Introduction

Effective communication between healthcare providers and patients is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of quality medical care, significantly shaping patient experiences and outcomes. The language used by medical practitioners, particularly when discussing potentially uncomfortable or painful procedures, can profoundly influence a patient’s perception of pain and anxiety. [1] For instance, using negatively charged phrases like “big bee sting” when describing an intravenous cannula insertion can heighten a patient’s anticipation of pain, whereas gentler phrasing such as “numbing the area” can improve pain perception and overall comfort. [2, 3] Neuroimaging studies have shed light on this phenomenon, demonstrating that negative suggestions can modulate pain processing within the anterior cingulate cortex, a brain region connecting the limbic system (emotions) and the sensory cortex (pain perception). [4, 5] The very word “pain” can act as a negative suggestion, triggering a subconscious shift in a patient’s mood, perception, and behavior. [6]

Postoperative pain management relies heavily on accurate pain assessment. Clinical practice commonly employs simple, validated scales such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the Verbal Numerical Rating Scale (VNRS). [7] Emerging research suggests that even the terminology used in these assessments—specifically, using “comfort” instead of “pain”—can significantly alter a patient’s recovery experience. [8, 9, 10] However, more research is needed to solidify these findings and explore their implications across diverse patient populations.

To address this gap, we conducted a single-blinded Randomized Comparative Experiment. This study aimed to compare standard pain scores with comfort scores in women recovering from cesarean sections. Our primary objective was to determine if the method of pain assessment, by framing questions around “pain” versus “comfort,” impacts patients’ perceptions and experiences in the postoperative period. This randomized comparative experiment provides valuable insights into the subtle yet powerful influence of language in healthcare.

Subjects and Methods

This meticulously designed randomized comparative experiment received approval from the local Institutional Ethics Committee and was prospectively registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (www.ctri.nic.in, registration number CTRI/2017/03/008248). We recruited 180 women who had undergone cesarean sections and, prior to their post-anesthesia review, randomized them into two groups, each comprising ninety participants, using a computer-generated randomization sequence.

Participants were selected based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible women were over 18 years of age and had undergone a cesarean section. Exclusion criteria included women under 18 years of age, those with hearing or speech impairments, patients with intellectual disabilities, and individuals with a history of chronic pain or opiate abuse. These criteria ensured the study focused on a homogenous group and minimized confounding factors.

Data collection involved structured interviews conducted by trained researchers between 10 and 30 hours post-cesarean section. To maintain blinding, participants were unaware of the study intervention. However, due to the nature of the intervention (question wording), the assessors were not blinded to group allocation. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants after the post-anesthesia interview to preserve participant blinding during the assessment.

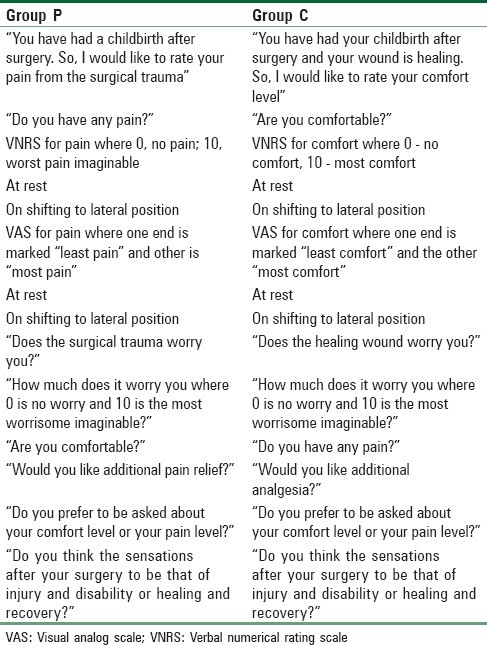

Group P (Pain group) participants were administered a structured questionnaire [Table 1] focused on pain assessment. They were asked, “You have had childbirth after surgery. I would like to assess your pain from the surgical trauma,” followed by “Do you have any pain?”. Subsequently, they quantified their postoperative pain levels at rest and during movement to a lateral position using a 0-10 point VNRS, where 0 represented “no pain” and 10 signified “the worst pain imaginable.” A VAS, marked “least pain” at one end and “most pain” at the other, with a 0-10 cm scale on the reverse side [Figure 1a], was also utilized. Additionally, they rated their worry related to the surgical trauma on a 0-10 point VNRS (0 = “no worry,” 10 = “most worry imaginable”), their comfort level, and their need for additional analgesia.

