Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate and compare the image quality and radiation exposure of Gemstone Spectral Imaging (GSI) with rapid kV switching technology against conventional polychromatic imaging (CPI) in abdominal CT examinations.

Methods:

Adult patients referred for abdominal CT scans between October 2015 and March 2016 were included in this study. Patients underwent an unenhanced CT scan using CPI mode and a tri-phase (arterial, portal, and delayed phase) contrast-enhanced scan using GSI mode, each with distinct protocols. Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined in muscle and fat tissues. We compared parametric image quality metrics—noise, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and clinical image quality—between monochromatic images reconstructed at 65 keV from GSI and conventional polychromatic images. Radiation dose levels for CPI and GSI were also compared.

Results:

The study included 43 patients. Compared to conventional imaging, noise levels in GSI images were generally similar in the arterial and portal phases but were approximately 10% higher in the delayed phase. The SNR in the portal phase of GSI was significantly superior to CPI, while SNR was comparable between arterial/delayed phases and CPI. Clinical image quality was largely consistent between CPI and GSI. GSI resulted in a dose length product reduction of 0.3–20.1% compared to CPI.

Conclusion:

GSI offers a slight reduction in radiation exposure while maintaining or even enhancing image quality in abdominal CT scans. These findings support the potential application of GSI for patients requiring abdominal CT imaging.

Advances in knowledge:

This study demonstrates that in abdominal CT, GSI achieves a modest reduction in radiation exposure without compromising image quality, and in some aspects, even improves it compared to CPI. These findings advocate for the broader adoption of GSI in abdominal CT imaging practices.

Introduction

Gemstone spectral imaging (GSI), a recent advancement incorporating dual-energy fast kVp-switching technology, has facilitated the commercialization of dual-energy CT.1 GSI employs a single X-ray tube to generate two sets of polychromatic X-rays, typically at 80 and 140 kVp, in rapid succession, acquiring near-simultaneous paired images from virtually identical perspectives.2 These high- and low-kVp images are then processed into material density maps for a selected material pair (water and iodine). From these maps, virtual monochromatic images are derived.3 In comparison to conventional polychromatic imaging (CPI), the current standard, GSI has the potential to offer reduced noise and improved contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR),4–7 alongside richer data sets including virtual monochromatic images, spectral curves, and iodine mapping. These additional features hold significant promise for enhancing the diagnosis and evaluation of various diseases.8 For instance, in abdominal and pelvic CT scans, which constitute over 30% of all CT scans performed in the United States in 2006,9 GSI could provide supplementary quantitative metrics to refine lesion differentiation compared to CPI. Research by Yang et al. has indicated that quantitative iodine concentration measurements can improve the assessment of microvascular invasion in small hepatocellular carcinomas.10 Furthermore, Mileto et al. have shown that monochromatic spectral images can mitigate renal cyst pseudo-enhancement within the 80–140 keV energy range.11 Additionally, water density images could serve as a lower radiation dose alternative to true unenhanced images.12

As CT imaging becomes more prevalent, concerns about the potential risks associated with radiation exposure are increasingly important. Efforts must focus on achieving “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) radiation doses while ensuring adequate image quality for accurate clinical diagnoses. Several studies investigating GSI in abdominal CT have reported superior image quality compared to CPI.6, 13,14 A recent study demonstrated radiation dose reduction with enhanced image quality when comparing GSI with adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction (ASIR) to CPI in abdominal CT for patients with high body mass index.15 However, to our knowledge, direct comparisons of radiation dose and image quality between conventional CT and GSI within the same patient cohort undergoing abdominal CT remain limited. Therefore, this study aimed to compare image quality, specifically noise, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), clinical image quality scores, and radiation exposure, between abdominal GSI scans and CPI scans in the same patients.

Methods and Materials

Patients

This study received ethical approval from the relevant ethics committee, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to undergoing scans. Between October 2015 and March 2016, adult patients referred for clinically indicated upper abdominal CT scans (navel to diaphragm) or abdominal CT scans (diaphragm to lower edge of symphysis pubis) were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were: age over 18 years, no known hypersensitivity to iodine contrast agents, and non-pregnancy.

