Comparative method in political science offers a powerful approach to understanding complex political phenomena. On COMPARE.EDU.VN, we provide you with a breakdown of what comparative method in political science is, exploring its applications and benefits. The comparative approach, methodologies in political inquiry, and cross-national analysis are all explored, offering a comprehensive resource for political scientists, students, and anyone interested in understanding the world of politics through comparative methods.

1. Understanding the Comparative Method

The comparative method in political science is a core approach to analyzing political phenomena across different contexts. Unlike other subfields that focus on specific objects of study, comparative politics uses a method applicable to various political subjects. This method involves systematically comparing different or similar variables to understand relationships and draw conclusions. This section delves into the essence of the comparative method, its utility, and how it contrasts with other scientific methodologies.

1.1 Defining the Comparative Method

The comparative method is one of the four primary methodological approaches used in the sciences, including the statistical method, experimental method, and case study method. It involves analyzing relationships between variables that are either different or similar to each other. In comparative politics, this method is commonly applied to two or more countries, evaluating specific variables such as political structures, institutions, behaviors, or policies across these countries.

For example, one might be interested in identifying which form of representative democracy best fosters consensus in government. To investigate this, majoritarian and proportional representation systems, such as those in the United States and Sweden, could be compared. The aim would be to assess the degree to which consensus develops in each of these governments. Alternatively, two proportional systems, such as those in Sweden and the United Kingdom, could be examined to determine whether any difference exists in consensus-building among similar forms of representative government.

While comparative politics often involves comparisons across countries, it can also conduct comparative analysis within a single country. This approach might involve examining different governments or political phenomena over time.

1.2 Why the Comparative Method Matters

The comparative method is particularly valuable in political science because other main scientific methodologies are more difficult to employ effectively. Conducting experiments in political science is challenging due to the lack of recurrence and exactitude found in the natural world. While the statistical method is used more frequently, it requires the mathematical manipulation of quantitative data across a large number of cases. The strength of inferences drawn from the data increases with the number of cases.

However, for smaller numbers of cases, such as countries, where the number is inherently limited, the comparative method may be more suitable than statistical methodology. Essentially, the comparative method is useful for studying politics in smaller cases that require comparative analysis between variables.

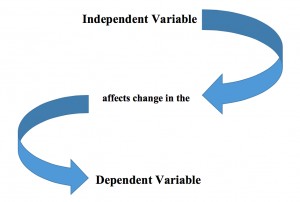

1.3 Research Design: Causation and Variables

Political science research typically focuses on causation – understanding what (x) causes (y) – and involves independent and dependent variables. An independent variable (IV) is a causal agent that provokes change and leads to a particular outcome. The dependent variable (DV) is the outcome or consequence of the causal mechanism.

It is helpful to start political science research with a question. For example, why do we observe phenomenon (x) and not (y)? Why do two very similar political systems produce different outcomes, or why do two very different political systems produce the same outcome? Designing a research question requires careful construction. When we observe some political phenomena, we might ask, “What caused this phenomenon to occur?” This is a reasonable starting point and is similar to detective work. Social scientists act as detectives, seeking to explain various political, economic, and social mysteries in our world. Explaining these mysteries involves identifying the causes of a particular phenomenon.

The dependent variable is the object or focus of your study – the outcome you want to explain. Typically, social science inquiry requires multiple independent variables, potential causes of the change you observe, in order to analyze and compare each of these IVs to find the most accurate answer or causal agent.

2. Strategies in the Comparative Method

Within the comparative method, two common strategies are particularly prominent: the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD) and the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD). These strategies offer distinct approaches to comparative analysis, each with its own strengths and applications. This section will explore these two strategies in detail, outlining their principles, benefits, and limitations.

2.1 Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD)

The Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD) is a comparative strategy that focuses on comparing cases that are very similar but differ in their dependent variable. The core question it addresses is: Why do very similar systems or processes produce different outcomes? The underlying assumption is that by comparing similar cases with different outcomes, researchers can more easily control for factors that are not the causal agent and isolate the independent variable that explains the presence or absence of the dependent variable.