Group C (Comfort group) participants received a similar structured questionnaire [Table 1], but with a focus on comfort assessment. They were asked, “You have had your childbirth after surgery, and your wound is healing. I would like to assess your comfort level,” followed by “Are you comfortable?”. They then quantified their comfort level at rest and during movement to a lateral position using a 0-10 point VNRS, where 0 represented “no comfort” and 10 signified “most comfort.” A VAS for comfort, marked “most comfort” and “least comfort” at opposite ends, with a 0-10 cm scale [Figure 1b], was also employed. They also rated their worry related to healing (0-10 VNRS), their pain level, and need for additional analgesia. Both groups were asked about their perceptions of postoperative sensations (injury vs. healing) and their preference for comfort-focused or pain-focused questioning.

The primary outcome of this randomized comparative experiment was to compare the incidence of reported pain and pain severity, as measured by the VNRS for pain in Group P and the inverted VNRS for comfort in Group C. Secondary outcomes included comparing pain severity using VAS, assessing worry levels, evaluating the need for additional analgesia, determining patient preference for question type, and comparing perceptions of the surgical wound as either injury/disability or healing/recovery.

Table 1. Structured questionnaire for Group P and Group C

Figure 1. Visual analog scale for pain and for comfort.

Power of Study

Sample size calculation was based on previous research [10] indicating that 79% of women in a “pain” group reported comfort, compared to 94% in a “comfort” group. To achieve a power of 90% with an alpha of 0.05, beta of 0.20, and a 95% confidence interval, a sample size of ninety participants per group was determined to be necessary for this randomized comparative experiment.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous data are presented as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, depending on data distribution. Normality was assessed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Normally distributed data were analyzed using Student’s t-tests, while skewed or ordered categorical data were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-tests. Categorical data comparisons were performed using Pearson Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. All tests were two-sided, with a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

The participant flow throughout this randomized comparative experiment is detailed in the CONSORT diagram [Figure 2]. Initially, 183 women were screened for eligibility post-cesarean section. Three were excluded due to intellectual disability, leaving 180 women who were randomized, interviewed, and included in the final analysis. Baseline characteristics, anesthetic techniques, and postoperative analgesia were comparable between the two groups, as detailed in [Table 2], ensuring that observed differences were likely attributable to the intervention.

Figure 2. CONSORT diagram

Table 2. Baseline patient characteristic data in Groups P and C

Table 3 summarizes the key findings of this randomized comparative experiment, including the incidence of reported pain, VNRS and VAS scores at rest and during movement, patient perceptions of the postoperative wound, and worry scores for both groups.

Table 3. Women reporting pain, verbal numerical rating scale, and visual analog scale at rest and movement, patient perceptions of postoperative wound

In Group P, a significantly higher proportion of women (68.9%) reported pain when directly asked “Do you have any pain?” compared to Group C (54.4%) (P < 0.05). However, when asked about comfort (“Are you comfortable?”), there was no significant difference in the proportion of women reporting comfort between Group P (87.8%) and Group C (88.9%) (P = 0.81).

Notably, despite the difference in reported pain incidence, there were no statistically significant differences in VNRS scores at rest (Group P: 2 [0-3] vs. Group C: 1 [0-2], P = 0.188) or during movement (Group P: 5 [3-6] vs. Group C: 5 [3-5], P = 0.119). Similarly, VAS scores at rest (Group P: 10 [0-30] vs. Group C: 10 [0-22.5], P = 0.733) and during movement (Group P: 45 [30-50] vs. Group C: 50 [50-70], P = 0.828) showed no significant intergroup differences.

While worry levels were numerically higher in Group P (45%) compared to Group C (33.33%), this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.093), and worry scores were similar in both groups (2 [0-5]).

A striking finding of this randomized comparative experiment was the significant difference in patient perceptions of their postoperative wound. In Group P, 33.33% of women perceived their sensations as injury and disability, whereas in Group C, only 12.22% held this perception (P < 0.001). Conversely, a larger proportion of women in Group C (86.66%) viewed their postoperative sensations as healing and recovery compared to Group P (65.55%).

