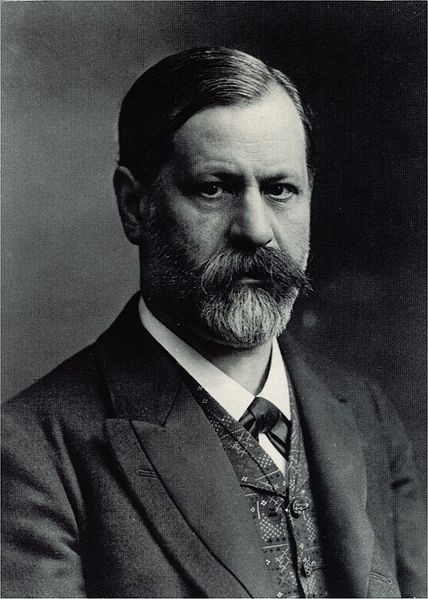

Did Freud Compare Religion To A Sporting Event, exploring the psychological origins of religious belief? At compare.edu.vn, we delve into Sigmund Freud’s perspectives, offering insights into his psychoanalytic interpretation of religion as a shared illusion rooted in human desires. Discover how religious practices are paralleled with neuroses and understand the nuances.

1. Psychoanalysis and Religion: A Freudian Perspective

Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis fundamentally rests on the theory of infantile sexuality, which posits that an individual’s psychological development progresses through several stages where libidinal drives are directed toward specific pleasure-release zones. These stages span from the oral to the anal, phallic, and eventually, the genital stage in maturity. Freud viewed psychosexual development as a series of conflicts resolved by internalizing control mechanisms, primarily derived from authoritative figures like parents through the superego.

During infancy, this progression involves parental control introducing behavioral prohibitions and limitations, necessitating the repression, displacement, or sublimation of libidinal drives. Neuroses, including psychosomatic symptoms, arise either from external trauma or the failure to resolve internal conflicts between libidinal urges and psychological control mechanisms. These often manifest as compulsive behaviors, such as repetitive ceremonial movements or obsessions with hygiene, which impede normal life and require psychotherapeutic intervention.

1.1 The Oedipus Complex and the Father Complex

Central to Freud’s theory is the resolution of the Oedipus complex, occurring during the phallic stage, where a male child develops a sexual attachment to the mother and views the father as a sexual rival. Resolution involves repressing the drive toward the mother and identifying with the father, crucial for forming sexuality. Freud termed the associations relating to the son-father relationship “the father complex,” viewing it as essential for understanding human developmental psychology and social phenomena, including religious belief and practice.

1.2 Freud’s Hermeneutic of Suspicion

In his analysis of religion, Freud employed a hermeneutic of suspicion, a reductive interpretation style that challenged conventional meanings in favor of deeper psychological truths. This approach sought to reveal the true origins and significance of religion in human life, using psychotherapy techniques to achieve this. Freud’s stance aligns with the naturalistic tradition, asserting that the concept of God is an anthropomorphic construct rooted in the father complex within social groups.

1.3 The God of Each Individual

“The psycho-analysis of individual human beings,” he stated in Totem and Taboo, “teaches us with quite special insistence that the god of each of them is formed in the likeness of his father, that his personal relation to God depends on his relation to his father in the flesh and oscillates and changes along with that relation, and that at bottom God is nothing other than an exalted father.”

This article will explore the considerations leading to this view, its articulation in Freud’s writings on religion, and the critical responses it has elicited.

2. Freud’s Jewish Heritage: Influences and Conflicts

Born to Jewish parents in Freiberg, Freud’s upbringing profoundly influenced his perspectives on religion. His father, Jacob, a businessman with rabbinical lineage, ensured Sigmund received a traditional Jewish education, including Biblical studies in Hebrew. Freud developed admiration for Rabbi Samuel Hammerschlag, a proponent of humanistic Reform Judaism, who instilled in him a lasting commitment to Enlightenment values.

2.1 Estrangement and Reconciliation

Despite these positive influences, Freud grew increasingly hostile to orthodox Jewish belief from adolescence onward, likely causing estrangement from his father. Jacob’s attempt at reconciliation on Sigmund’s 35th birthday, presenting him with a newly rebound family Bible accompanied by a lyrical dedication referencing their shared heritage, initially appeared unsuccessful. Freud never mentioned the dedication, yet after his death, the Bible was found perfectly preserved.

