Every organism on Earth is classified into one of two fundamental groups: prokaryotes or eukaryotes. The defining factor for this classification is their cellular structure. Prokaryotic cells are simple, unicellular organisms lacking a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. Bacteria and archaea are examples of prokaryotes. Eukaryotic cells, often found in multicellular organisms, are more complex. They possess a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles that compartmentalize cellular functions. Animals, plants, fungi, algae, and protozoa are all eukaryotes.

This article provides an in-depth comparison of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, highlighting their similarities and, more importantly, their key differences. Understanding these distinctions is crucial in grasping the diversity of life and the evolution of cellular complexity.

Comparing Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

Prokaryotes are considered to be the earliest forms of life, with eukaryotes believed to have evolved from them approximately 2.7 billion years ago. The widely accepted theory of eukaryotic evolution is endosymbiosis, which suggests that eukaryotes arose from a symbiotic merger of two or more prokaryotic cells. This process is thought to have led to the development of membrane-bound organelles like mitochondria, providing eukaryotic ancestors with the energy necessary for developing into the complex cells we recognize today.

However, recent scientific discoveries are challenging and refining our understanding of this evolutionary narrative. Research has revealed prokaryotic bacteria capable of phagocytosis – “eating” other cells – a process previously thought to be exclusive to eukaryotes. This finding necessitates a re-evaluation of theories surrounding the origins of eukaryotes and highlights the dynamic nature of scientific understanding in cell biology.

The most fundamental distinction between prokaryotes and eukaryotes lies in the presence of a nucleus. Eukaryotic cells are defined by their membrane-bound nucleus, which houses their genetic material. In contrast, prokaryotic cells lack a nucleus; their DNA is located in a nucleoid region, a central area within the cell but not enclosed by a membrane.

Beyond the nucleus, eukaryotes are characterized by a multitude of membrane-bound organelles, each performing specialized functions within the cell. Prokaryotes, on the other hand, are devoid of such organelles. Another significant difference is in their DNA structure and organization. Eukaryotic DNA is linear and organized into multiple chromosomes within the nucleus, while prokaryotic DNA is typically circular and located in the cytoplasm. It is important to note that exceptions exist, with linear plasmids and chromosomes found in some prokaryotes, demonstrating the ongoing complexity and nuances being discovered in cellular biology.

