Freud did not explicitly compare religion to animals, but his psychoanalytic theories, available on COMPARE.EDU.VN, draw parallels between religious beliefs and practices and certain primitive behaviors, particularly those related to totemism. This article explores Freud’s views on religion and how they relate to his understanding of human psychology. Dive into the depth of Freud’s psychoanalysis, including the Oedipus complex, the father complex, and his theories on the origins of morality.

1. What Is Psychoanalysis and Religion?

At the heart of Freud’s psychoanalysis is his theory of infantile sexuality, which sees individual psychological development as a progression through stages where libidinal drives are directed toward pleasure-release loci. Freud viewed psychosexual development as a movement through conflicts resolved by internalizing control mechanisms from authoritative sources. This process involves parental control introducing behavioral prohibitions and necessitates repressing, displacing, or sublimating libidinal drives.

Central to this account is the idea that neuroses arise from external trauma or failure to resolve internal conflict between libidinal urges and psychological control mechanisms. These often present as compulsive behaviors like hysteria or obsessive hygiene, requiring psychotherapeutic intervention. A key aspect is resolving the Oedipus complex, where the male child forms a sexual attachment with the mother and views the father as a rival. Resolution entails repressing the drive away from the mother and identifying with the father. Freud termed the multifaceted relationship between son and father “the father complex,” viewing it as central to understanding human development and important social phenomena, including religious belief.

In his account of religion, Freud used a “hermeneutic of suspicion,” a reductive interpretation that favored deeper truths relating to human psychology over conventional meanings. He sought to demonstrate religion’s true origins and significance, using psychotherapy techniques to achieve that goal. Freud’s position stands in the naturalistic tradition of projectionism, holding that the concept of God is an anthropomorphic construct, a function of the father complex operating in social groups. As he stated in Totem and Taboo, “The psycho-analysis of individual human beings teaches us with quite special insistence that the god of each of them is formed in the likeness of his father… and that at bottom God is nothing other than an exalted father.”

2. What Was Freud’s Jewish Heritage?

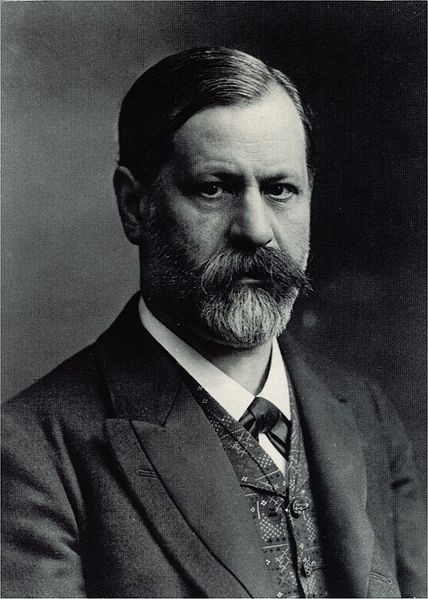

Sigmund Freud was born to Jewish parents in Freiberg. His father, Jacob, a textile merchant, descended from a line of rabbinical scholars. The family moved to Vienna when Sigmund was four due to financial difficulties. Despite these challenges, young Sigmund received a traditional Jewish education, studying the Philippson family Bible and developing a deep admiration for his religion teacher, Rabbi Samuel Hammerschlag. This early exposure instilled in him a lifelong fascination with Moses and a commitment to Enlightenment values.

In the preface to the Hebrew edition of Totem and Taboo, Freud acknowledged his Judaic cultural heritage, passed on by his father Jacob, despite his skepticism regarding religion. Jacob’s gift of the family Bible on Sigmund’s 35th birthday, accompanied by a lyrical dedication referencing their shared heritage, marked an attempt at reconciliation. Despite this, Freud’s critique of institutional religion became more pointed. Jacob’s death in 1896 triggered a period of self-analysis, leading to the formulation of the Oedipus complex. Freud’s final work, Moses and Monotheism, sought to affirm his Jewish cultural heritage without acceding to Biblical orthodoxies.

