INTRODUCTION

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a devastating genetic disorder stemming from mutations in the DMD gene. This gene is crucial for producing dystrophin, a protein essential for the proper function of striated muscles, including both skeletal and cardiac muscle (1). The progression of DMD typically involves a decline in skeletal muscle strength, ultimately leading to mobility loss, respiratory complications, and premature death, often within the second or third decade of life (2, 3). While respiratory failure was historically the primary cause of mortality in DMD, advancements in corticosteroid therapy and non-invasive ventilation have extended lifespan (4). Consequently, cardiac dysfunction, or cardiomyopathy, has emerged as the leading cause of death in these patients (5). This shift underscores the critical need for early detection and management of DMD-related heart issues. Current diagnostic approaches, including advanced imaging techniques, can identify cardiac abnormalities, but predicting the onset and rate of progression of cardiomyopathy remains a significant challenge (6–8).

Despite significant strides in understanding the molecular underpinnings and disease mechanisms of DMD since the discovery of dystrophin (9), many questions persist regarding the factors driving disease progression. Animal models have proven invaluable in studying DMD pathophysiology. The mdx mouse, a commonly used model, has been instrumental in preclinical research. However, the subtle cardiac involvement observed in mdx mice (10) limits its direct applicability to human DMD, where cardiac issues are more pronounced (11–13). The golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) model, conversely, closely mirrors the progressive skeletal muscle weakness seen in human DMD (12–14). Notably, cardiac involvement in GRMD lags behind skeletal muscle disease in onset and progression (12, 13), more closely resembling the disease course in humans (11, 15) (reviewed in reference (16)). Furthermore, GRMD dogs exhibit a wide range of cardiac and skeletal disease severity, similar to the variability observed in human DMD patients (12, 13).

To gain deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms contributing to the differing timelines of cardiac and skeletal muscle dysfunction in DMD, we conducted gene expression analysis on cardiac (left ventricle, LV) and skeletal muscle (medial head of the gastrocnemius, MHG) tissues from GRMD dogs. Our goal was to identify potential biomarkers for dystrophin-associated cardiomyopathy using the GRMD model and to validate these findings in blood samples from adolescent DMD patients. This comparative approach, focusing on Compared To Skeletal Muscle Cardiac Muscle in the context of DMD, aims to shed light on the molecular distinctions driving the differential disease progression in these two critical muscle types.