Key Similarities Between Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

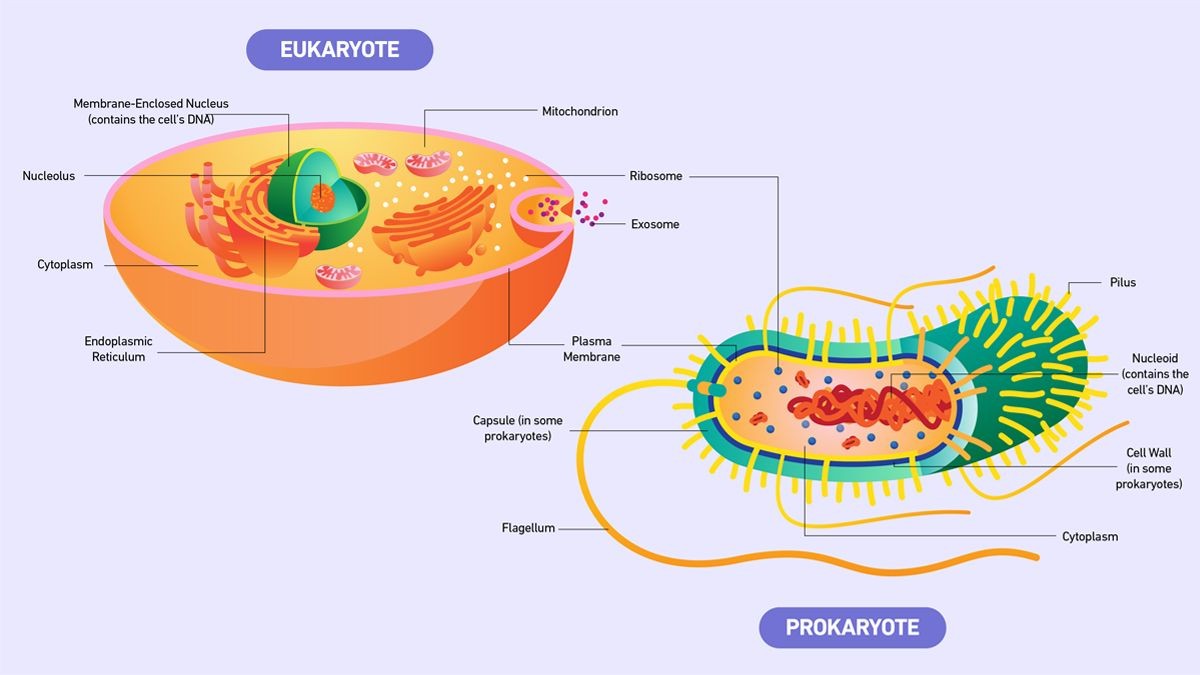

Despite their significant differences, prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells share fundamental characteristics, reflecting their common ancestry and the basic requirements for life. These shared features, illustrated in Figure 1, include:

- DNA: Both cell types utilize DNA as their genetic material, carrying the instructions for cellular functions and heredity. This universal genetic code underscores the interconnectedness of all life forms.

- Plasma Membrane: A plasma membrane, also known as the cell membrane, encloses both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. This outer boundary acts as a selective barrier, regulating the passage of substances in and out of the cell and maintaining cellular integrity.

- Cytoplasm: Both cell types possess cytoplasm, the gel-like substance within the cell membrane. Cytoplasm is where various cellular processes occur, including metabolic reactions and the transport of molecules.

- Ribosomes: Ribosomes are essential for protein synthesis in all cells. Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells contain ribosomes, although there are slight structural differences between them. Ribosomes translate genetic information encoded in messenger RNA (mRNA) into proteins, the workhorses of the cell.

Figure 1: A comparison highlighting the shared and distinct features of prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Credit: Technology Networks.

Key Differences Between Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

Prokaryotes and eukaryotes diverge significantly in several key aspects, primarily in their structural organization and complexity. These differences, summarized in Table 1, dictate their distinct functionalities and roles in the biosphere.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells.

| Feature | Prokaryote | Eukaryote |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | Absent | Present |

| Membrane-bound Organelles | Absent | Present |

| Cell Structure | Unicellular | Predominantly multicellular; some unicellular forms exist |

| Cell Size | Typically smaller (0.1–5 μm), with the exception of a recently discovered centimeter-long bacterium in a mangrove swamp. | Larger (10–100 μm) |

| Complexity | Simpler | More complex |

| DNA Form | Often circular, though linear plasmids and chromosomes are found in some prokaryotes. | Linear |

| Examples | Bacteria, Archaea | Animals, Plants, Fungi, Protists |

| Transcription & Translation | Coupled: translation begins during mRNA synthesis. | Uncoupled: Transcription in the nucleus, translation in the cytoplasm. |

| Ribosome Size | Smaller ribosomes (70S) | Larger ribosomes (80S) |

| Cell Wall | Almost always present; chemically complex (e.g., peptidoglycan in bacteria) | Present in plant cells (cellulose) and fungal cells (chitin), absent in animal cells and some protists; chemically simpler when present |

| Cytoskeleton | Less complex cytoskeleton, primarily involved in cell shape and division | Complex cytoskeleton made of actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments; involved in cell shape, movement, and organization |

Transcription and Translation: Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

A fundamental difference in gene expression lies in the coupling of transcription and translation. In prokaryotic cells, these two processes are coupled. Because there is no nucleus to separate the DNA from the ribosomes, translation of mRNA can begin even before transcription is complete. This allows for rapid gene expression in response to environmental changes.

In eukaryotic cells, transcription and translation are uncoupled. Transcription occurs within the nucleus, where DNA is located, and results in the production of mRNA. This mRNA then must be transported out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where ribosomes are located, for translation to occur. This separation provides eukaryotes with more control over gene expression but adds a layer of complexity absent in prokaryotes.

