How Many Men In The World Compared To Women is a captivating demographic question, exploring global gender distribution, which COMPARE.EDU.VN aims to illuminate. By examining sex ratios and their influencing factors, this analysis provides insights into population dynamics, offering clarity for anyone keen to understand gender balance and make informed decisions. Explore gender statistics and sex ratio trends on COMPARE.EDU.VN for valuable comparisons.

1. Understanding the Global Gender Ratio

The gender ratio, reflecting the proportion of males to females in a population, is a dynamic metric shaped by a complex interplay of biological, social, and economic factors. Globally, understanding this ratio provides valuable insights into demographic trends, societal norms, and potential disparities. Let’s explore the current state of the global gender ratio and the elements that contribute to its variations.

1.1. Current Global Statistics

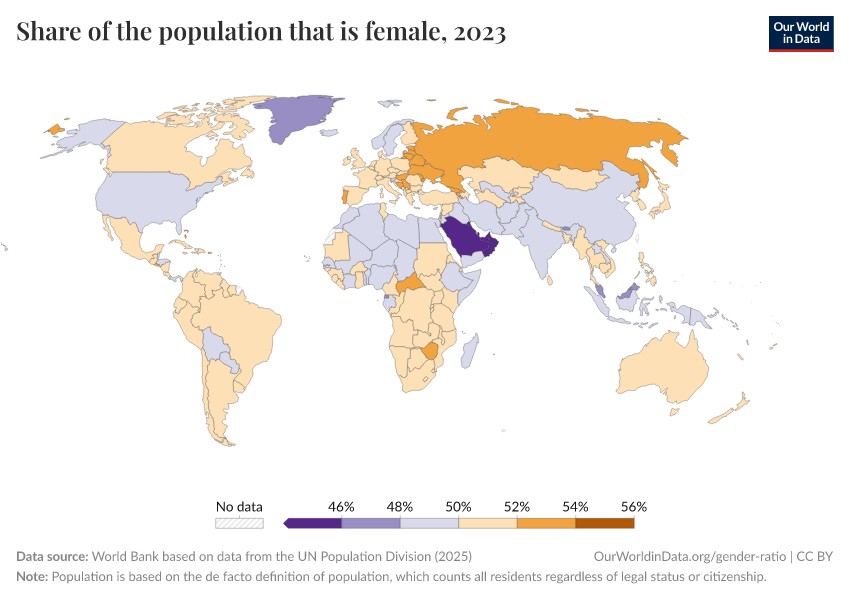

As of 2021, the global female share of the population is just under 50%. This may seem like a balanced distribution, but the sex ratio varies significantly across different regions and countries. The sex ratio is typically expressed as the number of males per 100 females. A ratio above 100 indicates more males than females, while a ratio below 100 indicates the opposite. These global statistics provide a general overview, but the nuances within different countries and age groups reveal more specific trends and factors.

1.2. Factors Influencing the Gender Ratio

The global gender ratio is not uniform; it is influenced by several key factors:

- Birth Rates: The sex ratio at birth is naturally male-biased, with approximately 105 males born for every 100 females. This biological phenomenon means that, initially, there are always more boys than girls.

- Mortality Rates: Women generally live longer than men due to a combination of biological and lifestyle factors. This difference in life expectancy means that, over time, the female population tends to increase relative to the male population.

- Migration Patterns: Immigration and emigration can significantly alter the gender ratio in specific regions. For example, countries with large numbers of male migrant workers often have a higher proportion of men in their population.

- Societal and Cultural Practices: In some regions, cultural preferences for male children have led to practices such as sex-selective abortions, which skew the gender ratio at birth.

1.3. Regional Variations

The global gender ratio varies significantly by region:

- Asia: Certain countries in South and East Asia, such as India and China, have historically exhibited lower female shares of the population due to son preference and sex-selective practices.

- Middle East: Some countries in the Middle East, like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, have a higher male share due to male-dominated immigration.

- Eastern Europe: Countries in Eastern Europe, including Russia, often have a higher female share due to significant sex gaps in life expectancy, with higher mortality rates among adult men.

Understanding these regional variations is essential for addressing specific demographic challenges and promoting gender equality.

2. Age-Specific Gender Ratios

The gender ratio varies significantly across different age groups, reflecting the influence of factors like birth rates, mortality, and societal practices. Examining these age-specific ratios provides a more detailed understanding of demographic dynamics.

2.1. Gender Ratio at Birth and in Childhood

The sex ratio at birth is typically male-biased, with around 105 males born for every 100 females. This ratio is consistent across most countries, driven by biological factors. However, in some regions, this natural bias is amplified due to cultural preferences for male children.

