In the realm of physics, sound manifests as a pressure wave, originating from the vibrations of an object and propagating through a medium. This propagation occurs as a chain reaction: when an object vibrates, it disturbs adjacent air molecules, causing them to vibrate and subsequently transmit this vibrational energy throughout the medium. While physiology considers sound in terms of its reception by the human ear, physics recognizes sound’s independent existence as a physical phenomenon. This perspective, rooted in physics, emphasizes the nature of sound waves, which we will explore in greater detail.

Exploring the Spectrum of Sound: Types and Frequencies

Sound exists in a diverse range of forms, categorized by their audibility, pleasantness, and loudness, among other qualities. We perceive music as organized and often pleasant sound, while noise is typically characterized as disorganized and undesirable. Importantly, the human ear is limited in its perception, capable of hearing frequencies between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz. Sounds outside this range are classified as either infrasonic or ultrasonic. Infrasonic waves, below 20 Hz, and ultrasonic waves, above 20,000 Hz, are inaudible to humans but play significant roles in various natural and technological applications.

Infrasonic Waves: Below the Threshold of Hearing

Infrasonic waves, characterized by frequencies below 20 Hz, are beyond the range of human hearing. Despite our inability to perceive them directly, infrasound waves are invaluable in scientific and natural contexts. Scientists utilize infrasound for monitoring seismic activity, such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, and for subsurface geological mapping in the search for minerals and petroleum. Interestingly, many animal species employ infrasound for long-distance communication. Whales, elephants, and other large animals communicate across vast distances using these low-frequency waves, leveraging their ability to travel great distances with minimal attenuation.

Ultrasonic Waves: Beyond Human Perception

Ultrasonic waves operate at frequencies exceeding 20,000 Hz, placing them above the human auditory limit. While inaudible to us, ultrasound has become a cornerstone of medical diagnostics, most notably in sonography, which allows visualization of internal organs. Beyond medicine, ultrasound technology is applied in navigation systems, industrial imaging, material testing, and even in certain forms of communication. In the natural world, bats are a prime example of creatures using ultrasound for echolocation, emitting these high-frequency sounds to navigate and hunt in their environment.

The Genesis of Sound: Vibrations and Molecular Motion

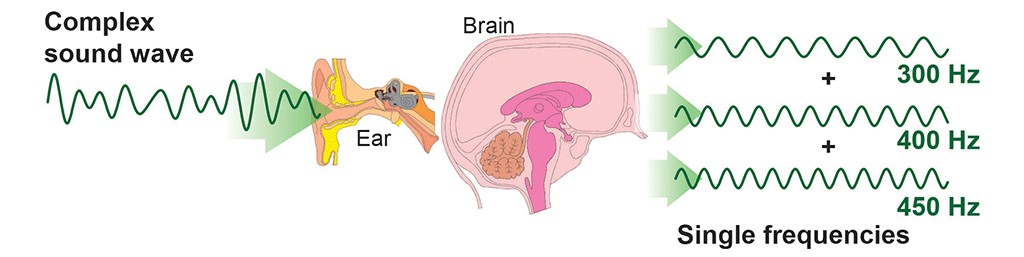

Sound production is fundamentally linked to vibration. When an object vibrates, it imparts kinetic energy to the surrounding medium, initiating a pressure wave. This wave is not a movement of the medium itself, but rather a propagation of energy through it. Consider air, water, or solids as mediums; in each, vibrating objects cause the medium’s particles (molecules) to oscillate. This oscillation is passed from one molecule to the next, creating a chain reaction that transmits the sound energy. Our ears detect these sound waves when the vibrating air particles cause parts within our ear to vibrate, translating mechanical wave energy into auditory signals.

Sound waves share similarities with light waves in that both originate from a source and can be manipulated. However, a key difference lies in their propagation: sound waves are mechanical waves, requiring a medium to travel, unlike light waves which can travel through a vacuum. This medium dependency explains why sound cannot travel in the vacuum of space.

Sound Propagation: How Mechanical Waves Travel Through Media

The Role of the Medium in Sound Transmission

The medium through which sound travels significantly affects its speed and propagation. Sound waves are mechanical waves, meaning their energy transfer is dependent on the properties of the medium. Sound travels most efficiently through solids, followed by liquids, and then gases. This is because the density of molecules is highest in solids, allowing for more rapid transfer of vibrational energy between molecules. In liquids, molecules are less densely packed but still permit efficient sound transmission, with sound traveling much faster in water than in air. Air, being the least dense, results in the slowest sound propagation among these states of matter. Factors like wind speed in air can further impede sound wave propagation by dissipating wave energy.