2.2 The Impact of Jacob’s Death

The death of Jacob in 1896 precipitated a period of reflection, leading Freud to recognize his past hostility toward his father stemmed from seeing Jacob as a rival for his mother’s love. This realization led to the development of the Oedipus complex. Freud later acknowledged that his articulation of psychoanalysis was a result of resolving the crisis generated by Jacob’s death.

2.3 Affirming Jewish Heritage

Still, the conflict generated by the demand to find a means of affirming the richness and particularity of his Jewish cultural heritage without acceding to the Biblical and theological orthodoxies associated with it, remained unresolved. This problem is one of the keys to an understanding of his final work, Moses and Monotheism.

3. Philosophical Connections: Brentano and Lipps

Freud’s intellectual development was significantly shaped by philosophers Franz Brentano and Theodor Lipps. Brentano, author of Psychology From an Empirical Standpoint, emphasized empirical methods in psychology and the importance of logical rigor and scientific findings in philosophy. Freud admired Brentano’s lectures but diverged on key issues such as rational theism and the notion of unconscious mental states.

3.1 Brentano’s Influence

Brentano revitalized the principle of intentionality, defining mental phenomena as necessarily directed towards intentional objects. He argued for the epistemic certainty and transparency of mental phenomena accessible through inner perception, contrasting with the uncertainty in perceiving physical phenomena.

3.2 The Unconscious Mind

Brentano considered that one of the key problems for an empirical psychology was that of constructing an adequate picture of the internal dynamics of the mind from an analysis of the complex interplay between diverse mental phenomena, on the one hand, and the interactions between the mind and the external world, on the other. But he set his face implacably against admitting the notion of unconscious mental states and processes into a fully scientific psychology.

3.3 Theodor Lipps and Aesthetic Empathy

Theodor Lipps supported Freud’s conviction, positing that scientific psychology necessitated reference to the unconscious. Lipps extended the notion of aesthetic empathy into the psychological realm, designating the process that allows us to comprehend and respond to the mental lives of others by putting ourselves in their place.

3.4 Psychological Projection

Freud integrated Lipps’ account of projection centrally in his psychoanalytic theory, regarding it as a precondition for establishing the relationship between patient and analyst which alone makes the interpretation of unconscious processes possible. Concomitant to the idea of psychological projection is the notion that the human need to ascribe psychological states to others can and does readily lead to situations in which such ascriptions are extended beyond their legitimate boundaries in the human realm.

3.5 Ludwig Feuerbach and God

In his Essence of Christianity, Ludwig Feuerbach critiqued religion, arguing that the idea of God is an anthropomorphic construct embodying idealized human nature. Freud accepted this view, integrating it into psychoanalysis to explain why religious anthropomorphisms arise. Freud accordingly integrated his account of religion into the broader project of psychoanalysis, suggesting that “a large portion of the mythological conception of the world which reaches far into the most modern religions is nothing but psychology projected into the outer world… We venture to explain in this way the myths of paradise and the fall of man, of God, of good and evil, of immortality and the like—that is, to transform metaphysics into meta-psychology”.

4. The Orientation of Freud’s Approach to Religion

In articulating this project, Freud drew deeply upon a wide variety of anthropological sources, particularly the work of such contemporary luminaries as John Ferguson McLennan (1827—1881), Edward Burnett Tylor (1832—1917), John Lubbock (1834—1913), Andrew Lang (1844—1912), James George Frazer (1854—1941) and Robert Ranulph Marett (1866—1943) on the connection between social structures and primitive religions. Freud’s claim to originality in this context resides in his attempt to situate projectionism within the framework of psychoanalysis, ultimately interpreting the social origins and cultural significance of the religious impulse in terms paralleling his account of the father-son relationship in individual psychology.

4.1 The Evolutionist Paradigm

The evolutionist paradigm, which projected a universal linear cultural development from the primitive to the civilized, with the differences found in human societies reflecting stages in that development, gradually came to function as a background assumption in Freud’s thought from an early stage. Tylor held that, in terms of human interaction with the world at large, civilization progresses through three developmental “stages,” from magic through religion to science, with contemporary Western culture representative of the final stage. This view was rearticulated by Frazer in his famous Golden Bough and referenced approvingly by Freud, though he emphasized that elements of the first two stages continue to operate in contemporary life.

