Abstract

Plant cells exhibit two distinct cell cycle types: the mitotic cycle, where DNA replication is tightly linked to mitosis, and the endocycle, characterized by DNA replication without subsequent cell division. To delve into the intricacies of DNA replication programs within these cycles, we conducted a study using maize (Zea mays) root tips. We employed pulse labeling with 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) in intact root tips, followed by flow sorting of nuclei, to meticulously examine DNA replication timing (RT) during the transition from a mitotic cycle to an endocycle. A detailed comparison of sequence-based RT profiles revealed a striking similarity: the majority of the maize genome replicates at comparable times during the S phase in both mitotic and endocycling cells. This consistency is observed despite the endocycle necessitating the replication of twice the amount of DNA and its typical association with cell differentiation. However, we identified regions encompassing approximately 2% of the genome that displayed significant alterations in replication timing between the two cell cycle types. Predominantly small, with a median size of 135 kb, these regions predominantly shifted to a later RT in the endocycle and showed an enrichment for genes expressed in the root tip. Notably, we also discovered larger regions with altered RT within the centromeres of seven out of the ten maize chromosomes. These regions encompassed the majority of the functionally defined centromere, which spans 1 to 2 Mb in size in the reference genome. In mitotic cells, these centromeric regions primarily replicate during mid S phase, but in endocycling cells, their replication shifts to late S phase. Conversely, the immediately adjacent pericentromere sequences consistently exhibited late replication in both cell cycles. Investigating CENH3 enrichment levels in 8C versus 2C nuclei suggested only a partial replacement of CENH3 nucleosomes after endocycle replication completion. This observed shift to later centromere replication, coupled with a potential reduction in CENH3 enrichment post-endocycle replication, aligns with the hypothesis that centromeres undergo inactivation when their function becomes dispensable.

Author Summary

Cell division, or mitosis, is a fundamental process where a cell’s genetic material duplicates and subsequently divides between two daughter cells. In contrast, certain specialized cell types undergo a process called the endocycle, where DNA is duplicated again without cell division, resulting in cells with twice the DNA content. This endocycle phenomenon is prevalent during plant development. In both mitotic and endocycles, DNA replication follows a precise program, unraveling and replicating compacted DNA in sections at different times during the synthesis (S) phase. In plants, it remains unclear whether these replication programs are identical in mitotic and endocycling cells, particularly as endocycling cells are typically undergoing differentiation. Using maize root tips, we performed a detailed Comparing Dna replication timing analysis between mitotic and endocycling cells. Our findings indicate that while the replication timing programs are largely similar, a small fraction of the genome exhibits a shift in replication timing during the endocycle, typically towards later S phase. Some of these regions are distributed across the genome and correlate with active genes. However, the most significant timing shifts occur in centromeres. This shift to later centromere replication is particularly noteworthy because centromeres are crucial for chromosome segregation during cell division, a function that is not required in the endocycle.

Introduction

Endoreduplication, also known as endocycling, is a developmentally programmed phenomenon where DNA replication occurs without nuclear breakdown, chromosome condensation, or cell division. This process is widespread in both plants and animals [1–3]. In plants, endoreduplication is a systemic feature [4], frequently playing a crucial role in the development of various tissues and organs, including fruit, endosperm, leaf epidermal cells, and trichomes [5]. The initiation of endocycling is often associated with a shift from cell proliferation to cell differentiation and expansion [6]. In plant roots, cells at the tip undergo active division through normal mitosis, while endocycling cells become more prevalent further from the tip, in a zone linked to differentiation and increased cell size [7, 8]. In maize (Zea mays) roots, the initial 1-mm segment primarily consists of actively dividing mitotic cells [8, 9]. Mitotic activity persists in the 1 to 3-mm region from the tip, but within this zone, approximately 30% of cells undergo a single endocycle. Instead of proceeding through mitosis and reverting to a 2C nuclear DNA content, these cells replicate their DNA without undergoing mitosis, transitioning directly from 4C to a final DNA content of 8C [8]. Beyond 3 mm, cell differentiation becomes dominant, and DNA replication activity diminishes significantly [8, 10]. Thus, while not all differentiating cells undergo endocycle, in those that do, the endocycle either precedes or accompanies cellular differentiation.

In animal systems, distinct cell types often exhibit variations in the temporal order of DNA replication along chromosomes, referred to as the “replication timing (RT) program.” These differences in RT programs are likely correlated with alterations in chromatin structure and gene expression during differentiation (e.g., [11–14]). However, information regarding potential changes in RT programs associated with endoreduplication or differentiation in plant systems remains scarce. Apart from a few model systems (e.g., [15, 16]), isolating individual cell types from plant organs is challenging, and DNA replication primarily occurs in meristematic regions, which are small and often inaccessible. Furthermore, plant cells do not maintain their differentiated state when cultured in suspension [17, 18]. Consequently, opportunities to comparing DNA replication timing programs in individual plant cell types are limited. However, the co-occurrence of endocycling and differentiating cells near the apical meristem of maize root tips, where we previously characterized the mitotic RT program [19], provides a unique setting to compare the two modes of replication within an intact plant organ.

We have developed a system for analyzing DNA replication in maize roots [8, 20], employing approaches similar to those used in our Arabidopsis cell suspension studies [21]. This system involves in vivo labeling of newly replicated DNA with the thymidine analog, 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU), and subsequent separation of labeled nuclei by flow cytometry into populations representing different stages of S phase. A key advantage of using EdU over 5-bromo-2’deoxyuridine (BrdU), traditionally used in replication timing by sequencing (Repli-seq) protocols [12], is the ability to sort nuclei based on both DNA content and EdU incorporation, followed by immunoprecipitation of EdU-labeled DNA. This modification allows for the precise separation of non-replicating, unlabeled G1 and G2 nuclei from labeled S-phase nuclei during flow sorting.

Cytological analysis of sorted, EdU-labeled nuclei revealed that replication activities in early and mid S phases are more interspersed within the maize nucleus compared to animal cells [22, 23]. We previously characterized the RT program in mitotic cells of the apical 1-mm root segment [19], using a modified Repli-seq protocol [24]. In mitotic cells, we found evidence of a gradient of early replicating, open chromatin transitioning gradually into less open and less transcriptionally active chromatin replicating in mid S phase. We also corroborated cytological observations showing that heavily compacted classical heterochromatin, including knobs and pericentromeres, primarily replicate in late S phase [22, 25]. While these relationships between RT and chromatin packaging are generally consistent with findings in other systems, we did not detect megabase-scale replication domains, as characterized in mammalian cells (reviewed in [26] and references therein).

Although replication in the first 1-mm of the root is predominantly mitotic, with DNA contents of labeled nuclei ranging from 2C to 4C, flow cytometry profiles of nuclei from root tissue between 1 and 3-mm from the tip also included a significant population of nuclei with DNA contents exceeding 4C. The emergence of endopolyploid (8C) nuclei in this zone is expected, as some 4C nuclei are known to enter the endocycle rather than undergo division [7, 8]. Cytological analysis of replicative labeling indicated that the spatiotemporal patterns of replication during the 4C to 8C transition in these endocycling nuclei closely resemble those in mitotic nuclei [22]. However, it remained to be determined whether the entire genome is uniformly replicated during the endocycle and whether the temporal program is altered in differentiating cells when replication occurs without intervening mitosis.

Both under-replication and over-replication (amplification) have been observed in various animal systems during developmentally programmed endocycles, particularly in Drosophila (reviewed in [27]). Besides the well-known amplification of chorion genes and under-replication of heterochromatin, under-replication also occurs in several euchromatic regions, exhibiting tissue specificity that suggests a potential role in differentiation [28–30].

Despite the prevalence of endopolyploidy in plants, reports on over- or under-replication of specific sequences are limited. Some orchids exhibit a phenomenon where only a fraction of the genome is endoreplicated [31, 32], but in most cases, endopolyploid cells have DNA contents that are multiples of the 2C value. Both highly repetitive heterochromatic regions and highly expressed genes are extensively endoreduplicated in maize endosperm nuclei, consistent with uniform replication of the entire genome [33]. More conclusively, whole-genome sequencing in Arabidopsis demonstrated that leaf nuclear DNA is evenly endoreduplicated in wild-type plants, although the same experiments clearly showed selective over-replication in atxr5 and atxr6 mutants [34].

To address the questions of over- or under-replication and developmentally associated changes in RT programs in the maize root tip system, we performed a detailed comparing DNA replication dynamics in mitotic and endocycling cells. Our findings revealed minimal evidence for over- or under-replication in endocycling cells, aligning with previous plant system reports. We also observed that RT programs are largely conserved across the genome. However, we identified significant timing alterations for specific loci, accounting for 2% of the genome. Most notably, we found major changes in centromere RT, shifting from mid S phase in mitotic cells to primarily late S phase in the endocycle.

