Have you ever found yourself stuck trying to decide if a product idea is “good” or not? It’s a common challenge in product development. In my new book, Continuous Discovery Habits, I delve into structured approaches to product discovery, but today, I want to focus on a fundamental aspect of decision-making: compare and contrast. This concept is critical for product teams aiming to make strategic choices that truly resonate with users and drive business outcomes.

At Mind the Product London in 2017, I presented a tool called the Opportunity Solution Tree, designed to enhance critical thinking within product teams. The core of this tool is rooted in the power of comparative decision-making. Let’s explore why understanding “What Does It Mean By Compare And Contrast” is so vital in product development and how tools like the Opportunity Solution Tree can help us leverage it effectively.

To illustrate, let’s revisit a story I shared at Mind the Product. This story highlights a common pitfall: focusing on a single idea without considering alternatives, and how understanding the principle of compare and contrast could have led to a better outcome.

The Pitfall of “Whether or Not” Decisions

Back in 2008, I was a product manager at a startup focused on building online communities for university alumni associations. We faced a persistent problem: while alumni associations, our direct customers, loved the platform, alumni, the end-users, didn’t engage as much as we hoped. New communities would see an initial surge in activity, but engagement would quickly drop off.

User research revealed that alumni enjoyed sending messages within their community, seeking advice on everything from career transitions to moving to a new city. This was exactly the kind of interaction we aimed to foster.

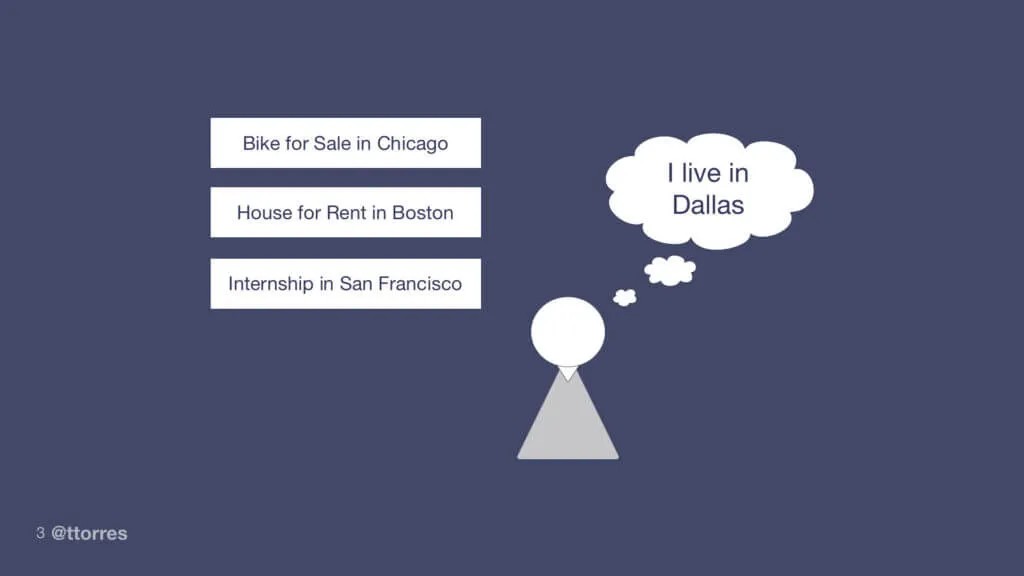

Illustration of irrelevant community messages received by alumni, highlighting the spam problem.

However, there was a major flaw: our system allowed users to easily spam entire alumni networks. Alumni in Dallas were receiving messages about apartments for rent in Boston or job opportunities in San Francisco. If we wanted to boost engagement, we had to address this issue of unwanted messages.

When I proposed brainstorming solutions to reduce spam, one of our engineers, Seth, suggested integrating Google Maps. His idea was to use the Google Maps API to display a map showing where alumni lived globally.

Humorous depiction of brainstorming, emphasizing the challenge of evaluating ideas.

I was perplexed. How would Google Maps solve the spam problem? When I asked Seth, he admitted it wouldn’t. His rationale was that it would be a “cool” feature and thus drive engagement. Surprisingly, the rest of the team agreed. They were excited about building something “cool.”

Intuitively, I felt uneasy. Building “cool stuff” didn’t seem like a robust strategy. Adding a Google Map felt like a gimmick, not a solution to our core problem. This experience highlighted a critical issue: we were making a “whether or not” decision about Seth’s idea. We were asking, “Is this Google Maps idea good?” instead of asking, “Compared to other potential solutions, is this the best way to increase engagement and reduce spam?”