Medium Density and the Speed of Sound

The speed of sound is intrinsically linked to the medium’s properties, particularly its density and temperature. In dry air at 20°C, sound travels at approximately 343 meters per second. In contrast, through room temperature seawater, sound accelerates to about 1531 meters per second. This difference underscores the medium’s influence. Phenomena like shockwaves occur when a disturbance exceeds the local speed of sound, as observed with supersonic aircraft. Temperature also plays a role; generally, warmer media facilitate faster sound travel. This is a relevant consideration in the context of global warming and its potential impact on oceanic sound propagation speeds.

Molecular Dynamics in Wave Propagation

Sound wave propagation is a process of energy transfer through molecular interactions. When an object vibrates, it initiates kinetic energy. This energy is then transmitted through the medium as vibrating sound waves interact with the medium’s molecules. As a wave encounters air particles, it transfers its kinetic energy, causing these molecules to move. These energized molecules, in turn, collide with and energize neighboring molecules, continuing the process of energy transmission. This can be visualized with a slinky: a push on one end creates a compression wave that travels down its length. Similarly, sound waves propagate through compressions and rarefactions, analogous to the slinky’s coils compressing and expanding.

Compressions and Rarefactions: The Wave Pattern

Sound waves are characterized by alternating regions of compression and rarefaction. Compression occurs where molecules are forced closer together, increasing density and pressure. Rarefaction, conversely, is where molecules are spread apart, resulting in decreased density and pressure. As a sound wave travels, it creates this pattern of compressions and rarefactions. It’s crucial to understand that individual molecules in the medium do not travel with the sound wave itself. Instead, they oscillate around their equilibrium positions, transferring energy to adjacent molecules. This transfer of energy is what manifests as the wave, creating the dynamic pattern of compression and rarefaction. The distance comprising one compression and one rarefaction defines the wavelength of a sound wave. Sound energy diminishes as it propagates, explaining why distant sounds are fainter. Reflection of sound waves by surfaces leads to echoes, a phenomenon particularly noticeable in enclosed or expansive spaces like caves or canyons.

Categorizing Sound Waves: Longitudinal, Mechanical, and Pressure Waves

Sound waves are classified into three main types, reflecting their fundamental nature: longitudinal waves, mechanical waves, and pressure waves. These classifications help to understand the underlying physics of sound propagation and behavior.

Longitudinal Sound Waves: Parallel Molecular Motion

Longitudinal waves are defined by the motion of the medium’s particles being parallel to the direction of energy transport. Sound waves in air and fluids are prime examples of longitudinal waves. When a sound wave travels, the molecules in the medium vibrate back and forth in the same direction as the wave’s propagation. Imagine pushing a slinky back and forth along its length; the coils move parallel to the direction of the push. Similarly, when a tuning fork vibrates, the air particles oscillate parallel to the direction the sound wave travels outward. This parallel motion is the defining characteristic of longitudinal sound waves.

Mechanical Sound Waves: Energy Transfer Through a Medium

A mechanical wave is characterized by its dependence on the oscillation of matter for energy transfer. These waves require a medium to propagate, as they involve the mechanical displacement of particles within that medium. Sound waves are inherently mechanical waves. The initial energy input, such as a vibrating object, is transmitted through the medium as particles interact and transfer energy. Other examples of mechanical waves include water waves, seismic waves, and internal water waves within oceans. Mechanical waves can be further categorized into transverse, longitudinal, and surface waves.

Sound is a mechanical wave because its propagation through air involves a chain reaction of air particles displacing each other. As one particle is disturbed, it interacts with and displaces its neighbors, transmitting the disturbance and thus the sound energy through the medium. This particle-to-particle interaction, driven by mechanical vibrations, is why sound is classified as a mechanical wave. Sound energy, originating from a vibrating source, necessitates a medium for transmission, reinforcing its mechanical nature.

Teaching Tools for Sound Wave Exploration

Wireless Sound Sensor

The Wireless Sound Sensor is an invaluable tool for educational explorations of sound. It integrates both a sound wave sensor, for measuring relative changes in sound pressure, and a sound level sensor with dBA- and dBC-weighted scales. With real-time data reporting and versatile display options, including FFT and oscilloscope views, it’s adaptable for introductory sound experiments as well as advanced scientific investigations. Its portability and robust software enhance its utility in studying sound phenomena.

Wireless Sound Sensor: A versatile tool for measuring sound pressure and sound levels, facilitating hands-on investigations into sound wave properties and behavior in educational settings.