Results

Separating Endocycling from Mitotic Nuclei

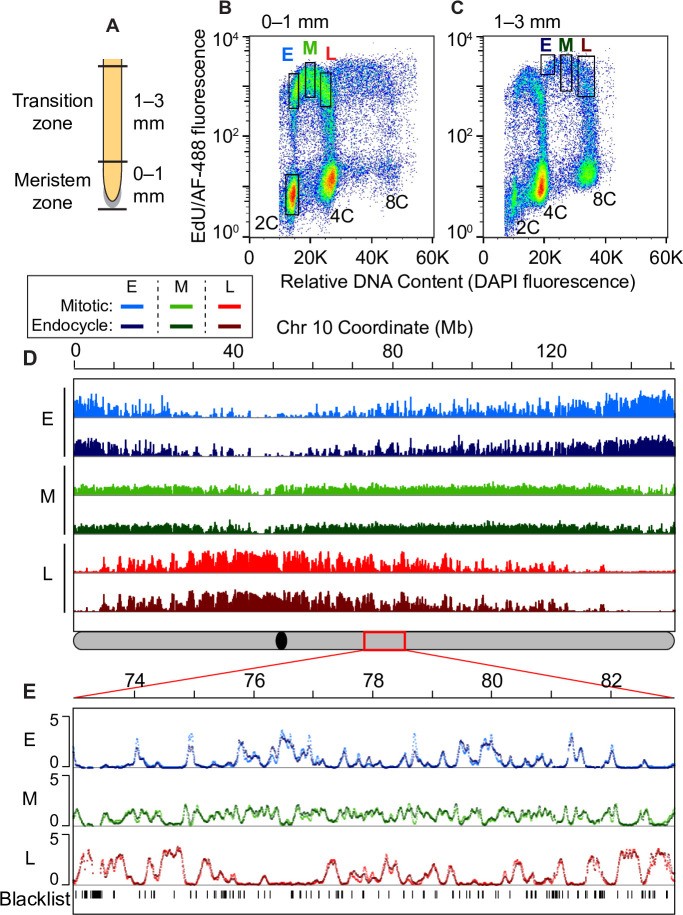

As previously reported and detailed in Methods, we used a 20-minute pulse of the thymidine analog, EdU, to label newly replicated DNA in intact maize roots. This was followed by formaldehyde fixation and isolation of nuclei from defined root tip segments (Fig 1A). Incorporated EdU was conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (AF-488) using “click” chemistry [35]. The nuclei were then stained with DAPI and fractionated by two-color fluorescence-activated flow sorting to generate populations at different stages of the mitotic cell cycle or the endocycle [8, 20]. Fig 1B and 1C illustrate flow cytometry profiles for root segments 0–1 mm and 1–3 mm from the tip, respectively. Fluorescent signals from nuclei that incorporated EdU during S phase of a normal mitosis form an “arc” between 2C and 4C DNA contents (Fig 1B). Previous EdU pulse-chase time course experiments in the 0–1 mm region showed that most labeled 4C nuclei return to 2C, as expected in a mitotic cycle (see Fig 1B in [36]). In the 1–3 mm zone, a substantial fraction of labeled nuclei is undergoing endoreplication, forming a similar arc with DNA contents ranging between 4C and 8C (Fig 1C). As shown in Fig 1C, the endocycle arc is more prominent in nuclei preparations from 1–3 mm root segments. To analyze the endocycle RT program, detailed below, labeled nuclei representing early, mid, and late S-phase fractions were separated using the sorting gates in Fig 1C, adjusting the endocycle early gate to avoid contamination from mitotic nuclei in late S phase. Reanalysis of sorted nuclei confirmed effective separation between nuclei populations from the adjusted early sorting gate and the mid sorting gate (S1 Fig). To complete the Repli-seq protocol, detailed below, DNA was extracted from nuclei in each gate and sheared. Labeled, newly replicated DNA from each S-phase fraction was then immunoprecipitated and sequenced.

Fig 1. Global comparison of mitotic cycle and endocycle replication timing programs.

Image alt text: Flow cytometry analysis comparing DNA replication in maize root tip meristem and transition zones. (A) Diagram of maize root zones used for Repli-seq. (B) Flow cytogram of 0-1mm root segment nuclei (mitotic cycle). (C) Flow cytogram of 1-3mm root segment nuclei (endocycle). (D) Replication timing (RT) profiles for chromosome 10 in mitotic vs. endocycling cells. (E) Expanded view of a 10 Mb region on chromosome 10 showing similar mitotic and endocycle RT profiles.

(A) Schematic of a maize root showing the meristem zone (0–1 mm region) and transition zone (1–3 mm region) used for Repli-seq experiments. (B and C) Flow cytograms of nuclei isolated from the 0–1 mm root segments (B) and 1–3 mm root segments (C). Dots are pseudo-colored by density and black rectangles represent the sorting gates used to collect the pre-replicative 2C reference sample and early (E), mid (M) and late (L) S-phase fractions from either the mitotic cycle or endocycle. (D) Global scale view of replication timing (RT) for chromosome 10, comparing DNA replication timing profiles between mitotic and endocycling cells in early, mid and late S phase. Uniquely mapping reads were aggregated in 3-kb windows, normalized for sequencing depth, divided by the normalized 2C reference read counts, and Haar wavelet smoothed (see Methods). The global RT profiles for mitotic and endocycling cells are very similar to each other for all ten chromosomes. The schematic of chromosome 10 at the bottom shows the location of the centromere (black oval) and the 10 Mb region that is expanded in panel E (red rectangle). (E) Expanded view of a 10 Mb region on chromosome 10 with overlaid mitotic and endocycle RT profiles. Unmappable or multi-mapping regions (“blacklist”) were identified from the pre-replicative 2C reference sample and are indicated as tick marks in the bottom track. This example illustrates the similarity between the mitotic and endocycle RT profiles that is observed throughout most of the genome. Scale for all panels: 0–5 normalized replication signal.

The versatility of the EdU labeling and flow sorting system also allowed us to collect unlabeled nuclei, representing non-S-phase cells with 2C, 4C, and 8C DNA contents. These nuclei were used to characterize selected histone marks following mitotic or endocycle replication and to investigate the copy number of individual loci across the genome.

Evidence for Complete Genome Replication During the Endocycle

Given the well-documented instances of over- and under-replication during the endocycle in animal systems, we investigated whether local copy number differences exist in the maize genome after endocycle replication. To achieve this, we utilized the non-S-phase 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei populations described above and performed whole-genome paired-end sequencing. To enhance the representation of repeat region copy numbers, we included reads that could not be uniquely mapped, retaining only the primary alignment location for each read pair. This approach was exclusively used for copy number analysis, while all subsequent analyses included only uniquely mapping reads (see Methods and S1 Text). For each ploidy level, we examined data for regions where normalized read frequencies in 5-kb windows differed between 8C and 4C or 4C and 2C nuclei, using procedures described by Yarosh et al. ([37]; S1 Text). We found approximately 5% of the 5-kb windows had ratio values falling outside two standard deviations of the mean ratio for 4C and 2C or 8C and 4C (1.0 ± 0.2 S. D. for both; S2A and S2B Fig). However, these windows were either singleton 5-kb windows scattered across the genome (S2C Fig) or coincided with regions with very low read mapping in the 2C sample, suggesting they are likely spurious results of ratios between windows with very few reads in both samples. Thus, there is minimal evidence of significant over- or under-replication of genomic regions in nuclei with different ploidy levels.

To further assess complete replication of high-copy repeats not well represented in the genome assembly, we used BLAST software to query all reads, not just genome-mapped reads, to determine the percentage of reads corresponding to consensus sequences for high-copy repeats (S1 Text). Analyzed sequences included knob repeats knob180 and TR-1 [38, 39], 5S and 45S rDNA repeats [40], and centromere-associated CentC satellite repeats [41]. We also queried consensus sequences for centromere retrotransposons of maize (CRM) families 1–4 [42–45]. In all instances, percentages were similar across 2C, 4C, and 8C samples (S2D and S2E Fig), further indicating minimal or no over- or under-replication.

Replication Timing Analysis

As described earlier, we sorted endocycling nuclei from S-phase populations in Fig 1C, then extracted and sheared DNA from each fraction. EdU-containing DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated (IP) using an antibody to AF-488, resulting in sequence populations representing DNA replicating during early, middle, or late S phase of the endocycle. Given that EdU/AF-488-labeled DNA is immunoprecipitated from a population of only EdU-labeled nuclei (see Fig 1B and 1C), the unlabeled DNA background in each IP is significantly lower than if nuclei were sorted solely by DNA content. We also prepared DNA from the unlabeled 2C nuclei pool as a pre-replicative reference dataset. DNA from three biological replicates of each sample was sequenced to generate paired-end reads.

To comparing DNA replication timing programs in endocycling and mitotic nuclei, we mapped our previous Repli-seq data for mitotic nuclei [19] and our new endocycle data to the maize B73 RefGen_v4 genome, which includes improved centromere assemblies and more complete transposable element (TE) annotations [46, 47]. Including only uniquely mapped reads resulted in read depths between 65.7 million and 261.2 million reads per S-phase fraction (including reads from 3 biological replicates per S-phase fraction). Data from all S-phase samples for mitotic and endocycle were randomly downsampled to the lowest read depth (65.7 million reads) to ensure comparable results (see Methods and S1 Spreadsheet).

We utilized the Repliscan analysis pipeline [24] to generate continuous normalized data profiles representing replication activity intensity across the genome (RT profiles) in early, mid, and late S-phase fractions. These RT profiles were generated by aggregating Repli-seq read densities for each S-phase sample in 3-kb static windows, scaling reads to 1× genome coverage, dividing by scaled read counts from unlabeled 2C reference data, and smoothing using Haar wavelet transform (see Methods and [24]). Normalization with the pre-replicative 2C reference provided a uniform 2C copy number and corrected for sequence mappability differences and collapsed repeats that caused data “spikes” (illustrated for late endocycle replication in S3 Fig), while preserving replication signal [24, 48]. 3-kb windows with no or extremely low read coverage in the 2C reference sample (see Methods) were excluded from analyses. These windows include unmappable and multi-mapping regions (“blacklist” windows, indicated by black tick marks in Fig 1E). After RT profile normalization, the result is an estimate of replication activity intensity in each 3-kb window, termed “replication signal.”

Fig 1D demonstrates that global RT profiles are remarkably similar in endocycling and mitotic nuclei, with overlays showing primarily minor differences (Fig 1E). Pearson’s correlation coefficient values between corresponding S-phase fractions from mitotic and endocycle data are very high (r values of 0.91, 0.89, and 0.96 for early, mid, and late, respectively). These values are comparable to those found between individual biological replicates within each sample (S4 Fig).

