Introduction

Morphine and oxycodone are potent opioid analgesics frequently used to manage moderate to severe pain. While both medications are effective for pain relief, clinical observations and experimental studies suggest they may exhibit different analgesic potencies, particularly in patients with sensitized pain systems, a condition often associated with chronic pain. Chronic pain, affecting millions worldwide, is frequently linked to hyperalgesia, an increased sensitivity to pain. This condition can be particularly challenging to treat, necessitating a deeper understanding of how different opioids perform in sensitized pain states. This article delves into a comprehensive comparison of morphine and oxycodone, drawing upon a robust experimental study that investigated their effects on experimentally induced hyperalgesia in healthy volunteers. By mimicking the sensitized pain system in a controlled setting, this research provides valuable insights into the differential analgesic capabilities of these two important opioids, bridging the gap between experimental findings and clinical pain management.

Background: Opioids and Sensitized Pain

Chronic pain is often characterized by hyperalgesia, a state of heightened pain sensitivity that can significantly complicate treatment. Opioids are a cornerstone of chronic pain management, yet the nuances of their effectiveness in inflammatory and sensitized pain conditions remain an area of active investigation. Inflammation, a key component of many chronic pain conditions, can trigger significant alterations within the pain pathways. These alterations can involve the upregulation of specific opioid receptors, potentially influencing how different opioids exert their analgesic effects.

Animal studies have indicated that inflammation can lead to an increased binding of opioids to κ-receptor sites, possibly due to an upregulation of these receptors in the nervous system. This is particularly relevant when considering morphine and oxycodone, as they are believed to possess distinct pharmacological profiles. Morphine is known for its strong affinity to the µ-opioid receptor, the primary target for most opioid analgesics. In contrast, preclinical studies in rodents suggest that oxycodone may act as a partial κ-agonist in addition to its µ-opioid receptor activity. These pharmacological differences could translate into varying analgesic potencies, especially in conditions where inflammation and hyperalgesia are present.

Experimental pain models are invaluable tools for dissecting the analgesic mechanisms of opioids. Crossover study designs, incorporating baseline pain measurements, offer a powerful approach to reveal subtle differences in drug effects. It’s crucial to assess pain responses across various tissues, as opioid analgesia can demonstrate tissue-specific variations. Furthermore, employing diverse pain modalities allows for a mechanistic exploration of how analgesics work at different levels of the pain pathway. Pain originating from deeper structures, such as muscle and viscera, is particularly relevant in opioid research because opioid analgesia tends to be more pronounced in deep pain.

Previous research comparing morphine and oxycodone in healthy volunteers using short-duration experimental pain stimuli found comparable analgesic potency for skin and muscle pain. However, oxycodone exhibited greater effectiveness against visceral pain. Interestingly, a study in patients with chronic pancreatitis, a condition marked by persistent inflammation and hyperalgesia, revealed that oxycodone was more potent than morphine in alleviating experimental pain across skin, muscle, and visceral tissues. This observation lends support to the hypothesis of differential analgesic potencies in the presence of hyperalgesia.

It is important to acknowledge that pain experienced in a laboratory setting by healthy volunteers differs from the complex and multifaceted nature of clinical pain. However, experimental hyperalgesia, a hallmark of clinical pain, can be reliably induced in healthy individuals. Sensitizing the esophagus with agents like capsaicin or acid can effectively mimic aspects of the sensitized pain system seen in chronic pain patients. Moreover, localized sensitization can even trigger generalized hyperalgesia, manifesting as heightened sensitivity in areas beyond the initially affected site. While experimental pain models with hyperalgesia present challenges in terms of control compared to simpler pain stimuli, they offer a more clinically relevant platform to investigate the analgesic effects of opioids in conditions that mirror inflammatory pain states.

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that an experimental human pain model incorporating hyperalgesia could effectively simulate the sensitized pain system observed in patients. The aim was to investigate whether morphine and oxycodone, compared to placebo, exhibit differential analgesic potencies in this hyperalgesic state and whether these differences vary across different tissue types. This research aimed to bridge the gap between experimental pain studies in healthy volunteers and clinical findings in pain patients.

Methods: Mimicking Sensitized Pain in Healthy Volunteers

This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the relevant authorities. It was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, ensuring rigorous monitoring and data integrity.