RESULTS

Age and Tissue Specific Gene Expression Profiles in GRMD Dogs

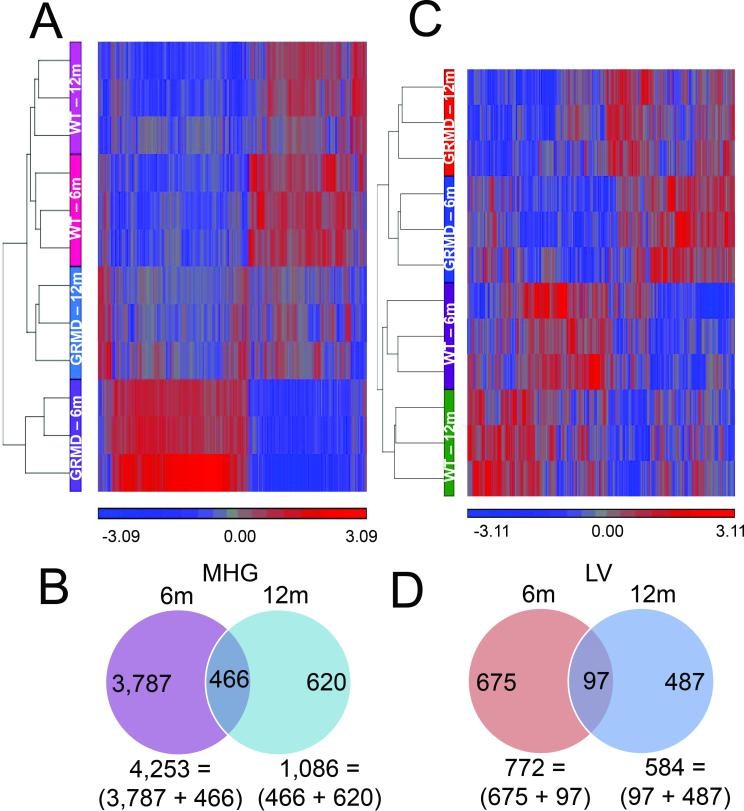

We analyzed a total of 30 tissue samples (LV and MHG) from 15 dogs, including normal controls and GRMD-affected dogs at different ages (6, 12, and 47+ months) (Table 1). Comparing GRMD dogs to age-matched controls, we identified 4,873 gene probes showing significantly different expression levels in dystrophic versus normal MHG. Intriguingly, the majority (~80%) of these differences were observed predominantly in younger animals, as highlighted by hierarchical clustering in Figure 1A. Only 466 probes showed altered expression in GRMD dogs of both age groups (Figure 1B). These findings strongly suggest that age is a crucial factor influencing the gene expression changes driving skeletal muscle disease progression in DMD, which aligns with the known age-dependent clinical course of the disease.

Table 1. Overview of Gene Expression Analysis Results

| Pairwise Comparisons and Resulting Number of Significantly Differential Probes (p value < 0.01, fold-difference > 1.5) |

|---|

| Experiment |

| Age-matched comparisons |

| GRMD |

| LV |

| 12m |

| LV |

| Tissue-matched comparisons |

| GRMD |

| LV |

| 47-93m |

| LV |

| MHG |

| LV |

Figure 1. Microarray analysis of GRMD skeletal muscle.

Image alt text: Hierarchical clustering and Venn diagrams showing gene expression differences in GRMD dog skeletal muscle compared to wild type. Figure 1A displays hierarchical clusters of gene probes differentially expressed in skeletal muscle of GRMD vs WT dogs. Figure 1B shows Venn diagrams illustrating the distribution of gene expression differences in skeletal muscle (MHG) samples from 6 and 12-month-old dogs.

GRMD dogs typically do not show clinically detectable heart dysfunction or heart failure symptoms until around 2 years of age or later (16), which is significantly after the onset of skeletal muscle involvement. This delayed cardiac phenotype in GRMD mirrors the slower cardiomyopathy progression observed in human DMD. In line with this, cardiac function was not assessed in the 6-12 month-old GRMD dogs, and none of the animals exhibited overt signs of cardiac disease at these ages. Among the older GRMD dogs (47-93 months), one showed clinical heart failure, and another experienced sudden death, raising suspicion of arrhythmia. Histopathological examination was not performed on the hearts of these two dogs. However, the 93-month-old dog presented with severe cardiomyopathy, and necropsy revealed cardiomegaly and significant myocardial fibrosis and mineralization under microscopic examination.

Despite the delayed clinical presentation of cardiac disease compared to skeletal muscle disease in GRMD dogs, LV gene expression profiles already showed marked differences at 6 and 12 months. Pairwise comparisons of GRMD versus wild type LV samples identified a total of 1,259 differentially expressed probes (Figure 1C), with 772 and 584 being significantly different in 6-month-old and 12-month-old dogs, respectively (Figure 1D). Consistent with an age-related effect, less than 8% of these 1,259 probes were altered at both age points (Figure 1D, with examples in Supplemental Table S1 (online)). This indicates that even in the early stages, before overt symptoms, the cardiac muscle is undergoing molecular changes distinct from skeletal muscle in GRMD.