Identifying Regions of Altered Timing

Despite the overall similarity of mitotic and endocycling cell RT programs, regions scattered across the maize genome exhibit replication timing shifts. To identify regions with differential replication timing (DRT), we first calculated the difference in normalized replication signal between mitotic and endocycle data at each genomic location for early, mid, and late profiles separately (S1 Table; S5 Fig). We then focused our analysis on regions with an equal and opposite DRT in at least one other S-phase fraction (e.g., regions where decreased early replication signal in endocycling cells was associated with a corresponding increase in mid and/or late replication signal at the same location). We allowed a 6-kb gap distance when searching for DRT regions to account for small blacklist regions interrupting larger change regions. We found 11% of the genome showed a replication signal difference of at least 10% of the total difference range for a given S-phase fraction (absolute difference in replication signal ≥ 0.4; S1 Table), with an opposite replication signal difference at the same threshold criterion at the same location in another S-phase fraction. Many regions are small, with the lower 50% ranging from 3 kb to a median size of 33 kb (S2 Table). Given that replication initiation, elongation, and termination units (“replicons”) in monocot plants are estimated to average 47 ± 13 kb [49], the biological relevance of RT differences in much smaller regions is unclear. However, instead of imposing an arbitrary size cutoff, we focused on regions associated with at least one core region with a larger (≥ 25%) DRT, as described below.

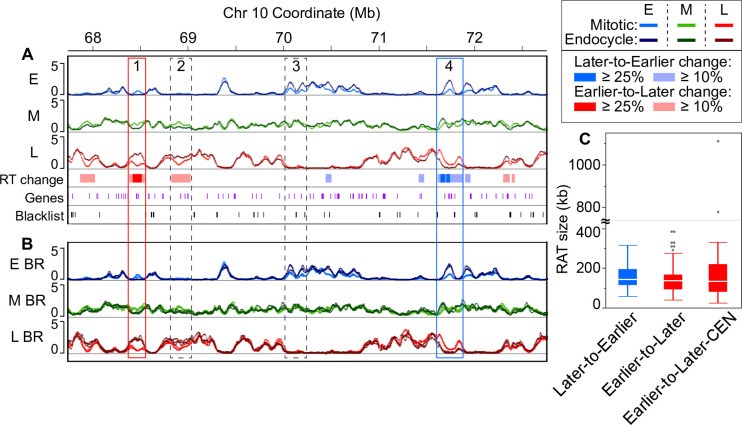

To identify more robust RT differences, designated Regions of Altered Timing (RATs), we identified regions with DRT ≥ 25% of the total difference range for a given S-phase fraction (absolute difference in replication signal ≥ 1.0; S1 Table), also meeting the criterion of opposite DRT in at least one other S-phase fraction. To highlight larger contiguous change regions, we included ≥ 10% regions adjacent to original ≥ 25% regions. However, RATs needed at least one core region with DRT ≥ 25% (S2 Table) for inclusion. Representative ≥ 25% and ≥ 10% regions are shown by various shades of red and blue bars in Fig 2 (additional examples in S6 Fig). Finally, we examined RT profiles for RATs in individual biological replicates to verify replicate agreement (Figs 2B and S6). Selecting only robust RATs excluded regions with less dramatic RT changes—e.g., dashed boxes in Fig 2. In such regions, DRT did not meet our ≥ 25% replication signal difference criterion (box 2 in Fig 2A) and/or lacked equal and opposite (“compensated”) DRT (box 3 in Fig 2A).

Fig 2. Identifying regions of altered timing.

Image alt text: Replication Timing (RT) profiles and Regions of Altered Timing (RATs) in maize chromosome 10. (A) RT profiles showing Earlier-to-Later (red box 1) and Later-to-Earlier (blue box 4) RATs. Dashed boxes indicate non-robust DRT regions. (B) RT profiles with biological replicates overlaid for RAT validation. (C) Boxplots of RAT size distributions for Later-to-Earlier, Earlier-to-Later, and centromere (CEN) RAT categories.

(A) An example region (5 Mb) on chromosome 10 containing two robust Regions of Altered Timing (RATs), indicated by boxes outlined with solid lines. The RAT in box 1 (red) shifts from Earlier-to-Later, and the RAT in box 4 (blue) shifts from Later-to-Earlier. Dashed boxes denote regions with some level of difference in RT (DRT) in which the magnitude of the difference did not meet our ≥ 25% criterion (box 2), or in which the change in one S-phase fraction was not compensated by an opposite change in at least one other S-phase fraction (box 3). Annotated genes (purple) and unmappable or multi-mapping regions (“blacklist”, black) are indicated as tick marks in the bottom tracks. (B) The same chromosome region as in (A) with the individual biological replicate RT profiles overlaid to demonstrate that RATs are not caused by local regions of technical variation between replicates. Scale for panels A and B: 0–5 normalized replication signal. (C) Boxplots representing the distribution of RAT sizes in the three categories: Later-to-Earlier, Earlier-to-Later, and a subset of Earlier-to-Later RATs found in functional centromeres (CEN) [46]. Boxplot whiskers represent 1.5 x interquartile range (IQR). The axis is broken to show two values that are much higher than the others and correspond to large RATs in CEN 9 and CEN 10. However, it is important to note that the sizes of CEN RATs are underestimated, because centromeres contain variable numbers and sizes of blacklist regions, which break up what would probably be long continuous RATs (see Fig 4 and Table 2).

Robust RATs fall into two categories: those with strongest replication signal later in the mitotic cycle than in the endocycle (“Later-to-Earlier” shift), and those with strongest signal earlier in the mitotic cycle than in the endocycle (“Earlier-to-Later” shift). Additionally, we separately characterized a subset of Earlier-to-Later RATs located in functional centromeres (“Earlier-to-Later-CEN”) using centromere (CEN) coordinates from [46]. Our stringent criteria identified RATs comprising only about 2% of the maize genome (Table 1), with 233 of 274 total regions (1.6% of genome) in the Earlier-to-Later category. Non-CEN Later-to-Earlier and Earlier-to-Later RATs have similar size distributions, with median sizes of 141 and 135 kb, respectively (Fig 2C and Table 1). All CEN RATs are Earlier-to-Later, with a median size of 132 kb, similar to non-CEN RATs. However, CEN RAT sizes are underestimated due to numerous blacklist regions within centromeres breaking likely continuous RATs into smaller parts in our analysis. Even though maize centromeres are well sequenced [46], they still contain gaps and regions with non-uniquely mappable reads in the current B73 RefGen_v4 genome assembly. To address this, we calculated an upper estimate of continuous RAT size by incorporating coverage from multiple RATs within each centromere, RATs extending past CEN boundaries (“presumed CEN RATs”), and interspersed blacklist regions. This upper estimate of CEN RAT size, detailed below, ranges from approximately 0.9–2 Mb per CEN (Table 2).

Table 1. RAT summary table.

| RAT category | Count | Median size (kb) | Coverage (kb) | % of genome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-centromere | ||||

| Later-to-Earlier | 41 | 141 | 6,291 | 0.30 |

| Earlier-to-Later | 192 | 135 | 26,907 | 1.28 |

| Centromere | ||||

| Earlier-to-Later-CEN | 41 | 132 | 7,668 | 0.36 |

| Earlier-to-Later total | 233 | 135 | 34,575 | 1.64 |

| RAT total | 274 | 135 | 40,866 | 1.94 |

Table alt text: Summary table of Regions of Altered Timing (RATs) in maize genome. Table shows count, median size, coverage, and genome percentage for Non-centromere (Later-to-Earlier, Earlier-to-Later), Centromere (Earlier-to-Later-CEN), Earlier-to-Later total, and RAT total categories.

A summary of the region count, median size, total genome coverage, and percentage of the entire genome represented in each RAT category.

Table 2. Centromere RAT coverage and size estimates.

| CEN | CEN size total (kb)a | CEN excluding blacklist (kb)b | ≥10% DRT coverage (kb)c | Final RATs coverage (kb)d | Presumed CEN RAT coverage (kb)e | RAT countf | Continuous RAT size (kb)g | % CEN covered by continuous RATh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 350 | 329 | 15 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 1980 | 1275 | 1139 | 986 | 220 | 7 | 2037 | 86.9 |

| 3 | 1150 | 667 | 498 | 453 | – | 6 | 897 | 78.0 |

| 4 | 1430 | 968 | 706 | 538 | 14 | 7 | 945 | 65.1 |

| 5 | 2280 | 1806 | 1440 | 1407 | – | 7 | 1782 | 78.2 |

| 6 | 800 | 764 | 390 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7 | 300 | 285 | 45 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8 | 1540 | 1210 | 1190 | 1046 | 10 | 7 | 1419 | 91.5 |

| 9a | 1650 | 1602 | 1510 | 1510 | 71 | 4 | 1641 | 95.7 |

| 9b | 400 | 334 | 18 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 1390 | 1306 | 1269 | 1221 | 192 | 3 | 1506 | 94.5 |

Table alt text: Centromere RAT coverage and size estimates for maize chromosomes. Table details CEN size, blacklist exclusion, DRT coverage, RAT coverage, presumed CEN RAT coverage, RAT count, continuous RAT size, and percentage of CEN covered by continuous RAT for each centromere.

a Centromere size reported in [46], which includes unmappable regions of known size.

b Centromere size, excluding blacklist regions (unmappable and multi-mapping) that are >6 kb in size. A gap distance of 6 kb was allowed during RAT analysis.

c The combined coverage of regions with ≥10% DRT called within each centromere, not including blacklist regions >6 kb.

d The combined coverage of final RATs called within each centromere, not including blacklist regions >6 kb. Final RATs contained at least one core region with ≥25% DRT (see Methods).

e In some centromeres, the called RAT extends past the previously reported CEN boundary. These areas are labeled ‘presumed CEN RAT’.

f The number of individual RATs called in each centromere.

g Continuous RAT size is defined by summing the coverage of CEN RATs, presumed CEN RATs, and the interspersed blacklist regions to generate an upper estimate of full RAT size. This estimate still cannot take into account gaps in the centromere assemblies that are of unknown size.

h The percentage of the CEN size total that is covered by the estimated continuous RAT, without taking into account presumed CEN RATs outside CEN boundary.

