fragments of the expected size. Furthermore, initial PCR products were sequenced and subjected to BLAST analysis against the human genome to verify the correct product amplification. CNV findings were compared to publicly available data on human genome variation [http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/].

RESULTS

We performed high-resolution aCGH analysis on 25 PWS subjects (12 with type I deletions and 13 with type II deletions) using 244K microarrays. The probe resolution in the 15q11–q13 region was approximately 14.5 kb, enabling more precise breakpoint identification compared to previous studies of typical PWS deletions.

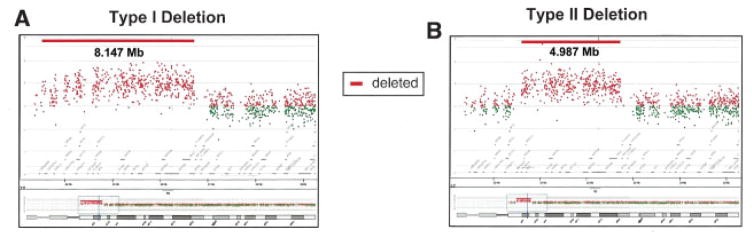

In individuals with type I deletions, breakpoint analysis revealed a range of BP1 locations near the centromere. Seven subjects had a BP1 at 20.220 Mb (measured from the p terminus); one at 20.080 Mb; two at 19.806 Mb; one at 18.722 Mb; and one at 18.683 Mb. The 244K microarray lacked probes closer to the centromere than 18.683 Mb and probes on the short arm of chromosome 15. Thus, 18.683 Mb may represent a minimal proximal boundary for BP1. The most distal BP1 breakpoint was 20.220 Mb. The BP1 region spanned 1.537 Mb in type I deletion subjects. Type I deletion sizes ranged from 5.721 to 8.147 Mb, averaging 6.583 Mb (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Typical type I and type II 15q deletion sizes and breakpoint assignments in Prader-Willi Syndrome, visualized through comparative genomic hybridization.

For type II deletions, breakpoints were distal to marker D15S1035, starting at nucleotide 20,459,962. BP2 breakpoints varied: two subjects at 21.357 Mb; one at 21.320 Mb; two at 21.236 Mb; four at 21.219 Mb; one at 21.208 Mb; one at 21.195 Mb; one at 20.851 Mb; and one at 20.812 Mb. The proximal-most BP2 was 20.812 Mb, and the distal-most was 21.357 Mb. BP2 region span was 0.545 Mb in type II deletion subjects. Type II deletion sizes ranged from 4.770 to 6.435 Mb, averaging 5.330 Mb (Fig. 1).

BP3 was common to both type I and type II deletions (Fig. 2). In type I deletions, BP3 locations were: 25.941, 25.979, 26.194 Mb (three subjects), 26.209, 26.365, 26.830 Mb (three subjects), 27.015, and 27.041 Mb (Fig. 3). In type II deletions, BP3 locations were: 26.127, 26.182, 26.209 Mb (six subjects), 26.830 Mb (two subjects), 27.112 Mb (two subjects), and 27.286 Mb. A 0.5 Mb gap in probe coverage on the 244K microarray (region 26.233–26.739 Mb) made BP3 determination less precise. However, two localized BP3 regions emerged: approximately 26.2 Mb and approximately 26.8 Mb. No correlation was found between deletion type and BP3 location. The BP3 region spanned 1.889 Mb overall (25.941 Mb to 27.286 Mb) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Representative comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) profiles of chromosome 15 in individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome, illustrating type I and type II deletions as detected by Agilent 244K CGH microarrays.

Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis of individuals with Prader-Willi syndrome, showcasing 15q11 duplications alongside typical 15q deletions. Data from Agilent 244K CGH microarrays depict regions of normal copy number, deletions, and duplications.

Intriguingly, aCGH identified 15q11 duplications in four of 25 PWS subjects (approximately 18.5 Mb to 20 Mb) (Fig. 3). One case was previously reported [Butler et al., 2002]. Duplication breakpoints were near the centromere, excluding the most proximal five to six array probes. This pattern mirrored observations in the largest type I deletions, suggesting a potential additional breakpoint site (?BP0) near the centromere, possibly due to duplicon-like sequences [Ji et al., 2000]. In two of four subjects with duplications, a non-deleted, non-duplicated region of approximately 0.5–1 Mb was observed between duplicated and deleted regions, corresponding to the BP1-BP2 interval (Fig. 3A).

Extensive CNV analysis beyond chromosome 15 in 15 PWS subjects revealed 47 CNVs (50 kb–1.6 Mb). Thirty CNVs (17 deletions, 13 duplications) were 50–300 kb, and 17 CNVs (11 deletions, 6 duplications) exceeded 300 kb. The smallest CNV was 60 kb, the largest 1.6 Mb. Average CNV size was 384 kb, with 3.1 CNVs per individual, and only one CNV per individual exceeding 300 kb on average. The most frequent CNVs were on chromosome 3 (approximately 164 Mb from p terminus; CNV_locus 0383) and chromosome 8 (approximately 39 Mb from p terminus; CNV_locus 1769) (Fig. 4), and were validated by quantitative PCR. These regions are known CNV sites in non-PWS populations [Perry et al., 2006; Redon et al., 2006] (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/).

Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Ideograms of human chromosomes illustrating copy number variation (CNV) regions (deletions and/or duplications) identified in high-resolution (244K) whole-genome comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis of Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) subjects. Deletions are on the left, duplications on the right. Numbers indicate CNV frequency in the PWS cohort. * Denotes 15q11 duplication in four PWS subjects, in addition to typical deletion.

The largest CNV (1.6 Mb deletion at Xp22) was observed in a PWS male, encompassing the steroid sulfatase gene (STS) and CNV_locus 0334 (a known CNV region). Previous whole-genome microarray expression analysis in this subject showed no STS expression in lymphoblastoid cells, while STS was readily detectable in other males without X deletions [Bittel et al., 2007b], consistent with the aCGH-detected deletion.

DISCUSSION

Previous estimations of deletion sizes in PWS were approximately 4 Mb for type I and 3.5 Mb for type II deletions. However, our high-resolution aCGH analysis indicates significantly larger deletion sizes, reaching 8.147 Mb, with an average of approximately 6.6 Mb for type I deletions. Subjects with the largest type I deletions (BP1 proximal to 20 Mb) lost at least three additional genes/transcripts (LOC283755, POTE5, OR4N4) beyond the four known genes between BP1 and BP2 (GCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA1, NIPA2). The clinical impact of these additional gene losses requires further investigation. Genotype-phenotype correlation studies are ongoing to assess the effects of varying deletion sizes and altered gene expression in the 15q11–q13 region. Type II deletions ranged from 4.770 Mb to 6.435 Mb.

The BP1 breakpoint frequently occurred at 20.220 Mb (7 of 12 type I subjects), suggesting a potential instability hotspot at this location. BP2 breakpoints were less localized around 21.22 Mb, possibly indicating a broader instability region or fewer repetitive sequences, aligning with prior observations of repeat structures in this region [Christian et al., 1999]. The wide span of BP3 locations may reflect the larger duplicon repeat region at the BP3 locus [Christian et al., 1999]. We observed a potential bimodal distribution of BP3 breakpoints, centered around 26.2 Mb and 27 Mb, consistent with prior reports of two distal breakpoints, BP3A and BP3B [Wang et al., 2004]. Recent Methylation-Specific Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) analysis of PWS genetic subtypes also supports a bimodal BP3 distribution relative to the APBA2 gene [Bittel et al., 2007a].

The advent of CNV analysis technologies has revealed a surprising degree of genomic variation in the human genome [Conrad et al., 2006; Khaja et al., 2006; Komura et al., 2006; Redon et al., 2006; Stranger et al., 2007]. CNV counts per genome range from a few to over 100, depending on size criteria, but their phenotypic consequences are still being elucidated. We observed an average of three CNVs per PWS individual. However, most CNVs (40 of 47) were in previously identified CNV regions without known clinical significance. Seven CNVs were located within or near gene families with multiple copies (e.g., HLA genes on 6p, olfactory receptor genes on 1q, 14q, and 15q), consistent with repeated sequence regions being prone to rearrangements [Giglio et al., 2001]. The average CNV size in our PWS cohort was 384 kb (range 60 kb–1.6 Mb), comparable to previous reports using oligonucleotide arrays (25 kb–3 Mb) [Sebat et al., 2004; Scherer et al., 2007]. A cluster of ADAM genes was observed at a frequently seen CNV site on chromosome 8p (CNV_locus 1769).

Our investigation into genotype-phenotype relationships in PWS using high-resolution CGH microarrays revealed that PWS subjects exhibit CNVs similar to those in the general population (e.g., 8p deletion/duplication). Notably, we identified a novel deletion within 15q14 and 15q11 duplications (approximately 1 Mb) in four subjects, co-occurring with the typical deletion. The 15q11 duplication was previously reported in one of these subjects and also found in unaffected family members [Butler et al., 2002]. Segmental 15q11 duplications are documented CNVs in the general population (Human Database of Genomic Variants: http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/?source=hg18). One subject had an Xp22 deletion encompassing STS and CNV_locus 0334. Lack of STS expression in this subject, confirmed by whole-genome expression microarray analysis [Bittel et al., 2007b], underscores the potential clinical relevance of CNVs and gene expression levels. Given the limited reported genomic structural differences in PWS, these genomic anomalies, along with type I vs. type II deletion size variations, warrant consideration in genotype-phenotype studies.

Our earlier work established a correlation between larger PWS deletion size and poorer clinical outcomes [Butler et al., 2004] and linked expression levels of genes between BP1 and BP2 to aberrant behavior [Bittel et al., 2006]. Our aCGH data demonstrate larger and more variable deletion sizes than previously recognized. Larger deletions inherently involve more genes/transcripts in the 15q11–q13 region. Therefore, a re-evaluation of genotype-phenotype correlations in our PWS cohort is justified based on these high-resolution aCGH findings.

Acknowledgments

Grant support was provided by NICHD PO1HD 30329, NICHD RO1HD 41672, the Hall Foundation of Kansas City, a Physician Scientist Award from Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics to M.G.B., and NIH grant 1U54 RR019478.

We extend our gratitude to the families and individuals who participated in this research.