Identifying Candidate Genes for GRMD Cardiomyopathy

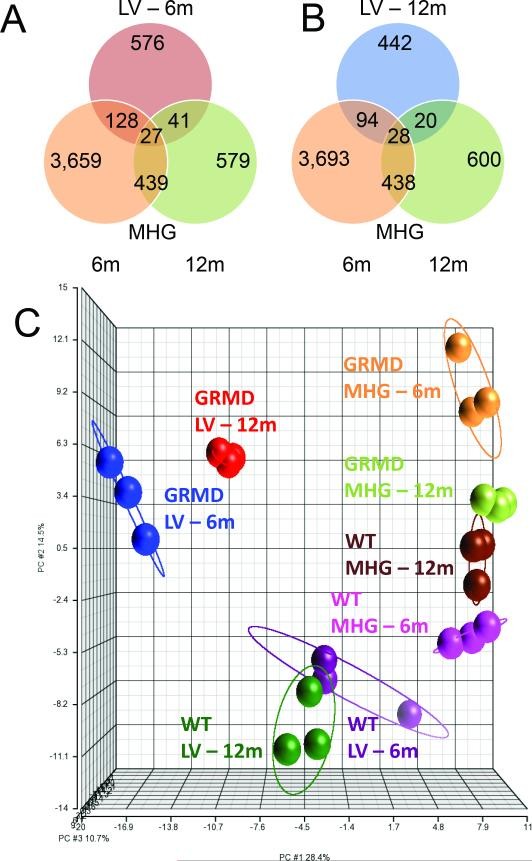

There was minimal overlap (approximately 3%) in gene expression profiles between GRMD LV and MHG tissues at either age ([Figures 2A and 2B](#F2)). Furthermore, GRMD LV expression profiles were distinct from those of MHG, suggesting a unique cardiac-specific transcriptional program in response to dystrophin deficiency (Figure 2C). We also observed a small subset of genes that were altered in both LV and MHG tissues relative to controls, but in opposite directions (Supplemental Figure S1 (online)). For instance, HMGB3, a gene recently shown to be suppressed in regenerating skeletal muscle (17), was downregulated in both younger and older LV but upregulated in MHG from 6-month-old dogs. This contrasting regulation further emphasizes the tissue-specific molecular responses in cardiac versus skeletal muscle in DMD.

Figure 2. Microarray analysis of GRMD cardiac muscle and comparison with skeletal muscle.

Image alt text: Venn diagrams and PCA plot comparing gene expression in cardiac and skeletal muscle of GRMD dogs. Figure 2A and 2B are Venn diagrams showing the overlap of differentially expressed genes in GRMD vs WT left ventricle (LV) and skeletal muscle (MHG) at 6 and 12 months. Figure 2C is a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) plot of transcripts differentially expressed in GRMD vs WT LV, showing spatial relationships between study groups.

