Understanding Feedback Loops: The Foundation of Biological Regulation

In the intricate world of biology, life processes are governed by a delicate balance, a state of equilibrium known as homeostasis. This maintenance of a stable internal environment, despite external fluctuations, is crucial for the survival of all living organisms. A fundamental mechanism underpinning homeostasis is the feedback loop. Imagine a thermostat in your home; it monitors the temperature and adjusts the heating or cooling system to maintain your desired setting. Biological feedback loops operate on similar principles, acting as sophisticated control systems that regulate a vast array of physiological processes.

A feedback loop is essentially a biological response to a stimulus where the output of a system influences its own activity. This influence can either amplify the initial change or counteract it, pushing the system further away from or back towards its original set point. These two distinct types of feedback mechanisms are known as positive feedback and negative feedback, and understanding their differences is key to grasping how our bodies and ecosystems maintain stability and respond to change. Both are indispensable for life as we know it, playing vital roles from the smallest cellular processes to large-scale ecological dynamics. Let’s delve into a comparative analysis of these essential mechanisms to appreciate their unique functions and significance.

Positive Feedback Mechanisms: Amplifying Change and Driving Processes Forward

Positive feedback loops are characterized by their ability to amplify an initial change, driving a system further away from its starting point or equilibrium. In essence, the output of a positive feedback loop reinforces the initial stimulus, creating a snowball effect. While this might seem counterintuitive to maintaining stability, positive feedback mechanisms are crucial for specific biological processes that require a rapid and amplified response to reach a definitive endpoint. They are less common in maintaining homeostasis compared to negative feedback, but are vital for certain biological events that need to be driven to completion.

Think of positive feedback as an accelerating force. Once initiated, it propels a process forward with increasing intensity until a specific outcome is achieved. These loops are not about maintaining balance but rather about generating a swift and substantial change to accomplish a particular biological task.

Examples of Positive Feedback Loops in Biology

Several critical biological processes rely on the amplifying nature of positive feedback loops. Let’s explore a few prominent examples:

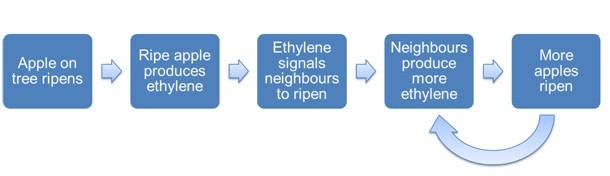

1. Fruit Ripening: A Cascade of Ethylene

The seemingly sudden ripening of fruit on a tree is a fascinating example of a positive feedback loop in the plant kingdom. Imagine an apple tree laden with unripe fruit. The ripening process begins when a single apple starts to mature and release a gaseous plant hormone called ethylene. Ethylene acts as a ripening agent, and as the first apple releases it, the gas diffuses to neighboring unripe apples.

Exposure to ethylene triggers these neighboring apples to also begin ripening and, crucially, to produce their own ethylene. This creates a chain reaction: more ethylene is produced, leading to the accelerated ripening of even more apples. This positive feedback loop continues, with each ripening fruit contributing to the ethylene concentration, until the entire tree’s fruit crop ripens in a relatively short period. This synchronized ripening is beneficial for seed dispersal, ensuring that fruits are ready to be consumed by animals at the optimal time.

2. Childbirth: Oxytocin and Uterine Contractions

Childbirth is perhaps one of the most dramatic and essential examples of positive feedback in mammals. The process of labor and delivery relies heavily on a positive feedback loop involving the hormone oxytocin. As labor begins, the baby’s head descends into the birth canal, exerting pressure on the cervix. This pressure stimulates stretch receptors in the cervix, which then send nerve signals to the brain.

