Carbon stands as the fundamental building block of life as we know it. It forms the very structures of our bodies, serves as the energy source in our diets, and underpins our global economies and infrastructures. While carbon is undeniably vital, its cycle is deeply intertwined with pressing global challenges, most notably climate change. However, carbon is not the only element cycling through our environment crucial for life; nitrogen and oxygen are equally essential, each with complex cycles that interact with the carbon cycle and shape our planet.

Carbon is fundamental to life and a major energy source, but it’s part of a larger picture involving nitrogen and oxygen cycles.

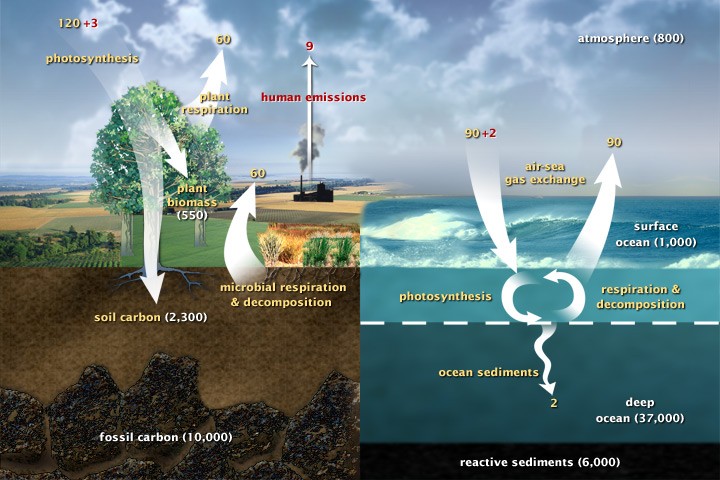

Forged within stars, carbon ranks as the fourth most abundant element in the universe. Earth’s carbon reservoirs are massive, with approximately 65,500 billion metric tons stored in rocks, and the remainder distributed across oceans, the atmosphere, plants, soil, and fossil fuel deposits. These reservoirs are interconnected through the carbon cycle, a system of exchange with both slow and rapid components. Any alterations within this cycle that relocate carbon from one reservoir to another inevitably impact the others. Specifically, the introduction of carbon gases into the atmosphere leads to increased global temperatures, highlighting the delicate balance within this system.

The fast carbon cycle illustrates carbon movement between land, atmosphere, and oceans. Natural fluxes are shown in yellow, human impacts in red (gigatons of carbon/year), and carbon storage in white. (Diagram adapted from U.S. DOE.)

Similar to carbon, both nitrogen and oxygen are cycled through the Earth’s systems via biogeochemical cycles. These cycles describe the pathways and storage locations of these elements, vital for life, as they move through the atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere. Understanding these cycles, and especially comparing them, is crucial for grasping the interconnectedness of Earth’s systems and the profound impact of human activities.

The Carbon Cycle: Foundation of Organic Life and Climate Regulation

The carbon cycle is often categorized into two main timescales: the slow carbon cycle and the fast carbon cycle.

The Slow Carbon Cycle: A Geologic Timescale

Operating over vast spans of 100-200 million years, the slow carbon cycle involves the movement of carbon between rocks, soil, the ocean, and the atmosphere. Annually, it processes 1013 to 1014 grams of carbon. This cycle begins with atmospheric carbon dioxide interacting with water to form carbonic acid, a weak acid present in rainwater. As this acidic rain falls, it facilitates chemical weathering of rocks, releasing ions like calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium. Rivers transport these ions to the ocean.

Rivers transport calcium ions, products of rock weathering, to the ocean, where they contribute to limestone formation. (Photograph ©2009 Greg Carley.)

In the ocean, these calcium ions react with bicarbonate ions to produce calcium carbonate. Marine organisms, such as corals and plankton, utilize calcium carbonate to build shells and skeletons. Upon their death, these organisms settle on the ocean floor, accumulating over time and solidifying into limestone rock, effectively storing carbon for millions of years. Volcanic activity is the primary mechanism for releasing this stored carbon back into the atmosphere. Volcanoes emit carbon dioxide, returning it to the atmosphere and initiating the cycle anew. While volcanoes release between 130 and 380 million metric tons of carbon dioxide yearly, human activities, predominantly the burning of fossil fuels, contribute approximately 30 billion tons annually – a staggering 100 to 300 times greater than volcanic emissions.