Pressure Sound Waves: Fluctuations in Medium Pressure

Pressure waves, also known as compression waves, are characterized by regular patterns of high and low-pressure regions. Sound waves inherently exhibit these pressure variations, consisting of compressions (high-pressure regions) and rarefactions (low-pressure regions). This fluctuation in pressure is a fundamental aspect of sound wave propagation. As sound waves reach the human ear, they are detected as these alternating pressure variations, with compressions perceived as high pressure and rarefactions as low pressure. This pressure variation is the basis for how sound is sensed and interpreted.

Transverse Waves: Perpendicular Oscillations

Transverse waves, in contrast to longitudinal waves, exhibit oscillations perpendicular to the direction of wave travel. Sound waves in their typical form are not transverse waves, as their oscillations are parallel to the direction of energy transport. However, under specific conditions, sound waves can exhibit transverse characteristics, particularly in solids. Transverse sound waves, also known as shear waves, propagate slower than longitudinal waves and are primarily observed in solid media. Ocean waves are a common example of transverse waves in nature. A simple demonstration involves shaking a string up and down, creating a wave that moves perpendicularly to the direction of the shake.

Visual comparison of longitudinal and transverse waves.

Creating Standing Waves: Wave Interference and Resonance

Standing waves, patterns of constructive and destructive interference, can be created using tools like PASCO’s String Vibrator, Sine Wave Generator, and Strobe System. The Sine Wave Generator and String Vibrator work together to generate and propagate waves through a string or rope. The Strobe System can then be used to visually “freeze” the wave pattern, allowing for detailed observation of nodes and antinodes. This setup enables students to investigate wave phenomena in real-time, exploring the quantum nature of waves and observing wave properties directly.

Four Fundamental Properties of Sound

The distinction between music and noise, or the unique character of different sounds, arises from four key properties of sound: pitch, dynamics (loudness), timbre (tone color), and duration. These properties are fundamental to our perception and interpretation of sound.

Frequency (Pitch): High and Low Tones

Pitch is the perceptual quality that allows us to classify sounds as “high” or “low,” essentially organizing sounds along a frequency scale. Pitch is often considered the musical equivalent of frequency, though it is a subjective interpretation. A high-pitched sound corresponds to rapid molecular oscillations, while a low-pitched sound is associated with slower oscillations. Pitch perception requires a sound to have a clear and consistent frequency, distinguishing it from random noise. As pitch is primarily a listener’s subjective experience, it is not a purely objective physical property of sound.

Amplitude (Dynamics): Loudness and Softness

Amplitude determines the perceived loudness of a sound wave. In musical terms, loudness is referred to as dynamics. In physics, sound wave amplitude is measured in decibels (dB), though decibel scales do not directly correlate with musical dynamic levels. Higher amplitudes correspond to louder sounds, and lower amplitudes to softer sounds. However, human hearing sensitivity varies with frequency; sounds at very low and very high frequencies are often perceived as softer than mid-range frequencies, even at the same amplitude.

Timbre (Tone Color): The Unique Sound Signature

Timbre, or tone color, is the quality that gives each sound its unique “feel.” Different instruments or sound sources produce sounds with varying timbres, resulting from complex wave shapes. Timbre is what allows us to distinguish between a piano and a guitar playing the same note, or to recognize a friend’s voice. In physics, timbre is understood as the characteristic sound quality that enables sound identification.

Duration (Tempo/Rhythm): Time and Sound Length

Duration, in music, is the length of time a pitch or tone lasts. It can be described as long, short, or measured in specific time units. Duration influences both the rhythm and timbre of a sound. Classical music often features notes with longer durations compared to the shorter, quicker notes in pop music. In physics, sound duration is defined from the moment the sound is registered to the point it becomes undetectable.

Music Creation Through Sound Properties

Musicians manipulate these four properties of sound to create structured and patterned sequences that form music. Duration defines the length of musical sounds. Pitch, determined by the frequency of sound vibrations, dictates the perceived highness or lowness of a tone. Amplitude governs dynamics, or loudness, and timbre provides the unique tone color of different instruments. By varying these properties, musicians craft melodies, harmonies, and rhythms that evoke different emotions and experiences.

Music vs. Noise: Order and Randomness in Sound

Acousticians, the scientists studying sound acoustics, differentiate between noise and music based on their structure and human perception. Noise is often characterized as randomized and unpleasant sound waves, while music is defined by constructed, patterned sound waves. Studies indicate that the human body responds differently to noise and music, potentially explaining why structured music is generally more pleasing than random noise.