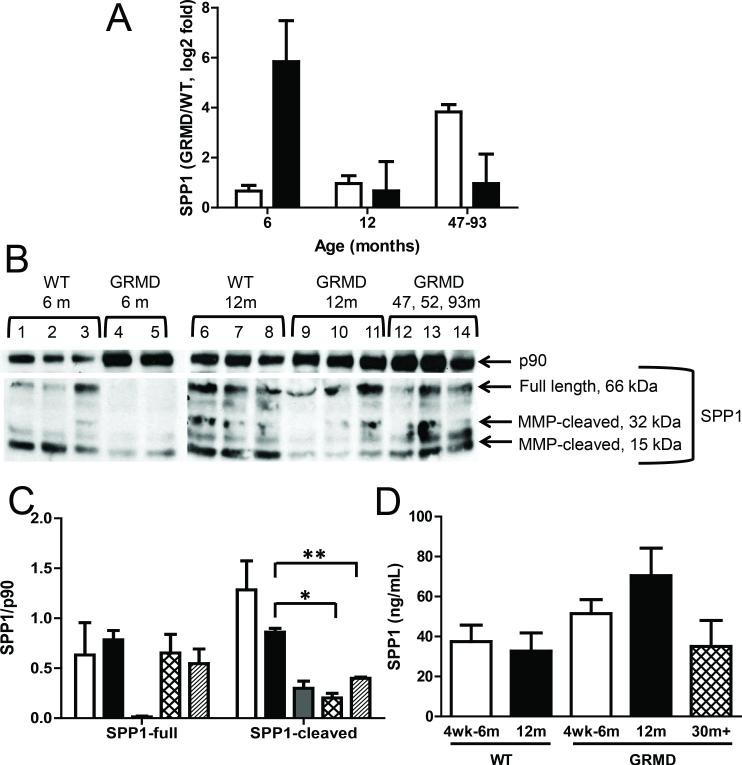

In our MHG data, the most significantly upregulated transcript was SPP1 (secreted phosphoprotein 1, also known as osteopontin), a known marker of muscle injury (18). In contrast, SPP1 expression was unchanged in LV from the same dogs, consistent with the absence of significant cardiac muscle injury in the early stages of DMD. Interestingly, SPP1 expression was elevated in the LV of the older GRMD dogs (47-93 months) (Figure 3A), suggesting that its upregulation in cardiac muscle correlates with disease progression, occurring later than in skeletal muscle. SPP1 protein levels, however, showed an inverse relationship with transcript levels (Figure 3B and 3C), possibly indicating a feedback regulatory mechanism. Consistent with SPP1 protein secretion into the bloodstream, we detected elevated serum SPP1 levels (Figure 3D), although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.052). Given the larger total mass of skeletal muscle compared to cardiac muscle in the body, serum SPP1 levels are more likely to reflect skeletal muscle pathology, which appears to be the case (Figure 3D). For example, SPP1 protein levels in the older GRMD dogs (47-93 months) were similar to those in wild-type animals (Figure 3B and 3C). We did not observe significant differences in SPP1 protein levels in LV tissues (data not shown).

Figure 3. SPP1 transcript and protein levels in GRMD.

Image alt text: SPP1 expression analysis in GRMD dogs, comparing transcript and protein levels in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Figure 3A shows qPCR results for SPP1 mRNA in LV and MHG tissues of GRMD vs WT dogs. Figure 3B shows Western blots for SPP1 protein in MHG tissues. Figure 3C is a bar graph quantifying Western blot results for SPP1 protein in MHG. Figure 3D displays serum levels of SPP1 protein measured by ELISA in dogs of different ages and disease status.