As children age, the gender ratio can shift due to varying mortality rates. Globally, boys tend to experience higher mortality rates in infancy and early childhood compared to girls. This means that although more boys are born, their numbers decrease slightly as they grow older.

2.2. Gender Ratio in Adulthood

In adulthood, the gender ratio continues to evolve, influenced by factors such as lifestyle, occupation, and health behaviors. Men often face higher risks of accidental deaths and occupational hazards, contributing to increased mortality rates. Additionally, behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption, which are sometimes more prevalent among men, can impact life expectancy.

By middle age (around 50 years), the gender ratio typically approaches parity, with roughly equal numbers of men and women. However, this balance begins to shift as age increases.

2.3. Gender Ratio in Older Age

In older age groups, the gender ratio becomes increasingly skewed towards women. Women tend to live longer than men due to a combination of genetic, hormonal, and lifestyle factors. This longevity leads to a higher proportion of women in older age brackets.

For example, among individuals aged 70 and older, there are significantly more women than men. In the oldest age bracket (100 years and older), the gender ratio can be as low as 24 men per 100 women.

2.4. Country-Specific Examples

To illustrate these age-specific variations, consider the following examples:

- Russia: The gender ratio declines sharply with age. By age 50, there are approximately 91 males per 100 females, and by age 70, this drops to around half as many men as women. This is largely due to high mortality rates among adult men.

- China and India: These countries have skewed gender ratios at birth and in early childhood due to son preference. However, as the population ages, the gender ratio shifts towards a higher proportion of women, though the initial imbalance persists to some degree.

- Developed Western Countries: These countries typically show a male-biased ratio at birth, a decline in early childhood due to higher male mortality, and an increasingly female-biased ratio in older age due to female longevity.

2.5. Implications of Age-Specific Gender Ratios

Age-specific gender ratios have significant implications for social policies, healthcare, and economic planning. Understanding these ratios helps in:

- Healthcare Planning: Addressing the specific health needs of different age groups, such as geriatric care for elderly women.

- Social Services: Tailoring social services to meet the needs of populations with varying gender ratios, such as support for elderly widows or employment programs for young men.

- Economic Policies: Developing policies that address potential labor market imbalances and support the economic contributions of different gender and age groups.

3. Biological Factors Affecting Gender Ratios

Several biological factors influence gender ratios, starting from conception through lifespan. Understanding these elements helps explain the natural variations and imbalances observed globally.

3.1. Sex Ratio at Conception

Research indicates that at conception, the sex ratio is approximately equal, meaning there are roughly the same number of male and female embryos conceived. A comprehensive study by Orzack et al. (2015) analyzed the sex ratio throughout pregnancy stages using various methods and found no significant difference in the number of males and females conceived.

3.2. Natural Male Bias at Birth

Despite an equal sex ratio at conception, births are typically male-biased. On average, there are about 105 male births for every 100 female births. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers this the “expected sex ratio at birth,” indicating a natural inclination towards more male births in the absence of gender discrimination or interference.

3.3. Factors Contributing to Male Bias

The shift from an equal sex ratio at conception to a male-biased ratio at birth is primarily due to differences in miscarriage rates during pregnancy. Several factors contribute to this:

- Early Pregnancy Risks: Male zygotes with chromosomal abnormalities have a higher probability of not surviving the first week of pregnancy.

- Mid-Pregnancy Risks: Female fetuses face a higher risk of mortality during the next 10-15 weeks of pregnancy.

- Late Pregnancy Risks: Around week 20, male and female mortality risks are approximately the same. Between weeks 28-35, male fetuses face a higher risk of mortality.

Overall, these varying risks result in a higher survival rate for male fetuses, leading to a male-biased sex ratio at birth.

3.4. Higher Mortality Rates in Boys

Even though more boys are born, they also experience higher mortality rates during infancy and childhood compared to girls. This phenomenon, often termed the “male disadvantage,” is influenced by several factors:

- Birth Complications: Boys are more prone to premature births, asphyxia, birth defects, and heart anomalies.

- Organ Immaturity: At birth, boys tend to have less physically mature organs and delays in physiological functions, such as lung function.

- Immune System Differences: Boys typically have a less developed immune system, making them more susceptible to infectious diseases. The Y chromosome in males contains fewer immune-related genes compared to the two X chromosomes in females, potentially weakening their immune response.

- Hormonal Effects: Higher levels of testosterone in males may inhibit immune system B and T-cells, while estrogen in females tends to enhance immune function.