Participants and Study Design

The reliability and sensitivity of the experimental pain tests employed in this study have been previously validated. Based on prior research demonstrating the ability to detect analgesic differences between morphine and oxycodone with a sample size of 24, this study enrolled 24 opioid-naïve, healthy Caucasian volunteers (12 females, mean age 27.8 years). A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, three-way crossover design using a Latin square randomization was implemented. The study took place at a specialized research laboratory. All participants provided informed consent and were compensated for their time. Comprehensive medical screenings were conducted to ensure participant suitability, and female participants underwent pregnancy tests. To minimize variability and ensure reliable data collection, all volunteers underwent a training session to familiarize themselves with the pain stimulation procedures at least one week before the first study day. Participants fasted for at least 4 hours before each study session. Electrocardiogram monitoring was performed throughout each session for safety.

Upon arrival at the laboratory, baseline blood pressure and pulse measurements were taken. A multimodal esophageal probe, previously described in detail, was inserted transorally and positioned in the distal esophagus. Devices for skin and muscle pain stimulation were also positioned.

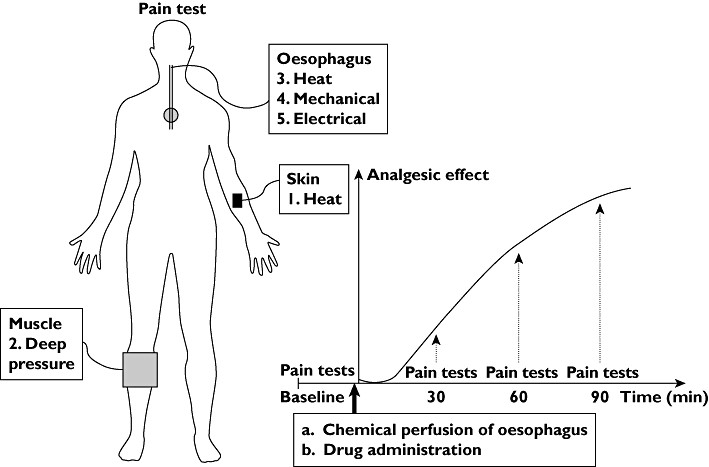

Figure 1: Study Protocol Flowchart. This diagram illustrates the sequence of pain tests (left) including skin heat, muscle pressure, and esophageal stimulations (heat, mechanical, electrical). The graph (right) depicts the study timeline: baseline pain tests, hyperalgesia induction, drug administration (placebo, morphine, or oxycodone), and pain tests at 30, 60, and 90 minutes post-drug.

Pain assessments were conducted at baseline, before any intervention, and then at 30, 60, and 90 minutes following hyperalgesia induction and drug administration. The order of pain stimulations (skin, muscle, esophageal) remained consistent across all testing sessions. This schedule was designed to capture drug effects during the absorption and early elimination phases, while avoiding excessively long testing periods. Participants were blinded to all measured thresholds. Adverse effects (nausea, dizziness, itching, sweating) were recorded using a four-point scale (none to intolerable) after each pain test battery. Sedation levels were assessed via a finger tapping test after each battery. In case of sedation or discomfort, blood pressure and pulse were re-evaluated. Participants were monitored post-study until any adverse effects subsided.

The experiment was repeated three times for each participant, with washout periods of at least one week between sessions to minimize carryover effects. Randomization aimed to balance out any time-dependent effects such as learning or order effects across the treatment groups.

Medications

Each participant received morphine (30 mg oral solution), oxycodone (15 mg oral solution), or placebo in randomized order across the three study periods. To maintain blinding, all treatments were masked with orange juice concentrate and diluted with water to a consistent volume and color. Medications were administered immediately after baseline pain recordings via a catheter within the esophageal probe, ensuring distal esophageal delivery. A pharmacist, not involved in other aspects of the study, prepared and dispensed the medications to maintain blinding for all investigators.

The morphine dose was twice that of oxycodone. This dose ratio was chosen because oxycodone has a higher oral bioavailability and faster onset of action compared to morphine, potentially leading to greater effects at equipotent doses. By using a higher morphine dose, the researchers aimed to ensure that any observed differences were not simply due to pharmacokinetic advantages of oxycodone. Furthermore, these doses had previously shown comparable analgesic effects in experimental skin and muscle pain models.

Pain Stimulation Methods

Skin Heat Stimulation

Cutaneous heat pain tolerance threshold (PTT) was assessed using a computer-controlled heat pain device. A thermode was applied to the forearm, and temperature increased at 1°C/s from a baseline of 32°C to a maximum of 52°C. Participants pressed a button to stop the stimulation when their pain tolerance threshold was reached. Three consecutive measurements were taken and averaged.