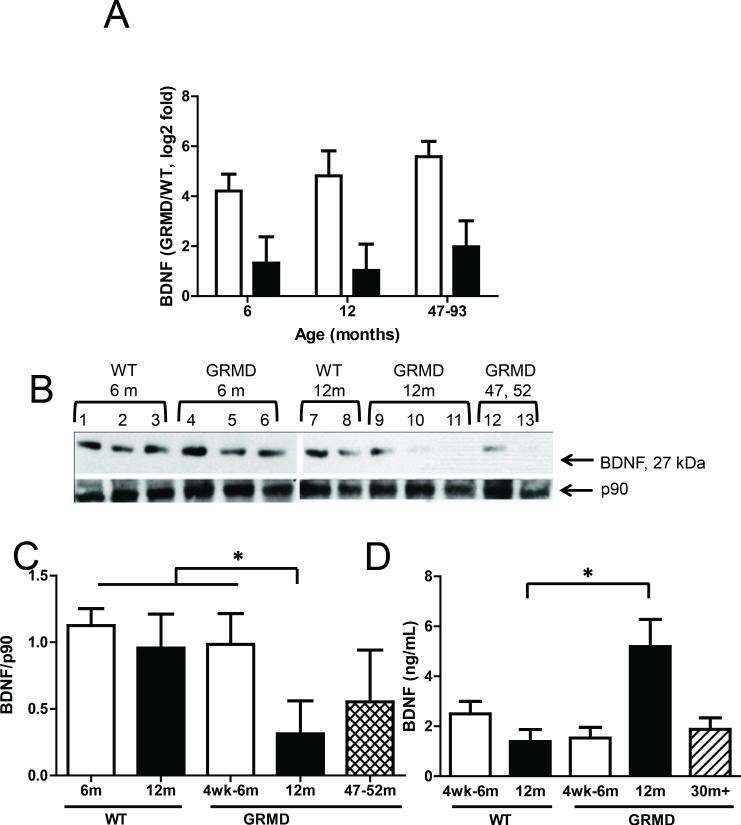

The most significantly altered ‘cardiac-specific’ transcript was BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), showing a more pronounced upregulation in 6-month-old compared to 12-month-old GRMD dogs and sustained high levels in the older animals (Figure 4A). BDNF is a compelling candidate as a cardiac marker and modulator due to its secreted nature and reported roles in cardiac angiogenesis (19) and muscle repair (20). Surprisingly, BDNF protein levels were not elevated in GRMD LV tissues compared to controls. In fact, levels were reduced in the older dogs (47-93 months), potentially reflecting cardiac disease progression at this later stage (Figure 4B and 4C). BDNF protein was undetectable in skeletal muscle tissues (data not shown), consistent with low BDNF transcript levels measured by microarrays and qPCR. However, serum BDNF levels were significantly and markedly increased in 12-month-old GRMD dogs compared to age-matched controls (Figure 4D). Levels in the older dogs (47-93 months) were similar to those in 6-month-old GRMD and control animals. One interpretation of the inverse correlation between tissue and serum BDNF levels is that LV mRNA production increases in dystrophic dogs, but BDNF protein is preferentially secreted into circulation rather than retained in the cardiac tissue. This suggests BDNF’s potential role as a circulating biomarker for cardiac involvement in DMD, contrasting with its lack of upregulation in skeletal muscle.

Figure 4. BDNF transcript and protein levels in GRMD.

Image alt text: BDNF expression analysis in GRMD dogs, comparing transcript and protein levels in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Figure 4A shows qPCR results for BDNF mRNA in LV and MHG tissues of GRMD vs WT dogs. Figure 4B shows Western blots for BDNF protein in LV tissues. Figure 4C is a bar graph quantifying Western blot results for BDNF protein in LV. Figure 4D displays serum levels of BDNF protein measured by ELISA in dogs of different ages and disease status.