4.2 Religion as a Childlike Condition

Furthermore, Freud found in Tylor’s and Frazer’s evolutionist account of cultural progress an implication which had been affirmed explicitly by Feuerbach: “Religion is the childlike condition of humanity;” it belongs to a social developmental stage paralleling that of the individual, through which each civilization must pass en route to the maturity of scientific understanding. It was perhaps this latter, more than any other factor, which was to suggest to Freud that the psychoanalytical techniques which he pioneered in his account of individual psychology could be applied socially, to explain the nature of the religious impulse in human life generally.

5. Totemism and the Father Complex: Origins of Religion

Some of Freud’s earliest comments on religion give immediate evidence of the psychologically reductionist direction which his thought was to take, which represented the dynamic underpinning religion as deriving from the powerfully ambivalent relationship between the child and his apparently omnipotent father. For example, in his 1907 paper “Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices” he drew attention to similarities between neurotic behavior and religious rituals, suggesting that the formation of a religion has, as its “pathological counterpart,” obsessional neurosis, such that it might be appropriate to describe neurosis “as an individual religiosity and religion as a universal obsessional neurosis,” a view which he was to retain for the remainder of his life.

5.1 Totem and Taboo

Freud’s first sustained treatment of religion in these terms occurs in his 1913 Totem and Taboo, in the context of his account, heavily influenced in particular by the work of James George Frazer, Andrew Lang and J.J. Atkinson, of the relationship between totemism and the incest prohibition in primitive social groupings. The prominence and strength of the incest taboo was of considerable interest to him as a psychologist, not least because he saw it as one of the keys to an understanding of human culture and as deeply linked to the concepts of infantile sexuality, Oedipal desire, repression and sublimation which play such a key role in psychoanalytic theory. In tribal groups the incest taboo was usually associated with the totem animal with which the group identified and after which it was named.

5.2 Origins of Human Morality

Such prohibitions, Freud believed, are extremely important as they constitute the origins of human morality, and he offered a reconstruction of the genesis of totem religions in human culture in terms which are at once forensically psychoanalytical and rather egregiously speculative. The primal social state of our pre-human ancestors, he argued, closely following J.J. Atkinson’s account in his Primal Law, was that of a patriarchal “horde” in which a single male jealously maintained sexual hegemony over all of the females in the group, prohibiting his sons and other male rivals from engaging in sexual congress with them.

5.3 The Primal Parricide

The parricidal deed, Freud asserted, is the single “great event with which culture began and which, since it occurred, has not let mankind a moment’s rest”, the acquired memory traces of which underpins the whole of human culture, including, and in particular, both totem and developed religions. The counterpart to the primary taboo against killing or eating the totem animal, Freud pointed out, is the annual totem feast, in which that very prohibition is solemnly and ritualistically violated by the tribal community, and he followed the Orientalist William Robertson Smith (1846—1894) in linking such totem feasts with the rituals of sacrifice in developed religions.

5.4 Ambivalence in Religion

Freud saw no contradiction in such a ritual, holding that the ambivalence contained in the father-complex pervades both totemic and developed religions: “Totemic religion not only comprises expressions of remorse and attempts at atonement, it also serves as a remembrance of the triumph over the father”. The father is thus represented twice in primitive sacrifice, as god and as totem animal, the totem being the first form taken by the father substitute and the god a later one in which the father reassumes his human identity.

6. Religion and Civilization: Substitutions and Illusions

In time Freud came to consider that the account which he had given in Totem and Taboo did not fully address the issue of the origins of developed religion, the human needs which religion is designed to meet and, consequently, the psychological motivations underpinning religious belief. He turned to these questions in his The Future of an Illusion and Civilization and its Discontents. In the two works he represented the structures of civilization, which permit men to live in mutually beneficial communal relationships, as emerging only as a consequence of the imposition of restrictive processes on individual human instinct.