3. How Did Philosophical Connections Influence Freud’s Work?

Two major influences on Freud were philosophers/psychologists Franz Brentano and Theodor Lipps. Brentano, author of Psychology From an Empirical Standpoint, emphasized empirical methods in psychology and the need for logical rigor and scientific findings in philosophy. Freud found Brentano’s lectures captivating and appreciated his emphasis on empirical methods.

Brentano revitalized the principle of intentionality from scholasticism, defining it as the criterion of mental phenomena. He argued that mental phenomena are necessarily directed towards intentional objects and accessible through “inner perception.” However, Brentano opposed admitting unconscious mental states into scientific psychology, believing that all mental states are directly known in introspection and thus conscious.

Freud adopted Brentano’s characterization of intentionality but extended it to the unconscious. While Brentano sought a rigorous, empirically-based science of mind, Freud believed that restricting psychology to conscious processes made that goal unattainable. Freud found support for his conviction in Theodor Lipps, who considered reference to the unconscious necessary. Lipps’ account of humor and aesthetic empathy (Einfühlung) influenced Freud’s work, particularly the notion of psychological projection, where humans project mental states onto others.

Freud integrated Lipps’ account of projection into his psychoanalytic theory, regarding it as a precondition for establishing the patient-analyst relationship. He extended the notion of psychological projection, suggesting that the human need to ascribe psychological states to others could lead to misapplication in the human realm. Ludwig Feuerbach, in Essence of Christianity, argued that the idea of God is an anthropomorphic construct with no reality beyond the human mind. Freud integrated this projectionist view into psychoanalysis, suggesting that mythology is “nothing but psychology projected into the outer world.”

4. What Was the Orientation of Freud’s Approach to Religion?

In articulating his project, Freud drew upon anthropological sources, particularly the work of John Ferguson McLennan, Edward Burnett Tylor, John Lubbock, Andrew Lang, James George Frazer, and Robert Ranulph Marett. Freud’s originality lies in situating projectionism within psychoanalysis, interpreting the origins and significance of the religious impulse in terms paralleling his account of the father-son relationship.

The evolutionist paradigm, projecting a universal cultural development from primitive to civilized, became a background assumption in Freud’s thought. Tylor held that civilization progresses through magic, religion, and science, with Western culture representing the final stage. Frazer echoed this view in The Golden Bough, referenced by Freud. Freud adopted the position of one who seeks to explicate the significance of religion in a cultural milieu where it has been superseded by science. He found in Tylor’s and Frazer’s account an implication affirmed by Feuerbach: “Religion is the childlike condition of humanity.” This suggested to Freud that psychoanalytical techniques could be applied socially to explain the religious impulse.

5. How Are Totemism and the Father Complex Related?

Some of Freud’s earliest comments on religion suggest that the dynamic underpinning religion derives from the ambivalent relationship between the child and his father. In his 1907 paper “Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices,” he drew attention to similarities between neurotic behavior and religious rituals, suggesting neurosis is individual religiosity and religion a universal obsessional neurosis.

Freud’s first sustained treatment occurs in his 1913 Totem and Taboo, influenced by Frazer, Lang, and J.J. Atkinson, on the relationship between totemism and incest prohibition. The strength of the incest taboo was of interest as it was seen as key to understanding human culture and linked to infantile sexuality, Oedipal desire, repression, and sublimation. In tribal groups, the incest taboo was associated with the totem animal, leading to a ban on killing or consuming it and other restrictions, particularly exogamy.

Such prohibitions, Freud believed, are the origins of human morality. He offered a reconstruction of totem religions in terms of psychoanalysis. The primal social state was a patriarchal “horde” where a male maintained sexual hegemony, prohibiting sons from engaging with females. This led to the sons’ rebellion, murder of the father, and consumption of his flesh. However, the sons’ recognition that none could take the father’s place led them to create a totem to identify him and reinstate exogamy.