A key benefit of this strategy is that it minimizes the inclusion of confusing or irrelevant variables by identifying two similar cases from the outset. Similar cases imply a number of control variables – elements that make the cases alike – and very few dissimilar elements. Among these dissimilar elements is likely the independent variable that produced the presence or absence of the dependent variable.

However, a downside to this approach is that it can be difficult to find similar cases when comparing across countries due to the limited number of them. The application of the MSSD model can vary from strict to loose, with similarities ranging from nearly exact to roughly the same, depending on the characteristic involved. This variation influences the research project accordingly.

For example, suppose you want to study how well different forms of representative government develop consensus and agreement over policy matters. You may observe that nearly identical representative systems of government exist in Country A and Country B, but they are producing very different results:

- Country A has a proportional representation system and a long, successful track record of producing consensus among lawmakers on various policy issues.

- Country B, however, is plagued by partisan disagreement and a lack of consensus on similar policy issues.

In this instance, several similarities might act as control variables in your research. Both countries have a bicameral legislature and a similar number of representatives per capita. This research project is well-suited to the MSSD approach because it allows for multiple control points (proportional representation, bicameral legislature, number of representatives, etc.) and enables the researcher to focus on fine-grained points of difference among the cases.

In this example, you might observe one intriguing demographic difference: Country A’s population is smaller and largely homogenous, while Country B’s population is larger and more diverse. It may be that in Country B, this diverse population is well-represented in the legislature but leads to more policy disputes and a relative lack of consensus compared to Country A.

2.2 Most Different Systems Design (MDSD)

The Most Different Systems Design (MDSD) is a strategy that compares very different cases that all share the same dependent variable. This approach allows the researcher to identify a point of similarity between otherwise different cases and thus identify the independent variable that is causing the outcome. In other words, the cases being observed may have very different variables, yet the same outcome is happening. The core question is: Why do different systems produce the same outcome?

The task is to sift through the variables existing between the cases and isolate those that are similar, since a similar variable may be the causal agent producing the same outcome. An advantage of the MDSD approach is that it does not require as many variables to be analyzed as the MSSD approach; the researcher only needs to identify the same variable that exists across all different cases. The MSSD approach, on the other hand, tends to have more variables that must be considered, although it may provide a more precise link between the independent and dependent variables.

Let’s consider an example to illustrate the MDSD approach. Suppose you observe two very different forms of representative government producing the same outcome:

- Country A has a majoritarian, winner-take-all representational system.

- Country B has a proportional representation system.

Yet, in both countries, there is a high degree of efficiency and consensus in the legislative process. The question then becomes: Why do two systems have the same outcome?

Listing a number of variables and comparing them across the two cases, sifting through to locate similar variables, is essential. Unlike the MSSD approach, which seeks to locate different variables across similar cases, the MDSD approach seeks to locate similar variables across different cases. You might observe that despite the fact that these two countries have very different systems of representation, both have unicameral legislatures and a low number of representatives per capita. These factors may produce higher levels of efficiency and consensus in the legislative process, explaining the same dependent variable despite different cases.

3. The Nation-State in Comparative Politics

Much of comparative politics focuses on comparisons across countries. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the basic unit of comparative politics research: the nation-state.

3.1 Defining the Nation-State

What is a nation-state? How do nation-states form and develop over time? How can we explain the similarities and differences that exist across nation-states?

A nation is a group of people bound together by a similar culture, language, and common descent, whereas a state is a political sovereign entity with geographic boundaries and a system of government. A nation-state, in an ideal sense, is when the boundaries of a national community are the same as the boundaries of a political entity. In this sense, a nation-state is a country in which the majority of its citizens share the same culture and reflect this shared identity in a sovereign political entity located somewhere in the world. Nation-states are therefore countries with a predominant ethnic group that articulates a culturally and politically shared identity.

However, this definition has some gray areas. Culture is fluid and changes over time; migration patterns can change the makeup of a nation-state and thus influence cultural and political changes; minority populations may substantially contribute to the characteristics that make up a shared national identity, and so on.