This story isn’t about right or wrong ideas; it’s about the process of decision-making. As a product manager, I wanted team input, but I lacked a structured way to evaluate ideas effectively. This is a common struggle for product teams: moving from a desired outcome to impactful solutions. The problem often lies in how we approach idea evaluation and selection. We frequently fall into traps that hinder our ability to make the best choices.

Common Pitfalls in Product Decision-Making

Through my experience as a product discovery coach, I’ve observed recurring patterns that impede effective product decision-making. These often revolve around a lack of comparative analysis.

Falling in Love with First Ideas

It’s human nature to become attached to our initial ideas. When faced with a problem, our minds quickly generate potential solutions. This immediate solution generation can feel satisfying, leading us to prematurely embrace the first idea that comes to mind.

Visual emphasizing the tendency to become attached to initial ideas.

This is exactly what happened with Seth and the Google Maps idea. He was excited about a new technology and immediately envisioned an application for it. The team, in turn, got caught up in the excitement without critically evaluating its relevance to the core problem. When we fall in love with our ideas, we bypass the crucial step of questioning their merit and exploring alternatives. We fail to ask, “Compared to what else could we do, is this truly the best option?”

Not Considering Enough Ideas

Closely linked to falling in love with first ideas is the failure to generate and consider a sufficient range of options. When we fixate on an initial solution, we limit our exploration of the solution space.

Image highlighting the importance of considering multiple ideas for better outcomes.

Research on brainstorming consistently shows that generating a larger number of ideas leads to higher quality ideas overall. By limiting ourselves to a narrow set of solutions, we miss out on potentially better, more innovative approaches. In the context of “what does it mean by compare and contrast,” considering multiple ideas is essential because it sets the stage for comparative evaluation. It allows us to move beyond a simple “yes/no” decision about a single idea and instead engage in a “compare and contrast” exercise: “Which of these ideas is the most promising?”

The Google Maps idea, in isolation, might seem appealing. However, if we had generated a broader range of solutions to the spam problem and then compared them, the weaknesses of the Google Maps approach – its irrelevance to spam reduction – would have become much clearer.

Lack of Alignment on the Target Opportunity

Another common pitfall is failing to ensure the team is aligned on the problem or opportunity they are trying to address before jumping into solutions. In my story, Seth and I were not aligned on the core issue. I was focused on reducing spam, while Seth was thinking about increasing engagement through “cool” features, albeit tangentially related.

Visual depicting misalignment on the problem to be solved within a team.

Before generating solutions, it’s crucial to have a shared understanding of the target opportunity. This alignment ensures that everyone is working towards the same goal. Without it, teams might generate solutions that, while potentially “good” in isolation, are irrelevant to the actual problem they need to solve. In our case, Google Maps might have been a cool feature (a “good” idea in a vacuum), but it was misaligned with the opportunity of reducing spam to improve alumni engagement.

Rarely Considering Enough Opportunities

Just as we often don’t consider enough solutions, we also tend to limit ourselves to a narrow view of the opportunity space. Both Seth and I entered our brainstorming session with a pre-conceived notion of the primary opportunity. I was fixated on reducing spam, and Seth was focused on connecting local alumni. We were both operating within a limited frame of reference.

Image emphasizing the importance of comparing opportunities rather than evaluating a single one.

Similar to solution evaluation, we often approach opportunity assessment with a “whether or not” mindset: “Is reducing spam a worthwhile opportunity?” Instead, we should be asking: “Compared to other opportunities to increase alumni engagement, is reducing spam the most impactful?” This comparative approach requires us to explore a range of potential opportunities before settling on a target. By considering multiple opportunities, we can ensure we are focusing our efforts on solving the most important problems and achieving the most significant outcomes.

The Opportunity Solution Tree: Visualizing Compare and Contrast

To overcome these pitfalls and foster more effective product decision-making, we need tools and frameworks that encourage comparative thinking. This is where the Opportunity Solution Tree comes in. Inspired by the work of Anders Ericsson, author of Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, the Opportunity Solution Tree is a visual tool designed to externalize our mental representations and facilitate shared understanding within product teams.

Ericsson argues that experts differentiate themselves from novices by using more sophisticated mental representations – pre-existing patterns of information that enable them to process information, make decisions, and respond effectively in complex situations. For product teams, the challenge is to create a shared mental representation from the combined knowledge of the team, enabling faster and better decisions.

Diagram illustrating the structure of an Opportunity Solution Tree, starting with a desired outcome and branching out into opportunities, solutions, and experiments.