Muscle Pressure Stimulation

Muscle pain was induced using an electronic cuff algometer applied to the gastrocnemius muscle. The cuff pressure increased linearly at a rate of 0.50 kPa/s. Participants used a visual analog scale (VAS) to continuously rate pain intensity (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain imaginable). Pain detection threshold (PDT) was recorded at the first sensation of pain, and PTT was recorded when participants pressed a button to indicate their pain tolerance limit.

Esophageal Stimulation

For esophageal stimulation, participants used a 0-10 electronic VAS to rate visceral pain (0 = no perception, 5 = pain threshold (PDT), 10 = unbearable pain). They were instructed to differentiate between pain and general throat unpleasantness. Referred pain areas were mapped onto transparent paper over the pain location and later digitized for area calculation. Stimulations were terminated at moderate pain (VAS = 7) for mechanical and at PDT (VAS = 5) for thermal and electrical stimuli to prevent adverse autonomic reactions.

Mechanical Stimulation

Esophageal distension was achieved by inflating a bag at a constant rate of 15 ml/min until moderate pain (VAS = 7) was reached. The volume of distension at this pain level was recorded.

Thermal Stimulation

Heat stimuli were delivered by recirculating 60°C water through the esophageal bag, maintaining a constant volume to avoid mechanical distension. Temperature increased linearly at 1.5°C/min. PDT temperature was recorded.

Electrical Stimulation

Electrical stimulation was delivered via electrodes on the esophageal probe using a computer-controlled stimulator. A 25-ms train of five 1-ms square-wave impulses was delivered. Current intensity was increased in 1 mA increments until PDT was reached, and this intensity was recorded.

Hyperalgesia Induction

Hyperalgesia was induced by esophageal perfusion with a solution of acid (HCl 0.1 M) and capsaicin (1 mg in 10 ml solvent) at 7 ml/min. Perfusion continued until 100 ml was infused, or until the participant reached PDT (VAS = 5) and remained above this level for more than one minute, or it became intolerably unpleasant. This method has been previously validated to induce consistent hyperalgesia.

Statistical Analysis

To account for baseline pain variability, changes in stimulus intensity from baseline were used for statistical analysis. Results are presented as baseline-corrected means with 95% confidence intervals. Two-way ANOVA was used to assess overall effects of drug (placebo, morphine, oxycodone) and time (30, 60, 90 min). Significant overall effects were followed by post-hoc analyses using a generalized linear model. Total scores over 90 minutes were used in post-hoc drug effect comparisons. Friedman’s test was used for side effect comparisons. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results: Oxycodone Demonstrates Superior Analgesia in Sensitized Pain

All participants completed the study protocol. Esophageal perfusion with acid and capsaicin induced nausea and sweating in all volunteers, confirming successful hyperalgesia induction. Reported side effects for each treatment arm were mild and are detailed in the original article. There was no significant difference in the overall degree of side effects between morphine and oxycodone. Finger tapping frequency, an indicator of sedation, did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Skin Stimulation: Oxycodone More Effective Than Morphine

Compared to placebo, both opioids significantly increased heat pain tolerance threshold (PTT) (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that oxycodone was significantly more effective than both placebo (P < 0.001) and morphine (P= 0.016) in raising skin heat PTT. Morphine’s effect was not significantly different from placebo (P > 0.05).

Figure 2: Skin Heat Pain Tolerance. This graph shows skin heat pain tolerance thresholds (PTT) at baseline, 30, 60, and 90 minutes after drug administration (placebo, morphine 30mg, oxycodone 15mg). Oxycodone (black bars) resulted in significantly higher PTTs compared to placebo (white bars) and morphine (grey bars). Error bars represent SEM.

Muscle Stimulation: Oxycodone Superior to Morphine in Pain Tolerance

Both morphine and oxycodone showed a significant effect on muscle pain detection threshold (PDT) compared to placebo (P= 0.02). Post-hoc analysis showed both morphine (P= 0.03) and oxycodone (P= 0.012) were more effective than placebo at increasing PDT, with no significant difference between morphine and oxycodone.

For muscle pain tolerance threshold (PTT), there was a significant overall opioid effect (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis demonstrated that both morphine (P= 0.003) and oxycodone (P < 0.001) significantly increased muscle PTT compared to placebo. Crucially, oxycodone showed a significantly greater analgesic effect than morphine on muscle PTT (P < 0.001). There was also a significant time effect on muscle PTT (P= 0.016).