The Fast Carbon Cycle: A Biological Timescale

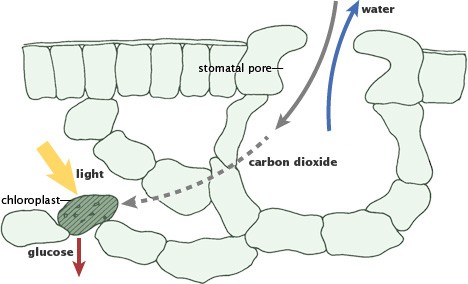

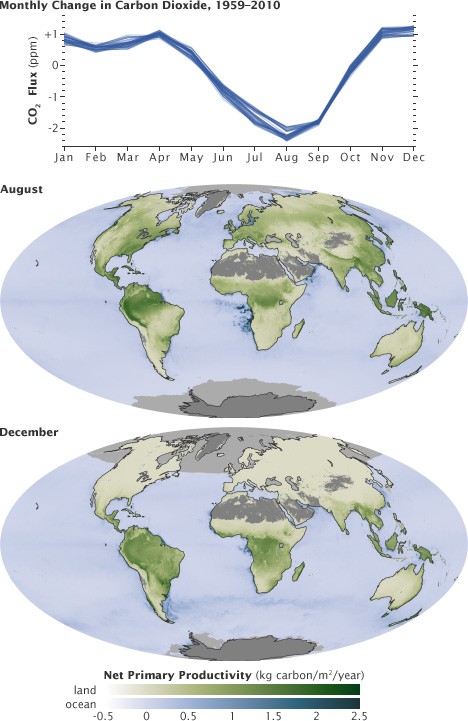

In contrast, the fast carbon cycle operates on a much shorter timescale, measured in lifespans, and is deeply intertwined with biological processes. It involves the movement of carbon through living organisms and the biosphere, cycling between 1015 and 1017 grams of carbon each year. Photosynthesis and respiration are the key processes in this cycle. Plants and phytoplankton absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide for photosynthesis, converting it into organic compounds (sugars) and releasing oxygen.

Photosynthesis forms the basis of the fast carbon cycle, where plants convert carbon dioxide and sunlight into energy. (Illustration adapted from P.J. Sellers et al., 1992.)

This absorbed carbon then moves through the food chain as organisms consume plants. Respiration, the reverse process of photosynthesis, occurs when organisms break down these organic compounds to release energy, returning carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Decomposition of dead organisms also releases carbon back into the environment. This rapid exchange of carbon between the atmosphere and living organisms is evident in seasonal fluctuations of atmospheric carbon dioxide, decreasing during growing seasons and increasing during periods of dormancy and decay.

Seasonal changes in net primary productivity show the fast carbon cycle in action, with carbon dioxide uptake during growth and release during decomposition.

The Nitrogen Cycle: Essential for Protein and Nucleic Acids

Nitrogen, like carbon, is crucial for life, forming a key component of amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) and nucleic acids (DNA and RNA). The nitrogen cycle is a complex biogeochemical process involving several stages, largely driven by microbial activity.

Nitrogen Fixation: Converting Atmospheric Nitrogen

The atmosphere is composed of approximately 78% nitrogen gas (N2), but in this form, nitrogen is largely unusable by most organisms. Nitrogen fixation is the process of converting atmospheric nitrogen into forms that plants can absorb, primarily ammonia (NH3) or ammonium (NH4+). This process is mainly carried out by certain types of bacteria, known as nitrogen-fixing bacteria, which can be free-living in the soil or live in symbiotic relationships with leguminous plants (like beans and peas). Atmospheric nitrogen fixation also occurs to a lesser extent through lightning strikes, which provide the energy needed to convert N2 to nitrogen oxides (NOx), which then react with water to form nitrates (NO3–).