In response, the brain, specifically the hypothalamus, releases oxytocin into the bloodstream. Oxytocin travels to the uterus and stimulates uterine muscles to contract. These contractions, in turn, push the baby further down, increasing pressure on the cervix and stimulating even more oxytocin release. This creates a positive feedback loop: cervical stretch leads to oxytocin release, which leads to stronger contractions, which further increase cervical stretch. This cycle intensifies until the baby is born, breaking the loop. The escalating contractions are a direct result of the positive feedback, ensuring efficient and effective delivery.

Figure 3: Uterine contractions during childbirth are driven by a positive feedback loop involving oxytocin, amplifying the process until delivery.

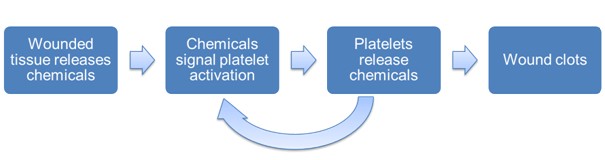

3. Blood Clotting: Platelet Activation Cascade

When tissue is injured, the body’s rapid response to prevent blood loss involves a positive feedback loop in blood clotting. When a blood vessel is damaged, the injured tissue releases chemical signals. These signals initiate the activation of platelets, small cell fragments in the blood that play a crucial role in clotting.

Activated platelets become sticky and adhere to the injury site, forming an initial plug. Critically, activated platelets also release chemicals that further activate more platelets. This creates a positive feedback cascade: the initial platelet activation triggers the activation of more platelets, leading to a rapid and localized amplification of the clotting process. This cascade continues until a stable blood clot is formed, effectively sealing the wound and preventing excessive blood loss. This rapid amplification is essential for quickly stopping bleeding and initiating the repair process.

Negative Feedback Mechanisms: Restoring Balance and Maintaining Homeostasis

In contrast to positive feedback, negative feedback loops are the primary mechanisms for maintaining homeostasis. They work by counteracting an initial change, bringing a system back towards its set point or equilibrium. The output of a negative feedback loop reduces or inhibits the original stimulus, creating a self-regulating system that stabilizes internal conditions.

Think of negative feedback as a corrective force. When a system deviates from its ideal state, negative feedback mechanisms kick in to reverse the direction of change and restore balance. These loops are essential for maintaining stable internal conditions within organisms, from body temperature and blood glucose levels to fluid balance and hormone concentrations.

Examples of Negative Feedback Loops in Biology

Negative feedback loops are ubiquitous in biological systems, regulating a vast array of physiological processes. Let’s examine a few key examples:

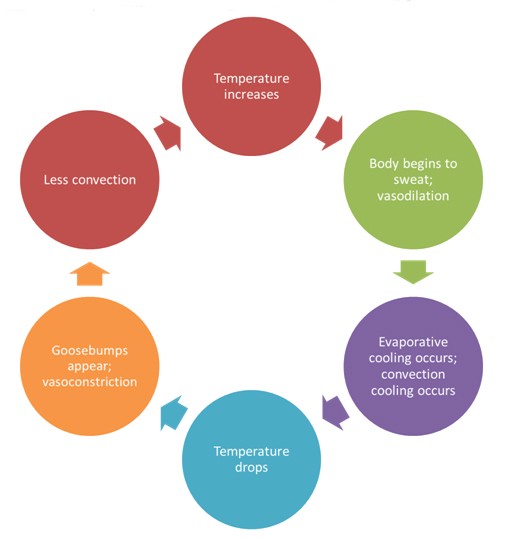

1. Temperature Regulation: Thermostatic Control in Humans

Human body temperature regulation is a classic example of negative feedback. Our bodies strive to maintain a core temperature of approximately 98.6°F (37°C). When body temperature deviates from this set point, negative feedback mechanisms are activated to restore it.

If body temperature rises too high (e.g., during exercise or in hot weather), temperature sensors in the body detect this change and trigger responses to cool down. Sweating is initiated, and as sweat evaporates from the skin, it removes heat, causing evaporative cooling. Vasodilation also occurs, where blood vessels near the skin surface widen, allowing more blood flow to the periphery where heat can be radiated away from the body. These responses work to reduce body temperature back towards the normal range.

