India is on the verge of becoming the world’s most populous nation, overtaking China in 2023. This significant demographic shift prompts a crucial examination of India’s population dynamics, especially when juxtaposed with the United States, the third most populous country. Understanding the size of India compared to the US in terms of population, age distribution, fertility rates, and other demographic indicators is essential for grasping global population trends and their implications.

This analysis delves into key facts about India’s population and contrasts them with the demographic landscape of the United States. Drawing upon data from the United Nations and other reliable sources like Pew Research Center, we aim to provide a comprehensive comparison, highlighting the disparities and similarities between these two significant global players.

How We Analyzed the Data

The insights presented here are primarily derived from the United Nations’ World Population Prospects 2022 report. The UN’s estimates are meticulously compiled, considering “all available sources of data on population size and levels of fertility, mortality and international migration.” Historical population data for India is sourced from its decennial census, a comprehensive data collection effort since 1881. Fertility and related factors are analyzed using data from India’s National Family Health Survey (NFHS), a nationally representative household survey providing detailed information on childbearing. Migration data is mainly sourced from the United Nations Population Division.

The UN employs probabilistic methods to project future population trends, acknowledging the inherent uncertainties in fertility and mortality rates. The “medium scenario” projection, considered the central estimate, is derived from numerous simulations. “High” and “low” scenario projections factor in variations in fertility rates to provide a range of possible population futures. Additional sources are cited throughout this analysis to provide further context and depth.

India’s Massive Population Growth vs. the US: Since 1950, when the UN began compiling population data, India’s population has surged by over 1 billion people. While the exact current population is estimated to be over 1.4 billion due to the absence of a census since 2011, this figure surpasses the entire population of Europe or the Americas. Although both India and China have populations exceeding 1.4 billion, China’s population is now experiencing decline, whereas India’s continues to grow. This stark contrast highlights a key difference in the population size of India compared to the US, where the US population is considerably smaller.

Under the UN’s “medium variant” projection, India’s population is expected to exceed 1.5 billion before 2030 and peak at 1.7 billion in 2064. In a “high variant” scenario, India could reach 2 billion by 2068. Conversely, a “low variant” scenario projects a population decline starting in 2047, falling to 1 billion by 2100. These projections underscore the dynamic nature of India’s population growth trajectory compared to the more stable and slower growth rate of the US.

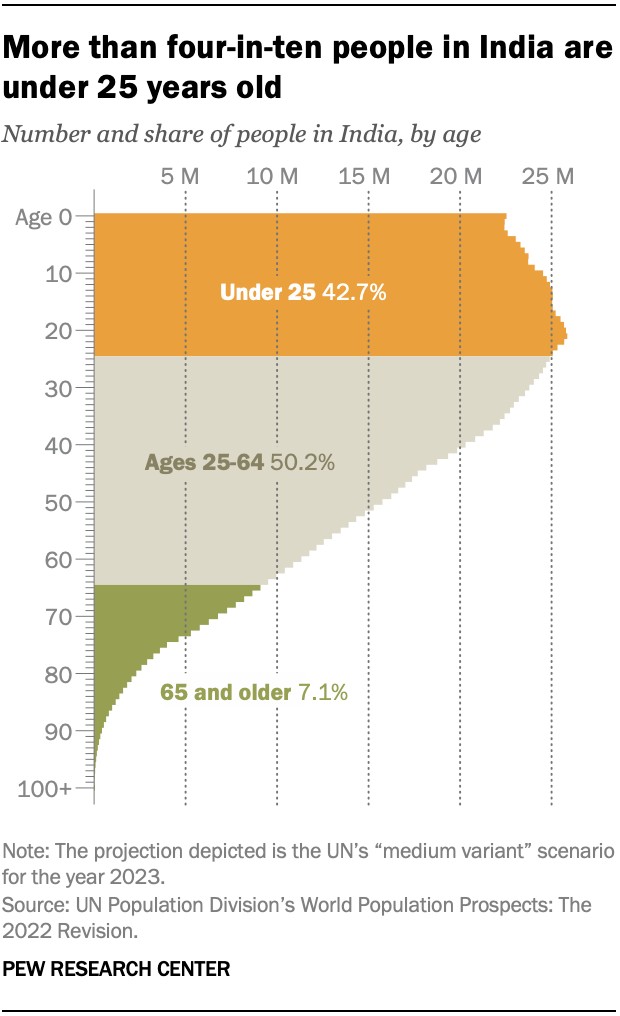

Youthful Demographics in India Contrasted with an Aging US Population: A striking demographic feature of India is its young population. Individuals under 25 years old constitute over 40% of India’s population. Remarkably, approximately one in five people globally under the age of 25 reside in India. The median age in India is 28, significantly younger than the median age of 38 in the United States. This youthful demographic structure sets India apart from the US, which, like many developed nations, faces an aging population.