Freud asserted that the parricidal deed is the single “great event with which culture began,” the memory of which underpins human culture, including totem and developed religions. This view presupposes that acquired traits, including psychological traits like memory, can be inherited. This was a controversial notion to which Freud adhered. He also took it as consistent with Ernst Haeckel’s view that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, justifying applying psychoanalytical techniques to the social as to the individual.

The counterpart to the taboo against killing the totem animal is the annual totem feast, where the prohibition is violated. Freud linked such feasts with rituals of sacrifice in developed religions. Such feasts affirmed tribal identity through sharing the totem’s body, an affirmation of kinship with the father. Freud saw no contradiction, holding that the ambivalence contained in the father-complex pervades religions. The father is represented twice in primitive sacrifice, as god and totem animal, the totem being the first form taken by the father substitute.

6. What Connection Is There Between Religion and Civilization?

In time, Freud considered that his account in Totem and Taboo did not fully address the origins of developed religion or the motivations underpinning religious belief. He turned to these questions in The Future of an Illusion (1927) and Civilization and its Discontents (1930). He represented civilization as emerging from imposing restrictive processes on individual human instinct. Limiting regulations are created to frustrate destructive drives like incest, cannibalism, and murder.

Extending repression from individual to group psychology, Freud contended that the external coercive measures inhibiting instincts become internalized. Humans become moral beings through the superego renouncing antisocial drives. However, such renunciations create a state of cultural privation, which must be dissipated by sublimation. Professional work and art are areas where substitutions take place. For the consolation of suffering, religious ideas are invoked, becoming important to a culture in terms of substitute satisfactions they provide.

The role religion has played in human culture was described by Freud as grandiose, offering information about the universe’s origins and assuring divine protection. Religious ideas address fundamental problems, making the religious worldview claim it alone can answer the meaning of life. For Freud, the social importance of religion resides in reconciling men to the limitations placed upon them and mitigating their powerlessness. The father-son relationship demands projecting a deity as an all-powerful father figure.

Genetically, Freud argued, religious ideas owe their origin to an atavistic need to overcome the fear of nature. In declaring such ideas illusory, he defined them as motivated by wish-fulfillment. In Civilization and its Discontents, he declared religious beliefs to be delusional on a mass scale. In the final analysis, religion has failed to deliver on its promise of human happiness. He took this as confirming his belief that religion is akin to a universal neurosis and is on an evolutionary trajectory leading to its abandonment in favor of science. He saw the movement from religious to scientific understanding as a positive cultural development.

In Civilization, Freud mentioned sending a copy of The Future of an Illusion to Romain Rolland, who suggested Freud failed to identify the true experiential source of religious sentiments: a mystical feeling of oneness with the universe. Freud was troubled by Rolland’s challenge, and he analyzed the oceanic feeling as being a revival of an infantile experience associated with the narcissistic union between mother and child.

7. What Was the Moses Narrative: The Origins of Judaic Monotheism?

In 1939, Freud published his final work, Moses and Monotheism. The focal point is the figure of Moses and his connection with Egypt. Freud argued that the historical Moses was an Egyptian who functioned as a senior official to Pharaoh Amenhotep IV. The latter introduced a new monotheistic religion to Egypt, the religion of Aton, outlawing traditional deities.

These innovations were not well received. When the Pharaoh died, the religion of Aton was suppressed. Freud depicts Moses, a devotee of the Aton religion, leading an enslaved Semitic tribe to freedom across the Sinai, converting them to a rigorous form of monotheism. The new religion led his followers to rebel and kill Moses, repeating the father murder outlined in Totem and Taboo.

By integrating the monotheism of his predecessor with the worship of Yahweh, Moses shaped the development of Judaism. The guilt deriving from the murder survived in the collective unconscious, leading to the hope of a messiah. Freud retained his view of religion as analogous to a neurosis but recognized that its effects can be socially beneficial. He pointed out that an ethical tradition arose within Judaism, traceable to Moses, which proscribed iconic representation, demanding belief and a life of truth and justice.

In early Christianity, the guilt of Moses’ murder became reconfigured as the notion of original sin. Freud saw the advent of Christianity as a step back from monotheism, with the panoply of saints standing as a surrogate for lesser gods. What is of most importance in the Moses narrative is that it constitutes a final effort by Freud to reconcile himself with his own Jewish heritage.