Scan protocol

All patients underwent a plain scan [unenhanced phase (UEP)] using CPI mode and a tri-phase contrast-enhanced scan using GSI mode on a Discovery 750HD CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). Following the UEP scan, intravenous contrast medium (Iopromide, Ultravist 300, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin-wedding, Germany) was administered at a dose of 450 mg kg–1 using a power injector at a rate of 3 ml s−1. Enhanced scanning with GSI mode was performed in three phases: arterial phase (AP), portal phase (PP), and delayed phase (DP), with delay times of 30 s, 60 s, and 180 s post-contrast injection, respectively. Consistent parameters across all four phases included: pitch of 0.984, section thickness of 0.625 mm, matrix of 512 × 512, field of view (FOV) of 35 cm, and reconstruction thickness of 5 mm. For the unenhanced CPI scan (UEP), the tube potential was set to 120 kVp, and the tube current was determined by the noise index (NI), set at 10. The enhanced GSI scans (AP, PP, and DP) utilized fast kVp-switching between 80 kVp and 140 kVp (GSI mode) with varying tube current (mA) settings: AP, maximum mA value from the UEP; PP, mA setting based on the automatic spectral imaging protocol selection technique, designed to personalize patient dose by optimizing spectral imaging protocol selection,16 with a target NI of 10; and DP, mean mA [(maximum + minimum)/2] from the UEP. A detailed summary of scanning parameters is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scan protocol

| Scanning Parameters | CPI (unenhanced scan) | GSI (enhanced scan) |

|---|---|---|

| Tube voltage (kVp) | 120 | 80 and 140 |

| Tube current (mA) | ||

| UEP | (defined by NI of 10, 150~400 mA) | |

| AP | 400 | |

| PP | (defined by NI of 10) | |

| DP | 275 | |

| Gantry rotation time (s) | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Pitch | 0.984:1 | 0.984:1 |

| FOV (cm) | 35 | 35 |

| Matrix | 512 × 512 | 512 × 512 |

| Delay time (s) | ||

| AP | 30 | |

| PP | 60 | |

| DP | 180 | |

| Flow rate (ml s−1) | N/A | 3 |

| Contrast dose (mg Kg−1) | N/A | 450 |

| Section thickness (mm) | 0.625 | 0.625 |

| Reconstruction thickness (mm) | 5 | 5 |

AP, arterial phase; CPI, conventional polychromatic imaging; DP, delayed phase; FOV, field of view; GSI, gemstone spectral imaging; NI, noise index; PP, portal phase; UEP, unenhanced phase.

All CT images were reconstructed using the filtered back projection (FBP) technique. A monochromatic energy level of 65 keV is the standard setting in our hospital for abdominal CT due to evidence suggesting it provides optimal diagnostic image quality.17, 18 Therefore, for GSI mode, monochromatic images at 65 keV were reconstructed for subsequent image quality comparisons.

