The European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, individual EU member states often implement their own climate policies, creating overlaps with the ETS. This raises a crucial question: Does The Ets Compare Student Country Wide, or how effective are these overlapping policies in actually reducing emissions across the EU? This article delves into the complexities of overlapping climate policies, examining their impact on emissions reduction and exploring the concept of “climate effectiveness.”

alt text: graph showing effective emissions reduction rate

alt text: graph showing effective emissions reduction rate

Understanding Internal Carbon Leakage and the Waterbed Effect

Two key concepts are crucial to understanding the impact of overlapping policies: internal carbon leakage and the waterbed effect. Internal carbon leakage occurs when a policy in one country simply shifts emissions to another country within the ETS, resulting in no overall reduction. Imagine a country phasing out coal power plants but then importing electricity generated from coal in a neighboring country. This scenario demonstrates 100% internal carbon leakage.

The waterbed effect describes how a reduction in emissions in one sector, due to a specific policy, can lead to increased emissions in other sectors within a fixed-cap system like the ETS. Lower demand for allowances in one area can lower the carbon price, incentivizing increased emissions elsewhere. The EU ETS, however, utilizes a Market Stability Reserve (MSR) that adjusts the allowance supply, mitigating the waterbed effect to some extent.

Calculating Climate Effectiveness

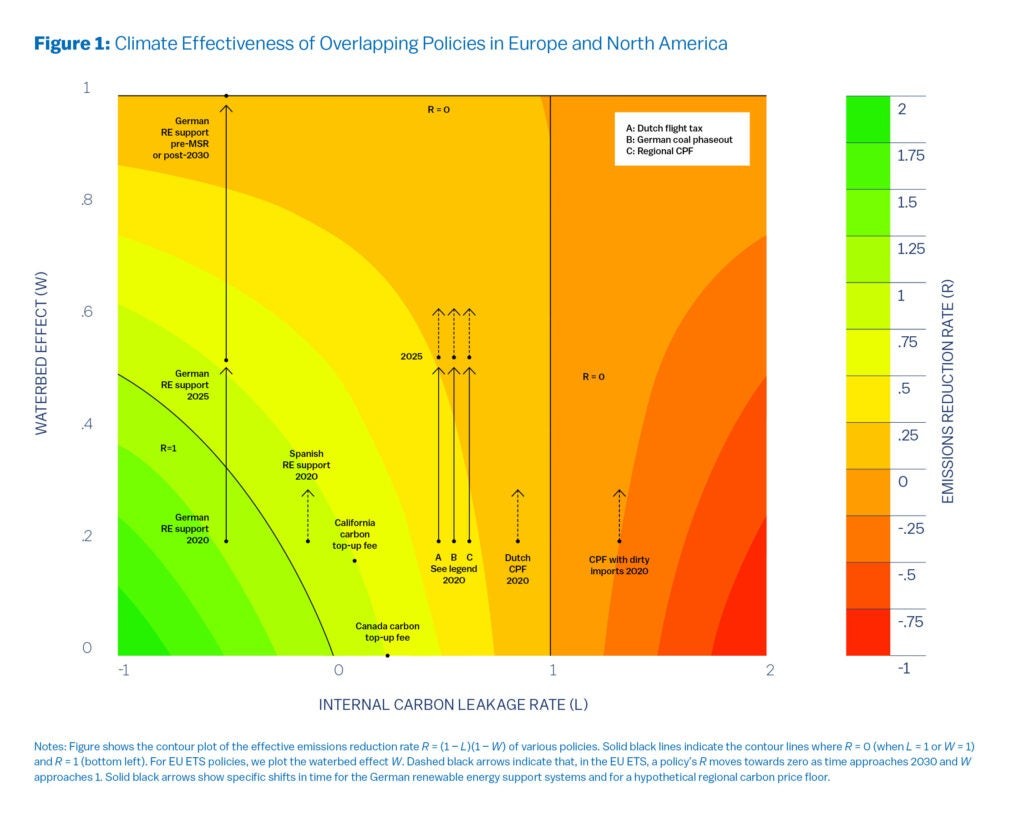

A policy’s true climate effectiveness depends on its direct emissions reduction, the degree of internal carbon leakage (L), and the magnitude of the waterbed effect (W). A simple formula captures this relationship:

Effective Emissions Reduction = Direct Emissions Reduction (1 – L) (1 – W)

This formula helps determine the effective emissions reduction rate (R). A policy can be truly complementary (R > 1) if it triggers further emissions reductions elsewhere, or it can backfire (R < 0) if it leads to increased overall emissions.

Policy Types and Their Leakage Potential

Policies that restrict the supply of high-emission products (e.g., carbon taxes, production limits) tend to have high leakage rates. Conversely, policies that reduce demand for these products (e.g., promoting renewables, energy efficiency) often exhibit negative leakage, meaning they can reduce emissions beyond the targeted sector. This happens because lower demand can decrease prices, making cleaner alternatives more competitive across the region.

Examples of Overlapping Policies in the EU

The article examines several real-world examples:

- Carbon Price Floors: National carbon price floors can have limited effectiveness due to high leakage, especially in smaller, interconnected countries.

- Coal Phase-Outs: While aiming to reduce emissions, coal phase-outs can experience significant leakage if replaced by imported electricity from dirtier sources.

- Aviation Taxes: Aviation taxes often suffer from high leakage as air travel shifts to neighboring countries without such taxes.

- Renewable Energy Support: Support for renewable energy often leads to negative leakage, as it reduces electricity prices and displaces dirtier generation sources across the region. This demonstrates how a policy in one country can positively impact overall EU emissions.

Conclusion: Considering Policy Design and Interactions

Overlapping climate policies present a complex challenge. Their effectiveness hinges on careful policy design, accounting for potential leakage and the interactions with the broader ETS framework. A simple formula considering leakage and the waterbed effect can offer valuable insights for policymakers evaluating the true impact of their climate actions. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for achieving meaningful emissions reductions across the EU and answering the question of whether and how the ETS compare student country wide in its impact. The key takeaway is that simply focusing on national emissions reductions can be misleading; a comprehensive analysis of system-wide effects is essential for effective climate action.