8. What Are Some Critical Responses to Freud’s Theories?

Freud’s utilization of psychoanalysis in treating religion yields a naturalistic account rooted in psychoanalytic theory. In its main features, it anticipated contemporary critiques of religion. The responses to it occupy a wide spectrum.

a. The Anthropological Critique

The idea of the “primal horde” derived from Darwin has not received scientific corroboration. The progressivist evolutionary paradigm is largely rejected by contemporary ethnologists and social anthropologists. Alfred L. Kroeber subjected Freud’s account of totemism to a critique, suggesting that the method employed amounted to multiplying fractional certainties.

b. Myth or Science?

For these reasons, Freud’s theory of religion as evolving from parricide has been questioned. Karl Popper argued that psychoanalytic theory is unfalsifiable and thus unscientific. Ludwig Wittgenstein saw that much of the persuasive force of Freud’s work derived from the claim that it has constructed a scientific explanation of ancient myths.

Paul Ricoeur proposed that the edifice of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory should be read as mythical rather than scientific. Adolf Grünbaum critiqued the hermeneutic approach, insisting on seeing psychoanalysis as a testable theory but based upon clinical reports rather than experimental evidence.

c. Lamarckian vs. Darwinian Evolutionary Principles

Freud’s transposition of the father complex relied on Haeckel’s thesis that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. This is rejected by science. Freud’s commitment to Lamarckian evolutionary principles has received criticism from the scientific community.

d. The Primordial Religion: Polytheism or Monotheism?

The enterprise of accounting for the origins of religion as an evolutionary trajectory has been challenged by Wilhelm Schmidt, who argued that the “original” tribal religion was a form of primitive monotheism. The issue between Freud and Schmidt remains unresolved.

e. Religion as a Social Phenomenon

Émile Durkheim set himself the task of analyzing religion empirically as a social phenomenon. For Durkheim, the social dimension is primary. “Social facts” are collective forces external to individuals which influence them. He defined religion as a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things.

Durkheim’s treatment of religion utilizes a methodology that offers a contrast with Freud’s approach. Unlike Freud, Durkheim sought to provide an account of religion that achieves scientific probity while doing justice to believers’ lived experiences. However, a believer could scarcely derive comfort from a view that legitimates his belief-system qua sociological fact.

f. The Projection Theory of Religion

This raises the intellectual plausibility of the projection theory of religion. The theory arose as a response to the anthropomorphic nature of the attributes which the conceptualization of a personal God seems to necessitate. Freud, like Feuerbach, took this as entailing strict anthropotheistic consequences.

However, such a view underestimates the logical gulf that exists between wishes and beliefs. Even if there is a universal wish for a Cosmic father, it is implausible to suggest that such a wish is a sufficient condition for religious belief. Concerns about anthropomorphisms in religious language are not restricted to religious skeptics.

It is thus perfectly consistent to accept projectionism as an account of religious concept formation without thereby repudiating religious belief. The logical compatibility has led some religious thinkers to embrace projectionism. The view that religious representations are products of the human imagination can be accepted implicitly by believers.

Whatever level of plausibility may be assigned to these views, it is clear that the projection theory is reflective of the difficulties which certain forms of religious discourse generate. The characterization of God as possessing attributes seems to invite the challenge found in Freud. The projection theory highlights theological and philosophical issues.

g. Moses and Monotheism: Interpretive Approaches

Moses and Monotheism is the most controversial of Freud’s works, seeking to utilize psychoanalytic theory to reinterpret historical events. The Freudian narrative is problematic when considered as a putative exegesis. Freud’s willingness to construct such a speculative narrative has puzzled scholars.

For much of his life, Freud presented an image of himself as a cosmopolitan intellectual, committed to secular humanism. Some scholars have represented the Moses text primarily as a critique of Judaism. Others repudiate what they see as a confusion of meaning with motivation, stressing what Freud sought to convey. This approach rejects any autobiographical interpretation.