Assessment of image quality and radiation exposure

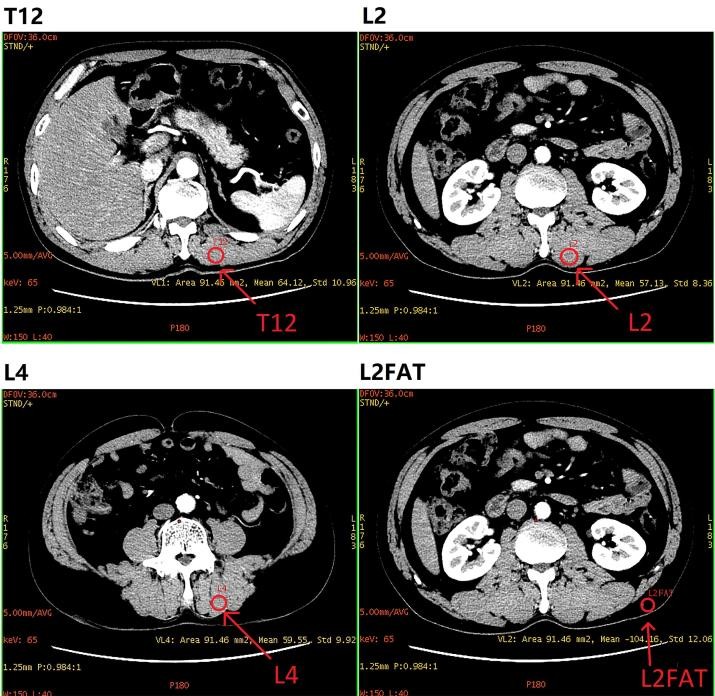

To ensure objective and quantitative image quality assessment, two experienced radiologists, blinded to the image data and scan type, independently drew regions of interest (ROIs) by consensus using Advantage Workstation (v. 4.6; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). ROIs were standardized in size (approximately 91 mm2) and window width/level. Circular ROIs were positioned in four locations within the anterior abdominal wall: three in the erector spinae muscle (lumbar vertebrae L2 and L4, and thoracic vertebrae T12) and one in the abdominal fat at lumbar vertebrae L2 (Figure 1). Each ROI type was measured three times at different sites, and the average parameter values were calculated. Objective image quality in muscle and fat was chosen for comparison because it is less influenced by contrast media compared to organs like the aorta, thereby providing a more consistent measure. The standard deviation of CT numbers (in Hounsfield units, HU) within each ROI was recorded as the objective image noise. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was calculated using the formula:

Figure 1.

ROIs positioned on arterial phase images from the same patients. Circular ROIs were placed in the anterior abdominal wall, including three in the erector spinae muscle (lumbar vertebrae L2, L4, and thoracic vertebrae T12) and one in abdominal fat at lumbar vertebrae L2. ROIs, regions of interest.

| SNR = CT number / SD |

|---|

where CT number represents the mean CT value within the ROI, and SD (standard deviation) represents the mean objective image noise.

To investigate the impact of contrast media on SNR, a separate experiment was conducted with four patients who underwent plain scans (UEP) and tri-phase contrast-enhanced scans on the same Discovery 750HD CT scanner. Both unenhanced and enhanced phases were performed using GSI mode with identical scanning protocols as detailed in Table 1. ROIs were drawn as described above, with each ROI type measured three times at different sites. Objective image noise and SNR were compared between each enhanced phase and the UEP using a paired Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05.

Clinical image quality was independently evaluated by two radiologists with 17 and 10 years of experience in abdominal CT interpretation. Subjective image noise, artifacts, anatomical structure clarity, and overall image quality were assessed using a 5-point scale, as outlined in Table 2. The average scores from both radiologists were used for clinical image quality assessment.

Table 2.

Grading scale for clinical image quality

| Score | Image noise | Artifacts | Anatomical structure | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Minimum | Minimum | Clear | Superior |

| 4 | Less than average | Partial artifacts, not affecting diagnosis | Better than average, not very clear | Above average |

| 3 | Average | Artifacts in the whole body, but diagnosis still possible | Average | Average |

| 2 | Above average | Artifacts affecting diagnosis | Poorer than average | Suboptimal |

| 1 | Unacceptable | Unacceptable | Very Poor | Unacceptable |

Radiation exposure was quantified using dose-length product (DLP) data from the dose report generated after each scan phase. CT dose index (CTDI) values were not used as the primary metric because scan lengths can vary between patients, leading to variations in DLP even with identical CTDI values. The CTDI values of the scanner are routinely validated by medical physicists at Panyu Central Hospital as part of standard quality assurance procedures.

