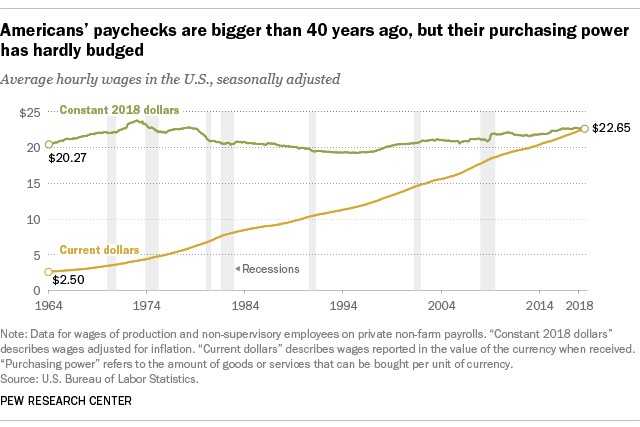

Despite a booming job market and historically low unemployment rates, many American workers are not experiencing the wage growth one might expect. While the U.S. unemployment rate hovers near a two-decade low and employers have consistently added jobs for years, wage increases have not kept pace with economic recovery, leaving many wondering why their paychecks aren’t reflecting the positive economic indicators. In fact, after adjusting for inflation, the average American worker’s wage today has roughly the same purchasing power it did four decades ago. This disconnect between a seemingly thriving labor market and stagnant real wages raises critical questions about the economic realities for the average worker.

Average hourly earnings have seen modest nominal growth, but when we consider the impact of inflation, the picture becomes less optimistic. In July, average hourly earnings for non-management private-sector workers stood at $22.65, a 2.7% increase year-over-year. While consistent with the average growth of the past five years, this rate pales in comparison to periods before the 2007-08 financial crisis, where annual wage growth often reached around 4%. Looking further back to the high-inflation era of the 1970s and early 1980s, wage increases were even more substantial, frequently jumping by 7%, 8%, or even 9% annually. However, these nominal increases from decades past don’t tell the whole story when considering the significant role of inflation over time.

When we adjust for inflation, using constant dollars to reflect real purchasing power, the stagnation becomes strikingly clear. The average hourly wage today buys roughly the same amount as it did in 1978. This is after a period of decline in the 1980s and early 1990s, followed by inconsistent growth. In real terms, average hourly earnings actually peaked over 45 years ago. The $4.03 hourly wage in January 1973 had the equivalent purchasing power of $23.68 today, highlighting the erosion of real wage growth over the decades. Similarly, an analysis of “usual weekly earnings” for full-time wage and salary workers reinforces this trend. While median weekly earnings have increased in current dollars since 1979, in inflation-adjusted terms, they have barely increased, demonstrating a long-term stagnation in real wage growth for American workers.

Adding to the complexity, wage growth has not been evenly distributed across the income spectrum. The majority of wage gains in recent decades have flowed disproportionately to the highest earners, exacerbating income inequality. Since 2000, real weekly wages for the lowest earners have seen minimal growth, while those in the top tenth of the earnings distribution have experienced significantly larger percentage increases in their real wages. This divergence means that while the top earners are benefiting from economic growth, a significant portion of the workforce is seeing little to no improvement in their real earnings, contributing to a widening gap between the highest and lowest paid workers.

While wages are the most visible part of employee compensation, benefits also play a crucial role. However, even when considering benefits, the overall picture of compensation for the average worker remains concerning. Benefit costs, including health insurance and retirement contributions, have risen faster than wages in recent years. This rise in benefit costs may be one factor constraining employers’ ability or willingness to significantly increase cash wages. Data shows that total benefit costs for civilian workers have risen substantially more than wage and salary costs since the early 2000s, suggesting a shift in the composition of employee compensation that may not translate into increased take-home pay for workers.

Economists and analysts have pointed to several potential factors contributing to this prolonged wage stagnation. The decline of labor union membership has weakened workers’ collective bargaining power, potentially limiting wage growth. Educational attainment in the U.S. lagging behind other developed countries could also be a factor, impacting the skills and earning potential of the workforce. Furthermore, the increased use of noncompete clauses and other restrictions on job mobility may limit workers’ ability to seek higher wages by switching jobs. The presence of a large pool of potential workers outside the formal labor force could also exert downward pressure on wages. Finally, the shift in employment from higher-wage manufacturing and production sectors to lower-wage service industries has fundamentally altered the wage landscape.

The persistent stagnation of real wages has significant implications, including its contribution to widening income inequality in the United States. Data reveals a substantial increase in the ratio of income between the top tenth and bottom tenth of earners over the past few decades. This growing income gap underscores the uneven distribution of economic gains and highlights the challenges faced by many American workers in achieving meaningful financial progress despite overall economic growth. Understanding the multifaceted reasons behind wage stagnation is crucial for developing effective policies to promote broader economic prosperity and ensure that the benefits of economic growth are more equitably shared among all workers.