Finally, there is the semi-autobiographical approach, which sees the text as primarily concerned with resolving his personal father complex. At that point in Jewish history, Freud was seeking to affirm his cultural indebtedness to the ethical basis of the religion of his forefathers.

9. References and Further Reading

a. References

- Alter, R. 1988. The Invention of Hebrew Prose, Modem Fiction and the Language of Realism (Samuel and Athea Stroum Lectures in Jewish Studies). University of Washington Press.

- Assmann, J. 1998. Moses the Egyptian: The Memory in Western Monotheism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Banks, R. 1973. ‘Religion as Projection: A Re-Appraisal of Freud’s Theory’. Religious Studies, vol. 9 (4), 401-426.

- Berke, J. 2015. The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots. London: Karnac Books.

- Bernstein, R.J. 1998. Freud and the Legacy of Moses. Cambridge: University Press.

- Boehlich, W. (ed.) 1992. The Letters of Sigmund Freud to Eduard Silberstein, 1871-1881 (trans. A. Pomerans). Harvard University Press.

- Brentano, F. 1973 (orig. 1874). Psychology From an Empirical Standpoint (trans. A.C. Rancurello, D.B. Terrell and L.L. McAlister). London: Routledge.

- d’Aquili, E.G. & Newberg, A.B. 1999. The Mystical Mind: Probing the Biology of Religious Experience. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

- Darwin, C. 1981. Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. Princeton University Press.

- Durkheim, É. 1995 (orig. 1912). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (trans. Karen Fields). New York: Free Press.

- Feuerbach, L. 1881. The Essence of Christianity, 2nd edition (trans. George Eliot). London: Trübner & Co., Ludgate Hill.

- Frazer, J. G. 2002 (orig. 1890). The Golden Bough. New York: Dover Publications.

- Freud, S. 1914 (orig. 1901). The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (trans. A.A. Brill). London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Freud, S. 1939. Moses and Monotheism (trans. Katherine Jones). London: The Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Freud, S. 1957 (orig. 1910) ‘The Future Prospects of Psychoanalytic Therapy’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud ( & and ed. J. Strachey) Volume X1 (1911-1913). W. W. Norton & Company, 139-151.

- Freud, S. 1959. ‘An Autobiographical Study’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (trans. & ed. J. Strachey). Volume XX (1925-1926). London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 7-70.

- Freud, S. 1961 (orig. 1927). The Future of an Illusion (trans. James Strachey). New York; W.W. Norton.

- Freud, S. 1962 (orig. 1930). Civilization and its Discontents (trans. James Strachey). New York; W.W. Norton.

- Freud, S. 1976. ‘An Obituary for Professor S. Hammerschlag’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (trans. & and ed. J. Strachey) Volume IX (1906-1908). W. W. Norton & Company, 255-6.

- Freud, S. 1976 (orig. 1907). ‘Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (trans. & ed. James Strachey) Volume IX (1906-1908). W. W. Norton & Company, 115-128.

- Freud, S. 1986. The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887-1904 (trans. & ed. J. Moussaieff Masson). The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Freud, S. 1990 (orig. 1933). New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis (trans. James Strachey). New York: W.W. Norton.

- Freud, S. 2001 (orig. 1913). Totem and Taboo: Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics (trans. James Strachey). Oxford: Routledge Classics.

- Freud, S. 2010 (orig. 1900, 1908) The Interpretation of Dreams (trans. James Strachey). New York: Basic Books.

- Friedman, R. 1998. ‘Freud’s Religion: Oedipus and Moses’. Religious Studies, 34 (2), 135-149.

- Gay, Peter. 1987. A Godless Jew? Freud, Atheism and the Making of Psychoanalysis. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Goodnick, B. 1992. ‘Jacob Freud’s Dedication to His Son: A Reevaluation’. The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 82 (3-4), 329-360.