The Opportunity Solution Tree is my answer to the question: “How can we externalize our individual mental models and align our teams around a shared, visual representation of our product strategy?” It provides a framework for moving from a desired outcome to a set of prioritized opportunities, and then to a range of potential solutions, all while encouraging “compare and contrast” thinking at each stage.

Starting with a Clear Desired Outcome

The foundation of the Opportunity Solution Tree is a clearly defined desired outcome. What business or user outcome are we aiming to achieve? For my alumni community startup, the desired outcome was to “increase alumni engagement.” This provides a clear direction for all subsequent discovery and decision-making.

However, a desired outcome alone is insufficient. We need to explore how to achieve that outcome. This leads us to the next level of the tree: opportunities.

Opportunities Emerging from Research

Opportunities represent problems, needs, desires, or pain points that, if addressed, would contribute to achieving the desired outcome. These opportunities should not be based on assumptions or hunches, but rather emerge from generative user research, such as customer interviews and observations.

Image emphasizing the research-driven nature of opportunity identification in the Opportunity Solution Tree.

In our alumni community example, after conducting user interviews, we could have identified a range of opportunities expressed in the users’ own words:

- “I get too much email.”

- “I’m moving to a new city and want to know who lives there.”

- “I need help finding a job.”

- “I want to stay connected to my alma mater.”

- “I want to know what my college friends are up to.”

- “I’m looking for something interesting to read/learn.”

- “I want to keep up with my school’s sports.”

- “I want to hire a recent grad.”

- “I’m willing to donate but want to know the impact.”

- “I’d like to give back to the community.”

- “I’d enjoy mentoring a student or recent grad.”

This list, directly derived from user research, provides a rich set of potential areas to explore. However, prioritizing a long, unstructured list can be challenging.

Simplifying Prioritization Through Grouping

To make prioritization more manageable, the Opportunity Solution Tree encourages grouping similar opportunities together. This helps to simplify the “compare and contrast” process. Instead of comparing every item on a long list against each other, we can compare groups of related opportunities.

Diagram showing grouped opportunities, simplifying the prioritization process.

In our example, we can group the initial list into broader categories:

- “I need help”: (Includes “I need help finding a job,” “I’m moving to a new city and want to know who lives there.”)

- “I want to stay connected to my alma mater”: (Includes “I want to know what my college friends are up to,” “I want to keep up with my school’s sports,” “I’m looking for something interesting to read/learn.”)

- “I want to give back to the community”: (Includes “I’m willing to donate but want to know the impact,” “I’d like to give back to the community,” “I’d enjoy mentoring a student or recent grad,” “I want to hire a recent grad.”)

By grouping, we reduce the prioritization task to comparing these three higher-level opportunities. Our research indicated that “I need help” was a particularly prevalent theme. Interestingly, “I get too much email” (the spam problem) also falls under the broader umbrella of “I need help” – specifically, help filtering out irrelevant information.

Diagram highlighting the “I need help” opportunity as a primary focus area.

This revised structure starts to bridge the gap between my focus on spam reduction and Seth’s interest in connecting alumni geographically. Instead of arguing about specific solutions, we can now have a more productive conversation about which opportunity to prioritize within the “I need help” category.

Structuring Opportunities for Effective Comparison

The way we structure our opportunities within the tree is crucial for facilitating effective “compare and contrast” decisions. There isn’t one “right” way to structure it; the structure should reflect the user research findings and support meaningful prioritization.

Diagram emphasizing the iterative nature of opportunity structuring in the Opportunity Solution Tree.

For example, we could refine the structure to better reflect the interconnectedness of opportunities. Merging “I need help” and “I want to give back” into a broader opportunity like “I want to connect with other alumni” might be more insightful. Under this, we could have sub-opportunities:

- “I want to connect with alumni professionally.”

- “I want to connect with people near me.”

- “I don’t know who to connect with.”

This revised structure brings together both sides of the alumni network – those seeking help and those offering it – under a common umbrella. This makes it easier to compare different types of connections (professional, geographical, etc.) without implicitly favoring one group over another. It also helps bridge the gap between my and Seth’s perspectives, allowing us to focus on a shared opportunity area and then use data to decide which sub-opportunity to prioritize.

Focusing Ideation on a Target Opportunity

Once we’ve prioritized an opportunity (or a sub-opportunity), we move to the solution level of the tree. It’s tempting to brainstorm solutions across multiple opportunities, but this can lead to a shallow and unfocused product strategy. Instead, the Opportunity Solution Tree advocates for focused ideation: generating multiple solutions for a single target opportunity.