A summary of the various estimates of coverage in individual centromeres of regions with DRT, and continuous RAT size.

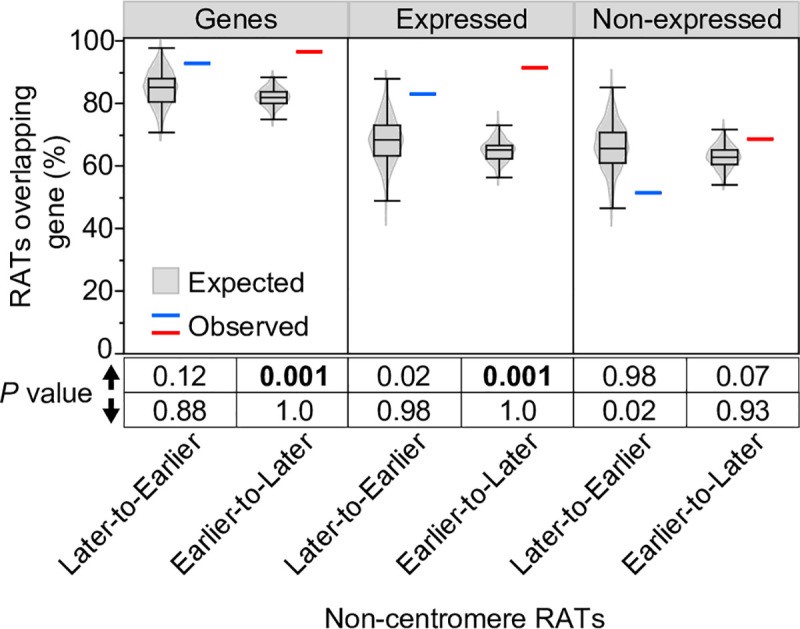

Non-centromeric RATs

We analyzed non-CEN RATs for gene and TE content, histone modifications, and functional annotations of genes within RATs. To assess if the percentage of gene-containing RATs differed from random expectation, we randomly shuffled coordinates of non-CEN Later-to-Earlier and Earlier-to-Later RATs across the genome 1000 times and calculated the percentage of randomly shuffled regions overlapping genes in each set. These “expected” random distributions were compared to observed percent overlap values for Later-to-Earlier and Earlier-to-Later RATs, and a permutation P value was calculated (see Methods). We found that 93% and 96% of Later-to-Earlier and Earlier-to-Later RATs, respectively, contain at least one annotated gene, typically a small cluster of 2–3 genes (Fig 3 and S3 Table). The observed 96% overlap of Earlier-to-Later RATs with genes is significantly greater than expected by chance (permutation P value = 0.001; Fig 3). To assess gene expression, we used root-tip RNA-seq data (not specific to mitotic or endocycle cells) and found that while only 50% of the 682 genes in non-CEN RATs are expressed at a meaningful level (FPKM ≥ 1), 83% and 91% of Later-to-Earlier and Earlier-to-Later RATs, respectively, still contain at least one expressed gene (S3 Table). The 91% overlap of Earlier-to-Later RATs with expressed genes is also significantly greater than expected by chance (permutation P value = 0.001; Fig 3). In contrast, only 51% and 68% of Later-to-Earlier and Earlier-to-Later RATs, respectively, contain genes not expressed in the root (Fig 3). These non-expressed gene values are not significantly different from random expectation, indicating that gene enrichment in Earlier-to-Later RATs is mainly driven by expressed genes.

Fig 3. Permutation analysis of the percentage overlap of non-CEN RATs and genes.

Image alt text: Statistical analysis of gene overlap with Regions of Altered Timing (RATs). Violin plots and boxplots showing observed and expected percentage overlap of non-centromeric RATs with all genes, expressed genes, and non-expressed genes based on permutation testing.

The percentage of RATs that overlap genes, expressed genes or non-expressed genes was calculated for non-CEN RATS and corresponding 1000 randomly shuffled sets (see Methods). The observed percentage for Later-to-Earlier (blue line) and Earlier-to-Later (red line) RATs are plotted alongside the expected percentage distribution of the 1000 random sets (grey violin plots overlaid with boxplots). Permutation P values below the graph were calculated from the proportion of the 1000 random sets that had a percent overlap value greater than (up arrow) or less than (down arrow) the observed value. Permutation P values ≤ 0.001 are considered evidence that the observed percent overlap is significantly different than random expectation.

The significant enrichment of root-expressed genes in Earlier-to-Later non-CEN RATs suggests these regions may be related to gene expression shifts. However, direct comparison of gene expression in RATs in mitotic and endocycling cells was limited by insufficient RNA quality for sequencing from fixed, sorted nuclei. Instead, we assessed gene-associated histone post-translational modifications in sorted non-S-phase 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei. Our previous work in maize root mitotic cells showed that trimethylation of H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and acetylation of H3 lysine 56 (H3K56ac) modifications tend to colocalize on active genes and are associated with earlier replicating regions, while trimethylation of H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) tends to be on repressed genes regardless of RT [19]. For each ploidy level, we quantified the percentage of genes within RATs with each mark and the fold enrichment relative to input for called peaks within genes. Few differences exist between ploidy levels in the number of genes bearing these marks (S7D Fig), but minor shifts occur in peak enrichment in 8C nuclei compared to 2C (S7A–S7C Fig). The clearest shift is a decrease in H3K4me3 enrichment on expressed genes in Earlier-to-Later RATs (S7B Fig), suggesting these genes may have reduced expression in endocycling cells.

We also performed gene ontology (GO) analysis for genes in non-CEN RATs to identify enriched functional annotations in genes with RT shifts, focusing on root tip-expressed genes (S2 Spreadsheet). We found 44 significantly enriched GO terms for genes within Earlier-to-Later RATs, including biological process and molecular function terms related to gene expression, DNA/RNA metabolism, and the cell cycle (S8 Fig). A wide variety of significant cellular component GO terms were also found, potentially related to differentiation processes in endocycling cells. No significant GO terms were found for genes within Later-to-Earlier RATs, likely due to the limited number of expressed genes (52) in this RAT category. Taken together, transcription-related histone modification analyses and functional annotations suggest a role for gene expression changes in Earlier-to-Later RATs. Given the later RT shift in endocycle for these regions, decreased gene expression would be expected [19]. However, further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The maize genome is generally organized with genes clustered in “islands” interspersed with transposable element blocks [50–52]. We used a permutation strategy to estimate the significance of differences in percent coverage of TEs and individual TE superfamilies in non-CEN RATs, comparing DNA sequence composition. Observed coverage values were compared to random expectation from 1000 shuffled sets. TE annotations were from the recent B73 RefGen_v4 TEv2 disjoined annotation, where every bp is assigned to a single TE [47]. We found no TE superfamilies with percent coverage values in non-CEN RATs significantly different from random expectation at a permutation P value threshold of 0.001, although one TE superfamily, RLG/Gypsy, was close to the threshold for significant depletion in Earlier-to-Later RATs (permutation P value = 0.002; S9 Fig). RLG/Gypsy elements constitute 32% of Earlier-to-Later RAT coverage and 32–40% of randomly shuffled set coverage. We also found similar percent AT content in RATs and the whole genome, with median values of 55% and 56% for Later-to-Earlier and Earlier-to-Later RATs, respectively, compared to a 55% median for the whole genome (S10 Fig). Overall, there is no evidence of AT content difference or major enrichment/depletion in specific TE superfamily coverage in non-CEN RATs, with a possible minor RLG/Gypsy element coverage depletion in Earlier-to-Later RATs. Given RLG/Gypsy elements’ most abundant coverage across the B73 reference genome [46], this minor depletion may be related to increased gene presence in Earlier-to-Later RATs (Fig 3).

Centromeric RATs

Functional centromeres are defined by nucleosomes containing the centromere-specific histone variant CENH3 in plants and CENP-A in animals. CENH3/CENP-A constitutes a small percentage of total centromeric H3, but is crucial for kinetochore protein recruitment [53–55]. Maize centromeres are unusually well-mapped, allowing unique mapping of most centromeric reads [56]. In our Repli-seq data, on average 45% of all centromere-mapping reads were uniquely mapped (S11 Fig). Only these uniquely mapping reads were used for further analysis. Additionally, most maize centromere assemblies are relatively intact, and functional centromeres have been located by mapping ChIP-seq reads for CENH3 [46]. Combined with our replication timing data, these maize system features offer a unique opportunity to assess centromere RT programs.