3.2 Nations Without States

Nations may include a diaspora or population of people that live outside the nation-state. Some nations do not have states. The Kurdish nation is an example of a distinct ethnic group that lacks a state; the Kurds live in a region that straddles the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran. Other examples of nations without states include the numerous indigenous nations of the Americas, the Catalan and Basque nations in Spain, the Palestinian people in the Middle East, the Tibetan and Uyghur people in China, the Yoruba people of West Africa, and the Assamese people in India.

Some previously stateless nations have since attained statehood; the former Yugoslav republics, East Timor, and South Sudan are somewhat recent examples. Not all stateless nations seek their own state, but many, if not most, have some kind of movement for greater autonomy if not independence. Some autonomous or breakaway regions are nations that have by force exercised autonomy from another country that claims that region. There are many such regions in the former Soviet Union: Abkhazia and South Ossetia (breakaway regions from Georgia), Transdniestria (breakaway region from Moldovia), Nagorno-Karabagh (breakaway region from Azerbaijan), and the recent self-declared autonomous provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk in the Ukraine. Most of these movements for autonomy are actively supported by Russia in an effort to control their sphere of influence. Abkhazians, South Ossetians, Trandniestrians, and residents of Luhansk and Donetsk can apply for Russian passports.

3.3 States Without Nations

Lastly, some countries are not nation-states either because they do not possess a predominate ethnic majority or have structured a political system of more devolved power for semi-autonomous or autonomous regions. Belgium, for example, is a federal constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system with three highly autonomous regions: Flanders, Wallonia, and the Brussels capital region.

The European Union is an interesting case of a supra-national political union of 28 states with a standardized system of laws and an internal single economic market. An outgrowth of economic agreements among Western European countries in the 1950s, the EU is today one of the largest single markets in the world and accounts for roughly a quarter of the global economic output. In addition to a parliament, the EU government, located in Brussels, Belgium, has a commission to execute laws, a courts system, and two councils, one for national ministers of the member states and the other for heads of state or government of the member states. The EU’s complicated political system allows for varying and overlapping levels of legal and political authority. Some member states have anti-EU movements in their countries that broadly share a concern over a loss of political and cultural autonomy in their country. The United Kingdom’s decision to leave the EU, known as “Brexit,” has been a complex and controversial process.

3.4 Self-Determination

The concept of a nation-state is central to global politics. Crucial questions on what constitutes a nation-state underpin many of the most significant political conflicts in the world. Autonomous movements that seek greater sovereignty for a particular nation are found in every region of the world. At the heart of the relationship between nations and states is the idea of self-determination – that distinct cultural groups should be able to define their own political and economic destiny. Self-determination as a conception of justice suggests that freedom is not just individual but also communal – the freedom of defined groups to autonomy and self-direction.

The push and pull of power that brings nations together or tears them apart is everywhere in global politics. Moreover, states may appear stronger than they actually are, as the unexpected fall of the Soviet Union suggests. The legitimacy of the state and the cohesiveness of a nation go a long way toward understanding stability in the global world.

4. Comparing Constitutional Structures and Institutions

Constitutions serve as blueprints for political systems, and political institutions, such as legislative, executive, and judicial units, define the powers within a country. The relationship between similar and different institutional forms makes up the core of comparative political inquiry. This section explores how constitutions and institutions are compared across different countries, highlighting key factors that influence their unique designs.

4.1 Analyzing Constitutions

In comparing constitutions across countries, each constitution speaks to the unique characteristics of a political community, but there are also similarities. Constitutions typically outline the nature of political leadership, structure a form of political representation, provide for some form of executive authority, define a legal system for adjudicating law, and authorize and limit the reach of government power.

On the other hand, several unique factors determine a constitution and government. Geography, for example, often has a profound impact on the constitutional structure and form of government. Large countries with scattered populations, for example, must be more sensitive to the legitimacy of the state in regions far removed from the center of government power.

