Ever since Galileo Galilei, a pioneer of observational astronomy, turned his self-designed telescope towards the heavens in 1610, Jupiter has captivated scientists and stargazers alike. This gas giant, the undisputed heavyweight champion of our Solar System, continues to present mysteries even after centuries of scrutiny and numerous exploratory missions. Its sheer scale and dramatically different nature compared to our home planet, Earth, underscore the incredible diversity found within our cosmic neighborhood.

One of the most fundamental aspects that sets Jupiter apart is its size. For us Earth-dwellers, accustomed to the dimensions of our terrestrial world, grasping the immensity of Jupiter can be challenging. From its colossal volume and mass to its unique composition and the dynamics of its magnetic and gravitational fields, Jupiter forces us to reconsider our planetary norms. Its impressive retinue of moons further highlights the complexity and grandeur of this gas giant. Understanding just how big Jupiter is compared to Earth is the first step in appreciating the truly remarkable nature of this celestial behemoth.

Size, Mass, and Density: A Colossal Contrast

To truly appreciate the size disparity, let’s delve into the numbers. Earth, our familiar home, has a mean radius of 6,371 kilometers (3,958.8 miles). Its mass clocks in at a substantial 5.97 × 1024 kilograms. Now, consider Jupiter. This giant boasts a mean radius of a staggering 69,911 ± 6 kilometers (43,441 miles) and a mass of 1.8986 × 1027 kilograms.

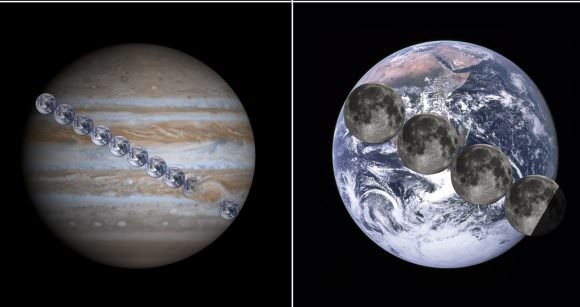

In simpler terms, Jupiter’s radius is approximately 11 times that of Earth. Imagine lining up eleven Earths side-by-side to span the radius of Jupiter – that’s the scale of difference we’re talking about. When it comes to mass, Jupiter is just under 318 times more massive than Earth. It would take almost 318 Earths to equal the mass of this single gas giant.

However, density tells a different story. Earth, being a terrestrial planet composed of rock and metal, is significantly denser than Jupiter. Earth’s density is 5.514 grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm³), whereas Jupiter, primarily composed of lighter gases, has a density of only 1.326 g/cm³. This lower density, despite its immense size, is a key characteristic of gas giants.

This difference in density also impacts surface gravity. While Jupiter doesn’t have a solid surface in the traditional sense, we can consider the gravitational force at the point in its atmosphere where the pressure is equivalent to Earth’s sea-level atmospheric pressure (1 bar). At this level, Jupiter’s gravitational force is approximately 24.79 meters per second squared (m/s²), which is about 2.528 times Earth’s surface gravity (9.8 m/s² or 1 g). If you could stand on Jupiter at this atmospheric level (hypothetically, of course, without being crushed by pressure or burned by heat), you would weigh over two and a half times your weight on Earth!

Size comparison of Jupiter and Earth, illustrating the immense scale difference between the gas giant and our terrestrial planet. Image credit: NASA/SDO/Goddard/Tdadamemd

Composition and Structure: Worlds Apart

The fundamental building blocks of Earth and Jupiter are vastly different. Earth is a terrestrial planet, built from silicate minerals and metals. Its internal structure is differentiated into a metallic core, a silicate mantle, and a crust. The core itself is further divided into a solid inner core and a liquid outer core, the latter playing a crucial role in generating Earth’s magnetic field. As you descend from the crust towards the Earth’s center, both temperature and pressure escalate dramatically. Earth’s shape is an oblate spheroid, slightly flattened at the poles and bulging at the equator due to its rotation.

Jupiter, in stark contrast, is a gas giant, composed predominantly of hydrogen and helium in gaseous and liquid states. It lacks a defined solid surface. Its outer atmosphere is primarily hydrogen (88–92%) and helium (8–12%) by volume, translating to roughly 75% hydrogen and 24% helium by mass, with trace amounts of other elements making up the remaining percentage.

