Dog lovers have long proclaimed their furry companions’ brilliance, and now, science is increasingly backing up these claims. For over a decade, the study of canine behavior and intelligence has flourished, revealing that dogs possess a remarkable capacity for social intelligence and emotional depth. Psychologist and canine researcher Stanley Coren estimates that the average dog’s intellect is akin to that of a 2.5-year-old human child. But how does this truly stack up against human intelligence? Are dogs just mimicking behaviors, or is there genuine cognitive ability at play?

Research indicates that dogs are adept at interpreting human cues, forging deep emotional bonds with their owners, and even displaying complex emotions like jealousy. Some exceptionally bright dogs can learn hundreds of words, showcasing impressive memory and comprehension. These abilities are likely honed through evolution, as humans have selectively bred dogs for millennia, favoring those most attuned to coexisting with us.

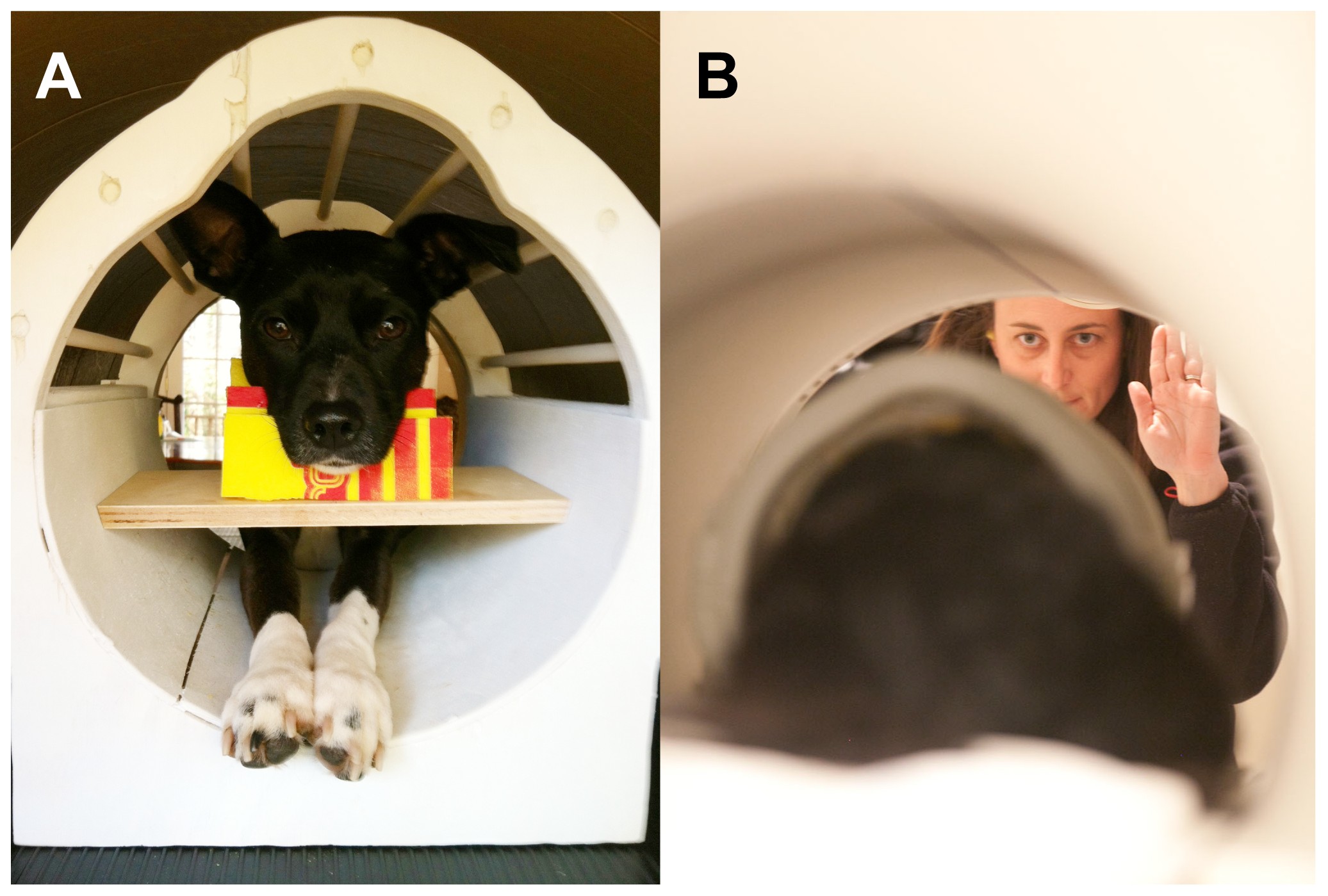

While the field of canine cognition is still evolving, the insights gained are profound. Gregory Berns, a neuroscientist at Emory University utilizing MRI technology to study dog brains, emphasizes dogs’ unique value in understanding social behaviors. “Dogs are unique animals, and I think in many ways they’re one of the best animals for understanding social behaviors,” Berns states, highlighting the growing recognition of dogs as crucial subjects in cognitive research. Employing advanced technologies and meticulously designed behavioral experiments, researchers worldwide are delving into the canine mind, uncovering a level of intelligence that often surpasses initial assumptions.

1) Exceptional Human Reading Skills: Dogs Outperform Chimps in Social Cues

It might be surprising, but in certain social intelligence tests, dogs outperform even chimpanzees, our closest primate relatives. A classic test of communication involves placing treats under one of two overturned cups. Humans point to the cup concealing the treat, a seemingly straightforward cue. However, chimpanzees and human infants younger than one year often fail to grasp this, choosing the correct cup only by chance.

Dogs, in contrast, excel at this task. Brian Hare, a researcher at Duke University, demonstrated through a series of experiments that dogs readily interpret human pointing, consistently selecting the baited cup at rates significantly above chance. This holds true even when both cups are scented with the treat. Dogs demonstrate a keen ability to understand human gestures like pointing, staring, and nodding as communicative signals.