Figure 3: Muscle Pressure Pain Tolerance. This graph illustrates muscle pressure pain tolerance thresholds (PTT) at baseline, 30, 60, and 90 minutes after drug administration (placebo, morphine 30mg, oxycodone 15mg). Both morphine (grey bars) and oxycodone (black bars) increased PTT compared to placebo (white bars). Oxycodone showed a significantly greater effect than morphine. Error bars represent SEM.

Esophageal Stimulation: Oxycodone Shows Greater Analgesic Effect on Heat and Electrical Pain

Visceral stimulation induced both local and referred pain. Figure 4 illustrates the referred pain areas.

Figure 4: Referred Pain Areas in Esophageal Stimulation. This illustration shows the average referred pain areas reported during esophageal stimulations: (1) baseline, (2) after acid+capsaicin perfusion, (3) after morphine, (4) after oxycodone. Electrical stimulation (white) often resulted in smaller areas compared to mechanical (grey) or thermal (hatched) stimulation.

Mechanical Stimulation

No significant differences were found between drugs for tolerated esophageal distension volume or referred pain areas in response to mechanical stimulation.

Thermal Stimulation

While there was no significant opioid effect on temperature at pain detection threshold (PDT), the referred pain area in response to esophageal heat stimulation was significantly reduced by opioids (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed that oxycodone significantly reduced the referred pain area compared to both placebo (P < 0.001) and morphine (P < 0.001). Morphine’s effect on referred pain area was not significantly different from placebo (P= 0.056).

Figure 5: Esophageal Heat Stimulation – Referred Pain Area. This graph displays the referred pain areas corresponding to pain detection thresholds during esophageal heat stimulation at baseline, 30, 60, and 90 minutes after drug administration. Oxycodone (black bars) significantly reduced referred pain area compared to placebo (white bars) and morphine (grey bars). Error bars represent SEM.

Electrical Stimulation

Opioids had a significant effect on stimulation intensity at pain detection threshold (PDT) during esophageal electrical stimulation (P < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that oxycodone significantly increased the electrical stimulation intensity required to reach PDT compared to both placebo (P < 0.001) and morphine (P= 0.016). Morphine’s effect was not significantly different from placebo (P= 0.051). Referred pain areas in response to electrical stimulation were not significantly affected by drugs.

Figure 6: Esophageal Electrical Stimulation – Pain Detection Threshold. This graph presents pain detection thresholds (PDT) for esophageal electrical stimulation at baseline, 30, 60, and 90 minutes post-drug administration. Oxycodone (black bars) significantly increased PDT compared to placebo (white bars) and morphine (grey bars). Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion: Differential Analgesic Potencies in Sensitized Pain

This study compared the analgesic effects of morphine, oxycodone, and placebo in an experimental pain model involving induced hyperalgesia in healthy volunteers. The findings revealed differential analgesic potencies between morphine and oxycodone across various tissues under sensitized pain conditions. Specifically, oxycodone demonstrated superior analgesic effects compared to morphine in attenuating pain from heat stimulation of the skin, pressure stimulation of muscle, and heat and electrical stimulation of the esophagus.

Methodological Considerations

The study’s randomized crossover design effectively minimized period effects, ensuring balanced data across treatment arms. The robust experimental pain model, previously validated for reliability, allowed for consistent pain recordings. While sedation is a potential confounder in opioid studies, the intense pain stimulation paradigm likely counteracted sedation effects, as supported by the stable finger tapping frequency across groups.

The esophageal sensitization model using acid and capsaicin effectively induced hyperalgesia, as demonstrated in previous studies and confirmed by the increased pain sensitivity in the placebo arm. Experimentally induced hyperalgesia, particularly generalized hyperalgesia, is recognized as a translational bridge to clinical pain conditions, mimicking central nervous system sensitization seen in chronic pain.

The chosen doses and timing of pain assessments were based on pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic considerations, ensuring that measurements were taken during the active phase of both morphine and oxycodone. The use of a total score over 90 minutes for post-hoc analysis provides a clinically relevant measure of analgesic effect over time.

The higher dose of morphine was intentionally chosen to mitigate potential pharmacokinetic advantages of oxycodone. Despite this, oxycodone demonstrated superior analgesic effects in several endpoints, suggesting genuine pharmacodynamic differences. While there was a trend towards more side effects with oxycodone, no significant difference in overall adverse event profiles was observed. The esophageal perfusion-induced nausea and sweating likely helped to mask the inert placebo to some extent, enhancing blinding.