Statistical analysis

Inter-observer agreement for clinical image quality assessments was evaluated using kappa statistics. Kappa values were interpreted as follows: less than 0.20, poor; 0.21 to 0.40, fair; 0.41 to 0.60, moderate; 0.61 to 0.80, substantial; and 0.81 to 1.00, almost perfect.19, 20 CT number, objective image noise, SNR, clinical image quality scores, and DLP for each enhanced phase were compared to the UEP using paired Student’s t-tests. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 43 patients were enrolled (29 male, 14 female), with a mean age of 51.7 years (range 24–88 years, standard deviation 14.7 years). Diagnostic indications included hepatic cyst, renal cyst, hepatic hemangioma, nephrolithiasis, cholecystitis, and gallstone.

Objective image quality

Detailed results for CT number, image noise, and SNR comparisons are presented in Table 3. CT numbers for muscle and fat were generally significantly higher in all three enhanced GSI phases (AP, PP, and DP) compared to the unenhanced CPI phase (UEP). Noise levels were generally similar between UEP and AP, and between UEP and PP. However, significantly higher noise levels (approximately 10%) were observed in DP compared to UEP in both fat and muscle ROIs. SNR in the PP of the enhanced scan was significantly higher than in the UEP, while SNR was generally comparable between AP/DP and UEP. The effect of contrast on SNR calculation is summarized in Table 4, indicating no significant differences in objective image quality between unenhanced and enhanced phases in terms of noise and SNR.

Table 3.

Comparison of CT number, noise, SNR between CPI and GSI in the CT

| ROI | CT number (HU) | Noise | SNR |

|---|---|---|---|

| L2 Muscle | L2 FAT | L4 Muscle | |

| UEP | |||

| Mean (SD) | 54.31 (8.55) | −95.28 (17.45) | 57.33 (7.89) |

| AP | |||

| Mean (SD) | 57.37 (8.90) | −97.95 (17.69) | 58.32 (9.17) |

| p-value | 0.003[a](#t3_fn4) | *<*0.001 | 0.185 |

| PP | |||

| Mean (SD) | 62.85 (9.38) | −96.49 (19.22) | 63.44 (9.44) |

| p-value | *<*0.001 | 0.319 | *<*0.001 |

| DP | |||

| Mean (SD) | 64.41 (8.75) | −94.60 (20.76) | 65.92 (8.49) |

| p-value | *<*0.001 | 0.484 | *<*0.001 |

AP, arterial phase; CPI, conventional polychromatic imaging; DP, delayed phase; GSI, gemstone spectral imaging; HU, Hounsfield unit; Noise, objective image noise (standard deviation of CT numbers in an ROI); PP, portal phase; ROI, region of interest; SD, standard deviation of noise; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; UEP, unenhanced phase.

L2 Muscle, erector spinae muscle at the lumbar vertebrae level L2; L2 FAT, fat at the level of lumbar vertebrae L2; L4 Muscle, erector spinae muscle at the lumbar vertebrae level L4; T12 Muscle = erector spinae muscle at the thoracic vertebrae level T12.

a p-values highlighted in italic and bold indicate significance in paired Student t-tests between noise in unenhanced phase and arterial, portal, or delayed phases. p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 4.

The comparison of objective image quality between unenhanced phase and enhanced phase with GSI model

| Comparison | p-value of Noise | p-value of SNR |

|---|---|---|

| UEP-AP | 0.942 | 0.156 |

| UEP-PP | 0.347 | 0.145 |

| UEP-DP | 0.239 | 0.056 |

GSI, gemstone spectral imaging; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; UEP-AP, comparison between unenhanced phase and arterial phase, UEP-PP, comparison between unenhanced phase and portal phase; UEP-DP, comparison between unenhanced phase and delayed phase.