- Green, G. 2000. Theology, Hermeneutics and Imagination: The Crisis of Interpretation at the End of Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gresser, M. 1994. Dual Allegiance: Freud as a Modern Jew. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Grünbaum, A. The Foundations of Psychoanalysis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hume, D. 1956 (orig. 1757). The Natural History of Religion (ed. H.E. Root). London: A.C. Black.

- Jones, E. 1957. Sigmund Freud. Life And Work: Volume Three – The Last Phase 1919-1939. London: Hogarth Press.

- Jones, E. 1959 (ed). Freud: Collected Papers in 5 Volumes (trans. Joan Riviere). New York: Basic Books.

- Kai-man Kwan. 2006 “Are Religious Beliefs Human Projections?” in Raymond Pelly and Peter Stuart, eds., A Religious Atheist? Critical Essays on the Work of Lloyd Geering. Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press, 41-66.

- Kenny, R. 2015. ‘Freud, Jung and Boas: the psychoanalytic engagement with anthropology revisited’. Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Jun 20; 69(2): 173–190. Online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4424604/

- Kroeber, A.L. 1920. ‘Totem and Taboo: An Ethnologic Psychoanalysis’, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 22 (1), 48-55.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1939. ‘Totem and Taboo in Retrospect’. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 45 (3), 446-451

- Lang, A. & Atkinson, J.J. 1903. Social Origins and Primal Law. London: Longmans Green.

- Parsons, W.B. 1998. “The Oceanic Feeling Revisited.” The Journal of Religion, vol. 78 (4), 501–523.

- Paul, R. A. 1996. Moses and Civilization: The Meaning Behind Freud’s Myth. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

- Plantinga, A. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. Oxford University Press.

- Popper, K. 1963. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Rice, E. 1990. Freud and Moses: The Long Journey Home. Albany, New York: SUNY Press.

- Ricoeur, P. 1970. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation (trans. D. Savage). New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- Saarinen, J.A. 2015. A Conceptual Analysis of the Oceanic Feeling – With a Special Note on Painterly Aesthetics. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Printing House. Online at: https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/bitstream/handle/123456789/45384/978-951-39-6078-0_vaitos07032015.pdf?sequence=1

- Schmidt, W. 1912-1955. Der Ursprung der Gottesidee: Eine historisch-kritische und positive Studie. (12 vols.) Münster in Westfalen: Aschendorff.

- Slavet, E. 2009. Racial Fever: Freud and the Jewish Question. Fordham University Press.

- Slavet, E. 2010. ‘Freud’s Theory of Jewishness For Better and for Worse’. In A.D. Richards (ed.) The Jewish World of Sigmund Freud: Essays on Cultural Roots and the Problem of Religious Identity, 96-111. North Carolina: McFarland & Co.

- Smith, R.J. 2016. ‘Darwin, Freud, and the Continuing Misrepresentation of the Primal Horde’, Current Anthropology 57 (6), 838-843.

- Thornton, S. ‘Projection’, In R.A. Segal and K. von Stuckrad (eds.) Vocabulary for the Study of Religion (vol. 3). Leiden/Boston, 2015, 138-144.

- Tylor, E.B. 1871. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art, and custom (2 vols). London: John Murray.

- Tylor, E.B. 1881. Anthropology: an introduction to the study of man and civilization. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Whitebook, J. 2017. Freud: An Intellectual Autobiography. Cambridge University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1966. Lectures & Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief (ed. C. Barrett). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1974. Philosophical Investigations (trans. G.E.M. Anscombe). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Yerushalmi, Y.H. 1993. Freud’s “Moses”: Judaism Terminable and Interminable. Yale University Press.

b. Further Reading

- Alston, W.P. 2003. ‘Psychoanalytic theory and theistic belief’. In C. Taliafero, & P. Griffiths (eds.). Philosophy of Religion: An anthology (123-140). Oxford: Blackwell Press.

- Bingaman, K. 2012. Freud and Faith: Living in the Tension. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Blass, R.B. 2004. ‘Beyond illusion: Psychoanalysis and Religious Truth’. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85, 615-634.

- Derrida, J. 1998. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (trans. E. Prenowitz). University of Chicago Press.