Conversely, if body temperature drops too low (e.g., in cold environments), different mechanisms are activated. Shivering is triggered, generating heat through muscle contractions. Vasoconstriction occurs, where blood vessels near the skin surface narrow, reducing blood flow to the periphery and conserving heat. Goosebumps also form, which, while less effective in humans than in furry animals, are a vestigial reflex to trap a layer of insulating air. These responses work to increase body temperature back towards the normal range. This constant back-and-forth regulation ensures that body temperature remains within a narrow and optimal range.

2. Blood Pressure Regulation (Baroreflex): Maintaining Vascular Tone

Maintaining stable blood pressure is crucial for ensuring adequate blood flow to all organs and tissues. The baroreflex is a rapid negative feedback loop that regulates blood pressure. Baroreceptors, specialized pressure sensors located in the walls of major arteries like the carotid artery and aorta, continuously monitor blood pressure.

If blood pressure rises too high, baroreceptors detect this increase and send signals to the brainstem. The brainstem then initiates responses to lower blood pressure. Heart rate is decreased, and blood vessels are signaled to dilate (vasodilation), reducing resistance to blood flow. These actions work to bring blood pressure back down to the normal range.

Conversely, if blood pressure drops too low, baroreceptors detect this decrease and signal the brainstem to initiate responses to raise blood pressure. Heart rate is increased, and blood vessels are signaled to constrict (vasoconstriction), increasing resistance to blood flow. These actions work to bring blood pressure back up to the normal range. The baroreflex is a rapid and sensitive negative feedback loop that constantly adjusts heart rate and vascular tone to maintain blood pressure within a healthy range.

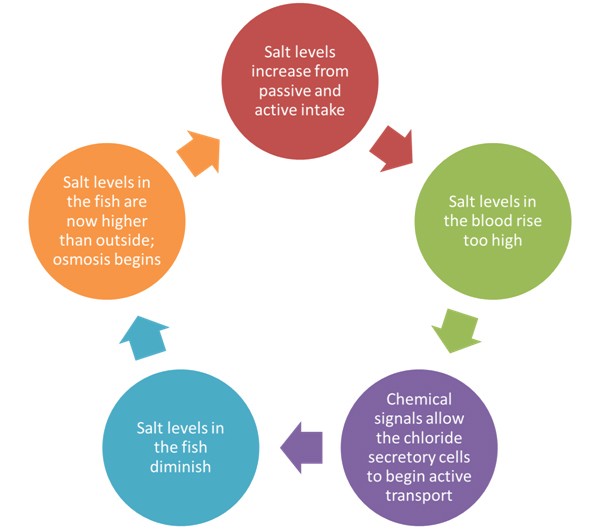

3. Osmoregulation: Balancing Fluid and Electrolyte Concentrations

Osmoregulation refers to the maintenance of a stable internal osmotic pressure and fluid balance within an organism. This is critical for cell function and overall homeostasis. Let’s consider the example of a saltwater fish to illustrate negative feedback in osmoregulation.

Saltwater fish live in a hypertonic environment, meaning the surrounding seawater has a higher salt concentration than their body fluids. This creates a tendency for water to move out of their bodies and for salt to move in, due to osmosis and diffusion. To counteract this, saltwater fish employ negative feedback mechanisms to maintain their internal fluid and electrolyte balance.

When a saltwater fish starts to lose too much water or accumulate too much salt, osmoreceptors in the brain detect these changes. In response, the fish may drink more water to compensate for water loss. Crucially, their gills actively excrete excess salt into the surrounding seawater through specialized chloride secretory cells. They also produce very concentrated urine to minimize water loss and further excrete salts. These responses are continuously adjusted based on feedback from osmoreceptors, ensuring that the fish maintains a stable internal salt and water concentration despite the challenging external environment.