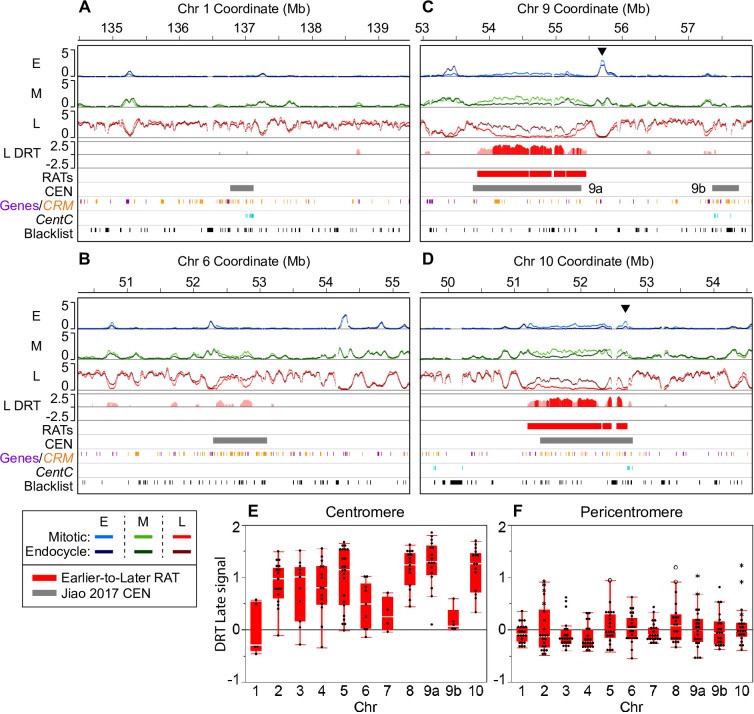

Our analysis identified large, robust RATs across seven of ten centromeres (Figs 4C, 4D and S12). These seven centromeres (CEN 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 10) were previously classified as “complex” due to a mixture of retrotransposons with some centromere satellite repeat arrays (CentC; [56, 57]). In the RefGen_v4 genome assembly, CEN 9 has two called CENH3-binding regions [46], referred to as CEN 9a and 9b (Fig 4C; grey bars). Interestingly, we only found robust RATs in the larger CEN 9a, with minor RT shift in smaller CEN 9b (Fig 4C and Table 2). Cumulative RAT coverage in each complex CEN ranges from 0.45–1.5 Mb (Table 2). However, due to blacklist regions varying in size and number within each centromere, automated analysis underestimated true RAT sizes. Therefore, we calculated an upper estimate of continuous RAT size in each centromere, including multiple RATs, interspersed blacklist regions, and coverage from CEN RATs extending past previously determined CEN boundaries (“presumed CEN RATs”). This upper estimate ranges from approximately 0.9–2 Mb per centromere, covering 65–95% of the previously defined functional centromere for the seven complex CENs (Table 2).

Fig 4. Large RATs correspond to functional centromeres.

Image alt text: Replication Timing (RT) profiles of maize centromeres showing large Regions of Altered Timing (RATs) in complex centromeres. (A-B) RT profiles for simple centromeres CEN1 and CEN6 with minor DRT. (C-D) RT profiles for complex centromeres CEN9 and CEN10 with large RATs. (E-F) Differential Replication Timing (DRT) plots for late RT profiles in centromeres and pericentromeres.

Our analysis found large RATs, sometimes broken by blacklist regions (black tick marks at the bottom of each panel) at each of the seven “complex” maize centromeres. The remaining three “simple” centromeres (on chromosomes 1, 6, and 7) showed various levels of DRT that did not meet the criteria for calling RATs in our initial analysis. (A–D) Each 5-Mb region shown contains early (E), mid (M) and late (L) RT profiles with mitotic and endocycle data overlaid (scale: 0–5 normalized replication signal). The difference in late replication signal (endocycle minus mitotic; labeled “L DRT”) for windows where the difference was compensated by an equal and opposite difference in the early and/or mid profiles is also shown. Late replication signal differences compensated at the ≥ 10% threshold (light red), and those compensated at the ≥ 25% threshold (dark red) are shown, but only regions that contained at least one ≥ 25% shift were classified as robust RATs in our initial analysis. Two examples of simple centromeres, CEN 1 (A) and CEN 6 (B), and two examples of complex centromeres, CEN 9 (C) and CEN 10 (D) are presented. The black arrowheads in panels C and D denote example regions with a peak of early replication signal within or adjacent to the centromere that also shows an increase in mid replication signal in the endocycle (for other examples, see S12 Fig). Colored boxes below the RT profiles denote Earlier-to-Later RATs (red) and the functional centromere (grey; [46]). Chromosome 9 contains two called CEN regions labeled 9a and 9b. The colored tick marks correspond to elements of centromeric retrotransposons of maize (CRM) families 1–4 (orange; [47]), gene annotations (purple; [46]), and mappable CentC satellite repeats (teal; [57]). Blacklist regions are indicated by black tick marks in the lowest track. (E and F) DRT (endocycle—mitotic) between late RT profiles for each centromere (E) and corresponding pericentromere (F; ± 1 Mb) were calculated in 100-kb static windows. In panel F, asterisks indicate DRT values from windows where an Earlier-to-Later-CEN RAT extends past the called CEN boundary [46] into the pericentromere (also see Table 2); open circles indicate windows that contain a non-CEN Earlier-to-Later RAT that met our compensation criteria. DRT values between early and mid profiles are shown in S13 Fig.

Upon inspecting RT profiles for each complex CEN, we found strongest replication signals mainly in mid S in mitotic cells, shifting to primarily late S in endocycling cells. Notably, while replication occurs mainly in mid S in mitotic cells, distinct early replication peaks exist inside or directly adjacent to the called centromere (black arrowheads in Figs 4 and S12) in all but one (CEN 5) complex centromere. These early peaks remain in the endocycle, though usually with reduced early signal and a concomitant mid signal increase at the same location.

The remaining three centromeres (CEN 1, 6, and 7) were previously characterized as “simple” due to mainly containing large CentC repeat arrays [56, 57]. In our analysis, simple centromeres showed at most small RT shifts not meeting robust RAT criteria (Table 2, Figs 4A, 4B and S12). However, CentC repeats are poorly represented in the reference genome assembly, making complete simple centromere RT profile analysis impossible. Assembly portions of CEN 7 replicate mainly in mid S phase in both mitotic and endocycling cells (S12 Fig), while CEN 1 and CEN 6 assembly sequences are mostly late replicating in both cell types, with minor RT changes across small regions (Fig 4A and 4B and Table 2).

Due to computational challenges in identifying continuous RATs, we focused subsequent analyses on the entire CENH3-binding region of each chromosome (excluding blacklist regions). We calculated the difference in early, mid, and late replication signal (endocycle minus mitotic) by averaging across 100-kb static windows. For comparison, we also calculated replication signal differences in pericentromeres, arbitrarily defined as ± 1 Mb flanking the CENH3 region. We inspected all RT differences in centromeres and pericentromeres without requiring DRT compensation in other S-phase fractions. Early and mid replication signals across complex centromeres decrease, and late replication signals increase in endocycling cells, reflecting a large shift toward late replication. DRT values for the late profile in centromeres and pericentromeres are shown in Fig 4E and 4F, respectively, while early and mid profile DRT values are in S13 Fig. Interestingly, DRT tapers off towards functional centromere edges (see profiles in Figs 4C, 4D and S12), and striking congruity exists in replication signals for mitotic and endocycling cells in immediately adjacent pericentromere regions (Fig 4A–4D). Pericentromeric RT shifts are smaller and less dramatic than those in centromeres proper (Fig 4F). Moreover, few (8%) pericentromeric windows with DRT are compensated by equal and opposite shifts in other S-phase profiles (S4 Table), suggesting many uncompensated differences may be technical variation rather than meaningful biological differences. In contrast, nearly all (85%) centromeric windows have compensated RT shifts.

Genomic Elements and Features in Centromeres

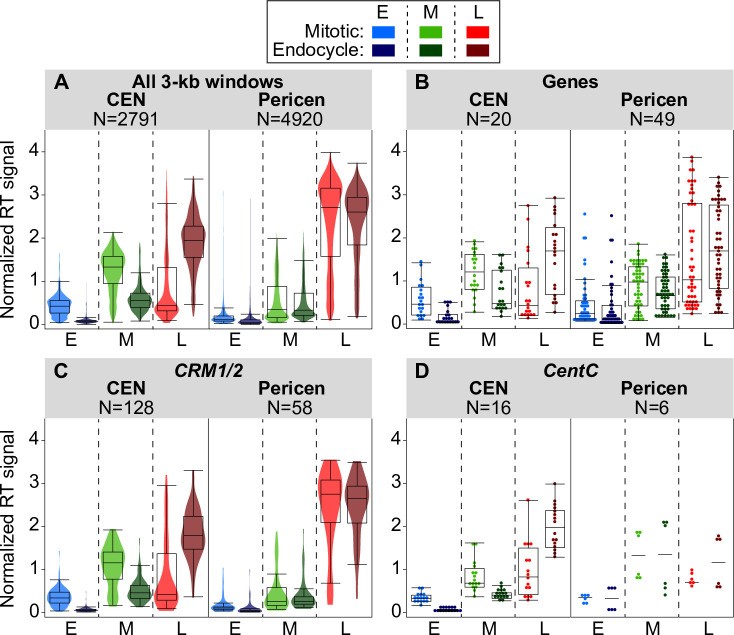

Maize centromeres contain varying amounts of tandemly arrayed CentC repeats (156-bp single repeats; [41]) and several CRM retrotransposon families interspersed with a few other retrotransposon families [44, 52, 58, 59]. CentC repeats and CRM elements are also present in adjacent pericentromeres without CENH3 binding [52, 58]. RefGen_v4 also annotates fifty genes within centromeres. We asked if all these centromeric sequence elements behave similarly in the mitotic-to-endocycle transition or if certain elements show larger RT shifts. We also asked if all three element types show similar RT changes in centromeres versus pericentromeres. Given 3-kb window replication signal values, we included elements covering at least half a window (1.5 kb) in our analysis. Fig 5 summarizes complex centromere data, while simple centromere data is in S14 Fig. Similar results were found when all elements were included (S14 Fig).

Fig 5. Comparing replication times for genomic features in complex centromeres and corresponding pericentromeres.

Image alt text: Replication Timing (RT) boxplots for genomic features in maize centromeres and pericentromeres. Boxplots compare RT signals during mitotic and endocycle S phases for 3-kb windows, genes, CRM1/2 elements, and CentC repeats within complex centromeres and pericentromeres.