Clinical image quality

Inter-observer agreement between the two radiologists for clinical image quality scores ranged from moderate to almost perfect (κ = 0.256–0.890). Percentage agreement ranged from 76.7% (33/43) to 97.7% (42/43), as detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Percentage agreement and Kappa coefficient (κ) between clinical image quality scores of CPI and GSI determined by two radiologists

| Image quality | UEP | AP | PP | DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noise | Agreement | 93% (40/43) | 81.4% (35/43) | 90.7% (39/43) |

| κ | 0.677 | 0.604 | 0.652 | |

| Artifacts | Agreement | 95.3% (41/43) | 93.0% (40/43) | 90.7% (39/43) |

| κ | 0.890 | 0.831 | 0.719 | |

| Anatomical structure | Agreement | 90.7% (39/43) | 88.4% (38/43) | 93% (40/43) |

| κ | 0.452 | 0.256 | 0.377 | |

| Overall image quality | Agreement | 93% (40/43) | 79.1% (34/43) | 97.7% (42/43) |

| κ | 0.860 | 0.625 | 0.879 |

AP, arterial phase; CPI, conventional polychromatic imaging; DP, delayed phase; GSI, gemstone spectral imaging; PP, portal phase; UEP, unenhanced phase.

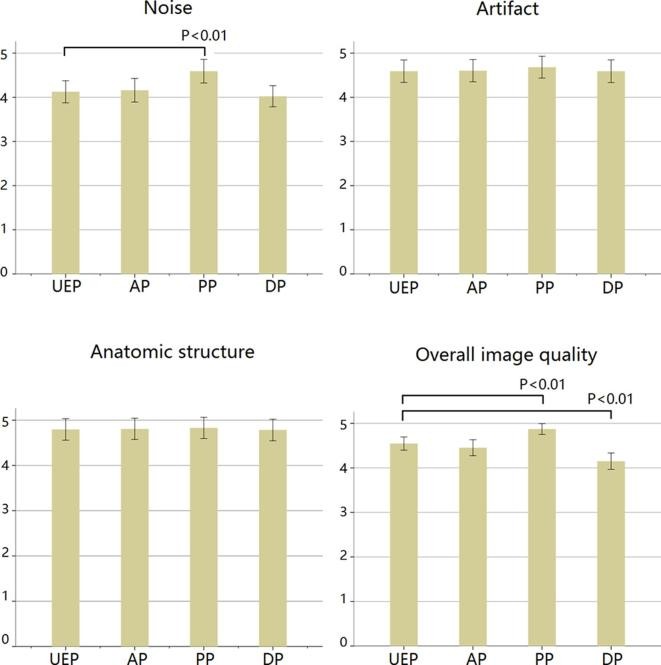

Clinical image quality scores are summarized in Figure 2. Most comparisons showed no significant difference in clinical image quality between CPI and the three GSI phases. However, PP image quality was rated superior to UEP in terms of subjective image noise and overall image quality. Conversely, overall image quality in DP was rated worse than UEP.

Figure 2.

Comparison of clinical image quality scores between GSI and CPI modes in abdominal CT. PP scores were significantly higher than UEP scores for subjective image noise and overall image quality, while DP overall image quality was significantly lower than UEP (all p < 0.01). CPI, conventional polychromatic imaging; GSI, gemstone spectral imaging.

Radiation Dose

DLPs for all four phases are presented in Table 6. Compared to UEP with CPI mode (400.6 ± 213.5 mGycm), DLPs were reduced in GSI scans: AP (383.9 ± 190.3 mGycm) by 4.2%, PP (399.4 ± 192.4 mGycm) by 0.3%, and DP (320.0 ± 138.5 mGycm) by 20.1%. Reductions in AP and PP were not statistically significant, but the reduction in DP was significant (p < 0.001). Although the NI was set to 10 for both PP and UEP, slight dose variations (0.3%) occurred due to differences in tube voltages.

Table 6.

Comparisons of radiation exposure between conventional imaging and rapid kV switching dual-energy imaging in abdomen CT

| Parameter | UEP | AP | PP | DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean scan length/mm | 213.7 | 213.7 | 213.7 | 213.7 |

| DLP range/mGycm | 123.3–1036.6 | 196.8–930.0 | 195.6–954.3 | 196.8–683.4 |

| DLP Mean (SD)/mGycm | 400.6 (213.5) | 383.9 (190.3) | 399.4 (192.4) | 320.0 (138.5) |

| DLP Reduction/% | – | −4.2% | −0.3% | −20.1% |

| p-value | – | 0.194 | 0.810 | *<*0.001[a](#t6_fn5) |

AP, arterial phase; DP, delayed phase; DLP, dose length product (in mGycm); PP, portal phase; SD, standard deviation; UEP, unenhanced phase.