These biological factors contribute to higher infant and child mortality rates in boys, partially offsetting the initial male bias at birth.

3.5. Female Longevity

Women generally live longer than men, a trend observed across most countries. The “female survival advantage” is attributed to a mix of genetic, hormonal, and lifestyle factors:

- Genetic and Hormonal Factors: The presence of two X chromosomes and the influence of estrogen are believed to provide women with a stronger immune system and better protection against cardiovascular diseases.

- Lifestyle Factors: Women are less likely to engage in risky behaviors like smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, which contribute to higher mortality rates in men.

This longevity leads to a higher proportion of women in older age groups, further skewing the overall gender ratio towards females as populations age.

4. Societal and Cultural Influences on Gender Ratio

Societal and cultural norms significantly influence gender ratios, sometimes leading to imbalances due to practices like sex-selective abortions and unequal treatment of genders.

4.1. Son Preference

In many regions, particularly in East and South Asia, a strong cultural preference for sons exists. This preference often stems from patrilineal traditions, where family lineage and property are passed down through the male line. Sons are often seen as more economically valuable, responsible for continuing the family name, and providing support for parents in old age.

4.2. Sex-Selective Practices

Son preference can lead to sex-selective practices, particularly prenatal sex selection, where parents use prenatal screening to determine the sex of the fetus and selectively abort female fetuses. The availability of technologies for prenatal sex determination has exacerbated this issue in countries like China, India, Vietnam, and Azerbaijan.

4.3. Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth

The impact of sex-selective practices is evident in the skewed sex ratios at birth in certain countries. For example, in China and India, the sex ratio at birth has been significantly higher than the natural expected ratio of 105 males per 100 females. This imbalance reflects deliberate efforts to ensure the birth of male children over female children.

4.4. Missing Women

Economist Amartya Sen first introduced the concept of “missing women” to describe the gap between the actual number of women in a population and the expected number if sex discrimination were absent. Missing women include those who are never born due to sex-selective abortions, as well as those who die prematurely due to neglect, infanticide, or unequal access to healthcare.

Estimates suggest that there are millions of missing women globally, primarily concentrated in countries with strong son preferences and sex-selective practices. These practices have far-reaching demographic and social consequences.

4.5. Historical Context of Infanticide

Infanticide, the deliberate killing of newborns, has a long history in human societies. While often associated with female infanticide, the practice has also targeted male infants in certain contexts. Historical records and anthropological studies reveal that infanticide has been practiced across various cultures and time periods, often driven by economic, social, or religious factors.

4.6. Unequal Treatment and Neglect

Even when female infants are not victims of infanticide, they may face unequal treatment and neglect compared to male children. This can include limited access to nutrition, healthcare, and education. Such disparities contribute to higher mortality rates among girls and women, further skewing the gender ratio.

4.7. Policy Interventions

Governments and organizations have implemented various policies to address the issue of skewed gender ratios and promote gender equality. These include:

- Banning Sex-Selective Abortions: Many countries have laws prohibiting prenatal sex determination and sex-selective abortions.

- Raising Awareness: Educational campaigns aim to challenge cultural norms that favor sons and promote the value of daughters.

- Economic Incentives: Some programs offer financial incentives to families who have daughters, encouraging them to value female children.

- Empowering Women: Initiatives that empower women through education, employment opportunities, and legal rights can help shift societal attitudes and reduce son preference.

While these policies have had some success, addressing deeply ingrained cultural norms and societal practices requires long-term, multi-faceted approaches.

4.8. Impact of Education and Economic Development

Education and economic development can play a complex role in influencing gender ratios. On one hand, increased education and income can empower women, reduce son preference, and improve access to healthcare. On the other hand, they can also increase access to technologies for prenatal sex determination, potentially exacerbating sex-selective practices.

The relationship between development and gender ratios is therefore not straightforward and requires careful consideration of cultural, economic, and social factors.

5. Consequences of Skewed Gender Ratios

Skewed gender ratios, resulting from practices such as sex-selective abortions and unequal treatment, have significant social, economic, and demographic consequences.

5.1. Marriage Imbalances

One of the most direct consequences of a skewed gender ratio is an imbalance in the marriage market. When there are significantly more men than women, many men may find it difficult or impossible to find a spouse. This can lead to a variety of social and psychological issues.

5.2. Delayed Marriage

In societies with skewed gender ratios, men may have to delay marriage due to the limited availability of potential partners. This can affect fertility rates and family structures, as men may have children later in life or not at all.

5.3. Increased Competition

A surplus of men can lead to increased competition for marriage partners, often disadvantaging men from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Women may “marry up,” leaving poorer men with fewer opportunities to find a spouse.