(A–D) Boxplots comparing DNA replication signals during mitotic and endocycle S phases for centromeres, pericentromeres (± 1 Mb), and genomic features within them. The panels show the distributions of replication signals in early (E), mid (M), and late (L) S for all 3-kb windows (A), annotated genes (B), CRM1/2 elements (C), and mapped CentC repeats (D) in centromeres and pericentromeres. For panels A and C, colored violin plots are overlaid, while for panels B and D, individual data points are shown because of the smaller number of data points. The number of windows or elements included in each analysis is indicated above each graph. Only elements that covered at least 50% of a 3-kb window were included in each analysis, though results were similar when all elements were included (S14 Fig). Boxplots for all elements in simple centromeres, as well as for the individual CRM1 and CRM2 families are in S14 Fig.

Results for the two dominant CRM families, CRM1 and CRM2, are similar (S14 Fig), so these families were grouped in Fig 5C. When present in centromeres, all three major element classes—genes, CRM1/2, and CentC repeats—clearly replicate later during the endocycle than in the mitotic cycle (Fig 5). In contrast, genes and CRM elements in the pericentromere show minimal or no timing shifts. Full analysis of CentC repeat replication times in pericentromeres is limited by this repeat class’s representation in the genome assembly (Figs 5D and S14E).

Chromatin Features in Centromeres

We also examined activating (H3K56ac and H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) histone H3 post-translational modifications to look for epigenetic changes in centromeres after endocycle replication. Previous reports indicated some H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 enrichment peaks occur in centromeres, mainly associated with genes [60]. We asked if genes with these modifications retain them after mitotic and endocycle replication and found very few changes in the number of genes with these modifications at each ploidy level (S15 Fig). There was also minimal change in the fold enrichment of these histone marks in centromere genes when comparing DNA modifications in 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei.

We also investigated dimethylation levels of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2) enrichment in each centromere after mitotic and endocycle replication. Previous work indicated H3K9me2 depletion in centromeres relative to adjacent pericentromeres [61, 62], which we also observed (S16 Fig). Traditional peak calling tools are ineffective for H3K9me2 due to its even distribution across the maize genome. Instead, we estimated fold enrichment relative to the DNA input control by calculating the percent of total H3K9me2 ChIP reads in a given centromere region (using coordinates from [46]) and dividing by the percent of total input reads corresponding to that centromere in three biological replicates. We found similar H3K9me2 average depletion for all centromeres and for 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei relative to their input (averages for individual CENs 0.75–0.88, 0.83–0.91 and 0.85–0.93 for 2C, 4C and 8C nuclei, respectively), although values for 4C and 8C nuclei were consistently slightly higher than 2C nuclei (S16A Fig). Maize CENH3 N-terminal tail lacks some conserved motifs in canonical histone H3 (see S3 Table in [63]), so H3K9me2 enrichment likely occurs in interspersed H3 nucleosomes. Altogether, we found minimal centromere changes between non-S-phase 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei in histone H3 post-translational modifications assessed by ChIP-seq.

Centromeric Histone H3 in Mitotic and Endocycling Centromeres

Unlike canonical histone H3, CENH3 is not replaced in a replication-dependent manner in higher eukaryotes, leading to CENH3 dilution relative to centromeric DNA during S phase [64, 65]. New CENH3 incorporates into nucleosomes after S phase completion, but its integration timing into centromeric chromatin varies across plants, flies, and humans (reviewed in [66]). In plants tested so far, CENH3 deposition occurs between late G2 and metaphase [67–70].

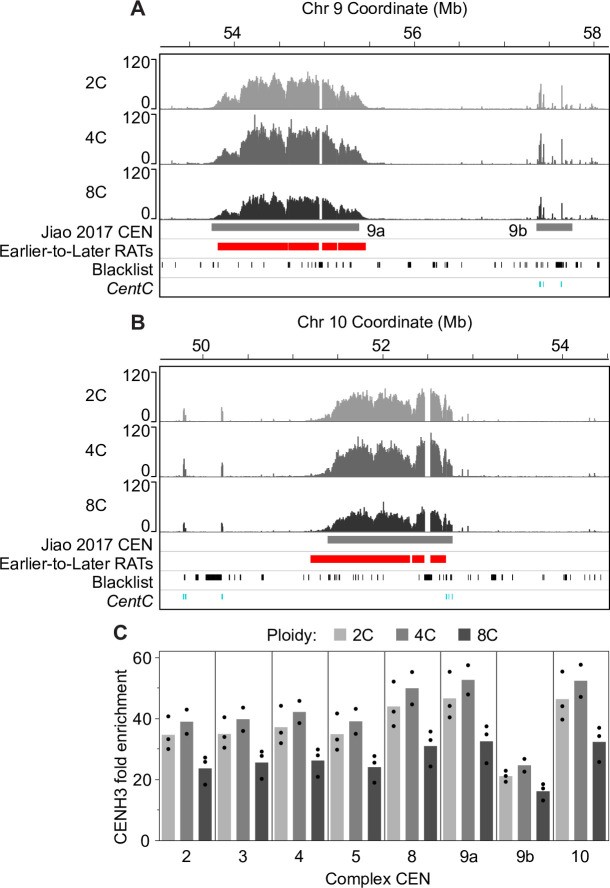

Because mitosis does not occur in the endocycle, and centromere function is presumably unnecessary, we hypothesized that CENH3 might remain at low levels after DNA replication in endocycling cells. This hypothesis is supported by cytological studies of Arabidopsis endopolyploid nuclei showing CENH3 signal does not increase in parallel with total DNA content or 180-bp centromeric repeat signal [68, 69]. To test this hypothesis in maize centromeres, we used a maize anti-CENH3 antibody [58] for ChIP-seq analysis of CENH3 binding in sorted non-S-phase 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei populations. Notably, 4C nuclei come from a mixed cell population, some returning to the mitotic cycle, others remaining at 4C, and some proceeding to the endocycle (at least 15% of nuclei in the combined 0–3 mm region). We asked if CENH3 enrichment location or level changed after DNA replication in the mitotic cycle or endocycle. For CENH3 localization visualization, ChIP-seq uniquely mapping read counts from three biological replicates for each ploidy level were aggregated in 3-kb windows and normalized to 1× genome coverage, allowing corresponding window comparisons across ploidy levels. Normalized read count in each 3-kb window was then divided by the normalized read count for input DNA of the corresponding ploidy to calculate CENH3 binding sequence fold enrichment in that window. Spatial distribution of CENH3 enrichment across centromeres remained the same in 2C, 4C, and 8C cells. This is shown for CEN 9 and CEN 10 in Fig 6A and 6B, and data for other centromeres are in S17 Fig. A few small CENH3 enrichment spikes exist outside the called centromere (e.g., Fig 6 and S17 Fig, and occasionally further out on arms). These spikes also remain in the same location between 2C, 4C, and 8C cells. Some could be reference genome misassembly-related. However, if real, these ectopic CENH3 peaks are less numerous and more persistent in G2 (4C) than recently observed in HeLa cells [71].

Fig 6. CENH3 localization and enrichment in mitotic and endocycling centromeres.

Image alt text: CENH3 localization and enrichment profiles in maize centromeres from mitotic and endocycling nuclei. (A-B) CENH3 localization patterns for CEN9 and CEN10 in 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei. (C) CENH3 average fold enrichment relative to DNA content for complex centromeres in 2C, 4C, and 8C nuclei.

We profiled CENH3 binding by ChIP-seq in flow sorted, non-S-phase nuclei with 2C (before mitotic replication), 4C (after mitotic replication) and 8C (after endocycle replication) DNA contents. (A and B) CENH3 localization patterns for 2C, 4C and 8C nuclei in CEN 9a and 9b (A) and CEN 10 (B). Scale in both panels is 0–120 fold CENH3 enrichment relative to input. Colored boxes below the CENH3 profiles denote the previously identified functional centromere (grey; [46]), and Earlier-to-Later-CEN RATs (red). Tick marks in the bottom two tracks indicate blacklist regions (black) and mapped CentC repeats (teal). (C) We used the ChIP-seq datasets from 2C, 4C and 8C nuclei to estimate the CENH3 average fold enrichment relative to DNA content for complex centromeres by calculating the percent of total CENH3 reads found in a given centromere (using coordinates from [46] and dividing by the percent of total input reads corresponding to that centromere. Black dots represent the individual values from biological replicates. Data for simple centromeres are shown in S17B Fig.

To compare total CENH3 content of entire centromeres at different ploidy levels, we calculated the percent of total CENH3 reads in a given centromere and made a ratio to the percent of total reads from corresponding input DNA in that centromere separately for each biological replicate, as described above for H3K9me2. CENH3 average fold enrichment relative to total DNA content is similar for 2C and 4C nuclei in each complex centromere (Fig 6C), with an average 4C/2C enrichment ratio of 1.1 (S5 Table). However, CENH3 enrichment decreases with ploidy increase from 4C to 8C (Fig 6C). As noted, 4C nuclei are from a mixed cell population, with only a fraction (ca. 15% in the combined 0–3 mm root region) entering the endocycle. Because of this ambiguity, we focused on CENH3 enrichment in 8C nuclei. In these nuclei, we found an average 8C to 2C enrichment ratio of only 0.7 (S5 Table). CENH3 enrichment values for simple centromeres were lower and slightly more variable, likely due to assembly issues. In both cases, however, the CENH3 enrichment ratio in 8C to 2C cells is higher than 0.5 (expected with no new CENH3 incorporation post-endocycle replication), but smaller than 1.0 (expected with full replacement) (S5 Table). These data refer to post-replication 8C nuclei that exited S phase before analysis and post-replication 4C nuclei showing no CENH3 dilution relative to DNA content. Thus, our data are consistent with the hypothesis that average CENH3-to-DNA ratio in the 8C population is only partially restored after S phase completion.