ReductionX, ( MeanX – MeanUEP)/ MeanUEP ×100% (MeanX is the mean value of phase X).

a p-value highlighted in italic and bold indicates significance in paired Student t-test between DLPs in unenhanced phase and arterial, portal, or delayed phases. p-value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that GSI scans at 65 keV, derived from fast kVp-switching spectral CT, generally maintain both objective and subjective image quality compared to conventional polychromatic 120-kVp images. This is achieved with comparable or lower radiation doses in patients undergoing routine abdominal CT examinations using CPI mode. These findings align with previous research. One study reported reduced image noise in 70 keV monochromatic images compared to 120-kVp images at equivalent radiation doses during the same abdominal CT scan.6 Zhu et al. also indicated that GSI and ASIR can achieve comparable image quality with reduced radiation dose compared to conventional scan protocols.15 However, Zhu et al.’s study did not compare images from the same patients. Our results, by comparing doses within the same patient group, suggest that implementing GSI in clinical practice is viable, offering more information and comparable image quality with potentially lower radiation exposure.

Image quality versus dose performance is influenced by both patient size and the X-ray spectrum.21 Our intra-individual comparison minimizes the effect of patient size. The X-ray spectrum is primarily determined by the tube current-time product and tube voltage. Traditional CT uses polychromatic X-rays, where low-energy X-rays can cause beam hardening artifacts and degrade image quality.22 In GSI mode, fast kVp-switching technology alternates projections between two different polychromatic spectra of 80 kVp and 140 kVp every 0.2 milliseconds.2 Exposures at 80 kVp are typically longer than at 140 kVp.23 Consequently, the average kVp in GSI mode in our study was less than 110 kVp, lower than the 120 kVp used in CPI mode. Average tube current in GSI was higher in AP and lower in DP compared to UEP (Table 1). In PP scans, the NI was empirically set to 10, as in UEP, based on prior studies,24, 25 to determine the tube current product. Lowering tube current-time product or tube voltage reduces radiation dose but may increase image noise, and vice versa. This relationship partially explains the significantly lower dose in DP. However, the enhanced GSI scans maintained or improved image quality compared to UEP. Monochromatic images from GSI scans are known to reduce beam hardening artifacts.26 Therefore, despite comparable or lower radiation exposure, GSI mode can maintain image quality in monochromatic images.

For image quality comparison, we used enhanced CT scans with GSI and unenhanced imaging with CPI. Direct comparison between enhanced and unenhanced images might be considered inappropriate. To mitigate this, we selected ROIs in fat and muscle, where contrast enhancement is minimal (Figure 1). Our experiment (Table 4) indicated that SNR with GSI is not significantly affected by contrast. While small enhancements in fat and muscle, evident in CT number variations (Table 3), might introduce minor errors in noise comparison, performing two separate scans (GSI and CPI) in each patient solely for comparison purposes, particularly when not diagnostically necessary, is ethically problematic for radiation protection. An alternative approach, comparing two patient groups (one with GSI and one with CPI), introduces unfairness due to inter-patient variability.

We opted not to evaluate CNR in this study, focusing on CT values, image noise, and SNR for objective image quality. Accurate CNR comparison requires comparable absolute CT values in both GSI and CPI scans. This condition was not met in our study for liver and abdominal aorta ROIs because GSI images were enhanced while CPI scans were unenhanced, resulting in non-comparable “contrast” in CNR.

In our GSI analysis, we used monochromatic images at 65 keV. While justified by existing evidence, different keV levels can influence image quality metrics. Cui et al. reported superior image quality with 70 keV monochromatic images compared to CPI in abdominal CT,27 and Lv et al. found noise levels in 50–70 keV monochromatic images to be similar or lower than CPI images.16 Different monochromatic energy level selections can yield varying quantitative image quality assessments. However, the image quality differences between 60/70 keV and 65 keV are unlikely to significantly alter our overall conclusions.