Prokaryotic Cells: Definition and Features

Prokaryotes encompass two domains of life: Bacteria and Archaea. These are unicellular organisms characterized by the absence of membrane-bound organelles. Prokaryotic cells are generally small and simple, typically ranging from 0.1 to 5 μm in diameter.

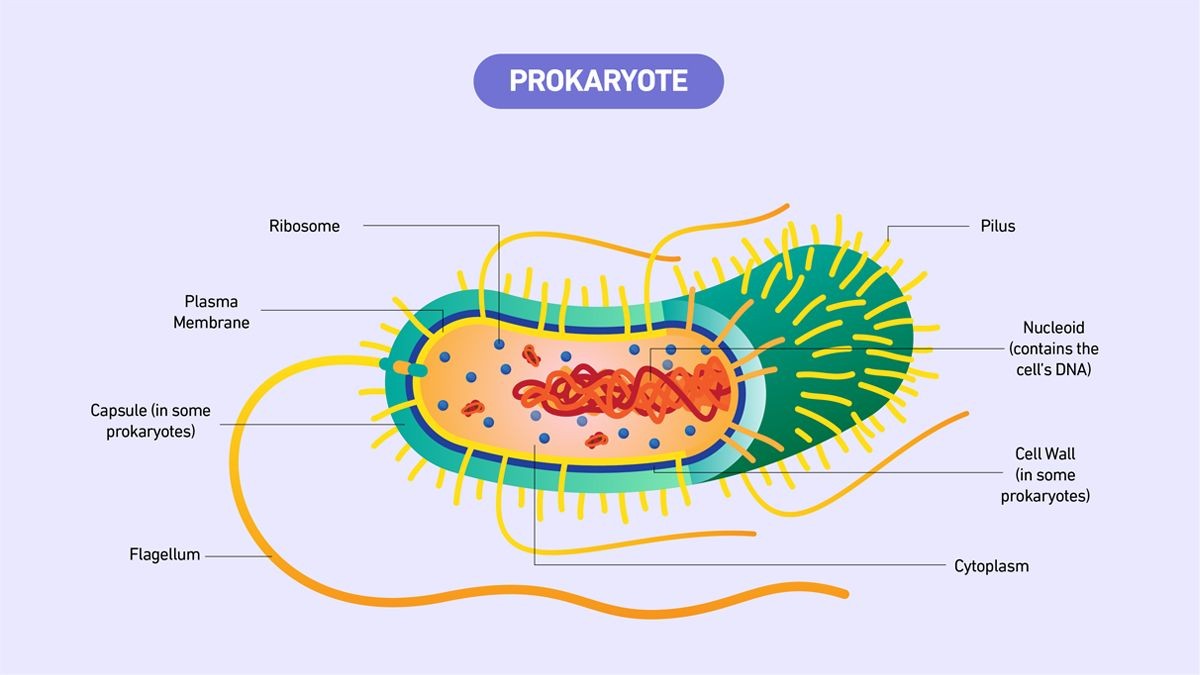

Figure 2: Illustrative diagram of a prokaryotic cell highlighting key structures. Credit: Technology Networks.

Despite lacking membrane-bound organelles, prokaryotic cells are not simply bags of cytoplasm. They exhibit distinct regions and structures. The DNA in prokaryotes is concentrated in the nucleoid region. While not membrane-bound, this region organizes the genetic material. Furthermore, prokaryotes may contain primitive organelles, sometimes referred to as bacterial microcompartments, which provide localized environments for specific metabolic processes, adding a degree of organization within the seemingly simple prokaryotic cell.

Key Features of Prokaryotic Cells

A typical prokaryotic bacterial cell (as depicted in Figure 2) includes the following features:

- Nucleoid: The central region containing the cell’s DNA, which is typically a single circular chromosome.

- Ribosomes: Responsible for protein synthesis, scattered throughout the cytoplasm.