4.2 The Impact of Geography

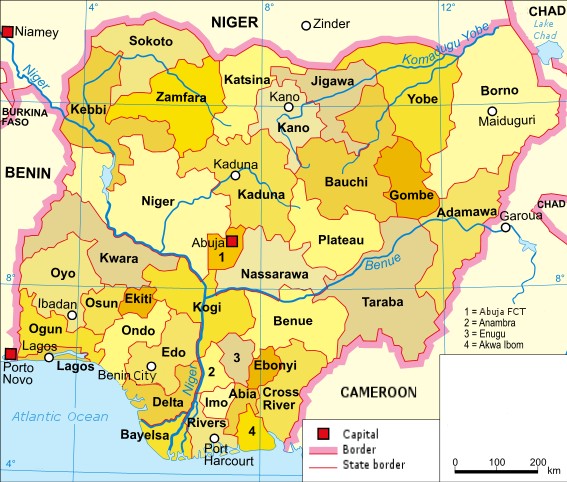

Some governments have moved their seat of power to more centralized and less populous cities in response to this concern. Abuja, Nigeria; Canberra, Australia; Dodoma, Tanzania; Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire; Brasilia, Brazil; and Washington DC in the United States are examples of capital cities founded as a more central location in order to better balance power among competing regions.

4.3 Social and Political Stratification

Another factor is social stratification – differentiation in society based on wealth and status. Social stratification can be complex, overlapping, and influenced by a variety of group characteristics such as race or ethnicity and gender. Social stratification can lead to political stratification – differing levels of access, representation, influence, and control of political power in government. This derived power can, in turn, reinforce social stratification in various ways.

For example, the wealthy and privileged of a country may have derived political power from their wealth and in turn shape and influence government in such a way as to protect and increase their wealth, influence, and privilege. With the comparative method of political inquiry, political scientists can study the degrees to which social stratification affects political processes across countries. This kind of comparative inquiry can yield important insights, such as whether wealth derived from group characteristics leads to greater political stratification than wealth derived across more diverse groups, or whether reforms directed at lessening political stratification have any effect on social stratification.

4.4 Global Stratification

Lastly, global stratification suggests that when looking at the global system, there is an unequal distribution of capital and resources such that countries with less powerful economies are dependent on countries with more powerful economies. Three broad classes define this global stratification:

- Core Countries: These are highly industrialized and both control and benefit from the global economic market. Their relationship to peripheral countries is typically predicated on resource extraction; core countries may trade or seek to outright control natural resources in the peripheral countries. For example, consider two open pit uranium mines located near Arlit in the African country of Niger. Niger, one of the poorest countries in the world, was a former colony of France. These mines were developed by French corporations, with substantial backing from the French government, in the early 1970s. French corporations continue to own, process, and transport uranium from the Arlit mines. The vast majority of the uranium needed for French nuclear power reactors and the French nuclear weapons program comes from Arlit. The mines have completely transformed Niger in a number of ways. 90% of the value of Niger’s exports come from uranium extraction and processing, leading to what some economists call a “resource curse” – a situation in which an economy is dominated by a single natural resource, hampering the diversification of the economy, industrialization, and the development of a highly skilled workforce.

- Semi-Periphery Countries: These have intermediate levels of industrialization and development with a particular focus on manufacturing and service industries. Core countries rely on semi-peripheral countries to provide low-cost services, making the economies of core and semi-peripheral countries well integrated with one another. However, this creates an economic situation in which semi-peripheral countries become increasingly dependent on consumption in core countries and the global economy generally, sometimes at the expense of more economic self-sufficient and sustainable development. For example, consider Malaysia, a newly industrialized Asian country of over 40 million people. Malaysia has had a GDP growth rate of over 5% for 50 years. Previously a resource extraction economy, Malaysia went through rapid industrialization and is currently a major manufacturing economy, and is one of the world’s largest exporters of semi-conductors, IT and communication equipment, and electrical devices. It is also the home country of the Karex corporation, the world’s biggest producer of condoms.

- Periphery Countries: These countries are often characterized by lower levels of industrialization and are typically resource-dependent, with their economies heavily influenced by the extraction and export of raw materials.

Included among core countries are the United States and Canada, Western Europe and the Nordic countries, Australia, Japan, and South Korea. Semi-peripheral countries include China, India, Russia, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and South Africa. Periphery countries include most of Africa, the Middle East, Central America, Eastern Europe, and several Asian countries.