- Gay, P. 2006. Freud: A Life for our Time. London: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Ginsburg, R. et.al. (eds). 2006. New Perspectives on Freud’s Moses and Monotheism (Conditio Judaica) 1st Edition. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

- Hewitt, M.A. 2014. Freud on Religion. London & New York: Routledge.

- R.A. 1986. Emile Durkheim: An Introduction to Four Major Works. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Kolbrener, W. (2010). ‘Death of Moses Revisited: Repetition and Creative Memory in Freud and the Rabbis’. American Imago, 67 (2), 243-262.

- Milfull, J. 2002. ‘Freud, Moses and the Jewish Identity’. The European Legacy, vol. 7, 25-31.

- Nobus, D. 2006. ‘Sigmund Freud and the Case of Moses Man: On the Knowledge of Trauma and the Trauma of Knowledge’. JEP: European Journal of

- Psychoanalysis: Humanities, Philosophy, Psychotherapies. Number 22 (1). Online at http://www.psychomedia.it/jep/number22/nobus.htm

- Ofengenden, A. 2015. ‘Monotheism, the Incomplete Revolution: Narrating the Event in Freud’s and Assmann’s Moses’. Symploke, Volume 23 (1-2), 291-307.

- Palmer, M. 1997. Freud and Jung on Religion. London & New York: Routledge.

- Said, E. 2004. Freud and the Non-European. London: Verso.

- Smith, D.L. 1999. Freud’s Philosophy of the Unconscious. Studies in Cognitive Systems, vol. 23. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Tauber, A.I. 2010. Freud, The Reluctant Philosopher. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Author Information

Stephen Thornton Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick Ireland

FAQ About Freud’s Views on Religion

1. What was Freud’s main theory about the origin of religion?

Freud believed that religion originated from the father complex, where God is seen as an exalted father figure providing protection and authority.

2. Did Freud consider religion to be beneficial or harmful?

Freud viewed religion as both beneficial and harmful. He acknowledged its role in providing comfort and structure but also saw it as a form of mass delusion.

3. How did Freud’s personal background influence his views on religion?

Freud’s Jewish heritage and complex relationship with his father heavily influenced his views, leading him to explore the psychological roots of religious belief.

4. What is the Oedipus complex, and how does it relate to Freud’s view of religion?

The Oedipus complex involves a child’s unconscious sexual desire for the parent of the opposite sex and rivalry with the parent of the same sex. Freud believed that religion mirrored this complex, with God representing the powerful father figure.

5. How did Freud’s contemporaries react to his theories on religion?

Freud’s theories were met with mixed reactions, ranging from enthusiastic support to strong criticism from both religious and scientific communities.

6. What is projectionism, and how did Freud apply it to religion?

Projectionism is the theory that religious beliefs are projections of human needs and desires onto a divine figure. Freud used this concept to explain how people create God in their own image.

7. How did Freud’s views on totemism influence his understanding of religion?

Freud saw totemism as a primitive form of religion where a group identifies with a totem animal, which he linked to the primal father figure.

8. What role does guilt play in Freud’s account of the origins of religion?

Freud believed that guilt, particularly from the primal act of parricide, drives the need for religious rituals and beliefs aimed at atonement and reconciliation.

9. How did Freud reconcile his views on religion with his own Jewish identity?

In his later work, particularly Moses and Monotheism, Freud attempted to reconcile his critique of religion with an affirmation of Jewish ethical values.

10. What are some modern criticisms of Freud’s theories on religion?

Modern criticisms include the lack of empirical evidence, the reliance on outdated anthropological theories, and the unfalsifiable nature of psychoanalytic concepts.

Are you struggling to compare different perspectives on complex topics like Freud’s theories on religion? Visit COMPARE.EDU.VN for detailed analyses and comparisons that help you make informed decisions. Our comprehensive resources provide objective insights to simplify your research and understanding. For more information, contact us at:

Address: 333 Comparison Plaza, Choice City, CA 90210, United States

WhatsApp: +1 (626) 555-9090

Website: compare.edu.vn