6.1 The Role of Religion

Extending his account of repression from individual to group psychology, Freud contended that, with the refinement of culture, the external coercive measures inhibiting the instincts become largely internalized. Professional work, Freud argued, is one area in which such substitutions take place, while the aesthetic appreciation of art is another significant one; for art, though it is inaccessible to all but a privileged few, serves to reconcile human beings to the individual sacrifices that have been made for the sake of civilization. For that effect, in particular for the achievement of consolation for the suffering and tribulations of life, religious ideas become invoked; these ideas, he held, consequentially become of the greatest importance to a culture in terms of the range of substitute satisfactions which they provide.

6.2 Religion as Grandiose

The role which religion has played in human culture was thus described by Freud in his 1932 lecture “On the Question of a Weltanschauung” as nothing less than grandiose; because it purports to offer information about the origins of the universe and assures human beings of divine protection and of the achievement of ultimate personal happiness, religion “is an immense power, which has the strongest emotions of human beings at its service”. Since religious ideas thus address the most fundamental problems of existence, they are regarded as the most precious assets civilization has to offer, and the religious worldview, which Freud acknowledged as possessing incomparable consistency and coherence, makes the claim that it alone can answer the question of the meaning of life.

6.3 The Father-Son Relationship

For Freud, then, the cultural and social importance of religion resides both in reconciling men to the limitations which membership of the community places upon them and in mitigating their sense of powerlessness in the face of a recalcitrant and ever-threatening nature. It is in this sense, he argued, that the father-son relationship so crucial to psychoanalysis demands the projection of a deity configured as an all-powerful, benevolent father figure.

6.4 Religious Ideas as Illusions

Genetically, Freud argued, religious ideas thus owe their origin neither to reason nor experience but to an atavistic need to overcome the fear of an ever-threatening nature: “[they] are not precipitates of experience or end results of thinking: they are illusions, fulfilments of the oldest, strongest and most urgent wishes of mankind. The secret of their strength lies in the strength of those wishes”. In declaring such ideas illusory Freud did not initially seek to suggest or imply that they are thereby necessarily false.

6.5 Religious Beliefs as Delusional

By the time he wrote Civilization and its Discontents he was prepared to take his religious skepticism a stage further, explicitly declaring religious beliefs to be delusional, not only on an individual but on a mass scale: “A special importance attaches to the case in which [the] attempt to procure a certainty of happiness and a protection against suffering through a delusional remolding of reality is made by a considerable number of people in common. The religions of mankind must be classed among the mass-delusions of this kind”.

6.6 The Turning Away from Religion

Given that religion has, as Freud acknowledged, made very significant contributions to the development of civilization, and that religious beliefs are not strictly refutable, the question arises as to why he came to consider that religious beliefs are delusional and that a turning away from religion is both desirable and inevitable in advanced social groupings. The answer given in Civilization and its Discontents is that, in the final analysis, religion has failed to deliver on its promise of human happiness and fulfillment.

6.7 Education to Reality

That Freud saw the movement from religious to scientific modes of understanding as a positive cultural development cannot be doubted; indeed, it is one which he saw himself facilitating in a process analogous to the therapeutic resolution of individual neuroses: “Men cannot remain children for ever; they must in the end go out into ‘hostile life’. We may call this education to reality. Need I confess to you that the sole purpose of my book is to point out the necessity for this forward step?”

7. The Moses Narrative: The Origins of Judaic Monotheism

In 1939, while exiled in Britain and suffering from the throat cancer which was to lead to his death, Freud published his final and most controversial work, Moses and Monotheism. Written over a period of many years and sub-divided into discrete segments, two of which were published independently in the periodical Imago in 1937, the book has an inelegant structure.

7.1 Moses and Egypt

The focal point of the work is the figure of Moses and his connection with Egypt, which had exerted a fascination on Freud since his childhood study of the Philippson bible, as evidenced also in his publication of the essay “The Moses of Michelangelo” in 1914. Accordingly, at this late juncture in his life and with the threat of fascist antisemitism looming over Europe, he turned his attention once more to the religion of his forefathers, constructing an alternative narrative to the orthodox Biblical one on the origins of Judaism and the emergence from it of Christianity.

7.2 Akhenaten’s Revolution

Developing a thesis partly suggested by work of the protestant theologian Ernst Sellin in 1922, Freud argued that the historical Moses was not born Jewish but was rather an aristocratic Egyptian who functioned as a senior official or priest to the Pharaoh Amenhotep IV. The latter had introduced revolutionary changes to almost all aspects of Egyptian culture in the 14th century B.C.E., changing his name to Akhenaten, centralizing governmental administration and moving the capital from Thebes to the new city of Akhetaten.