- Cell Wall: A rigid outer layer providing structural support and protection. In bacteria, this wall is primarily composed of peptidoglycans.

- Plasma Membrane: The inner membrane enclosing the cytoplasm, regulating the passage of molecules.

- Capsule: An outer layer in some bacteria, composed of carbohydrates, aiding in attachment and protection.

- Pili (Fimbriae): Hair-like appendages involved in attachment to surfaces and DNA transfer between bacteria.

- Flagella: Tail-like structures facilitating cellular movement.

Examples of Prokaryotes

The two primary domains of prokaryotic life are:

- Bacteria: An incredibly diverse group inhabiting a vast range of environments, playing crucial roles in ecosystems, from nutrient cycling to causing diseases.

- Archaea: Often found in extreme environments (e.g., hot springs, salt lakes), archaea share some similarities with both bacteria and eukaryotes, representing a distinct branch of life.

Nucleus in Prokaryotes?

Prokaryotes do not have a nucleus. Their DNA resides in the nucleoid region, which is not enclosed by a nuclear membrane. This lack of a nucleus is a defining characteristic of prokaryotic cells.

Mitochondria in Prokaryotes?

Prokaryotes do not have mitochondria or any other membrane-bound organelles like the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus. Mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell, are exclusive to eukaryotic cells.

Eukaryotic Cells: Definition and Features

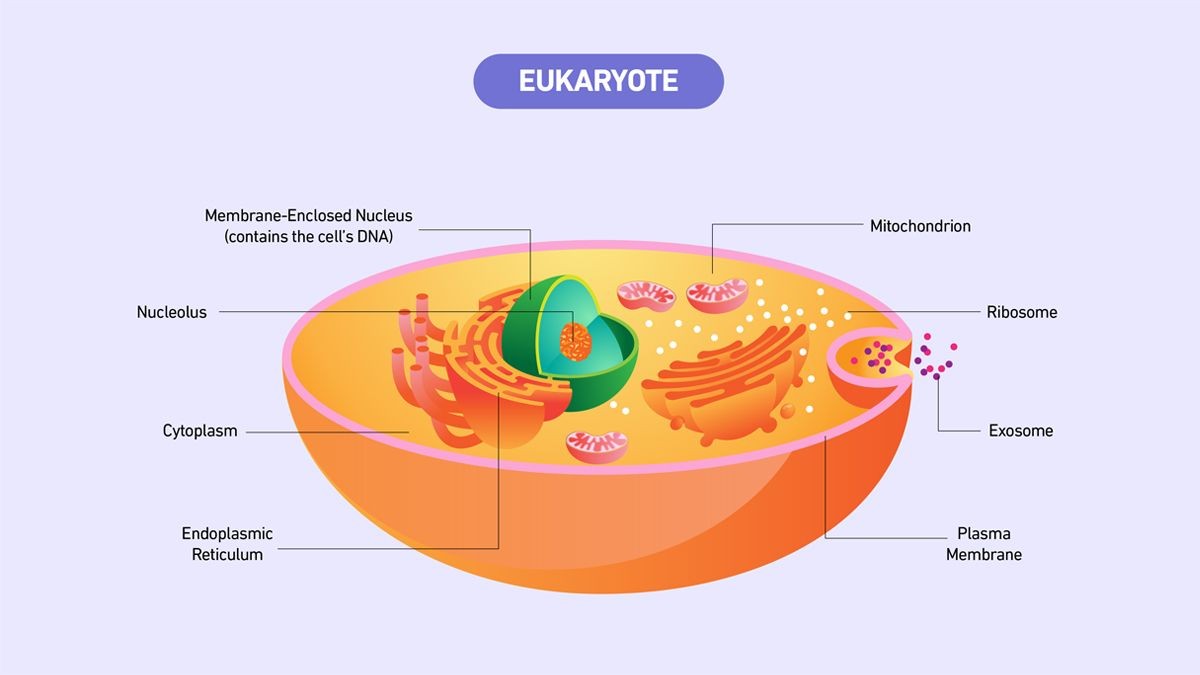

Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells are characterized by the presence of a nucleus and other organelles enclosed within membranes (Figure 3). These organelles compartmentalize cellular functions, allowing for greater complexity and efficiency.

