Planetary orbits around the sun, illustrating the gravitational dance between celestial bodies, relevant to understanding Mars gravitational pull compared to Earth's climate cycles

Planetary orbits around the sun, illustrating the gravitational dance between celestial bodies, relevant to understanding Mars gravitational pull compared to Earth's climate cycles

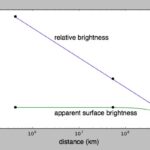

The intricate gravitational dance of planets within our solar system may hold more sway over Earth’s long-term climate than previously understood. New research suggests that the subtle gravitational pull of Mars could be a significant factor in stirring Earth’s oceans, influencing sediment shifts and contributing to a 2.4-million-year climate cycle. This “Grand Cycle,” as researchers are calling it, adds a new dimension to our understanding of the forces shaping Earth’s environment over vast stretches of time.

Scientists have long recognized the impact of Earth’s orbital wobbles around the sun, known as Milankovitch cycles, on our planet’s climate patterns over thousands of years. However, a team led by Adriana Dutkiewicz at the University of Sydney has now presented compelling evidence for a much longer cycle, operating over millions of years. This “Grand Cycle,” they propose, is linked to the gravitational influence of Mars and has demonstrably affected ocean currents for at least the past 40 million years.

The foundation for this discovery lies in the analysis of nearly 300 deep-sea drill cores. These cores, essentially geological time capsules, reveal unexpected variations in ocean sediment deposition. In periods characterized by stable ocean currents, sediment typically settles in consistent, even layers. However, the drill core data reveals inconsistencies and gaps in this sedimentary record, suggesting periods of turbulent ocean activity.

According to the research team, these disruptions in sediment deposition coincide with times when Mars’s gravitational force on Earth is at its peak. While seemingly minuscule, this gravitational tug subtly impacts Earth’s orbital dynamics. These orbital shifts, in turn, influence the amount of solar radiation reaching our planet, leading to climate variations that manifest as intensified ocean currents and eddies. The team posits that these stronger currents are responsible for the observed irregularities in the deep-sea sediment record.

Dietmar Müller, a member of the research team also from the University of Sydney, acknowledges the counterintuitive nature of Mars, a distant planet, exerting such influence. “The distance between Earth and Mars is immense, making it hard to imagine a significant gravitational force,” he states. “However, Earth’s climate system is incredibly complex, with numerous feedback mechanisms that can amplify even the most subtle external influences. In this context, Mars’s impact on Earth’s climate can be likened to a butterfly effect – a small initial change leading to significant downstream consequences.”

Benjamin Mills, a professor at the University of Leeds, UK, who was not directly involved in the study, supports the findings. He notes that the deep-sea drill core data provides further evidence for the existence of “megacycles” in Earth’s environmental history. “Many researchers have observed these multi-million-year cycles across various geological, geochemical, and biological records, including events like the Cambrian explosion of animal life,” Mills explains. “This study reinforces the importance of these long-term cycles as fundamental aspects of environmental change.”

However, Matthew England, a climate scientist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, expresses skepticism about the direct link to Mars. “While this research contributes to our understanding of long-term climate cycles, I remain unconvinced about Mars being the primary driver,” England states. “The gravitational pull of Mars on Earth is exceedingly weak – approximately one-millionth of the sun’s gravitational force. Even Jupiter exerts a stronger gravitational influence on Earth.” England emphasizes the need to consider other potential factors and scales of influence.

Despite the ongoing debate regarding the precise mechanisms and the extent of Mars’ influence, this research underscores the interconnectedness of our solar system and the multitude of factors that shape Earth’s long-term climate evolution. It’s crucial to remember, as England points out, that while these grand cycles operate over millions of years, the current climate crisis is overwhelmingly driven by human-induced greenhouse gas emissions. The impact of human activity is far more immediate and forceful than any subtle gravitational nudges from Mars, demanding urgent attention and action to mitigate its effects.

Journal Reference: Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-46171-5