Our study has limitations. The sample size of 43 patients is relatively small, potentially limiting statistical power. Larger studies are needed to confirm these findings. ROI placement may influence quantitative parameter calculations, hence we performed triple measurements for each ROI. Variance analysis showed that CT number and noise variations were within 5% and 10% of mean values, respectively, suggesting acceptable error levels with multiple ROIs and averaging. Our study lacked specific diagnostic task assessments. Future studies incorporating specific diagnostic tasks would provide more clinically relevant information. Finally, all images were reconstructed using FBP, not ASIR, which could further reduce image noise. Our clinic primarily uses combined ASIR-FBP reconstruction, but the ASIR ratio varies between unenhanced and enhanced scans. To ensure fair GSI and CPI mode comparison, we used FBP reconstruction exclusively.

Conclusions

Utilizing tailored protocols in GSI scans, monochromatic spectral images at 65 keV in clinical abdominal CT maintain image quality comparable to conventional polychromatic images, with similar or slightly reduced radiation exposure. Our findings contribute to the growing evidence base supporting the application of GSI in routine clinical abdominal CT imaging.

Footnotes

The authors Tianqi Fang and Wei Deng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Tianqi Fang, Email: [email protected].

Wei Deng, Email: [email protected].

Martin Wai-Ming Law, Email: [email protected].

Liangping Luo, Email: [email protected].

Liyun Zheng, Email: [email protected].

Ying Guo, Email: [email protected].

Hanwei Chen, Email: [email protected].

Bingsheng Huang, Email: [email protected].

REFERENCES

[1] Johnson TRC, Fink C, Schönberg SO, Reiser MF. Dual-energy CT in clinical practice. Br J Radiol. 2007 Dec;80 Spec No 1:S76-84. doi: 10.1259/bjr/27758788. PubMed PMID: 18238909.

[2] যন্ত্র CT 750 HD [Internet]. GE Healthcare. [cited 2017 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www3.gehealthcare.com/en/products/categories/computed_tomography/ct-scanners/discovery-ct750-hd

[3] Alvarez RE, Macovski A. Energy-selective reconstructions in X-ray computerized tomography. Phys Med Biol. 1976 Jul;21(5):733-44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/21/5/002. PubMed PMID: 961749.

[4] Karimzadeh MA, Tauchert M, Frellesen C, Ackermann H, Hentschel M, Rogalla P, et al. Image quality of dual-energy CT with fast kVp switching (GSI) in comparison to standard single-energy CT: phantom and clinical studies. Eur J Radiol. 2010 Dec;76(3):e139-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.09.003. Epub 2009 Oct 9. PubMed PMID: 19819040.

[5] Fletcher JG, Yu L, McCollough CH. Dose reduction in CT: current technology and future directions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012 May;198(5):W482-95. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7435. PubMed PMID: 22539677.

[6] Hidas G, So CB, Peteani F, Mileto A, Nelson R, Marin D, et al. Virtual monochromatic dual-energy CT images at 70 keV optimize image quality in routine abdominal CT: a phantom study and clinical experience. Eur Radiol. 2013 May;23(5):1420-7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2718-1. Epub 2012 Dec 13. PubMed PMID: 23238684.

[7] Boas FE, Thomas C, Schaefer-Prokop C. Virtual monochromatic spectral imaging with fast kVp switching dual-energy CT: optimization of keV settings for pulmonary nodule evaluation. Radiology. 2013 Oct;269(1):247-53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122530. Epub 2013 Jun 12. PubMed PMID: 23757494.

[8] Apfaltrer P, Sudarski S, Tataru MC, Fingerle AA, Stroszczynski C, Sommer WH. Added value of dual-energy CT in abdominal imaging. Radiologe. 2015 Aug;55(8):629-38. doi: 10.1007/s00117-015-2897-3. German. PubMed PMID: 26183554.