Patient preference for question type also revealed interesting insights. A majority of women in both groups preferred being asked about their comfort level over their pain level (Group P: 67.77%, Group C: 74.44%). Only 16 out of 180 women expressed no preference.

Discussion

This single-blinded randomized comparative experiment provides compelling evidence regarding the impact of language in pain assessment, specifically comparing the use of “comfort” versus “pain” in postoperative questionnaires. Our findings corroborate previous studies [8, 9] demonstrating that women are significantly more likely to report pain when directly asked “Do you have any pain?” compared to when asked about their comfort level. This may be attributed to the negative suggestion inherent in the word “pain,” potentially eliciting a pain response that might not otherwise be consciously experienced.

Despite the reduced incidence of reported pain in the comfort-focused group, our study found no significant differences in pain severity scores (VNRS and VAS) between the groups. This suggests that while framing questions around comfort can decrease the reporting of pain, it does not mask or alter the underlying pain experience itself when measured directly. The similar severity scores align with findings from a 2011 study by Chooi et al., which also found no difference in pain scores or analgesia requirements between pain and comfort assessment groups.

A key contribution of this randomized comparative experiment is the demonstration that comfort-focused language positively influences patients’ perceptions of their postoperative recovery. Significantly fewer women in the comfort group perceived their postoperative sensations as injury and disability, instead viewing them as part of the healing and recovery process. This aligns with the 2013 findings of Chooi et al., highlighting the potential of positive language to shape patient perceptions of their surgical experience.

The observed patient preference for comfort-focused questioning further underscores the importance of language in healthcare communication. Patients reported that the word “pain” evoked negative feelings and reminded them of suffering, while “comfort” provided a more positive and reassuring connotation.

This study acknowledges certain limitations. The lack of a perfect antonym for “pain” raises questions about the direct comparability of pain and comfort assessments. Inverting comfort scores for statistical comparison, while a common practice, may not perfectly capture the subjective equivalence between a specific pain level and a corresponding comfort level. Furthermore, assessments were conducted at a separate time from routine ward rounds, and the study did not account for pain-related questioning by other healthcare staff prior to our assessment. Finally, due to resource constraints, patients were assessed only once, and the study did not track the long-term need for additional analgesics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this randomized comparative experiment demonstrates that employing comfort-focused language in postoperative pain assessment can effectively reduce the reported incidence of pain without diminishing its measured severity. Moreover, using positive words like “comfort” significantly improves patients’ perceptions and experiences following surgery, fostering a more positive outlook on their recovery. These findings strongly advocate for the mindful use of language in healthcare settings, particularly in postoperative care, to enhance patient comfort and promote a more positive healing journey.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Ms. Kusum Chopra for analyzing data of the study.

References

[1] Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000 Mar;85(3):317-32.

[2] Christenfeld N, Leckridge BJ, Mayer ML. Does the language of pain influence pain reports? Pain. 1999 Oct;83(1):147-51.

[3] Lander J,ীনরণ, Hodson K, Nazarali R, McTaggart R. Verbal suggestion and post-operative pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Pain. 1996 Feb;64(2):325-32.

[4] Lorenz J, Minoshima S, Casey KL. Cortical systems for pain processing in chronic pain. Arch Neurol. 2003 Dec;60(12):1727-35.

[5] Peyron R, Laurent B, García-Larrea L. Functional imaging of brain responses to noxious stimuli. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000 Feb;111(2):183-204.

[6] Benedetti F, Amanzio M. The neurobiology of placebo analgesia. Dis Mon. 2007 Nov;53(11):670-92.

[7] Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978 Nov;37(6):378-81.

[8] Chooi C, Kurz A, Chan MT, Gillam L, faced A. Comfort score vs pain score in assessing pain after cesarean delivery. J Pain. 2013 Jul;14(7):707-12.

[9] Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, White W, Apfelbaum JL, Chung F, et al. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2007 Dec;105(6):1615-28.

[10] Chooi C, Cox M, Smith I, Pandit R, Calverley R, MacLeod A, et al. A comparison of pain scores and comfort scores after day-case surgery. Anaesthesia. 2011 Nov;66(11):959-64.