The use of multiple exploratory endpoints is acknowledged as a potential limitation regarding multiplicity. However, the two-way ANOVA and the focus on consistent findings across multiple pain modalities and tissues strengthens the overall interpretation and minimizes the risk of type 1 errors. The emphasis on pain from deeper structures, considered more clinically relevant, further prioritizes the most meaningful findings. The consistent results across skin, muscle, and esophageal pain modalities reinforce the robustness of the conclusions.

Different Effects of Morphine vs. Oxycodone

Skin

While skin heat stimulation may have limited clinical relevance due to its narrow dynamic range, the finding that oxycodone, but not morphine, significantly blocked induced generalized hyperalgesia in skin is noteworthy. This suggests a potentially different anti-hyperalgesic potency profile. The near-significant effect of morphine suggests that a larger sample size might reveal a statistically significant effect, but the clear superiority of oxycodone remains. The contrasting findings with a previous study showing equal potency in non-sensitized skin pain models highlight the importance of hyperalgesia in revealing these differential opioid effects.

Muscle

The observed increase in muscle pressure tolerance over time likely reflects habituation to tonic stimulation rather than sensitization in this modality. This may be due to the different spinal cord segments innervated by the gastrocnemius muscle compared to the esophagus and arm. Despite the lack of sensitization in muscle, both opioids showed analgesic effects, with oxycodone demonstrating superior efficacy in increasing pain tolerance. The differential effect primarily on PTT, rather than PDT, aligns with the understanding that opioids primarily affect pain intensity above the pain detection threshold. The consistency with findings in chronic pancreatitis patients, where oxycodone showed greater muscle pain relief, further strengthens the clinical relevance of these experimental results.

Esophagus

The lack of analgesic effect on esophageal heat pain detection threshold in this study, despite previous findings of oxycodone efficacy, might be attributed to the faster temperature change rate, potentially affecting pain assessment accuracy. However, the significant reduction in heat-evoked referred pain area with oxycodone, but not morphine, suggests a differential effect on central pain processing mechanisms altered by hyperalgesia. Similarly, while mechanical esophageal stimulation did not reveal drug differences, electrical stimulation, considered a more reliable visceral pain modality, demonstrated that oxycodone was more effective than both placebo and morphine in increasing pain detection threshold. This effect, bypassing peripheral nerves, points towards spinal and supraspinal mechanisms. The hyperalgesia-induced increase in referred pain area to electrical stimulation was also attenuated by opioids, although not significantly, possibly due to high inter-subject variability in reporting referred pain areas.

The sample size of 24, previously shown to be sufficient to detect morphine effects, may have been borderline for demonstrating morphine’s effect in this hyperalgesia model. The variability introduced by hyperalgesia might necessitate larger sample sizes to detect more subtle effects. However, the consistent demonstration of differential analgesic potencies between morphine and oxycodone across multiple tissues validates the study’s main outcome.

The observed differences could be linked to oxycodone’s potential interaction with a different population of opioid receptors or a subtly different modulation of µ-opioid receptor signaling in hyperalgesia. The hypothesis of κ-receptor involvement, potentially upregulated in inflammation and hyperalgesia, is supported by animal studies suggesting oxycodone’s partial κ-agonist activity. However, definitive confirmation in humans requires κ-selective antagonists suitable for clinical use.

Translational Pain Research and Clinical Implications

Human experimental pain models, particularly those incorporating hyperalgesia, serve as crucial translational tools bridging animal studies and clinical pain research. They offer advantages over animal models by directly assessing human pain perception and allow for controlled investigation of pain mechanisms, overcoming limitations of patient studies with confounding clinical factors. The consistency of the differential analgesic potencies observed in this study with previous findings in chronic visceral pain patients underscores the translational value of this experimental hyperalgesia model.

While the clinical significance of subtle analgesic potency differences is challenging to directly quantify in clinical practice, these experimental findings provide valuable support for clinical observations and the growing understanding of oxycodone’s distinct analgesic profile compared to morphine, especially in sensitized pain conditions. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of opioid pharmacology and may inform more tailored pain management strategies, particularly in chronic pain patients with hyperalgesia.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support from Norpharma (Mundipharma), the Research Initiative, Aarhus University Hospital, ‘Det Obelske Familie Fond’, and the Spar Nord Foundation.

Competing interests

C.S. reports employment by Grünenthal after study completion. No other competing interests declared.