4. Blood Glucose Regulation: Insulin and Glucagon’s Balancing Act

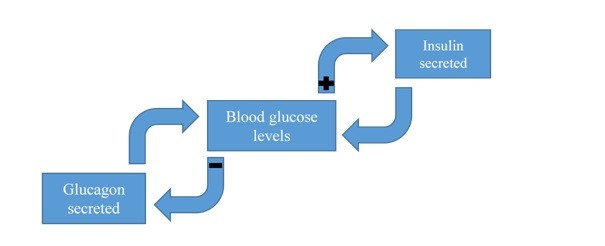

Blood glucose regulation is another vital negative feedback loop, essential for providing cells with a constant energy supply. The hormones insulin and glucagon, produced by the pancreas, play key roles in this regulation.

When blood glucose levels rise too high (e.g., after a meal), specialized beta cells in the pancreas detect this increase and release insulin. Insulin acts to lower blood glucose by promoting glucose uptake into cells (especially muscle and liver cells) and stimulating the storage of glucose as glycogen in the liver. This action brings blood glucose levels back down towards the normal range.

Conversely, when blood glucose levels drop too low (e.g., during fasting or prolonged exercise), alpha cells in the pancreas detect this decrease and release glucagon. Glucagon acts to raise blood glucose by stimulating the breakdown of glycogen into glucose in the liver and promoting the release of glucose into the bloodstream. This action brings blood glucose levels back up towards the normal range. The opposing actions of insulin and glucagon, regulated by negative feedback, ensure that blood glucose levels are tightly controlled within a narrow range, providing a stable energy supply for the body.

Positive vs. Negative Feedback: Key Distinctions Summarized

| Feature | Positive Feedback | Negative Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Response to Change | Amplifies the initial change | Counteracts the initial change |

| Direction of Change | Moves system further away from equilibrium | Moves system back towards equilibrium |

| Goal | Drive a process to completion, amplify a response | Maintain stability, restore homeostasis, regulate a variable |

| Effect on Output | Increases production/response | Decreases production/response |

| Stability | Tends to be less stable, can lead to rapid changes | Promotes stability, maintains steady state |

| Commonality in Homeostasis | Less common in direct homeostasis maintenance | More common and crucial for homeostasis maintenance |

| Examples | Fruit ripening, childbirth, blood clotting | Temperature regulation, blood pressure, osmoregulation, blood glucose |

The Vital Significance of Feedback Mechanisms in Biology

Feedback mechanisms, both positive and negative, are absolutely essential for life. Negative feedback loops are fundamental to homeostasis, enabling organisms to maintain stable internal conditions necessary for cellular function and survival. Without negative feedback, our body temperature, blood pressure, blood glucose, and countless other variables would fluctuate wildly, leading to physiological chaos and ultimately death.

While less frequent, positive feedback loops are equally important for specific biological processes that require rapid amplification and completion. Childbirth, blood clotting, and even some aspects of immune responses rely on positive feedback to achieve their intended outcomes efficiently.

Disruptions in feedback loops can have serious consequences for health. For example, diabetes mellitus is a condition characterized by dysfunctional blood glucose regulation. In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas fails to produce insulin (a key component of the negative feedback loop regulating blood glucose). In type 2 diabetes, cells become resistant to insulin. In both cases, the negative feedback loop is impaired, leading to chronically elevated blood glucose levels and a range of health complications. Similarly, malfunctions in other feedback loops can contribute to various diseases and disorders.

Wrapping Up: The Elegance of Biological Regulation

In conclusion, both positive and negative feedback mechanisms are crucial control systems in biology. While they operate in fundamentally different ways – one amplifying change and the other counteracting it – both are indispensable for maintaining life. Negative feedback is the cornerstone of homeostasis, ensuring stability and balance, while positive feedback plays vital roles in specific processes requiring rapid and amplified responses. Understanding these feedback loops provides a deeper appreciation for the remarkable complexity and self-regulating nature of biological systems, highlighting the elegant mechanisms that allow life to thrive in a dynamic and ever-changing world.