[9] Fazel R, формально DM, Чен J, Goldman L, Ting HH, Spertus JA, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 6;361(9):849-57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0901249. PubMed PMID: 19710483.

[10] Yang Z, Wang K, Zhou X, Chen H, Liu F, Zeng M, et al. Added value of iodine concentration measurement with dual-energy spectral CT for evaluating microvascular invasion of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2015 Aug;25(8):2354-63. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3622-4. Epub 2015 Mar 6. PubMed PMID: 25740509.

[11] Mileto A, Nelson RC, первичный D, первичный D, Marin D, первичный D, et al. Renal cyst pseudoenhancement: virtual monochromatic spectral images from rapid kVp-switching dual-energy CT can help. Radiology. 2013 Sep;268(3):888-95. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122531. Epub 2013 Jun 12. PubMed PMID: 23757493.

[12] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Water-only images from dual-energy CT: image quality and radiation dose compared with true unenhanced images in phantoms and humans. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012 Jul;199(1):105-11. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7994. PubMed PMID: 22723390.

[13] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Dual-energy CT of the abdomen with gemstone spectral imaging: image quality optimization for virtual monochromatic series. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Jul;197(1):W42-8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5908. PubMed PMID: 21700941.

[14] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Dual-energy CT of the abdomen with gemstone spectral imaging: radiation dose considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Jul;197(1):W49-55. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5909. PubMed PMID: 21700942.

[15] Zhu Z, Wang Z, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Gemstone spectral imaging and adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction allow for radiation dose reduction without compromising image quality in obese patients undergoing abdominal CT. Eur J Radiol. 2013 Dec;82(12):e820-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.07.001. Epub 2013 Jul 27. PubMed PMID: 23911454.

[16] Lv P, Yu C, Zhang J, Cheng L, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Image quality and radiation dose of gemstone spectral imaging and conventional single-energy imaging for liver CT examination. Eur J Radiol. 2011 Nov;80(2):e229-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.058. Epub 2011 Mar 10. PubMed PMID: 21398129.

[17] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Optimal monochromatic energy levels for virtual monochromatic imaging of gemstone spectral imaging in abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011 Sep-Oct;35(5):599-605. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318226a074. PubMed PMID: 21940992.

[18] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Virtual monochromatic imaging with dual-energy CT: optimization of keV settings for iodine contrast enhanced abdominal examination. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057135. Epub 2013 Feb 28. PubMed PMID: 23460796; PMCID: PMC3584035.

[19] Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977 Mar;33(1):159-74. PubMed PMID: 843571.

[20] Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005 May;37(5):360-3. PubMed PMID: 15883508.

[21] Barrett JF, Keat N. Artifacts in CT: recognition and avoidance. Radiographics. 2004 Sep-Oct;24(6):1679-91; quiz 1714-5. doi: 10.1148/rg.246045065. PubMed PMID: 15537978.

[22] Hsieh J. Computed tomography: principles, design, artifacts, and recent advances. Bellingham (WA): SPIE Press; 2009.

[23] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Radiation dose reduction in dual-energy CT using fast kVp switching. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Jul;197(1):W56-61. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5910. PubMed PMID: 21700943.

[24] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Noise reduction using adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction in abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010 May-Jun;34(3):430-4. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181d47dff. PubMed PMID: 20495409.

[25] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction: image quality and dose reduction for CT of the abdomen. Radiology. 2010 Aug;256(2):597-605. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091559. Epub 2010 Jun 3. PubMed PMID: 20519542.

[26] первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Virtual monochromatic imaging in dual-energy CT: concept and potential clinical applications. Radiographics. 2011 Nov-Dec;31(7):1673-97. doi: 10.1148/rg.317115028. PubMed PMID: 22084335.

[27] Cui YL, Chen L, Wang YN, первичный D, первичный D, первичный D, et al. Dual-energy CT virtual monochromatic imaging at 70 keV improves image quality for abdominal conventional CT. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147198. eCollection 2016. PubMed PMID: 26799415; PMCID: PMC4722058.