This atmosphere, while seemingly thin compared to the planet’s overall size, is incredibly dynamic. It contains trace amounts of methane, water vapor, ammonia, and silicon-based compounds, as well as hydrocarbons like benzene and other elements such as carbon, ethane, hydrogen sulfide, neon, oxygen, phosphine, and sulfur. Interestingly, crystals of frozen ammonia have been observed in the outermost layers of Jupiter’s cloud decks.

Diagram illustrating Jupiter’s internal structure and composition, highlighting the layers of molecular hydrogen, metallic hydrogen, and the potential rocky core. Image Credit: Kelvinsong CC by S.A. 3.0

Jupiter’s denser interior, beneath the gaseous atmosphere, is estimated to be about 71% hydrogen, 24% helium, and 5% other elements by mass. Scientists believe that deep within Jupiter lies a core of dense materials, possibly rocky, although its exact nature remains uncertain. Surrounding this core is a massive layer of liquid metallic hydrogen, a state of hydrogen achieved under immense pressure, along with some helium. Further outwards, this transitions into a layer predominantly composed of molecular hydrogen.

Similar to Earth, temperature and pressure within Jupiter increase dramatically as you descend towards the core. At the “surface” (1 bar pressure level), the temperature is around 340 Kelvin (67 °C, 152 °F) and the pressure is 10 bars. Deeper down, in the region where hydrogen becomes metallic, temperatures are estimated to reach a scorching 10,000 K (9,700 °C; 17,500 °F) and pressures a colossal 200 Gigapascals (GPa). At the core boundary, temperatures may soar to 36,000 K (35,700 °C; 64,300 °F), with interior pressures reaching a staggering 3,000–4,500 GPa.

Like Earth, Jupiter is also an oblate spheroid, but its flattening at the poles is significantly more pronounced (0.06487 ± 0.00015 compared to Earth’s 0.00335). This greater oblateness is a direct consequence of Jupiter’s incredibly rapid rotation, which causes its equatorial radius to be approximately 4,600 kilometers larger than its polar radius.

Orbital Parameters: Paths Around the Sun

Earth’s orbit around the Sun is nearly circular, with a small eccentricity of about 0.0167. Its distance from the Sun varies from 147.095 million kilometers (0.983 Astronomical Units or AU) at perihelion (closest approach) to 151.93 million kilometers (1.015 AU) at aphelion (farthest point). The average distance, the semi-major axis, is approximately 149.598 million kilometers, defining one Astronomical Unit (AU).

Earth completes one orbit around the Sun in approximately 365.25 days, defining a year. This orbital period necessitates leap years to keep our calendar aligned with the seasons. While a solar day is 24 hours, Earth’s sidereal rotation (rotation relative to distant stars) is slightly shorter at 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds. Earth’s axial tilt of 23.4° relative to its orbital plane (the ecliptic) is responsible for our planet’s seasons, creating variations in temperature and sunlight distribution across hemispheres throughout the year.

The orbits of the inner planets, including Earth, and the position of Jupiter in the outer Solar System, illustrating the vast distance separating them and the asteroid belt in between. Credit: Wikipedia Commons

Jupiter orbits the Sun at a much greater average distance of 778.299 million kilometers (5.2 AU), ranging from 740.55 million kilometers (4.95 AU) at perihelion to 816.04 million kilometers (5.455 AU) at aphelion. At this distance, Jupiter takes a significantly longer time to orbit the Sun – 11.86 Earth years, or 4,332.59 Earth days, for a single Jovian year.

Despite its longer orbital period, Jupiter boasts the fastest rotation of all planets in our Solar System. It completes one rotation on its axis in just under 10 hours (9 hours, 55 minutes, and 30 seconds). Therefore, a Jovian year, while lasting almost 12 Earth years, contains a staggering 10,475.8 Jovian solar days. This rapid rotation is a major factor in Jupiter’s oblate shape and its dynamic atmospheric features.