In contrast to India, both China and the United States are experiencing rapid population aging. Adults aged 65 and older comprise only 7% of India’s population, compared to 18% in the US. Projections indicate that the proportion of older adults in India will remain below 20% until 2063 and will not approach 30% until 2100. This aging disparity is a critical aspect when comparing the size of India compared to the US in terms of demographic composition and future workforce potential.

Fertility Rates: India Still Higher, but Declining, Compared to the US: India’s fertility rate, while higher than both China and the US, has undergone a significant decline in recent decades. Currently, the average Indian woman is expected to have 2.0 children in her lifetime. This is higher than the US rate of 1.6, but considerably lower than India’s own rate of 5.9 in 1950 and 3.4 in 1992. This decline is observed across all religious groups in India, including Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains. For instance, the fertility rate among Indian Muslims has dropped from 4.4 children per woman in 1992 to 2.4 in 2019. While religious groups’ fertility rates are converging, India’s overall rate remains slightly above replacement level, contributing to its continued population growth, unlike the US where the rate is below replacement.

Fertility rates within India exhibit considerable variation based on community type and state. Rural women average 2.1 children, while urban women average 1.6, according to the 2019-21 NFHS. These figures were significantly higher 20 years prior, at 3.7 and 2.7 respectively. State-level fertility rates also vary widely, from highs of nearly 3 in Bihar and Meghalaya to lows around 1 in Sikkim and Goa. Similarly, population growth rates differ across states, reflecting disparities in economic opportunities and quality of life, factors less pronounced in the more uniformly developed United States.

Later Motherhood in Urban India Compared to Rural Areas: Indian women in urban areas tend to have their first child 1.5 years later than women in rural areas. The median age at first birth for urban women aged 25 to 49 is 22.3, compared to 20.8 for rural women in the same age group (2019 NFHS). Higher education and wealth are also correlated with delayed motherhood. Women with 12 or more years of schooling have a median age at first birth of 24.9, compared to 19.9 for women with no schooling. Similarly, women in the highest wealth quintile have their first child at a median age of 23.2, versus 20.3 for those in the lowest quintile. Among religious groups, Jains have the highest median age at first birth (24.9), and Muslims the lowest (20.8). While age at first birth is increasing in India, it generally remains lower than in the US, reflecting different societal norms and economic structures.

Improving Sex Ratio at Birth in India: India has historically faced a skewed sex ratio at birth, favoring boys, due to sex-selective abortions. However, this imbalance is narrowing. From approximately 111 boys per 100 girls in the 2011 census, the ratio has improved to about 108 boys per 100 girls in the 2019-21 NFHS. The estimated annual number of “missing” baby girls in India decreased from 480,000 in 2010 to 410,000 in 2019. While disparities across religious groups in sex ratios at birth are also diminishing, this remains a sensitive issue in India, unlike in the US where sex ratios are naturally balanced.

Infant Mortality: India Improving, but Still Higher than the US: Infant mortality in India has drastically decreased by 70% in the last three decades, falling from 89 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 27 in 2020. This represents significant progress. However, India’s infant mortality rate remains higher than its neighbors like Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, and substantially higher than developed nations like China and the United States (both at 6 and 5 deaths per 1,000 live births, respectively). This disparity in infant mortality is another critical point when considering the overall well-being and development indicators related to the size of India compared to the US in population and healthcare infrastructure.

Net Migration: India Experiences Out-migration, US Attracts Migrants: India typically experiences negative net migration, meaning more people emigrate from India annually than immigrate into it. In 2021, India’s net migration loss was around 300,000 people. UN projections suggest this trend will continue. In contrast, the United States is a major destination for international migrants and generally experiences positive net migration. This difference in migration patterns further shapes the demographic profiles of India and the US.

Historically, there have been periods of positive net migration in India, such as in 2016, likely due to refugee influxes. However, the overall trend indicates that emigration from India is more prevalent than immigration, contrasting sharply with the US, a nation built on immigration and continuing to attract global migrants.

Conclusion:

Comparing the size of India compared to the US reveals profound demographic differences. India’s population is not only significantly larger but also younger and still growing, albeit at a declining rate. In contrast, the US has a smaller, aging population with below-replacement fertility rates and positive net migration. While India has made remarkable progress in areas like infant mortality and sex ratio at birth, disparities within the country, particularly across states and between rural and urban areas, remain significant. Understanding these demographic contrasts is crucial for policymakers, researchers, and anyone interested in the evolving global landscape and the distinct challenges and opportunities faced by India and the United States in the 21st century.