5.4. Social Instability

Some researchers hypothesize that skewed gender ratios can contribute to social instability and increased crime rates. The surplus of unmarried men, particularly those from marginalized communities, may lead to increased frustration and aggression. However, this link is complex and not fully understood.

5.5. Violence and Trafficking

In some regions, skewed gender ratios have been associated with increased violence against women and human trafficking. The scarcity of women can make them more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

5.6. Impact on Women

While it might seem that a shortage of women would increase their value, it can also lead to negative consequences. Women may face increased pressure to marry and have children early, limiting their educational and career opportunities. They may also be at greater risk of violence and coercion within marriage.

5.7. Family Lineage

In cultures where family lineage is passed down through males, a shortage of women can threaten the continuation of family names and traditions. This can create further pressure for families to prioritize having sons.

5.8. Economic Impacts

Skewed gender ratios can also have economic impacts. A shortage of women in the workforce can lead to labor shortages and reduced economic productivity. Additionally, the social and economic costs associated with addressing the negative consequences of gender imbalances, such as crime and violence, can be substantial.

5.9. Long-Term Demographic Effects

The demographic effects of skewed gender ratios can persist for generations. Imbalances in the sex ratio at birth can create a ripple effect, impacting the age structure of the population and leading to further social and economic challenges.

5.10. Global Examples

Countries like China and India, which have historically high sex ratios at birth, have faced many of these consequences. These include marriage squeezes, increased crime rates, and challenges related to social stability.

5.11. Addressing the Consequences

Addressing the consequences of skewed gender ratios requires a multi-faceted approach that includes:

- Promoting Gender Equality: Challenging cultural norms that favor sons and promoting the value of daughters.

- Enforcing Laws: Strict enforcement of laws against sex-selective practices and gender-based violence.

- Empowering Women: Providing women with equal access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities.

- Social Support: Offering support services for unmarried men and women to address the social and psychological challenges associated with gender imbalances.

6. Factors Affecting Gender Bias Strength

The strength of gender bias, particularly son preference, is influenced by various socioeconomic factors. Understanding these influences is crucial for developing effective strategies to address gender imbalances.

6.1. Income and Education

Contrary to common assumptions, higher income and education levels do not automatically reduce gender preference. In some cases, wealthier and more educated families may exhibit stronger son preference due to increased access to technology for sex selection.

6.2. Urban vs. Rural Areas

Gender bias can vary between urban and rural areas. Urban areas often have better access to prenatal screening and abortion services, potentially leading to higher rates of sex-selective abortions. However, rural areas may have stronger traditional beliefs that reinforce son preference.

6.3. Caste and Social Class

In some societies, caste and social class can influence gender bias. Higher castes or social classes may exhibit stronger son preference as a way to maintain family lineage and economic status.

6.4. Fertility Rates

Declining fertility rates can exacerbate gender bias. As families have fewer children, the pressure to have a son increases. This is often referred to as the “fertility squeeze.” In smaller families, the likelihood of having a son by chance is reduced, leading parents to resort to sex-selective practices.

6.5. Fertility Squeeze Explained

The “fertility squeeze” refers to the phenomenon where declining fertility rates intensify son preference. When families have multiple children, there is a higher probability that at least one will be a son. However, when families limit themselves to one or two children, the desire to ensure that at least one child is a son can lead to sex-selective abortions.

6.6. Evidence from India

Research in India has shown that declining fertility rates have contributed significantly to the skewed sex ratio. As families have fewer children, the preference for a son becomes more pronounced.

6.7. The Role of Development

Development can have both positive and negative effects on gender bias. Increased education and income can empower women and reduce son preference. However, development can also increase access to sex-selection technology and exacerbate the fertility squeeze.

6.8. Willingness, Ability, and Readiness

Sex-selective practices result from a combination of three factors:

- Willingness: The desire to have a child of a particular sex.

- Ability: Access to technology for prenatal sex determination and abortion services.

- Readiness: The willingness to act on the desire and ability to ensure the birth of a child of the preferred sex.

These three factors can change in different ways with development, education, and rising incomes.

6.9. Impact of Prenatal Practices Bans

Many countries have implemented bans on prenatal sex determination and sex-selective abortions. However, the effectiveness of these bans is debated. While they may prevent the situation from worsening, they often do not eliminate the practice entirely.

6.10. South Korea’s Example

South Korea implemented a ban on prenatal sex identification in the late 1980s. Initially, the sex ratio continued to increase after the ban. However, over time, the sex ratio has normalized, suggesting that a combination of policy interventions and changing social norms can be effective.