Diagram illustrating the pitfall of generating single solutions for multiple opportunities, leading to a lack of depth.

Generating numerous ideas for one specific opportunity pushes us beyond the obvious, first-level solutions and encourages more creative and innovative thinking. It sets the stage for a robust “compare and contrast” evaluation of different solution approaches to address the same problem.

For example, if we decide to focus on the opportunity “I get too much email” (within the broader “I need help” context), we would brainstorm multiple solutions specifically for reducing email overload. These might include:

- Implementing better email filtering and categorization.

- Introducing digest emails that summarize key community activity.

- Developing alternative communication channels besides email (e.g., in-app notifications).

- Providing more granular email subscription settings.

Comparing and Contrasting Solutions Through Dot Voting and Experimentation

After generating a range of solutions for a target opportunity, the next step is to evaluate and select the most promising ones. Again, we want to avoid “whether or not” decisions (“Is this solution good?”). Instead, we want to engage in “compare and contrast”: “Which of these solutions looks most promising compared to the others?”

Diagram illustrating dot voting as a method for narrowing down solution options.

The Opportunity Solution Tree recommends a two-stage approach to solution evaluation:

-

Dot Voting: Use dot voting to quickly narrow down a larger list of solutions to a smaller, more manageable set (3-5). Dot voting leverages the collective wisdom of the team to identify the most promising ideas for further consideration.

-

Experimentation: For the shortlisted solutions, design and run experiments to gather data and compare their effectiveness. Instead of experimenting to validate a single solution (“Does this work?”), we experiment to compare solutions (“Which of these works best?”).

For instance, if our shortlisted solutions for reducing email overload are better filtering, digest emails, and alternative channels, we could design experiments to test each of these. For better filtering, we might prototype a new filtering UI and test user adoption. For digest emails, we could A/B test engagement rates with and without digests. For alternative channels, we could pilot in-app notifications and measure their usage.

By comparing the results of these experiments, we can make data-informed decisions about which solutions to prioritize and invest in. This comparative experimentation approach is far more effective than trying to evaluate each solution in isolation.

Benefits of Embracing “Compare and Contrast” with the Opportunity Solution Tree

The Opportunity Solution Tree, with its emphasis on visualizing opportunities, solutions, and experiments, helps product teams embrace the power of “compare and contrast” in their decision-making process. This leads to several significant benefits:

Image summarizing the key benefits of using Opportunity Solution Trees for product teams.

-

Reduced Opinion Battles: By visualizing the decision-making process and focusing on comparative evaluation based on data, the Opportunity Solution Tree helps to move discussions away from subjective opinions and towards objective comparisons.

-

Improved Decision Framing: The tree framework encourages teams to frame decisions as “compare and contrast” choices rather than “whether or not” judgments. This leads to more nuanced and effective evaluations.

-

Enhanced Alignment: The visual nature of the tree facilitates shared understanding and alignment within the team, ensuring everyone is working towards the same desired outcome and considering opportunities and solutions within a common framework.

-

Strategic Roadmap: The Opportunity Solution Tree serves as a dynamic discovery roadmap, visually communicating the team’s strategy, priorities, and learning journey to stakeholders and leadership.

Getting Started with Your Own Opportunity Solution Tree

To begin leveraging the power of “compare and contrast” in your product development process, consider adopting the Opportunity Solution Tree. Here are key steps to get started:

-

Define a Clear Desired Outcome: Start with a specific, measurable outcome you want to achieve.

-

Conduct Generative Research: Engage in user interviews and observations to uncover a range of opportunities related to your desired outcome.

-

Structure Your Opportunities: Group and structure opportunities in a way that reflects your research findings and facilitates meaningful comparison.

-

Prioritize Opportunities Row by Row: Systematically prioritize opportunities at each level of the tree, using data and team discussion.

-

Focus Ideation on a Target Opportunity: Generate a diverse set of solutions specifically for your prioritized opportunity.

-

Compare Solutions Through Experimentation: Use dot voting and experimentation to compare and contrast your solutions and make data-driven decisions.

Invitation to share experiences with using Opportunity Solution Trees.

By embracing the principles of “compare and contrast” and utilizing tools like the Opportunity Solution Tree, product teams can move beyond subjective decision-making and build products that are truly impactful and user-centered. I encourage you to experiment with this approach and see how it can transform your product discovery process. If you build your own Opportunity Solution Tree, I’d love to hear about your experience!