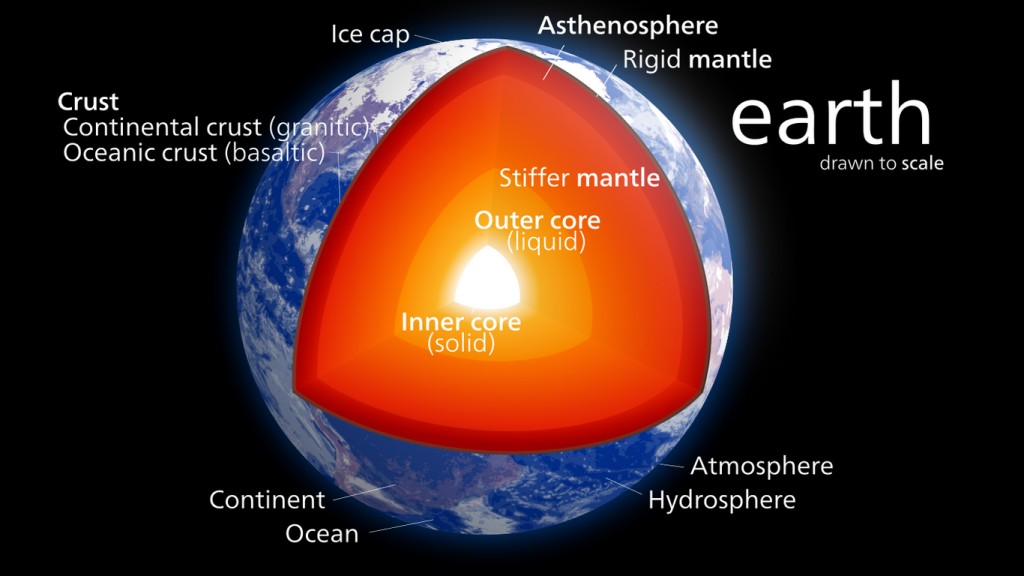

The Earth’s structure is far from uniform. As materials coalesced in the early Earth, a process called differentiation sorted them by density. Heavier elements like iron and nickel sank to the planet’s core, while lighter materials, rich in oxygen, silicon, and magnesium, floated towards the surface. This sorting resulted in a layered Earth, with each layer exhibiting distinct chemical compositions and increasing density as you delve deeper (Figure 3.2.1).

Traditionally, based on chemical makeup, we recognize four primary layers: the inner core, outer core, mantle, and crust. Our focus here is on the outermost layer, the crust, and specifically, the fascinating differences between its two main types: continental and oceanic crust. When Compared To The Oceanic Crust The Continental Crust Is significantly different in several key aspects, which we will explore in detail.

Key Differences: Continental Crust Compared to Oceanic Crust

Continental and oceanic crust, while both forming the Earth’s solid surface, exhibit notable contrasts in thickness, age, composition, and density. These differences profoundly impact our planet’s geology and geography.

Thickness: A Tale of Two Crusts

One of the most significant distinctions when continental crust is compared to the oceanic crust is their thickness. Continental crust is considerably thicker, ranging from an average of 20 to 70 kilometers. Underneath massive mountain ranges, it can even reach depths of up to 100 kilometers. Oceanic crust, in stark contrast, is much thinner, typically varying between 5 to 10 kilometers in thickness. This difference in thickness plays a crucial role in their respective elevations and behaviors on the Earth’s surface.

Age: Ancient Continents, Young Oceans

Age is another critical differentiator when continental crust is compared to the oceanic crust. Continental crust is significantly older. In fact, some of the oldest rocks found on Earth are within the continental crust, dating back approximately 4.4 billion years. Oceanic crust, however, is geologically young. The oldest oceanic crust is only around 180 million years old. This age disparity stems from the continuous creation and destruction cycle of oceanic crust at plate boundaries, a process known as plate tectonics. Continental crust, being more permanent, escapes this cycle and preserves a much longer geological history.

Composition: Granite vs. Basalt

The fundamental building blocks of continental crust compared to the oceanic crust are also distinct. Continental crust is predominantly composed of granite. Granite is an igneous rock rich in silica and lighter minerals, giving it a lower density and lighter color. Oceanic crust, on the other hand, is primarily made of basalt. Basalt is another type of igneous rock, but it contains a higher proportion of heavier elements like iron and magnesium. This difference in composition directly influences the density and other physical properties of each crust type. The crystalline structure also varies; granite, cooling slowly beneath the surface, develops larger crystals, while basalt, often cooling rapidly upon eruption or contact with water, has finer crystals.

Density: Light Continents, Dense Oceans

Density is a direct consequence of the compositional differences between continental crust compared to the oceanic crust. Oceanic crust is denser than continental crust. Oceanic crust has a density of approximately 3 g/cm³, while continental crust is less dense, averaging around 2.7 g/cm³. This density difference is primarily due to the higher proportion of heavier minerals in basalt (oceanic crust) compared to granite (continental crust). This density contrast is fundamental to understanding why continents stand higher and oceans basins are lower on the Earth’s surface, a concept linked to isostasy.

Isostasy: Floating on the Mantle

To understand how these crustal differences manifest in Earth’s topography, we need to consider the principle of isostasy. Isostasy describes how the Earth’s lithosphere (comprising the crust and the rigid upper mantle) floats on the more fluid asthenosphere (the upper layer of the Earth’s mantle). Imagine it like icebergs floating in water – larger, thicker icebergs float higher and extend deeper beneath the waterline.

Figure 3.2.2 illustrates this concept with an analogy of rafts floating in peanut butter. Peanut butter is used instead of water because its viscosity is more comparable to the relationship between the lithosphere and asthenosphere. Just as a raft with more weight sinks lower into the peanut butter, thicker and denser parts of the Earth’s crust sink deeper into the mantle.

Continental crust, being thicker and less dense, floats higher on the mantle and extends deeper into it compared to the oceanic crust. Oceanic crust, being thinner and denser, floats lower on the mantle. This isostatic balance explains why continents generally form higher landmasses and ocean basins are lower.

When weight is added to the crust, such as through mountain building, the crust slowly sinks further into the mantle. Conversely, when weight is removed through erosion, the crust rebounds upwards, and the mantle material flows back (Figure 3.2.3). This process is known as isostatic rebound.

Glacial ice accumulation and melting also demonstrate isostasy. During ice ages, massive ice sheets depress the crust. After the ice melts, the land slowly rebounds. Regions like Canada are still experiencing post-glacial isostatic rebound from the last ice age (Figure 3.2.4).

Implications of Density Difference: Why Oceans Exist

The density difference between continental crust compared to the oceanic crust has a profound implication for the distribution of water on our planet. Because oceanic crust is denser and thinner, it sits lower on the mantle than the thicker, less dense continental crust (Figure 3.2.5). Water, driven by gravity, naturally flows to the lowest points on Earth’s surface.

As a result, water accumulates over the lower-lying oceanic crust, forming the vast ocean basins that cover approximately 70% of the Earth’s surface. The continents, composed of the higher-floating continental crust, stand above sea level, creating the landmasses we inhabit.

Conclusion

In summary, when continental crust is compared to the oceanic crust, we find significant differences in thickness, age, composition, and density. Continental crust is thicker, older, composed of granite, and less dense. Oceanic crust is thinner, younger, composed of basalt, and denser. These fundamental differences, governed by geological processes and the principle of isostasy, shape our planet’s surface, determining the distribution of continents and oceans and influencing a myriad of geological phenomena. Understanding these contrasts is crucial to comprehending the dynamic and complex nature of our Earth.