Atmospheres: Layers of Gas and Storms

Earth’s atmosphere is a relatively thin but vital envelope of gases, structured into five main layers: the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere. Air pressure and density generally decrease with altitude, though temperature variations within these layers are more complex. The troposphere, the lowest layer, contains about 80% of the atmosphere’s mass and almost all of its water vapor, making it the region where most weather phenomena occur. Earth’s atmosphere is primarily composed of nitrogen (78%) and oxygen (21%), with trace amounts of other gases.

Jupiter’s atmosphere, vastly different in scale and composition, is also layered, though the layering is based more on cloud decks and pressure levels than distinct temperature zones like Earth’s. As mentioned earlier, it is primarily hydrogen and helium. Like Earth, Jupiter experiences auroras near its poles, but these Jovian auroras are far more intense and persistent, driven by the planet’s powerful magnetic field and volcanic material from its moon Io.

Jupiter’s banded atmosphere, showcasing zones and belts created by differential rotation and convection, along with the iconic Great Red Spot. Credit: NASA

Jupiter is renowned for its extreme weather. Winds in its zonal jets routinely reach speeds of 100 meters per second (360 km/h), and can gust up to 620 km/h (385 mph). Storms on Jupiter can form rapidly and grow to thousands of kilometers in diameter overnight. The most famous of these storms is the Great Red Spot, a colossal anticyclonic storm that has raged for at least 350 years. While the Great Red Spot has been observed to shrink and expand over time, it remains a dominant feature of Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Jupiter is perpetually shrouded in clouds, primarily composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. These clouds are arranged in bands of different latitudes, known as tropical regions, and are located in the tropopause. The cloud layer is relatively shallow, about 50 km (31 miles) deep, and likely consists of multiple decks of clouds with varying densities. Evidence suggests that a layer of water clouds may exist beneath the ammonia clouds, indicated by lightning activity in Jupiter’s atmosphere, which can be up to a thousand times more powerful than lightning on Earth.

Composite images from the Chandra X-Ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope show the hyper-energetic x-ray auroras at Jupiter. Credit: NASA/CXC/UCL/W.Dunn et al/STScI

Moons: A Solitary Moon vs. a Lunar System

Earth has a single, relatively large natural satellite, the Moon. Its presence has been known since prehistory, and it has profoundly influenced human culture, mythology, and astronomy. The Moon exerts a significant tidal force on Earth and has been a focal point for scientific exploration, being the only celestial body beyond Earth where humans have walked. The prevailing theory of the Moon’s formation is the giant-impact hypothesis, suggesting it formed from debris ejected after a collision between Earth and a Mars-sized object named Theia in the early Solar System.

An artistic illustration depicting Jupiter and its four largest moons, the Galilean satellites: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Credit: NASA

Jupiter, in contrast, possesses a vast and complex system of moons, currently numbering 95 confirmed moons and moonlets. The four largest, the Galilean moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – discovered by Galileo, are each fascinating worlds in their own right. Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System; Europa is a prime candidate for harboring a subsurface ocean and potentially life; Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System and the only moon known to have its own magnetic field; and Callisto, also possibly harboring a subsurface ocean, has an ancient, heavily cratered surface.

Beyond the Galilean moons, Jupiter hosts an inner group of small moons (Metis, Adrastea, Amalthea, and Thebe) and a vast population of irregular satellites, which are smaller, more distant, and have eccentric orbits. These irregular moons are thought to be captured asteroids or fragments from collisions. Jupiter’s moon system is more akin to a miniature solar system in itself compared to Earth’s single lunar companion.

Conclusion: A Tale of Two Worlds

In almost every aspect – size, mass, composition, atmosphere, and moon systems – Earth and Jupiter represent fundamentally different types of planets. Jupiter, a gas giant of immense proportions, dwarfs our terrestrial home in scale, mass, and atmospheric dynamism. While Earth offers a habitable, rocky world with a single moon, Jupiter presents a swirling, stormy sphere of gas and liquid with a complex system of dozens of moons. Understanding the stark contrast between these two planets highlights the incredible diversity and range of planetary bodies within our Solar System and the wider universe. The ongoing exploration of Jupiter, particularly by missions like NASA’s Juno, continues to unveil new secrets and deepen our appreciation for this giant among planets.