Acoustics: The Science of Sound

Acoustics is an interdisciplinary science encompassing the study of mechanical waves, including vibration, sound, infrasound, and ultrasound, across various media like solids, liquids, and gases. Professionals in acoustics include acoustical engineers, who innovate sound-based technologies; audio engineers, specializing in sound recording and manipulation; and acousticians, who focus on the fundamental science of sound itself.

Teaching Tools for Exploring Sound Phenomena

Resonance Air Column Apparatus: A tool designed for demonstrating and investigating sound resonance and harmonics, useful in physics education to visualize wave properties.

Resonance Air Column: Demonstrating Wave Resonance

The Resonance Air Column is an effective tool for demonstrating wave phenomena, particularly resonance and harmonics. This apparatus consists of a hollow tube with a movable piston. As the piston is adjusted, distinct tones are produced at resonant points, corresponding to nodes within the air column. Students can use metersticks and rings to identify and measure the positions of nodes and antinodes, and Capstone software can provide real-time FFT displays for data analysis. This setup allows for experimental measurement and comparison with theoretical calculations of resonant frequencies and wave characteristics.

Key Characteristics of Sound Waves

Five primary characteristics define sound waves: wavelength, amplitude, frequency, time period, and velocity. Wavelength is the spatial period of the wave, the distance over which the wave pattern repeats. Amplitude relates to the intensity or loudness of the sound. Frequency is the number of wave cycles per second, determining pitch. The time period is the duration of one complete wave cycle. Velocity is the speed at which the wave propagates through the medium.

Sound wave diagram. A wave cycle occurs between two troughs.

Units of Sound Measurement

Sound is quantified using several units, each measuring different aspects of sound. The decibel (dB) is a logarithmic unit expressing the ratio of sound pressure to a reference pressure. Hertz (Hz) measures sound frequency, representing cycles per second. Phon and sone are also used in acoustics; a sone is a unit of perceived loudness, while a phon measures loudness level for pure tones, particularly reflecting subjective human perception of loudness.

Interpreting Sound Wave Graphs

Sound waves can be represented graphically in terms of displacement or density. Displacement-time graphs show the displacement of particles from their equilibrium positions over time, indicating the direction of movement. In such graphs, particles on the zero line are those experiencing maximum compression and rarefaction but minimal net displacement. Density-time or pressure-time graphs depict the regions of compression and rarefaction. In these graphs, particles on the zero line represent those that experience the least compression and rarefaction but undergo the largest back-and-forth motion.

Sound Pressure: Local Pressure Deviations

Sound pressure refers to the local deviation in pressure from the ambient atmospheric pressure caused by a sound wave. It’s distinct from static air pressure. As sound waves propagate, they induce fluctuations in pressure around the equilibrium atmospheric pressure. The speed of sound is generally not affected by air pressure itself, but sound pressure is the dynamic variation caused by the wave.

Sound Level: Relative Sound Pressure Measurement

Sound level is a measure of sound pressure relative to a reference level, expressed in decibels. Higher decibel values indicate higher sound levels. Instruments may measure sound level in dBc, which is the power ratio relative to a carrier signal, or in dBa, which are A-weighted decibels that adjust for human hearing sensitivity, reducing the weight of low-frequency sounds to better reflect perceived loudness.

Sound Level is a comparison of the sound wave’s pressure relative to the reference point. A dBc meter measures high and low frequencies, while a dBa meter measures mid-level frequencies.

Sound Intensity: Power per Unit Area

Sound intensity is defined as the power carried by a sound wave per unit area. It is a measure of the energy flux of the wave. Higher sound intensity correlates with larger amplitude oscillations and increased pressure exerted by the sound waves on objects in the medium. Decibels are also used to express sound intensity levels, typically referenced to the threshold of human hearing at 1000 Hz.

Sound Intensity is the power per unit area carried by a sound wave. The more intense the sound is, the larger the amplitude oscillations will be. As sound intensity increases, the pressure exerted by the sound waves on nearby objects also increases.

Sound Intensity in an Air Column: Resonance and Measurement

An air column, a tube open at one end and closed at the other, provides a controlled environment for studying sound characteristics, particularly intensity and resonance. Air columns facilitate investigations into nodes, antinodes, and resonance phenomena. They are valuable tools for demonstrating and measuring sound intensity variations under resonant conditions.

In conclusion, understanding sound waves requires grasping the interplay between molecular motion and mechanical wave energy transfer. Sound, as a mechanical wave, propagates through media via the vibration of molecules, creating patterns of compression and rarefaction that carry energy. From infrasound to ultrasound, and through properties like pitch, amplitude, timbre, and duration, sound presents a rich field of study within physics and acoustics. The tools and principles discussed provide a foundation for further exploration into the fascinating world of sound.