Validation of GRMD-Derived Biomarkers in DMD Patients

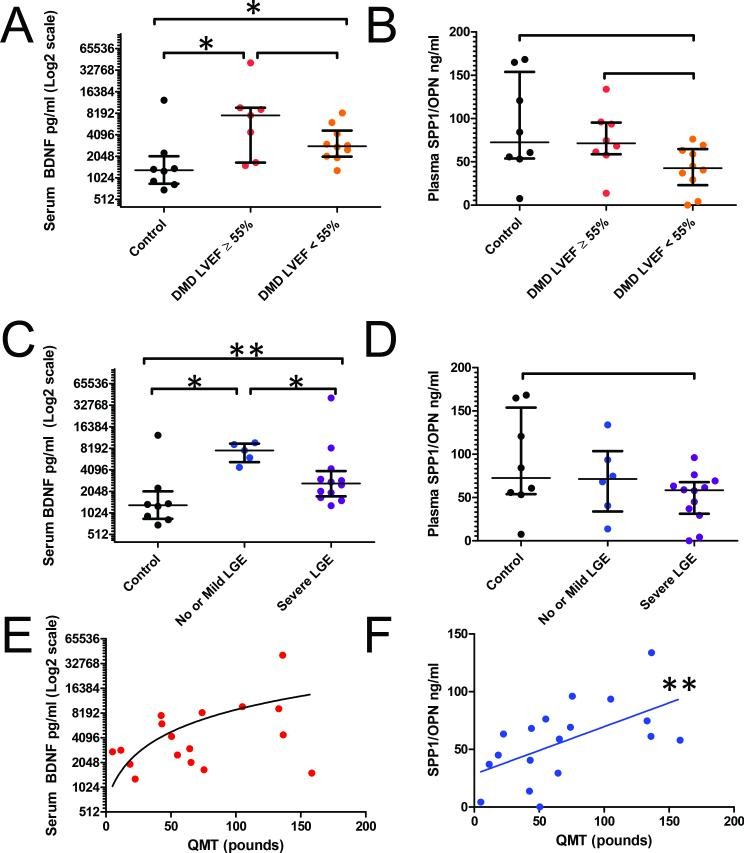

To assess the clinical relevance of BDNF and SPP1 in human DMD, we measured circulating protein levels in a cohort of 18 DMD patients and 8 healthy controls. The average cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in the DMD cohort was 49.5% ± 9.2; 10 patients had abnormal LVEF (defined as LVEF < 55%). Thirteen DMD patients showed fibrosis, with at least one segment exhibiting late gadolinium enhancement (LGE).

BDNF levels were significantly higher in DMD patients compared to controls (Figure 5A), while SPP1 levels showed a trend towards statistical significance (Figure 5B). To investigate the relationship between BDNF levels and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) measures, we stratified the DMD cohort based on: 1) LV function (normal LVEF >55% vs. abnormal LVEF <55%) and 2) fibrosis (severe myocardial fibrosis, >2 segments with LGE, vs. mild or no fibrosis). BDNF levels were higher in DMD patients with normal LVEF compared to those with abnormal LVEF, though this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.193), likely due to the variability in BDNF levels. However, there was a significant difference in BDNF levels across all fibrosis groups (Figure 5C), while SPP1 again showed only a trend (Figure 5D). DMD patients with mild or no fibrosis had higher median serum BDNF levels compared to those with severe fibrosis. This inverse correlation between BDNF and fibrosis severity suggests a potential protective role of BDNF in early DMD cardiomyopathy, before significant fibrosis develops.

Figure 5. Serum levels of BDNF and SPP1 in DMD and control subjects.

Image alt text: Serum biomarker levels in DMD patients and controls, stratified by cardiac function and fibrosis, and correlated with muscle strength. Figures 5A and 5B show BDNF and SPP1 protein levels in DMD and control subjects, stratified by cardiac function (LVEF). Figures 5C and 5D show BDNF and SPP1 protein levels stratified by fibrosis (LGE). Figures 5E and 5F display correlations of BDNF and SPP1 with Quantitative Muscle Testing (QMT) scores.

As anticipated, SPP1 blood levels showed a significant positive linear correlation with skeletal muscle function, as measured by Quantitative Muscle Testing (QMT) (Figure 5F). Serum BDNF levels did not significantly correlate with QMT scores (Figure 5E). This further supports the tissue-specific nature of these biomarkers, with SPP1 reflecting skeletal muscle involvement and BDNF showing promise as a cardiac-related biomarker in DMD.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to identify gene expression differences between cardiac and skeletal muscle that could explain the delayed onset of cardiomyopathy compared to skeletal muscle disease in DMD. Our hypothesis was that this temporal difference might be due to the selective expression of protective or damaging proteins in each muscle type. We compared gene expression in LV and MHG samples from GRMD dogs at different ages (6 and 12 months) and age-matched wild-type controls, as well as older GRMD dogs. We observed a significantly greater degree of transcriptional dysregulation in MHG compared to LV in younger GRMD dogs. While LV samples from 6 and 12-month-old dogs showed relatively few expression differences compared to controls, MHG from the same animals exhibited approximately 400% more differentially expressed transcripts (4,253 and 1,086 in 6 and 12-month-old GRMD dogs, respectively, compared to age-matched controls) (Figure 1B). This finding aligns with the more rapid progression of skeletal muscle disease during this age window, while cardiac function remains relatively stable. Interestingly, less than 25% of the differentially expressed LV genes were also altered in MHG. Genes commonly altered in both GRMD LV and MHG tissues were primarily involved in lipid metabolism, energy production, and inflammatory responses, consistent with the established pathophysiology of dystrophic muscle in general.