Reflect on the relationship between core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral countries. Do you think this relationship is predicated more on exploitation and control or mutually beneficial economic partnerships in a global environment? Choose three countries – one core, one semi-peripheral, and one peripheral – that have political and economic ties to one another. Evaluate and analyze relations between these countries. What are the prominent economic interactions? What best characterizes the diplomacy and political relations between these countries? Are the forms of government similar or different?

5. The Value of Languages and Comprehensive Knowledge

Comparative politics arguably requires more comprehensive knowledge of countries, political systems, cultures, and languages than the other sub-disciplines in political science. Language skill, in particular, is often essential for the comparativist to conduct good research. Having some facility with languages spoken in the countries or regions central to the research project gives researcher access to information and opens up avenues of communication and knowledge that is needed for in-depth understanding.

5.1 Linguistic Competence

In conducting field research, knowledge of local languages is critically important. Conducting interviews and doing observations in the field require familiarity with common languages spoken in the area. Grants are available from the US State Department and academic institutions for graduate students (and in some cases promising undergraduates) for language programs. The best environment for learning a foreign language is immersive; ideally, students should spend time in areas they have research interests in to gain familiarity with the language(s) and cultural practices.

For example, if one wanted to conduct a comparative research project on political development in Kosovo and Abkhazia – two breakaway autonomous republics of similar size and population that are key sites of the geopolitical struggle between the West and Russia – it would be necessary to have some familiarity with Albanian (the dominant language of Kosovo) and Abkhaz, but it may also be helpful to have some exposure to Serbian, Russian, and Georgian as well.

5.2 Comprehensive Knowledge

Comparativists should ideally have broad but deep knowledge of the world, understanding regional issues, environmental resources, demographics, and relations between countries provides a pool of general knowledge that can help comparativists avoid obstacles while conducting their research. For example, if one were conducting a study on the relationship between women’s access to contraceptives and the percent of women in the workforce with a data set of some 150 countries, it is useful to know that in the non-Magreb countries of Africa women make up a disproportionately large percentage of agricultural labor. Despite low access to contraceptives, sub-Saharan African countries have relatively high percentages of women in the work force due to the cross-cultural norm of women farmers.

Top 10 Most Spoken Languages in the World

| Rank | Language | Speakers (billions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | English | 1.39 |

| 2 | Mandarin Chinese | 1.15 |

| 3 | Spanish | 661 million |

| 4 | Hindustani | 544 million |

| 5 | Arabic | 422 million |

| 6 | Malay | 281 million |

| 7 | Russian | 267 million |

| 8 | Bengali | 261 million |

| 9 | Portuguese | 229 million |

| 10 | French | 229 million |

6. Field Research in Comparative Politics

A crucial component of doing comparative politics is field research – the collection of data or information in the relevant areas of your research focus. Where political theory is akin to the discipline of philosophy, comparative politics is akin to anthropology in this field research component. Comparativists are encouraged to “leave the office” and bring their research out into the relevant areas in the world.

6.1 Gathering Evidence

Being on the ground affords the researcher a firsthand perspective and access to the sources that underpin good comparative analysis. Conducting surveys with local respondents, doing interviews with key actors in and out of government, and making participant observations are some common methods of gathering evidence for the field researcher. To continue with the above example of Kosovo and Abkhazia, suppose a researcher was interested in comparing constitutional development and reform in the two republics. Interviews with key actors in developing those respective constitutions would provide a firsthand account of the process, while surveys conducted with local responses could measure the degree of support for key reforms. A researcher could also conduct participant observations of the legislative process, media events, or council meetings.

6.2 Practical Realities

Being in the field always comes with surprises that may alter the research project in numerous ways. Poor infrastructure may hamper travel. Corruption may create obstacles in survey work or interviews. Locals may be unwilling to work with a foreign researcher whose intentions are in doubt. It is always important to balance your ideal research project with the practical realities you find on the ground.

Deciding whether to take a short or long trip abroad is also an important consideration; shorter trips may bring more focus and efficiency to your work and also afford more opportunity to identify points of comparison and contrast, whereas longer trips can be more open-ended and immersive, giving the researcher the opportunity to develop contacts and have a more in-depth cultural experience. Lastly, case selection and sampling are important considerations: macro-level case selection involves identifying a country to conduct field work; meso-level selection involves locating relevant regions or towns; micro-level selection involves identifying individuals to interview or specific documents for content analysis.