Further experiments highlight this social intelligence. Dogs trained to resist taking food are significantly more likely to disobey when a human observer leaves the room, closes their eyes, or turns away. Understanding the significance of gaze direction in this context is a cognitive skill that appears to elude chimpanzees. Studies also reveal that dogs can discern our emotional reactions to objects and adjust their behavior accordingly. In one experiment, dogs observed their owners reacting positively to one box and negatively to another, without seeing the contents. Remarkably, the dogs overwhelmingly favored the box associated with positive human cues 81 percent of the time, mirroring the results observed in similar experiments with 18-month-old human infants. This emphasizes the sophisticated ability of dogs to interpret and respond to human emotional signals.

2) Vocabulary Mastery: Some Dogs Learn Hundreds of Words

While individual variation exists, much like in human populations, certain dogs exhibit remarkable memory capabilities, learning and retaining vocabularies exceeding 1,000 words. The most celebrated example is Chaser, a Border Collie trained by retired psychology professor John Pilley. Documented in a 2011 study in Behavioral Processes, Chaser learned the names of an astonishing 1,022 distinct toys. When instructed to retrieve a specific toy by name, she successfully fetched the correct one approximately 95 percent of the time. Expanding on this, Pilley further trained Chaser to comprehend verbs, enabling her to differentiate between actions like picking up, pawing, and nosing objects.

Chaser’s linguistic prowess, while exceptional, is not entirely unique. Rico, another Border Collie, has demonstrated recognition of over 200 different words and exhibits “fast-mapping,” a cognitive process where a new word is associated with a novel object, distinguishing it from known items. These cases underscore the potential for advanced language comprehension in dogs, exceeding initial expectations and blurring the lines in the human-animal communication spectrum.

3) Processing Words, Not Just Tone: Dogs Understand Speech Semantics

Contrary to popular belief that dogs primarily respond to the emotional tone of our voice, research suggests they process the semantic content of our speech as well. Victoria Ratcliffe, a psychology researcher at the University of Sussex, conducted experiments indicating that dog brains actively process the words we speak.

In humans, language processing is largely localized in the left brain hemisphere, while emotional tone is processed predominantly in the right hemisphere. Auditory information from the right ear is primarily directed to the left hemisphere, and vice versa. This results in a bias where language is often interpreted more strongly through right-ear input, and tone through left-ear input.

Ratcliffe’s research revealed a similar hemispheric bias in dogs. Using speakers positioned on either side of dogs, familiar commands and control sounds were played simultaneously. When familiar commands were uttered, dogs predominantly turned their heads to the right, indicating left hemisphere processing associated with language. Conversely, distorted speech or unfamiliar language commands elicited more leftward head turns, suggesting right hemisphere processing focused on tone and non-semantic auditory cues.