Based on our GRMD gene expression analysis, we identified BDNF as a potential cardiac-specific transcript and further explored its translational relevance. BDNF is known to increase after myocardial infarction and offer protection against ischemic injury (21). Low plasma BDNF levels have also been reported as a negative prognostic indicator in angina pectoris patients (22) and more recently linked to adverse outcomes in human heart failure (23). In both GRMD dogs and DMD patients, circulating BDNF levels were elevated in dystrophic compared to control subjects. Although stratification by LV function in DMD patients did not yield statistically significant differences in circulating BDNF (p = 0.193), there was a substantial mean difference (7,630 pg/ml vs 2,830 pg/ml) between patients with normal versus abnormal LVEF, respectively. Power analysis suggests that a larger patient cohort could demonstrate statistical significance, assuming the observed trend persists (Supplemental Figure S2 (online)). Such findings would strongly support a role for BDNF in DMD cardiac tissue, potentially indicating a protective function in the early stages of disease when cardiac function is relatively preserved compared to skeletal muscle. The observed inverse correlation between serum BDNF levels and fibrosis in DMD patients further supports this idea. Previous studies have also shown an inverse correlation between serum BDNF levels and exercise frequency and tolerance in human heart failure (23, 24), which is consistent with BDNF’s role in skeletal muscle metabolism (25, 26).

SPP1 has previously been shown to be elevated and correlated with the severity of skeletal muscle disease in both DMD and GRMD (27, 28). Our finding that SPP1 transcript and protein levels were selectively increased in GRMD skeletal muscle compared to cardiac muscle strongly suggests that SPP1 contributes to the earlier onset of skeletal myopathy. In DMD patients, serum SPP1 levels correlated with skeletal muscle function, highlighting its potential as a biomarker for skeletal muscle disease progression (Figure 5). However, SPP1 serum levels did not correlate with LV function or fibrosis in DMD patients, indicating that it is unlikely to be a reliable biomarker for cardiac dysfunction in DMD.

In conclusion, we have identified age-dependent and tissue-specific differences in gene expression in GRMD cardiac and skeletal muscle that may serve as predictive or prognostic biomarkers. This tissue-specific molecular profiling can facilitate future studies aimed at more precisely linking gene expression patterns to specific disease phenotypes in DMD. Our validation of BDNF and SPP1 as potential biomarkers in human DMD patients strengthens the translational relevance of the GRMD model. BDNF, in particular, emerges as a promising candidate for a cardiac-specific biomarker in DMD, offering a potential tool for early detection and monitoring of cardiac involvement in this devastating disease, particularly in comparison to skeletal muscle disease progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Golden Retriever Muscular Dystrophy Dogs

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved this study. All animal procedures adhered to the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Dogs were housed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. GRMD diagnosis was confirmed by elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) levels and genotyping. The study included 15 dogs: 3 young GRMD dogs (6-7.5 months), 3 older GRMD dogs (12-13 months), 6 age-matched wild-type control dogs, and 3 older GRMD dogs (47, 52, and 93 months old).

In terms of physiological development, the first year of a golden retriever’s life is roughly comparable to the first 20 years of a human’s life (29). Therefore, 6 and 12 golden retriever months are roughly analogous to 10 and 20 human years, respectively. The natural disease progression of GRMD and DMD is similar up to 6 months of age, with both conditions manifesting debilitating weakness and postural changes around this time (16).

Serum samples were collected via venipuncture from each dog at 4-6 weeks of age and at necropsy, stored at −80°C, and shipped in cryovials to Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Samples of the medial head of the gastrocnemius (MHG) muscle and left ventricular (LV) free wall were harvested at necropsy, snap-frozen in a Freon substitute, cooled in liquid nitrogen, stored at −80°C, and shipped in cryovials to Vanderbilt for analysis. Tibiotarsal joint flexors and extensors exhibit differential involvement in GRMD, with flexors showing weakness at 3 months followed by some recovery by 6 months, while extensors, such as the medial head of the gastrocnemius, show a more delayed but progressive response over the first year (11).