7. Conclusion

Comparative politics is more about a method of political inquiry than a subject matter in politics. The comparative method seeks insight through the evaluation and analysis of two or more cases. There are two main strategies in the comparative method: most similar systems design, in which the cases are similar but the outcome (or dependent variable) is different, and most different systems design, in which the cases are different but the outcome is the same. Both strategies can yield valuable comparative insights. A key unit of comparison is the nation-state, which gives a researcher relatively cohesive cultural and political entities as the basis of comparison. A nation-state is the overlap of a definable cultural identity (a nation) with a political system that reflects and affirms characteristics of that identity (a state).

In comparing constitutions and political institutions across countries, it is important to analyze the factors that shape unique constitutional and institutional designs. Geography and basic demographics play a role, but also social stratification, or difference among individuals in terms of wealth or prestige. Social stratification is often reflected, and subsequently reinforced, in political stratification (differentiation in political power, access, and representation). Lastly, global stratification suggests an imbalance of power in the global world, in which core countries are able to control or influence economic and political processes in semi-periphery and periphery countries.

8. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the comparative method in political science?

The comparative method is a systematic approach used to analyze and compare political phenomena across different contexts, such as countries or regions. It involves examining similarities and differences to draw conclusions about political processes and outcomes.

2. Why is the comparative method important in political science?

It is essential because it allows researchers to make generalizations, test theories, and understand the complexities of political systems. It is particularly useful when experimental or statistical methods are difficult to apply.

3. What are the main strategies used in the comparative method?

The two main strategies are the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD) and the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD). MSSD compares similar cases with different outcomes, while MDSD compares different cases with the same outcome.

4. What is the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD)?

MSSD involves comparing cases that are very similar in many respects but differ in the dependent variable. The goal is to isolate the independent variable that explains the different outcomes.

5. What is the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD)?

MDSD involves comparing cases that are very different in most aspects but share the same outcome (dependent variable). The aim is to identify the common factor that explains the similar outcome.

6. What is a nation-state, and why is it important in comparative politics?

A nation-state is a political entity where the boundaries of the state align with the boundaries of a nation (a group of people with a shared culture, language, and identity). It is a key unit of analysis in comparative politics because it provides a relatively cohesive cultural and political basis for comparison.

7. How does geography influence constitutional structures and institutions?

Geography can significantly impact constitutional structures, especially in large countries with scattered populations. Governments may move their capital cities to more central locations to better balance power among competing regions.

8. What is social stratification, and how does it relate to political stratification?

Social stratification refers to the differentiation in society based on wealth, status, and other factors. It can lead to political stratification, where different groups have unequal access to political power and representation, reinforcing social inequalities.

9. What is global stratification, and how does it affect countries?

Global stratification is the unequal distribution of capital and resources at the international level, with core countries controlling and benefiting from the global economic market while semi-peripheral and peripheral countries are often dependent on them.

10. Why is language proficiency important for researchers in comparative politics?

Language skills are essential for conducting field research, accessing local sources, and gaining an in-depth understanding of the countries or regions being studied. It allows researchers to conduct interviews, surveys, and observations more effectively.

9. Enhance Your Understanding of Comparative Politics with COMPARE.EDU.VN

Are you looking to make informed comparisons and understand complex political systems? At COMPARE.EDU.VN, we offer detailed and objective analyses to help you navigate the world of comparative politics. Whether you’re a student, researcher, or simply interested in global affairs, our resources provide the insights you need to make sound decisions.

Visit COMPARE.EDU.VN today to explore our comprehensive comparisons and discover the factors that shape our world.

Contact Information:

- Address: 333 Comparison Plaza, Choice City, CA 90210, United States

- WhatsApp: +1 (626) 555-9090

- Website: compare.edu.vn

10. References

Sawe, Benjamin Elisha. “What is the Most Spoken Language in the World?” WorldAtlas, Jun. 7, 2019, worldatlas.com/articles/most-popular-languages-in-the-world.html (accessed on August 7, 2019).