At the heart of our solar system lies the Sun, a colossal star that dwarfs everything in its vicinity. When we think about the Sun, words like ‘big’ or ‘large’ often come to mind, but to truly grasp its immensity, it’s essential to understand just how big the sun is compared to Earth. This isn’t just a slight difference; it’s a scale that’s almost mind-boggling.

The Sun isn’t just the largest object in our solar system; it utterly dominates it. Holding a staggering 99.8% of the solar system’s total mass, the Sun’s diameter is approximately 109 times that of Earth. Imagine lining up 109 Earths in a row – that’s roughly the width of the Sun. In terms of volume, about one million Earths could comfortably fit inside the Sun. This gives you a first glimpse into the truly immense scale we’re talking about when comparing the Sun to our home planet.

But size isn’t the only extreme characteristic of the Sun. Its surface temperature blazes at around 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius), while the core reaches an unimaginable 27 million degrees Fahrenheit (15 million degrees Celsius) due to ongoing nuclear reactions. To put the Sun’s energy output into perspective, NASA estimates it would take 100 billion tons of dynamite exploding every single second to match the energy the Sun produces.

The Sun is just one of over 100 billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy. It resides about 25,000 light-years from the galactic center and completes an orbit around it roughly every 250 million years. Our Sun is considered a relatively young star, belonging to a generation known as Population I stars, which are characterized by a higher abundance of elements heavier than helium.

The Birth of Our Star: How the Sun Formed

The Sun’s story began approximately 4.6 billion years ago. Scientists believe it, along with the rest of our solar system, originated from a vast, swirling cloud of gas and dust called the solar nebula. As gravity caused this nebula to collapse, it began to spin faster and flatten into a disk shape. The majority of the material was drawn towards the center of this spinning disk, eventually igniting and forming the Sun.

The Sun is currently in a stable phase of its life, fueled by nuclear fusion. It has enough fuel to maintain its current state for another 5 billion years. However, this stellar lifespan isn’t indefinite. In its later stages, the Sun will dramatically expand into a red giant, engulfing the inner planets. Eventually, it will shed its outer layers, leaving behind a dense core that will cool and fade into a white dwarf, and finally, theoretically, into a black dwarf over an immense timescale.