7.3 Exodus and Yahweh

In the Freudian narrative the onerous demands of the new religion ultimately led his followers to rebel and to kill Moses, an effective repetition of the original father murder outlined in Totem and Taboo, after which they turned to the cult of the volcano god Yahweh. By this means the guilt deriving from the murder of the original Moses survived in the collective unconscious of the Jewish people and led to the hope of a messiah who would redeem them for their forefathers’ murderous act.

7.4 Ethical Traditions within Judaism

While Freud evidently retained his view of religion as the analogue of an obsessional neurosis, this account now contained the recognition that, as such, its effects are not necessarily pathological, but, on the contrary, can also be socially and culturally beneficial in a marked way. Thus he points out in his narrative that, through the example and guidance of the great prophets, there arose an ethical tradition within Judaism, ultimately traceable back to Moses the Egyptian, which proscribed iconic representation and ceremonial performance, demanding in their place belief and “a life of truth and justice”, a tradition with which Freud evidently had deep affinity.

7.5 Essential Features of Monotheism

This narrative account of the rootedness of the Jewish monotheistic tradition in the life and murder of the man Moses captures what Freud believed to be its most essential feature, something “majestic,” an eternal truth, “historic” rather than “material,” that “in primaeval times there was one person who must needs appear gigantic and who, raised to the status of a deity, returned to the memory of men”.

8. Critical Responses: Diverse Perspectives on Freud’s Theories

Freud’s utilization of the conceptual apparatus of psychoanalysis in his treatment of religion yields a naturalistic account rooted in psychoanalytic theory which, while being arguably one of the more self-consistent to be found in the modern age, is also one of the most controversial. In its main features it strongly anticipated, and almost certainly influenced, contemporary critiques of religion associated with the “New Atheism” movement of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, such as those of Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens. The responses to it, in turn, occupy a very wide spectrum, from enthusiastic affirmation to condemnatory repudiation.

8.1 The Anthropological Critique

The idea of the “primal horde” was derived by Atkinson and Freud from what was no more than a cautious suggestion by Darwin in his Descent of Man that, amongst several possibilities regarding the social organization of “primeval” humans, one was that it might have consisted of small patriarchal groups led by a single dominant male, “each with as many wives as he could support and obtain, whom he would have jealously guarded against all other men”. This suggestion, which became one of the linchpins of Freud’s account of totem religion, has not received scientific corroboration, and it remains questionable whether the idea has any basis in reality.

8.2 Myth or Science? Examining Psychoanalysis

For these reasons, Freud’s projectionist theory of religion as evolving from a primal parricide has been called into serious question as a scientific or historical hypothesis, and with it, the status of psychoanalysis itself. Karl Popper and Ludwig Wittgenstein have both argued against Freud’s repeated claim for the scientific status of psychoanalysis and—by implication—the account of religion which he developed from it.

8.3 Lamarckian vs. Darwinian Evolutionary Principles

As we have seen, Freud’s transposition of the father complex from individual infantile development to the social order relied heavily on Haeckel’s thesis that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. The latter is now largely rejected by contemporary science, in particular the manner in which Freudians have adopted it to model the social evolution of human beings analogically with the psychological development of children.

8.4 The Primordial Religion: Polytheism or Monotheism?

The entire enterprise of accounting for the origins of religion as an evolutionary trajectory from polytheism to monotheism has been challenged by the work of the ethnologist Father Wilhelm Schmidt, whose multi-volume Der Ursprung der Gottesidee is a wide-ranging study of primitive religion. In it Schmidt argued that the “original” tribal religion was almost invariably a form of primitive monotheism, focused on belief in a single benevolent creator god, with polytheistic religions featuring at a later stage of cultural development.

8.5 Religion as a Social Phenomenon

It is instructive to compare Freud’s attempts to deal with the social dimension of religion with that of his near contemporary, the sociologist Émile Durkheim, whose study The Elementary Forms of Religious Life has been highly influential, though it should not in any way be seen as a response to Freud. For Durkheim, the social dimension of human life is primary; human individuality itself is largely determined by, and is a function of, social interaction and organization.