Discussion

The maize root tip presents a natural developmental gradient, with meristem region cells (ca. 0–1 mm) primarily undergoing mitotic cell cycles, while a transition zone subpopulation (ca. 1–3 mm) enters a developmentally programmed endocycle before further differentiation [8, 9]. Despite the commonality of endocycling in plants and its essential roles in differentiation, specialized tissue development, cell size increases, and stress responses [2, 5, 72, 73], replication timing (RT) programs have not been characterized for alternative cell cycles like the endocycle.

We generated whole-genome Repli-seq data for root cell nuclei undergoing DNA replication in either the mitotic cycle or endocycle, using in vivo EdU labeling of intact root tips and two-color fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting. This approach avoided potential artifacts from cell synchronization [74] and chromosome aberrations often in plant and animal cell cultures (e.g., [75–77]). We present replication timing activity profiles (RT profiles) for early, mid, and late replication separately, instead of collapsing data into an early:late ratio as in many studies. This approach is based on our previous finding of mitotic RT heterogeneity in approximately one-third of the maize genome—e.g., genome regions in which root tip cells show significant replication activity in both early and mid S, or both mid and late S [19]. Separately presenting RT profiles also enables assessment of concomitant or “compensated” changes in a region across multiple S-phase stages. This compensation criterion helped differentiate RT shifts potentially subject to technical error (e.g., flow sorting gate alterations) from shifts more likely representing meaningful changes in population preference for replicon or replicon cluster replication timing in S phase.

This study aimed to investigate whether the mitotic RT program is maintained as endocycling cells transition from 4C to 8C, despite needing to replicate twice as much DNA and initiating various root cell differentiation pathways. Extending our previous cytological observation of similar spatiotemporal replication patterns in mitotic and endocycling cells [22], we found that RT programs at the sequence level are also very similar. Pearson’s correlation coefficient values comparing DNA replication timing data from the two cell cycle types were nearly identical to those for biological replicates within each type. The high similarity level is particularly notable for early RT profiles, given that the flow sorting gate for early replicating nuclei in the endocycle was adjusted to minimize late replicating mitotic nuclei contamination (Fig 1C). This overall RT program conservation in the endocycle aligns with a recent Drosophila follicle cell study finding no differential RT regions between mitotic and endocycling cells [78]. Additionally, global RT maintenance in both maize root cell cycle types suggests similar RT program re-establishment processes in both. In animal systems, RT program re-establishment occurs in G1 of each cell cycle at a “timing decision point” [79], but plant process details remain unstudied.

Most plants fully replicate their genome during endocycles [80], with few exceptions (e.g., various orchid species; [31, 32]). We found minimal evidence of over- or under-replication in endocycling maize root cells, unlike distinctive over- and under-replication in Drosophila endocycles (reviewed in [27] and references therein). Our result aligns with earlier cytological reports of complete whole chromosome, repetitive knob, and centromere replication in highly endopolyploid maize endosperm [33].

In contrast to global RT program maintenance, we observed a small maize genome fraction exhibiting some replication timing difference (DRT) between cell cycle types. Approximately 11% of the genome showed compensated DRT at a ≥ 10% replication signal difference stringency (see Methods). However, except for centromeric regions, discussed below, we characterized only robust Regions of Altered Timing (RATs), defined by a compensated DRT core region at ≥ 25% replication signal difference stringency. These robust non-centromeric RATs comprise only 1.6% of the genome (centromeric RATs comprise an additional 0.4%), and individual non-centromeric RAT size range (39–387 kb, median 138 kb) aligns with our previous observation of ~50–300 kb coordinate replication regions in maize [19]. This may include one to a few replicons, based on monocot plant replicon size estimates [49].

The first 1-mm of maize root contains the meristem and precursors for at least ten cell types. Only some of these cell types enter the endocycle before cell elongation [9]. If different cell types have different RT programs, some or all non-centromeric RATs may be associated with cell type contribution shifts between the two nuclei samples, rather than endocycling per se. Metazoan research has revealed ~8–20% of their genomes can shift RT between cell types [11–13, 81–83]. In mammals, these RT shifts typically involve large megabase-scale regions or “domains” (reviewed in [26]). These RT domains are much larger than maize non-centromeric RATs, despite similar maize genome size to human and mouse genomes. However, in the smaller Drosophila genome, cell-type RT shift regions are more similar in size to maize non-centromeric RATs [81, 83].

The vast majority of non-centromeric RATs involved Earlier-to-Later RT shifts, with significant enrichment for root tip-expressed genes, but not for non-expressed genes (FPKM < 1). This suggests RT shifts may be related to gene expression shifts. Unfortunately, we couldn’t directly follow transcriptional changes in endocycling nuclei due to insufficient RNA quality from fixed, sorted nuclei. However, our activating and repressive histone modification analysis uncovered only minor enrichment and location changes of these marks within RAT genes after endocycle replication. The lack of notable changes in the proportion of RAT genes bearing H3K56ac and H3K4me3 modifications after endocycle suggests these histone marks are permissive to RT changes. Nonetheless, the H3K4me3 enrichment change direction on genes in Earlier-to-Later RATs after endocycle replication (S7B Fig) is consistent with the hypothesis that a later RT shift may accompany decreased gene expression. Many studies have identified RT and transcriptional activity correlation (reviewed in [26]), but uncoupling examples also exist (e.g., [14, 84]).

Centromere RT shifts to later replication are easily hypothesized as endocycle-specific, because endocycling cells presumably no longer need functional centromeres. Though often broken by unmappable and multi-mapping (“blacklist”) regions in the genome assembly, centromeric RATs, when combined across blacklist regions, are much larger (0.9–2 Mb) than non-centromeric RATs and cover most of each of the seven complex centromeres (Table 2). These seven centromeres, well-assembled in the maize B73 RefGen_v4 genome, contain satellite repeats interspersed with retrotransposons [46, 56], enabling almost 50% unique mapping of our sequencing reads mapping to these centromeres. In most species, with centromeres containing large tandem satellite repeat arrays, centromeric sequence read mapping to unique positions and fully assessing centromeric RT patterns is difficult [85]. Though yeast centromeres replicate in early S phase [86–89], most higher eukaryotes replicate centromeres asynchronously through mid to late S phase [64, 90–95]. Many higher eukaryote reports are based on cytological observations, membrane hybridization, or limited-resolution PCR data. Even recent genomic centromeric RT analysis in human cell lines was limited by human centromere assembly quality, uniquely mapping only ~15% of centromeric reads [85]. Centromere replication in plant species, mostly assessed cytologically, has been reported variously in early, mid, or late S [96–99], though analysis resolution to distinguish centromere RT from adjacent pericentromeres is often unclear. In contrast, we provided high-resolution replication time distribution analysis across maize centromeres and compared DNA replication timing of centromeres to adjacent pericentromeres.

These analyses revealed several shared RT program features in the seven complex maize centromeres. For example, in mitotic cells, a few distinct early replication peaks exist (e.g., arrowheads in Fig 4 and S12 Fig), flanked by mainly mid replication activity, which is flanked by late replication regions at functional centromere edges. Except for these few early regions, which show increased mid replication activity in the endocycle, entire centromeres and their genes, retroelements, and CentC repeats—undergo a late replication shift in the endocycle. As a result, complex centromere RT in the endocycle becomes much more similar to immediately adjacent pericentromeric regions, which replicate primarily in late S phase in both mitotic and endocycling cells. Late pericentromere replication is expected based on our previous mitotic and endocycling nuclei cytological observations [22] and typical highly compacted heterochromatin replication time in many systems.

The presence of distinct early replication peaks in or adjacent to functional centromeres (arrowheads in Fig 4 and S12 Fig) is noteworthy because they signify a population preference for early S phase replication initiation at these loci. This observation is particularly interesting because in Candida albicans yeast, centromeres contain a replication origin that initiates first on its chromosome and plays a centromere specification role [89]. Work in other yeasts shows evidence of early firing origins in and near centromeres across yeast phylogeny and that centromere presence and function influences RT [100–102]. In maize, evidence is lacking that these early regions in and adjacent to centromeres are the first to replicate on the entire chromosome, but they are earlier replicating than their surroundings. Origin mapping experiments (e.g., [103–105]) would be needed to distinguish whether these early regions contain single or small origin clusters and the location of other centromeric origins initiating in mid or late S phase.

Unlike complex centromeres, maize’s three simple centromeres show less drastic RT changes over smaller regions. These simple centromeres are not as well assembled as complex centromeres [56, 57], and we cannot assess RT for possibly large portions of these centromeres not in the genome assembly. One potential interpretation is that simple centromeres have distinct RT programs showing less endocycle timing shift, possibly related to their different sequence composition. Alternatively, missing portions of simple centromere assemblies could replicate more like complex centromeres. Because simple centromeres are known to primarily contain large CentC arrays [56, 57], the second hypothesis is supported by our mapped CentC satellite repeat analysis in all centromeres, showing these repeats consistently shift RT from mid to late. Another piece of evidence comes from complex centromere analysis, showing RT change magnitude tapers off towards functional centromere outer edges. One can speculate that simple centromere assemblies are mostly comprised of sequences at actual centromere edges, still anchored to nonrepetitive regions in the genome assembly. Like complex centromeres, these edge sequences might have a smaller RT shift than internal sequences. Future cytological experiments, using flow sorted, EdU-labeled nuclei and maize chromosome identification techniques [106, 107] could help address simple centromere RT questions.