Inside the Sun: Structure and Atmosphere

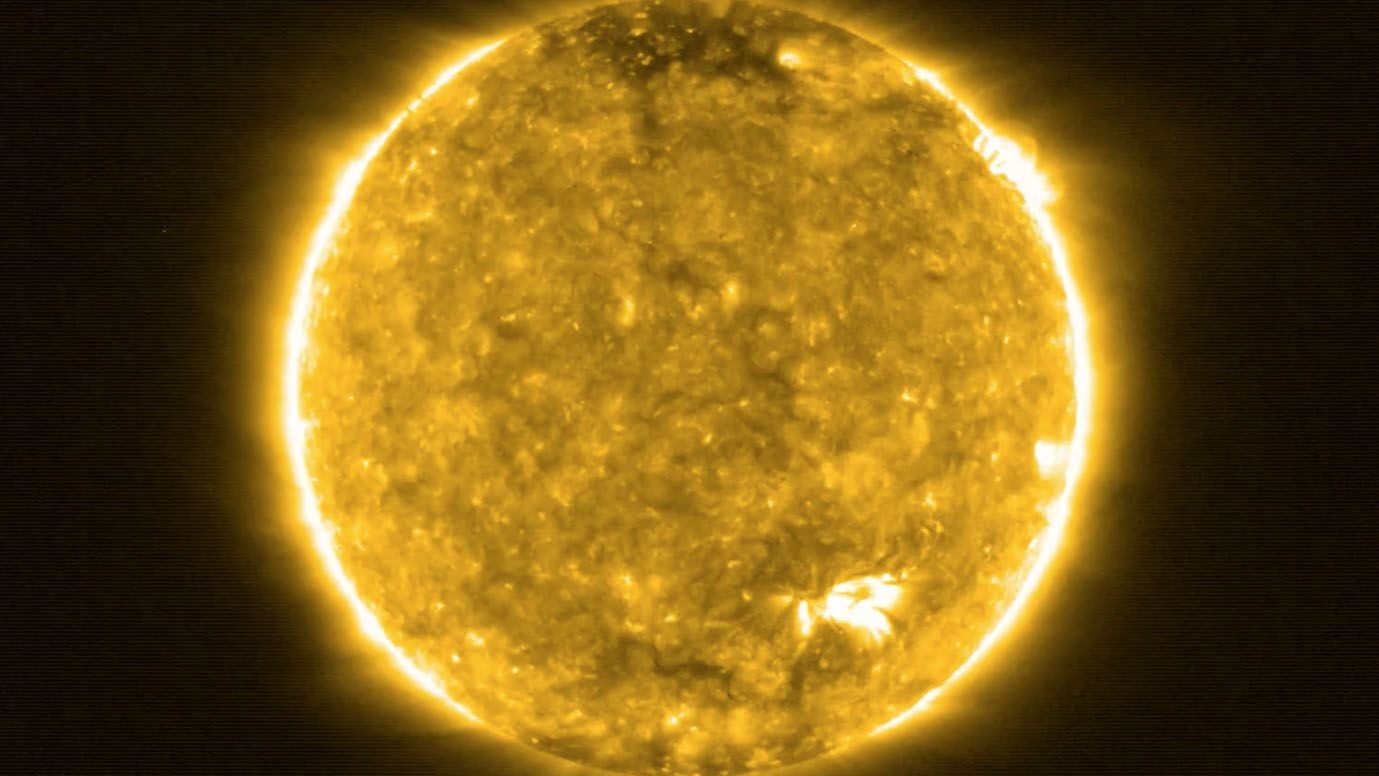

The Sun isn’t a uniform ball of gas; it has a distinct internal structure and a layered atmosphere. Moving from the Sun’s interior outwards, we encounter the core, the radiative zone, and the convective zone. Above this lies the solar atmosphere, comprised of the photosphere, chromosphere, a transition region, and the corona. Extending far beyond is the solar wind, a constant stream of particles emanating from the corona.

The core, despite making up only about 2% of the Sun’s total volume, contains nearly half of its mass and is incredibly dense – about 15 times denser than lead. Surrounding the core is the radiative zone, accounting for 32% of the Sun’s volume and 48% of its mass. Energy from the core travels through this zone as radiation, a process so slow that a single photon can take a million years to traverse it.

The convective zone, reaching up to the Sun’s visible surface, constitutes the majority of the Sun’s volume (66%) but only a small fraction of its mass (just over 2%). This zone is characterized by turbulent “convection cells” of gas, including granulation cells and larger supergranulation cells.

The photosphere is the Sun’s visible surface, the lowest layer of its atmosphere, and the source of the light we see. It’s relatively thin, about 300 miles (500 km) thick, with temperatures ranging from 11,000 F (6,125 C) at the bottom to 7,460 F (4,125 C) at the top. Above the photosphere lies the chromosphere, hotter at up to 35,500 F (19,725 C) and composed of spiky structures called spicules.

The transition region, a few hundred to a few thousand miles thick, separates the chromosphere from the corona and is heated by the corona above it, emitting significant ultraviolet radiation. The outermost layer, the corona, is incredibly hot, ranging from 900,000 F (500,000 C) to over 10.8 million F (6 million C), and can reach even higher temperatures during solar flares. The corona is the source of the solar wind, a continuous outflow of charged particles into space.

The Sun’s Dynamic Magnetic Field

The Sun possesses a magnetic field, typically only twice as strong as Earth’s overall magnetic field. However, in localized areas, this field can become intensely concentrated, reaching up to 3,000 times stronger. This magnetic complexity arises from the Sun’s differential rotation – it spins faster at its equator than at its poles – and the fact that its interior rotates faster than its surface.

These magnetic field distortions are responsible for many dynamic solar phenomena, including sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections. Solar flares are the most powerful explosions in our solar system, releasing immense amounts of energy. Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are less violent but involve the ejection of vast quantities of solar material into space – a single CME can expel billions of tons of matter.

What the Sun is Made Of: Chemical Composition

Like most stars, the Sun is primarily composed of hydrogen, followed by helium. The remaining fraction consists of trace amounts of other elements, predominantly oxygen, carbon, neon, nitrogen, magnesium, iron, and silicon. For every million hydrogen atoms in the Sun, there are approximately 98,000 helium atoms, 850 oxygen atoms, 360 carbon atoms, and so on. Despite hydrogen being the lightest element, it accounts for about 72% of the Sun’s mass, while helium makes up around 26%.

Sunspots and the Solar Cycle

Sunspots are darker, cooler regions on the Sun’s surface. They appear where concentrated magnetic field lines from the Sun’s interior pierce through the photosphere.

The number of sunspots visible on the Sun changes cyclically, reflecting variations in solar magnetic activity. This cycle, known as the solar cycle, averages about 11 years. It ranges from a minimum with few or no sunspots to a maximum with up to 250 sunspots or sunspot groups, and then back to a minimum. At the end of each cycle, the Sun’s magnetic field reverses its polarity.

A History of Observing Our Star

Humans have observed the Sun for millennia. Ancient civilizations tracked its movement to mark seasons, create calendars, and predict eclipses. For a long time, a geocentric model, placing Earth at the center of the universe, prevailed. However, in 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus proposed a heliocentric model with the Sun at the center. Galileo Galilei’s observations in 1610 further supported this model.

Modern solar observation advanced significantly with the space age. NASA’s Orbiting Solar Observatory program, starting in 1962, provided crucial data in ultraviolet and X-ray wavelengths. The Ulysses probe, launched in 1990, studied the Sun’s polar regions. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), launched in 1995, has been a groundbreaking mission, contributing immensely to our understanding of the solar wind, solar interior, and space weather forecasting.

The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), launched in 2010, continues to provide unprecedented detail of solar activity. Currently, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe and ESA/NASA’s Solar Orbiter, launched in 2018 and 2020 respectively, are pushing the boundaries of solar exploration by orbiting closer to the Sun than ever before. Parker Solar Probe ventures directly into the Sun’s corona, while Solar Orbiter captures the closest-ever images of the Sun’s surface. These missions are revolutionizing our understanding of the Sun and its influence on our solar system.

In conclusion, the Sun is not just a large star; it is a celestial giant compared to Earth, a powerhouse of energy, and a dynamic object that continues to fascinate and challenge scientists. Understanding how big the sun is compared to Earth is the first step in appreciating the Sun’s fundamental role in our solar system and its profound influence on our planet.