Nitrification and Assimilation: Incorporation into Biomolecules

Once nitrogen is fixed into ammonia or ammonium, nitrification can occur. Nitrification is a two-step microbial process. First, ammonia is converted to nitrite (NO2–) by bacteria like Nitrosomonas. Then, nitrite is further oxidized to nitrate (NO3–) by bacteria such as Nitrobacter. Nitrate is the form of nitrogen most readily assimilated by plants. Assimilation is the process where plants absorb inorganic nitrogen compounds (ammonia, ammonium, or nitrate) from the soil and incorporate them into organic molecules like amino acids and proteins. Animals obtain nitrogen by consuming plants or other animals.

Ammonification and Denitrification: Returning Nitrogen to the Cycle

When organisms die or excrete waste, the organic nitrogen is returned to the soil. Ammonification, also known as mineralization, is the process where decomposers (bacteria and fungi) break down organic nitrogen compounds into ammonia (NH3) or ammonium (NH4+), making it available again for nitrification or plant uptake. Denitrification is the process where denitrifying bacteria convert nitrates (NO3–) back into atmospheric nitrogen gas (N2), completing the cycle. This process is anaerobic and typically occurs in waterlogged soils and sediments.

The Nitrogen Cycle involves fixation, nitrification, assimilation, ammonification, and denitrification, driven largely by microorganisms. (Diagram from Wikimedia Commons)

The Oxygen Cycle: Supporting Respiration and Atmospheric Balance

Oxygen is the third critical element, essential for respiration in most living organisms and making up about 21% of Earth’s atmosphere. The oxygen cycle describes the movement of oxygen through the three main reservoirs: the atmosphere, the biosphere, and the lithosphere.

Photosynthesis: The Primary Source of Atmospheric Oxygen

Photosynthesis is the main process responsible for producing and replenishing atmospheric oxygen. During photosynthesis, plants, algae, and cyanobacteria use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to produce glucose (a sugar) for energy and release oxygen as a byproduct. This process has been crucial in shaping Earth’s atmosphere over billions of years, transforming it from a largely anoxic environment to the oxygen-rich atmosphere we have today.

Respiration and Decomposition: Oxygen Consumption

Respiration, performed by most living organisms, consumes oxygen and releases carbon dioxide and water. This is the reverse process of photosynthesis. Decomposition of organic matter by bacteria and fungi also consumes oxygen. These processes act as major sinks for atmospheric oxygen, balancing the oxygen production from photosynthesis.

Other Oxygen Cycle Processes

Oxygen also participates in various geological and chemical processes. Weathering of rocks releases oxygen from minerals. Ozone (O3) in the stratosphere, formed from oxygen, absorbs harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun, protecting life on Earth. Oxygen also reacts with various elements in the lithosphere, forming oxides.

The Oxygen Cycle is driven by photosynthesis and respiration, with geological and chemical processes also playing a role. (Diagram from Wikimedia Commons)

Comparing and Contrasting the Cycles: Interconnections and Human Impacts

While each cycle operates distinctly, the nitrogen, carbon, and oxygen cycles are intricately linked and influence each other significantly.

Similarities:

- Biogeochemical Cycles: All three are biogeochemical cycles, involving biological, geological, and chemical processes.

- Essential for Life: All three elements are fundamental building blocks of life and are essential for various biological processes.

- Atmospheric Reservoir: The atmosphere serves as a major reservoir for all three elements (N2, CO2, O2).

- Microbial Mediation: Microorganisms play crucial roles in all three cycles, particularly in nutrient transformations and decomposition.

- Human Impact: Human activities have significantly altered all three cycles, leading to environmental consequences.

Differences:

| Feature | Carbon Cycle | Nitrogen Cycle | Oxygen Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Processes | Photosynthesis, Respiration, Combustion, Weathering, Volcanic Activity | Nitrogen Fixation, Nitrification, Denitrification, Ammonification, Assimilation | Photosynthesis, Respiration, Decomposition, Ozone Formation, Weathering |

| Primary Form in Atmosphere | CO2 | N2 | O2 |

| Main Biological Role | Building block of organic molecules, energy source | Component of proteins and nucleic acids | Respiration, energy production |

| Microbial Role | Decomposition, Respiration | Fixation, Nitrification, Denitrification, Ammonification | Decomposition, Photosynthesis (Cyanobacteria) |

| Speed of Cycle | Fast and Slow components | Relatively fast | Fast |

| Major Human Impacts | Fossil fuel burning, deforestation, climate change | Fertilizer production, nitrogen pollution, eutrophication | Deforestation (reducing O2 production), fossil fuel burning (O2 consumption) |

Interconnections:

- Photosynthesis and Respiration Link Carbon and Oxygen: Photosynthesis removes CO2 from the atmosphere and releases O2, while respiration does the opposite, directly linking the carbon and oxygen cycles.