Figure 3: Diagram illustrating the key structures within a eukaryotic cell. Credit: Technology Networks.

Eukaryotic cells are typically larger and more complex than prokaryotic cells, ranging from 10 to 100 μm in diameter. While the majority of eukaryotes are multicellular, unicellular eukaryotic organisms also exist, showcasing the diversity within this domain.

Key Features of Eukaryotic Cells

Eukaryotic cells are characterized by a complex internal organization with numerous membrane-bound organelles. Key components include:

- Nucleus: The control center of the cell, containing the cell’s DNA organized into linear chromosomes within a double membrane.

- Nucleolus: A region within the nucleus responsible for ribosomal RNA (rRNA) synthesis.

- Plasma Membrane: The outer boundary of the cell, similar to prokaryotes, regulating molecular traffic.

- Cytoskeleton: A complex network of protein filaments (actin filaments, microtubules, intermediate filaments) providing structural support, facilitating cell movement and organelle organization.

- Cell Wall: Present in plant cells (cellulose) and fungal cells (chitin), providing rigidity and support; absent in animal cells.

- Ribosomes: Larger ribosomes (80S) compared to prokaryotes, responsible for protein synthesis.

- Mitochondria: The “powerhouses” of the cell, generating ATP through cellular respiration.

- Cytoplasmic Space: The region between the nuclear envelope and plasma membrane.

- Cytoplasm: The entire internal volume excluding the nucleus, encompassing the cytosol and all organelles.

- Cytosol: The gel-like fluid within the cytoplasm, excluding organelles.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): A network of membranes involved in protein and lipid synthesis and transport. Can be rough (with ribosomes) or smooth (without ribosomes).

- Vesicles and Vacuoles: Membrane-bound sacs involved in transport, storage, and waste disposal.

Other organelles commonly found in eukaryotes include the Golgi apparatus (protein processing and sorting), chloroplasts (photosynthesis in plant cells and algae), and lysosomes (cellular digestion).

Examples of Eukaryotes

The domain Eukarya encompasses a wide range of organisms, including:

- Animals: Multicellular, heterotrophic organisms.

- Plants: Multicellular, autotrophic organisms capable of photosynthesis.

- Fungi: Mostly multicellular, heterotrophic organisms with chitinous cell walls.

- Algae: Diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotes, both unicellular and multicellular.

- Protozoans: Unicellular, heterotrophic eukaryotes.

References

- Cooper GM. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9841/. Accessed January 29, 2025.

- Archibald JM. Endosymbiosis and eukaryotic cell evolution. Curr Biol. 2015;25(19):R911-R921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.055

- Wurzbacher Carmen E., Hammer Jonathan, Haufschild Tom, Wiegand Sandra, Kallscheuer Nicolai, Jogler Christian. “Candidatus Uabimicrobium helgolandensis”—a planctomycetal bacterium with phagocytosis-like prey cell engulfment, surface-dependent motility, and cell division. mBio. 2024;15(10):e02044-24. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02044-24

- Karlin S, Mrázek J. Compositional differences within and between eukaryotic genomes. PNAS. 1997;94(19):10227-10232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10227

- Hinnebusch J, Tilly K. Linear plasmids and chromosomes in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10(5):917-922. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00963.x

- Webster MW, Weixlbaumer A. The intricate relationship between transcription and translation. PNAS. 2021;118(21):e2106284118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106284118

- Secaira-Morocho H, Chede A, Gonzalez-de-Salceda L, Garcia-Pichel F, Zhu Q. An evolutionary optimum amid moderate heritability in prokaryotic cell size. Cell Rep. 2024;43(6):114268. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114268

- Cole LA. Biology of Life. Academic Press; 2016:93-99. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128096857000137. Accessed January 29, 2025.

- Simon M, Plattner H. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. Academic Press; 2014:141-198. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B978012800255100003X. Accessed January 29, 2025.