6.11. Policy Recommendations

Addressing gender bias requires a multi-pronged approach that includes:

- Promoting Gender Equality: Challenging cultural norms that favor sons and promoting the value of daughters.

- Enforcing Laws: Strict enforcement of laws against sex-selective practices and gender-based violence.

- Empowering Women: Providing women with equal access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities.

- Addressing the Fertility Squeeze: Implementing policies that support families and reduce the pressure to have sons.

By understanding the complex factors that influence gender bias, policymakers can develop more effective strategies to promote gender equality and address the consequences of skewed gender ratios.

7. Conclusion

Understanding the global gender ratio and its influencing factors is crucial for addressing demographic imbalances and promoting gender equality. From biological determinants to societal practices, a variety of elements shape the distribution of men and women across the world.

7.1. Key Takeaways

- Global Variations: The gender ratio varies significantly across regions and age groups, influenced by birth rates, mortality, migration, and cultural practices.

- Biological Factors: Natural male bias at birth and differences in mortality rates between boys and girls play a significant role in shaping gender ratios.

- Societal Influences: Son preference and sex-selective practices lead to skewed gender ratios in certain countries, resulting in millions of missing women.

- Consequences: Skewed gender ratios have far-reaching social, economic, and demographic consequences, including marriage imbalances, social instability, and violence.

- Policy Interventions: Addressing gender imbalances requires a multi-faceted approach that includes promoting gender equality, enforcing laws against sex-selective practices, and empowering women.

7.2. Future Trends

As societies continue to develop and social norms evolve, gender ratios are likely to shift. Increased access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities for women can help reduce son preference and promote gender equality. However, ongoing monitoring and policy interventions are needed to address emerging challenges and ensure balanced demographic outcomes.

7.3. Call to Action

It is essential for governments, organizations, and individuals to work together to promote gender equality and address the root causes of skewed gender ratios. This includes challenging cultural norms that favor sons, supporting initiatives that empower women, and ensuring that all members of society have equal opportunities to thrive.

7.4. Compare and Decide with COMPARE.EDU.VN

For more in-depth comparisons and information on demographic trends, visit COMPARE.EDU.VN. Our platform provides detailed analyses and resources to help you compare and decide on a wide range of topics, including global gender ratios.

7.5. Contact Information

For inquiries and further information, please contact us at:

- Address: 333 Comparison Plaza, Choice City, CA 90210, United States

- WhatsApp: +1 (626) 555-9090

- Website: COMPARE.EDU.VN

By understanding the complexities of gender ratios and working towards gender equality, we can create a more equitable and prosperous world for all.

8. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

-

What is the global gender ratio?

- The global gender ratio is approximately balanced, with slightly fewer than 50% of the population being female as of 2021. However, this ratio varies significantly by region and age group.

-

Why are there more boys born than girls?

- Biologically, there is a natural male bias at birth, with about 105 males born for every 100 females. This is due to differences in miscarriage rates during pregnancy.

-

Why do women generally live longer than men?

- Women tend to live longer than men due to a combination of genetic, hormonal, and lifestyle factors. They often have stronger immune systems and are less likely to engage in risky behaviors.

-

What is son preference?

- Son preference is a cultural preference for male children, often stemming from patrilineal traditions where family lineage and property are passed down through the male line.

-

What are sex-selective practices?

- Sex-selective practices are actions taken to ensure the birth of a child of a particular sex, often involving prenatal screening and selective abortion of female fetuses.

-

What are “missing women”?

- “Missing women” refers to the gap between the actual number of women in a population and the expected number if sex discrimination were absent, including those who are never born due to sex-selective abortions and those who die prematurely due to neglect or unequal treatment.

-

How does declining fertility rates affect gender ratios?

- Declining fertility rates can exacerbate gender bias. As families have fewer children, the pressure to have a son increases, leading to sex-selective practices.

-

What are the consequences of skewed gender ratios?

- Skewed gender ratios can lead to marriage imbalances, social instability, increased crime rates, and violence against women.

-

What can be done to address skewed gender ratios?

- Addressing gender imbalances requires promoting gender equality, enforcing laws against sex-selective practices, empowering women, and challenging cultural norms that favor sons.

-

How can I find more information about gender ratios?

- Visit COMPARE.EDU.VN for detailed analyses and resources on demographic trends, including global gender ratios.

Remember to visit compare.edu.vn at 333 Comparison Plaza, Choice City, CA 90210, United States, or contact us via WhatsApp at +1 (626) 555-9090.