- Nitrogen and Carbon in Ecosystem Productivity: Nitrogen availability often limits plant growth, influencing the amount of carbon dioxide plants can absorb through photosynthesis. Nitrogen fertilization can increase carbon sequestration in vegetation.

- Ocean Acidification (Carbon Cycle Impact on Nitrogen and Oxygen): Increased atmospheric CO2 leads to ocean acidification, which can impact marine nitrogen cycling processes and oxygen levels in the ocean.

- Combustion and all three cycles: Burning fossil fuels (carbon cycle), releases nitrogen oxides (nitrogen cycle), and consumes oxygen (oxygen cycle), directly impacting all three cycles simultaneously.

Human Perturbations and Future Implications

Human activities have significantly disrupted the natural balance of all three cycles, primarily through industrialization and agriculture.

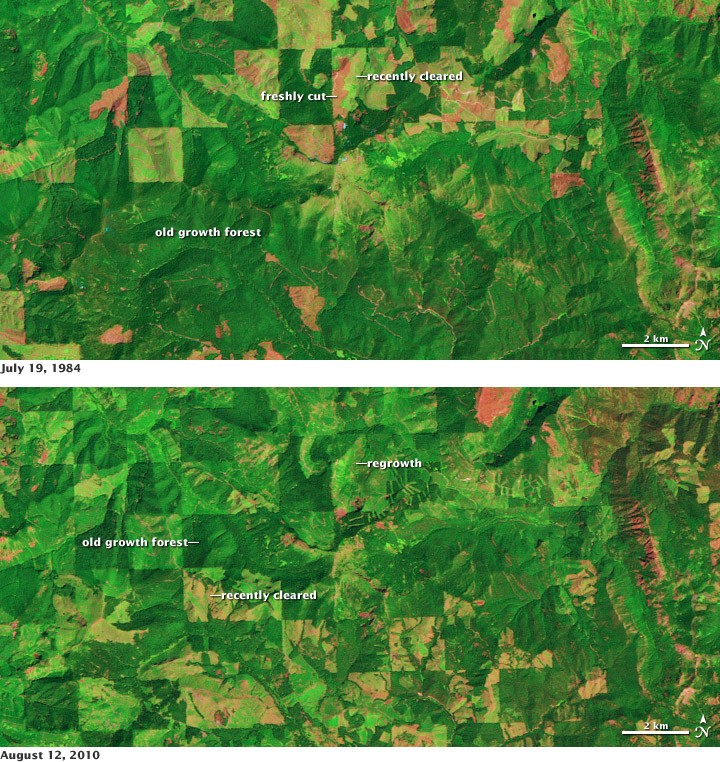

- Carbon Cycle Disruption: Burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and land-use changes have dramatically increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations, leading to global warming and climate change.

- Nitrogen Cycle Disruption: Industrial nitrogen fixation for fertilizer production has more than doubled natural nitrogen fixation rates. This excess reactive nitrogen leads to air and water pollution, eutrophication of water bodies, and greenhouse gas emissions (nitrous oxide, N2O).

- Oxygen Cycle Disruption: While large-scale depletion of atmospheric oxygen is not currently a major concern, deforestation reduces oxygen production, and fossil fuel combustion consumes oxygen. Localized oxygen depletion (hypoxia) in aquatic environments is a growing problem due to nutrient pollution and climate change.

Understanding the intricate connections and individual dynamics of the carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen cycles is paramount. Addressing global environmental challenges like climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss requires a holistic approach that considers the interconnected nature of these fundamental biogeochemical cycles and the profound and multifaceted impacts of human actions on these critical Earth systems.

Satellite data helps monitor changes in forest cover, which impacts all three cycles – carbon storage, oxygen production, and nitrogen cycling within ecosystems.