8.6 The Projection Theory of Religion

This raises the whole question of the intellectual plausibility of the projection theory of religion. The question is a complex one, a fact which Freud scarcely acknowledges in his works. As we have seen, the theory, which has a number of related but distinct forms, arose in modernity as a response to the anthropomorphic nature of the attributes which the conceptualization of a personal God in many of the great world religions seems to necessitate.

8.7 Moses and Monotheism: Interpretive Approaches

Moses and Monotheism is the most controversial of Freud’s works, seeking as it does to both utilize psychoanalytic theory to reinterpret key historical events and to embed psychoanalysis within a historiographical narrative. Not alone did it contest the orthodox Biblical narrative of the role of Moses in the history of Judaism, it did so at a time when the Jews of Europe were threatened with complete annihilation. It is unsurprising, then, that it should have become the subject of very strong criticism, on the grounds both of methodology and content.

9. References and Further Reading

Below are references and recommended readings that offer deeper insights into Sigmund Freud’s theories on religion and related topics.

9.1 References

- Alter, R. 1988. The Invention of Hebrew Prose, Modem Fiction and the Language of Realism (Samuel and Athea Stroum Lectures in Jewish Studies). University of Washington Press.

- Assmann, J. 1998. Moses the Egyptian: The Memory in Western Monotheism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Banks, R. 1973. ‘Religion as Projection: A Re-Appraisal of Freud’s Theory’. Religious Studies, vol. 9 (4), 401-426.

- Berke, J. 2015. The Hidden Freud: His Hassidic Roots. London: Karnac Books.

- Bernstein, R.J. 1998. Freud and the Legacy of Moses. Cambridge: University Press.

- Boehlich, W. (ed.) 1992. The Letters of Sigmund Freud to Eduard Silberstein, 1871-1881 (trans. A. Pomerans). Harvard University Press.

- Brentano, F. 1973 (orig. 1874). Psychology From an Empirical Standpoint (trans. A.C. Rancurello, D.B. Terrell and L.L. McAlister). London: Routledge.

- d’Aquili, E.G. & Newberg, A.B. 1999. The Mystical Mind: Probing the Biology of Religious Experience. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

- Darwin, C. 1981. Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. Princeton University Press.

- Durkheim, É. 1995 (orig. 1912). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (trans. Karen Fields). New York: Free Press.

- Feuerbach, L. 1881. The Essence of Christianity, 2nd edition (trans. George Eliot). London: Trübner & Co., Ludgate Hill.

- Frazer, J. G. 2002 (orig. 1890). The Golden Bough. New York: Dover Publications.

- Freud, S. 1914 (orig. 1901). The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (trans. A.A. Brill). London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Freud, S. 1939. Moses and Monotheism (trans. Katherine Jones). London: The Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Freud, S. 1957 (orig. 1910) ‘The Future Prospects of Psychoanalytic Therapy’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud ( & and ed. J. Strachey) Volume X1 (1911-1913). W. W. Norton & Company, 139-151.

- Freud, S. 1959. ‘An Autobiographical Study’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (trans. & ed. J. Strachey). Volume XX (1925-1926). London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 7-70.

- Freud, S. 1961 (orig. 1927). The Future of an Illusion (trans. James Strachey). New York; W.W. Norton.

- Freud, S. 1962 (orig. 1930). Civilization and its Discontents (trans. James Strachey). New York; W.W. Norton.

- Freud, S. 1976. ‘An Obituary for Professor S. Hammerschlag’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (trans. & and ed. J. Strachey) Volume IX (1906-1908). W. W. Norton & Company, 255-6.

- Freud, S. 1976 (orig. 1907). ‘Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices’, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (trans. & ed. James Strachey) Volume IX (1906-1908). W. W. Norton & Company, 115-128.

- Freud, S. 1986. The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887-1904 (trans. & and ed. J. Moussaieff Masson). The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Freud, S. 1990 (orig. 1933). New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-analysis (trans. James Strachey). New York: W.W. Norton.

- Freud, S. 2001 (orig. 1913). Totem and Taboo: Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics (trans. James Strachey). Oxford: Routledge Classics.