“This told us that they’re paying attention to different calls, and processing words they already know in a different way than others,” Ratcliffe explains. Her ongoing research delves into the specific information dogs associate with learned words, further illuminating the complexities of canine language comprehension. fMRI studies corroborate these findings. Research at Hungary’s Eötvös Loránd University demonstrates increased brain activity in specific “voice areas” of dogs when exposed to human speech compared to non-verbal sounds. Attila Andics, lead author of this fMRI research, noted the striking similarity in the location of these “voice areas” in both human and dog brains, highlighting a potential evolutionary convergence in vocal communication processing.

4) Deep Emotional Connections: Dogs Bond with Owners on a Neurological Level

Pioneering MRI research by Gregory Berns’ lab at Emory University has provided compelling evidence of the profound emotional bond between dogs and their owners. In a groundbreaking experiment, dogs were exposed to scent samples, including their owner’s scent. fMRI scans revealed a significant surge in activity within the caudate nucleus, a brain region associated with reward and emotional attachment, specifically when dogs inhaled their owner’s scent. This neural response was absent when exposed to stranger’s scents. Furthermore, the same caudate nucleus activation occurred when the owner entered the room, but not upon the arrival of strangers.

Subsequent experiments by Berns explored the caudate response in relation to treat signals given by different individuals. Dogs exhibiting lower scores on aggression tests showed a caudate response primarily attuned to their owners. More aggressive dogs, however, displayed similar reward system activation regardless of whether their owner or a stranger provided the treat signal. Berns’ lab is currently investigating the potential of these fMRI tests to identify dogs best suited for service roles, based on their neural responses to human interaction and bonding cues.

5) Experiencing Jealousy: Dogs Exhibit Complex Social Emotions

Traditionally, jealousy was considered a uniquely primate emotion. However, recent studies challenge this notion, providing evidence that dogs also experience jealousy. Researchers at the University of Vienna conducted an experiment where dogs were trained to offer their paw (“shake hands”) in exchange for a treat. In a subsequent experiment involving pairs of dogs, only one dog was rewarded for performing the paw-shake, while the other received no reward. Remarkably, the unrewarded dog soon ceased participating. This wasn’t mere frustration at lack of reward, as the same dogs persisted much longer when performing the task alone without witnessing another dog being rewarded.

Further research by psychology researcher Christine Harris corroborated anecdotal evidence from dog owners, demonstrating that dogs exhibit jealousy when their owners direct attention towards other dogs. In her experiment, owners were instructed to ignore their dogs and instead lavish attention on either a pop-up book or a robotic dog toy that barked and wagged its tail. Blind video analysis revealed significantly more jealous behaviors (growling, snapping, pushing) when owners interacted with the robotic dog toy compared to the book. These jealous responses in dogs mirrored those observed in similar experiments with six-month-old human infants, suggesting a shared evolutionary basis for this complex social emotion.

Limits to Canine Intelligence: Understanding, Not Just Sensitivity

While dogs exhibit remarkable intelligence in social and emotional domains, it’s crucial to acknowledge the boundaries of their cognitive abilities. Their sensitivity to human cues, honed through millennia of co-evolution, might lead us to overestimate their overall intelligence. Dogs are exceptionally attuned to our actions, but their comprehension of the underlying meaning is not always complete. Canine cognition researcher Clive D. L. Wynne cautions against anthropomorphizing canine intelligence, stating, “It’s a happy accident that doggie thinking and human thinking overlap enough that we can have these relationships with dogs, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves that dogs are viewing the world the way we do.”

The “guilty look” often observed in dogs provides a compelling example of this distinction. Dog owners frequently interpret a dog’s demeanor upon returning home as an indication of guilt for misbehavior. However, research at Barnard’s Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab investigated this phenomenon. Dogs were left alone in a room with forbidden food and later greeted by their owners who were unaware of whether misbehavior had occurred. Rigorous video analysis revealed that “guilty” behaviors were primarily a response to owner chastisement, regardless of whether the dog had actually disobeyed. Dogs, in essence, are adept at reading and reacting to our emotional states, particularly disappointment, but this doesn’t necessarily equate to a human-like understanding of right and wrong. Their “guilt” is more likely rooted in their sensitivity to our displeasure rather than a moral compass.

In conclusion, dogs are undeniably intelligent creatures, particularly excelling in social cognition, emotional understanding, and communication with humans. They demonstrate abilities that rival, and in some cases surpass, those of other animals and even young children in specific domains. However, their intelligence is uniquely shaped by their evolutionary history and relationship with humans, and it’s essential to appreciate both their remarkable capabilities and the inherent differences between canine and human cognition. Dogs may not think exactly like us, but their unique intelligence enriches our lives in countless ways, forging deep bonds and offering a fascinating window into the diverse spectrum of intelligence in the animal kingdom.