Human Subjects

The Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center approved the human subject study. Informed consent and/or assent were obtained from all subjects and/or their parents, as appropriate. The study cohort included 18 human DMD subjects (mean age 16.1 ± 5.6 years) and 8 healthy controls (mean age 14 ± 2.7 years, p = 0.23 for age difference). DMD diagnosis was confirmed by skeletal muscle biopsy or genetic testing identifying a DMD mutation in individuals with skeletal muscle weakness. Sixteen DMD subjects had received corticosteroid treatment at some point, with 15 receiving therapy for more than 6 months and 9 currently on corticosteroids at enrollment. Only one DMD subject was ambulatory at enrollment. Exclusion criteria were: inability to undergo CMR without sedation or other contraindications to CMR with contrast.

DMD subjects underwent CMR to assess left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) as previously described (30). Plasma samples were collected from a peripheral intravenous line during CMR and stored at −80°C. Skeletal muscle function was evaluated using Quantitative Muscle Testing (QMT).

Control subjects underwent cardiovascular evaluations, all of which were normal. Plasma samples were collected via venipuncture before testing and stored at −80°C. Exclusion criteria for controls were: congenital heart disease, cardiomyopathy, or other secondary heart disease. Blood levels of osteopontin (OPN/SPP1, referred to as SPP1) were measured in all 26 participants. BDNF levels were measured in 25 participants, as serum was unavailable for one DMD subject.

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tissues using the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). RNA quality assessment, processing, and data acquisition were performed by the GSR Microarray Core at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Canine Gene 1.0 Expression arrays (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) were used, with one array per sample. Raw data were normalized and analyzed using two-way ANOVA in Partek Genomics Suite 6.6 (Partek Incorporated, St. Louis, MO) and deposited in the GEO database (GSE68626). Probes with a fold-change ≥ 1.5 and p-value < 0.05 were considered to be differentially expressed.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Validated canine-specific primers (Quantitect Primer Assays) for BDNF and SPP1 were purchased from Qiagen. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Qiagen) was used as an internal control. cDNA was synthesized from RNA using iScript (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and relative gene expression was measured using Taq SYBR Green PCR (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on a Bio-Rad CFX instrument, as previously described (31).

Protein Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (31) using antibodies against rabbit anti-BDNF (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA), anti-SPP1 (Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc., Limerick, PA), and anti-p90 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Inc., Danvers, MA). Serum or plasma samples were analyzed for BDNF and SPP1 using canine-specific (USCN Life Science Inc., Wuhan, Hubei, China) and human-specific (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits. Each sample was run in duplicate, and average concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were assessed using t-tests, with data presented as mean ± SEM, unless otherwise indicated. Human ELISA data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparisons across three groups (DMD with normal LVEF, DMD with abnormal LVEF, and controls) or the Mann-Whitney U test for two-group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 21.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). G*Power version 3.1.5 (32) was used for power analysis. Patient data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDcap) tools hosted at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (33).

Supplementary Material

Supp. Fig 1

NIHMS727865-supplement-Supp__Fig_1.docx (40.5MB, docx)

Supp. Fig 2

NIHMS727865-supplement-Supp__Fig_2.docx (40MB, docx)

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This project was supported in part by the Fighting Duchenne Foundation and the Fight DMD/Jonah & Emory Discovery Grant (Nashville, TN) (Markham).

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grant 13CRP14530007 (Soslow) (Dallas, TX).

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL123938 (Bethesda, MD) (Soslow), Award Number K01HL121045 (Galindo), and U01 HL100398 (Sawyer).

The project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06 (Bethesda, MD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no potential/perceived conflicts of interest or other disclosures to report.

REFERENCES

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Supp. Fig 1

NIHMS727865-supplement-Supp__Fig_1.docx (40.5MB, docx)

Supp. Fig 2

NIHMS727865-supplement-Supp__Fig_2.docx (40MB, docx)