- Freud, S. 2010 (orig. 1900, 1908) The Interpretation of Dreams (trans. James Strachey). New York: Basic Books.

- Friedman, R. 1998. ‘Freud’s Religion: Oedipus and Moses’. Religious Studies, 34 (2), 135-149.

- Gay, Peter. 1987. A Godless Jew? Freud, Atheism and the Making of Psychoanalysis. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Goodnick, B. 1992. ‘Jacob Freud’s Dedication to His Son: A Reevaluation’. The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 82 (3-4), 329-360.

- Green, G. 2000. Theology, Hermeneutics and Imagination: The Crisis of Interpretation at the End of Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gresser, M. 1994. Dual Allegiance: Freud as a Modern Jew. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Grünbaum, A. The Foundations of Psychoanalysis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hume, D. 1956 (orig. 1757). The Natural History of Religion (ed. H.E. Root). London: A.C. Black.

- Jones, E. 1957. Sigmund Freud. Life And Work: Volume Three – The Last Phase 1919-1939. London: Hogarth Press.

- Jones, E. 1959 (ed). Freud: Collected Papers in 5 Volumes (trans. Joan Riviere). New York: Basic Books.

- Kai-man Kwan. 2006 “Are Religious Beliefs Human Projections?” in Raymond Pelly and Peter Stuart, eds., A Religious Atheist? Critical Essays on the Work of Lloyd Geering. Dunedin, New Zealand: Otago University Press, 41-66.

- Kenny, R. 2015. ‘Freud, Jung and Boas: the psychoanalytic engagement with anthropology revisited’. Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. Jun 20; 69(2): 173–190. Online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4424604/

- Kroeber, A.L. 1920. ‘Totem and Taboo: An Ethnologic Psychoanalysis’, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 22 (1), 48-55.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1939. ‘Totem and Taboo in Retrospect’. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 45 (3), 446-451

- Lang, A. & Atkinson, J.J. 1903. Social Origins and Primal Law. London: Longmans Green.

- Parsons, W.B. 1998. “The Oceanic Feeling Revisited.” The Journal of Religion, vol. 78 (4), 501–523.

- Paul, R. A. 1996. Moses and Civilization: The Meaning Behind Freud’s Myth. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

- Plantinga, A. 2000. Warranted Christian Belief. Oxford University Press.

- Popper, K. 1963. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Rice, E. 1990. Freud and Moses: The Long Journey Home. Albany, New York: SUNY Press.

- Ricoeur, P. 1970. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation (trans. D. Savage). New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- Saarinen, J.A. 2015. A Conceptual Analysis of the Oceanic Feeling – With a Special Note on Painterly Aesthetics. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Printing House. Online at: https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/bitstream/handle/123456789/45384/978-951-39-6078-0_vaitos07032015.pdf?sequence=1

- Schmidt, W. 1912-1955. Der Ursprung der Gottesidee: Eine historisch-kritische und positive Studie. (12 vols.) Münster in Westfalen: Aschendorff.

- Slavet, E. 2009. Racial Fever: Freud and the Jewish Question. Fordham University Press.

- Slavet, E. 2010. ‘Freud’s Theory of Jewishness For Better and for Worse’. In A.D. Richards (ed.) The Jewish World of Sigmund Freud: Essays on Cultural Roots and the Problem of Religious Identity, 96-111. North Carolina: McFarland & Co.

- Smith, R.J. 2016. ‘Darwin, Freud, and the Continuing Misrepresentation of the Primal Horde’, Current Anthropology 57 (6), 838-843.

- Thornton, S. ‘Projection’, In R.A. Segal and K. von Stuckrad (eds.) Vocabulary for the Study of Religion (vol. 3). Leiden/Boston, 2015, 138-144.

- Tylor, E.B. 1871. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art, and custom (2 vols). London: John Murray.

- Tylor, E.B. 1881. Anthropology: an introduction to the study of man and civilization. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Whitebook, J. 2017. Freud: An Intellectual Autobiography. Cambridge University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1966. Lectures & Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief (ed. C. Barrett). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1974. Philosophical Investigations (trans. G.E.M. Anscombe). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Yerushalmi, Y.H. 1993. Freud’s “Moses”: Judaism Terminable and Interminable. Yale University Press.

9.2 Further Reading

- Alston, W.P