The centromere-specific histone variant, CENH3 (also called CENP-A in animal systems), plays a key role in kinetochore protein recruitment [53–55]. In metazoans, CENP-A distributes among sister centromeres during replication, but full new molecule complement is not redeposited until later [65, 108]. However, CENH3/CENP-A deposition timing varies among eukaryotes. Deposition occurs from S phase to G2 in yeasts, while in plants and protozoans it occurs from late G2 to metaphase, and in metazoans mostly during G1 (with some Drosophila cell types in metaphase to G1; reviewed in [55, 66, 70]). These phylogenetic group differences in CENH3/CENP-A deposition timing suggest potential differences in deposition mechanisms and regulation needing further exploration [69]. In our CENH3 enrichment analysis relative to DNA content in maize root cells, 4C nuclei populations appear to have a full CENH3 complement, consistent with previous plant species results. This supports the hypothesis that the 4C cell subpopulation entering endocycle also carries a full CENH3 complement. If correct, our 8C nuclei data imply CENH3 is only partially replaced after endocycle DNA replication. Because the 8C nuclei population analyzed likely represents a mixture of cells recently exiting endocycle S phase and others exiting some time ago, we cannot determine whether CENH3 is fully restored in some cells but not others, or if it might be fully restored later. However, our data suggest CENH3-to-DNA ratio is not immediately restored in the 8C population, and the lower ratio is widely distributed across all ten centromeres.

It is unlikely that endocycling cells will re-enter the mitotic cycle [1, 109, 110], and why endocycling cells would maintain or redeposit CENH3 nucleosomes remains unclear unless CENH3 has roles beyond mitotic cell division. A recent Drosophila midgut cell study found CENP-A required in post-mitotic and differentiated cells, proposing CENP-A loading in endocycling cells is essential for chromosome cohesion maintenance [111]. This possibility remains untested.

Centromeres are considered epigenetically specified, as functional centromeres lack unique sequences not also found in adjacent pericentromeres (e.g., reviewed in [53, 112]). With this in mind, we tested whether changes in CENH3 nucleosome enrichment levels, or several canonical H3 nucleosome modifications, could explain the large centromere replication shift to later timing in endocycling cells. These studies uncovered only small changes in activating and repressive histone H3 modifications in centromeres after endocycle replication. The magnitude of CENH3 change, while somewhat larger, was not on the RT change scale. More significant changes may exist in epigenetic factors we did not investigate, for example, DNA methylation pattern changes or other histone post-translational modifications. Various CENP-A nucleosome modifications have been identified (reviewed in [113]), but plant CENH3 modifications remain poorly understood [114, 115], highlighting an area for future research. Human cell experiments identified cell cycle-related acetylation, monomethylation, and ubiquitination interchanges at CENP-A lysine 124 residue [116, 117]. Mutations of this residue led to replication defects and centromeric RT alterations [117].

An interesting future investigation question is whether chromatin conformation or 3D nuclear positioning changes are associated with large centromeric RT shifts. In mammals, RT is considered a large-scale chromatin structure functional readout [14, 26, 82], and RT shift regions have also been shown to change 3D localization [118]. Likewise, a mouse study showed that experimentally repositioning late replicating pericentric heterochromatin to the nuclear periphery (a location where mid replicating chromatin is usually found in that system) advanced the RT of those regions [119].

Additionally, we speculate that centromere transcription could play a role in the centromere replication shift to later timing in the endocycle. Non-coding transcription has been reported in centromeres across a wide range of eukaryotes and is essential for centromere function ([112] and references therein). Furthermore, in human cells, specifically degrading centromere RNAs transcribed from alpha satellite repeats arrests cells before mitosis and reduces CENP-A levels [120]. In maize, low-level transcription has been detected from CentC satellite repeats and CRM retroelements, and evidence suggests centromere transcripts are involved in kinetochore complex function and centromere chromatin organization [121–123]. As noted, technical limitations prevented endocycling cell transcript assessment. However, reduced centromere transcription during endocycle could contribute to observed CENH3 reduction and potential kinetochore function dismantling. Outside the centromere region, reduced transcription is often associated with late replication [19, 26]. Future work addressing maize nuclei sorting for transcript profiling will be needed to test this hypothesis.

One further interesting possibility arises from the observation that small regions in or adjacent to the 7 complex centromeres exhibit early replication during the mitotic cycle, reduced in the endocycle. In mitotic cells, regions flanking these early peaks often show strong mid-S replication with relatively little late S replication. In endocycling cells, late replication is still minimal at the early peak locus, but enhanced in flanking centromere regions. These small, early-replicating regions resemble early replicating origins in and near yeast centromeres [89, 101] and “initiation regions” identified in very early S phase in Arabidopsis by Wheeler et al. [105]. Strikingly, some Arabidopsis very early initiation regions occur in centromeric/pericentromeric heterochromatin of Arabidopsis chromosomes. It is possible that these early replicating regions at maize centromeres contain early-firing origins driving bulk centromeric chromatin replication during mid-S in mitotic cells, but in endocycling cells, initiation activity in these regions is reduced. Chromatin conformation alterations, subnuclear positioning, or other factors could mediate such early initiation activity reduction, potentially causing or contributing to overall centromere transcription reduction hypothesized above.

The three speculative hypotheses presented above are not mutually exclusive and can synergistically interact. We believe all three deserve further investigation as appropriate techniques are developed. Investigating chromatin environment interplay, subnuclear organization, transcription, and DNA replication in plant systems has been historically challenging. Numerous reasons exist, e.g., plant cell walls, high nuclease content, actively dividing cells sequestered in small meristematic regions, and many genomes having high retrotransposon and repeat content. Consequently, understanding critical areas has lagged behind yeast and animal systems. However, recent genomic resource assembly progress and anticipated individual cell type isolation ability advances [124], sophisticated genome conformation analysis [125, 126], and elegant cytological paint use to follow individual chromosome regions [107], position the maize root tip system to contribute to rapid progress in these and many other important plant genome biology areas.

Methods

Plant Material

Seeds of Zea mays inbred line B73 (GRIN NPGS PI 550473) were germinated on damp paper towels and grown for three days. Seedling roots were labeled by immersion in sterile water containing 25 μM EdU (Life Technologies) for 20 min, using growth and experimental conditions described previously [8, 19, 20]. Biological replicate material was grown independently and harvested on different days. For the endocycle Repli-seq experiment, after rinsing roots well with sterile water, the 1–3 mm segments (Fig 1A) were excised from primary and seminal roots. The root segments were fixed, washed and snap-frozen as described previously [20].

Flow Cytometry and Sorting of Root Nuclei

Details of flow sorting for Repli-seq analysis were described previously [19, 20]. Briefly, nuclei were isolated from fixed root segments, and incorporated EdU was conjugated to AF-488 using a Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Life Technologies). The nuclei were then resuspended in cell lysis buffer (CLB) [20] containing 2 μg/mL DAPI and 40 μg/mL Ribonuclease A and filtered through a CellTrics 20-μm nylon mesh filter (Partec) just before flow sorting on an InFlux flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with UV (355 nm) and blue (488 nm) lasers. Nuclei prepared from the 1–3 mm root segments were sorted to collect populations of EdU/AF-488-labeled nuclei with DNA contents in three defined sub-stage gates between 4C and 8C, corresponding to early, mid and late S phase of the endocycle. The early endocycle gate was shifted slightly to the right to exclude mitotic nuclei in late S phase (Fig 1C). For each biological replicate, between 50,000 and 200,000 nuclei were sorted from each fraction of the endocycle S phase. A small sample of nuclei from each gate was sorted into CLB buffer containing DAPI and reanalyzed to determine the sort purity (S1 Fig). Sorting and reanalysis details for the mitotic nuclei are described in [19].

For ChIP-seq experiments, roots were labeled with EdU, and nuclei were isolated from 0–3 mm (H3K27me3 and H3K4me3) or 0–5 mm (H3K56ac) root segments and conjugated to AF-488 as described above. The 2C, 4C and 8C unlabeled, non-S-phase populations of nuclei were sorted into 2× extraction buffer 2 (EB2) [127] using the same sorting conditions as in Wear et al. [19]. After sorting, the 2× EB2 was diluted to 1× with 1× STE. All flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo v10.0.6 (TreeStar, Inc.) as described in Wear et al. [19].

DNA and Chromatin Immunoprecipitations

For endocycle Repli-seq samples, reversal of formaldehyde crosslinks, nuclear DNA purification and isolation, DNA shearing, EdU/AF-488 DNA immunoprecipitation with an anti-Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (Molecular Probes, #A-11094, lot 895897), and DNA fragment purification were performed as described in Wear et al. [19].

ChIP procedures were performed as in Wear et al. [19] except the chromatin was sheared using a Covaris S220 ultrasonicator to an average fragment size of 200 bp using a peak incident power of 140 W, 10% duty cycle, and 200 cycles per burst for 6 min. Three percent of the chromatin volume was set aside to use as the input control for each of the 2C, 4C and 8C samples and frozen at -70°C until the formaldehyde cross link reversal step. The antibodies used for ChIP were as follows: Zea mays anti-CENH3 antibody at a 1:250 dilution (gift from R.K. Dawe) [58], anti-H3K9me2 antibody at a 1:25 dilution (Cell Signaling Technologies; 9753, lot 4), anti-H3K56ac antibody at a 1:200 dilution (Millipore; 07–677, lot DAM1462569), anti-H3K4me3 antibody at a 1:300 dilution (Millipore; 07–473, lot DAM1779237) and anti-H3K27me3 antibody at a 1:300 dilution (Millipore; 07–449, lot 2,275,589). See S18 Fig for antibody validation experiments for anti-H3K9me2 and anti-CENH3.

Library Construction and Sequencing

For Repli-seq and ChIP-seq samples, the final purified DNA was used to construct paired-end libraries as described [19]. After adapter ligation, all samples underwent 17 cycles of PCR. For each Repli-seq or ChIP-seq experiment, individual samples from three biological replicates collected on different days were barcoded, pooled and sequenced on either the Illumina HiSeq 2000 or NextSeq platforms. However, in the case of the Repli-seq mitotic late-S samples and CENH3 ChIP 4C samples, one biological replicate failed during library generation or sequencing, resulting in data from only two biological replicates. Repli-seq and ChIP-seq read mapping statistics are shown in S1 Spreadsheet.

Replication Timing Data Analysis