Understanding the evolution of language requires a deep dive into the intricate relationship between language and social cognition. While language is unique to humans, many of its underlying mechanisms are shared with other species. By comparing these mechanisms across different species, we can gain insights into which aspects of human language are truly unique and which have evolutionary roots in our animal ancestors. This comparative approach is central to the work of Tecumseh Fitch, a leading researcher in the field of biolinguistics. While this article doesn’t directly quote Fitch’s beliefs, it explores core concepts central to his research, allowing us to infer his likely stance on modern and comparative viewpoints.

The Intertwined Nature of Language and Social Cognition

Social cognition, encompassing abilities like social learning, imitation, and theory of mind, is crucial for language acquisition. Children rely on sophisticated social cues to infer word meanings and communicate effectively. Conversely, language enhances social cognition, enabling complex cultural transmission and knowledge accumulation. This reciprocal relationship suggests a co-evolutionary process where advancements in one domain fueled progress in the other.

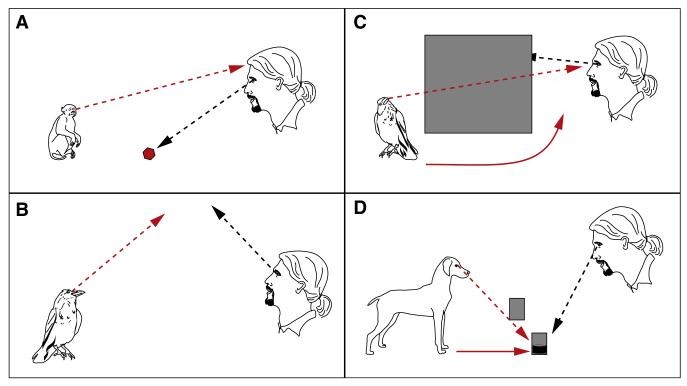

Fitch likely believes that dissecting the components of social cognition, like gaze following and theory of mind, is crucial to understanding the building blocks of language. As the article details, gaze following has varying levels of complexity, from simple gaze detection to geometric gaze following behind barriers. The presence of these abilities in diverse species like dogs, goats, and ravens indicates that these components might be more ancient and widespread than previously thought. Similarly, research on theory of mind in primates and corvids suggests that understanding others’ knowledge states, while perhaps not as complex as in humans, might have deeper evolutionary roots.

The Role of Convergence in Evolutionary Studies

The article emphasizes the importance of convergent evolution, where similar traits arise independently in unrelated species due to similar environmental pressures. Convergent evolution provides strong evidence for the adaptive significance of a trait. For instance, the ability of both humans and honeybees to communicate about displaced objects highlights the adaptive value of this communicative feature in specific ecological contexts.

Fitch, as a proponent of the comparative approach, likely sees convergent evolution as a powerful tool for testing hypotheses about the evolution of language. By studying species like ravens, which face similar challenges to early hominids in scavenging for food, researchers can investigate whether similar communicative pressures led to the evolution of complex communication systems. The article highlights how ravens’ use of vocalizations and roosts as information centers could be studied to test specific hypotheses about the emergence of displacement in language.

Vocal Learning and Cultural Transmission

Vocal learning, the ability to acquire vocalizations through imitation, is a key component of language. Birdsong, with its cultural transmission and regional dialects, offers a compelling parallel to human language. The article describes how songbirds learn their songs through a process involving innate predispositions, environmental input, and vocal practice, mirroring the development of human speech.

Fitch probably recognizes the crucial role of vocal learning in language evolution and likely values birdsong as a valuable model system. The article’s discussion of babbling in human infants and subsong in birds, along with the phenomenon of cultural transmission and even a “ratchet effect” in birdsong, underscores the parallels between these two communication systems. These similarities allow researchers to explore fundamental questions about the neural and genetic mechanisms underlying vocal learning, providing potential insights into the evolution of human speech.

Beyond Vocal Imitation: Emulation and Innovation

The article highlights that social learning extends beyond imitation to include emulation, where individuals learn about the effects of actions on the environment. Keas, for instance, can learn to solve complex problems by observing others, even without directly imitating their actions.

Fitch likely appreciates the broader context of social learning and acknowledges that emulation and innovation play significant roles in cultural evolution. The article’s discussion of selectivity in social learning, where individuals choose what, when, and from whom to learn, further emphasizes the complexity of this process. The ability to rationally imitate, demonstrated in infants, chimpanzees, and dogs, points to the sophisticated cognitive processes involved in cultural transmission.

Conclusion

While we cannot definitively state Tecumseh Fitch’s beliefs without directly quoting him, the core principles discussed in the article strongly align with the comparative approach that characterizes his work. He likely champions the study of diverse species, recognizing the value of both homologous and analogous traits in reconstructing the evolutionary history of language. By studying social cognition, vocal learning, and cultural transmission in a wide range of animals, researchers can continue to refine our understanding of the evolutionary journey that ultimately led to the unique phenomenon of human language. The research outlined in this article, focusing on diverse species and encompassing behavioral, neural, and genetic levels of analysis, embodies the kind of comprehensive approach that Fitch likely advocates for unraveling the mysteries of language evolution.