Every living organism on Earth is categorized into one of two fundamental groups: prokaryotes or eukaryotes. This classification hinges on their cellular structure, which dictates their biological functionalities and complexities. Prokaryotes, encompassing bacteria and archaea, are typically unicellular organisms characterized by their lack of a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. In contrast, eukaryotes, which include animals, plants, fungi, algae, and protozoans, are often multicellular and distinguished by the presence of a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles that compartmentalize cellular tasks.

This article delves into a detailed comparison of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, highlighting both their similarities and, more importantly, their key differences. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for grasping the fundamental principles of biology and the evolution of life itself.

Key Differences Between Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

The distinction between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is primarily defined by their internal organization, particularly the presence or absence of a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. These structural differences lead to significant variations in their size, complexity, and biological processes.

Nucleus

The most prominent difference is the nucleus. Eukaryotic cells are defined by having a nucleus, a membrane-bound compartment that houses the cell’s DNA. This nucleus protects the genetic material and provides a controlled environment for DNA replication and transcription. Prokaryotic cells, conversely, lack a nucleus. Their DNA is located in a region called the nucleoid, which is not enclosed by a membrane and resides within the cytoplasm.

Membrane-Bound Organelles

Eukaryotes are characterized by a multitude of membrane-bound organelles, such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and peroxisomes. These organelles compartmentalize cellular functions, enhancing efficiency and allowing for more complex biochemical processes. Prokaryotes lack these membrane-bound organelles. Their cellular processes occur within the cytoplasm without the same level of compartmentalization.

Cell Structure and Size

Prokaryotes are predominantly unicellular, although some can form colonies. They are generally smaller in size, ranging from 0.1 to 5 micrometers (µm) in diameter. This smaller size facilitates a high surface area-to-volume ratio, which is advantageous for nutrient uptake and waste removal in their simple environments. However, exceptions exist, such as the recently discovered centimeter-long bacterium Thiomargarita magnifica.

Eukaryotes are often multicellular, forming complex organisms, although unicellular eukaryotes like yeast and protists also exist. Eukaryotic cells are significantly larger, typically ranging from 10 to 100 µm. This larger size is made possible by their internal compartmentalization and more complex cytoskeletal structures.

Complexity

Due to the lack of organelles and a nucleus, prokaryotic cells are considered simpler in structure and organization compared to eukaryotes. Their metabolic processes, while diverse and efficient, are less compartmentalized.

Eukaryotic cells exhibit a much higher degree of complexity. The presence of numerous organelles allows for specialized functions within the cell and more intricate regulatory mechanisms. This complexity is essential for the development of multicellular organisms and their diverse functions.

DNA Structure and Organization

Eukaryotic DNA is linear and organized into multiple chromosomes, which are located within the nucleus. The DNA is associated with histone proteins, forming chromatin.

Prokaryotic DNA is typically circular, forming a single chromosome. It is located in the nucleoid region and is not associated with histones in the same way as eukaryotic DNA, although histone-like proteins are present in archaea. However, it is important to note that linear plasmids and chromosomes have been found in some prokaryotes, indicating some diversity in prokaryotic DNA organization.

Transcription and Translation

In prokaryotes, transcription and translation are coupled. Because there is no nucleus, ribosomes can attach to the messenger RNA (mRNA) while it is still being transcribed from DNA. This allows for rapid protein synthesis.

In eukaryotes, transcription and translation are uncoupled. Transcription occurs in the nucleus, where mRNA is synthesized and processed. The mature mRNA then exits the nucleus and moves to the cytoplasm, where translation by ribosomes takes place. This separation in space and time allows for more complex regulation of gene expression in eukaryotes.

| Feature | Prokaryote | Eukaryote |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | Absent | Present |

| Membrane-bound Organelles | Absent | Present |

| Cell Structure | Unicellular | Mostly multicellular; some unicellular |

| Cell Size | Typically smaller (0.1–5 μm) | Larger (10–100 μm) |

| Complexity | Simpler | More complex |

| DNA Form | Circular (mostly), linear plasmids possible | Linear |

| Transcription/Translation | Coupled | Uncoupled |

| Examples | Bacteria, Archaea | Animals, Plants, Fungi, Protists |

Key Similarities Between Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

Despite the significant differences, prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells share fundamental characteristics that reflect their common ancestry and the basic requirements for life. All cells, regardless of their classification, must perform essential functions to survive and reproduce.

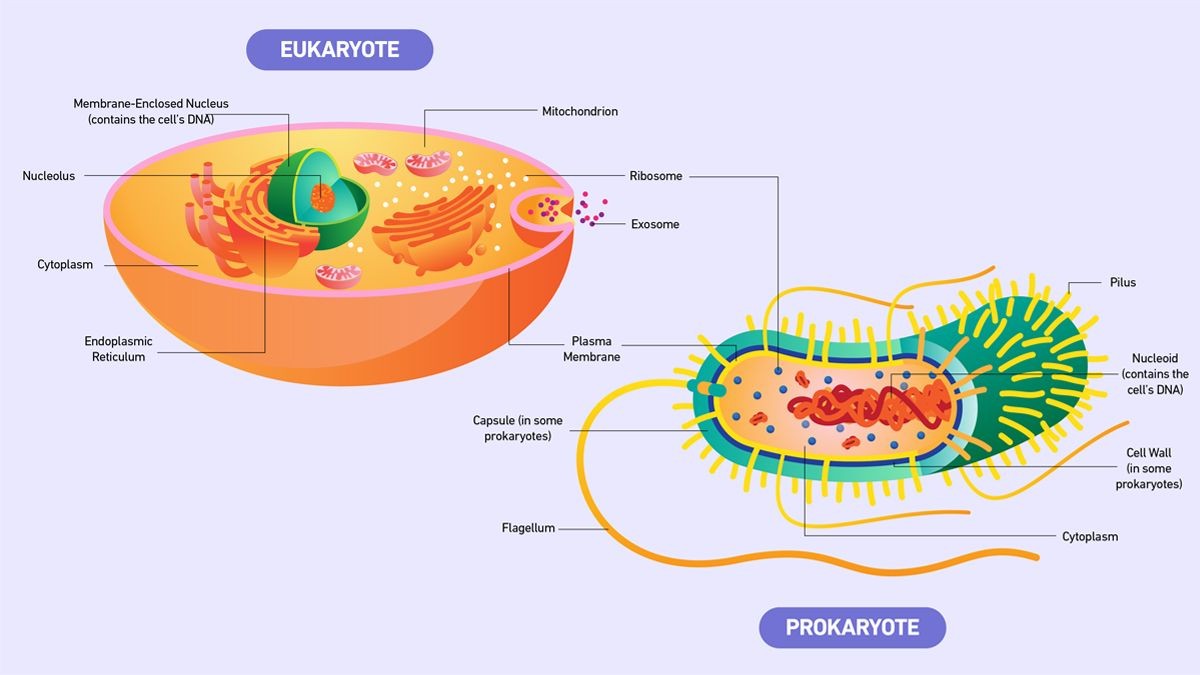

Figure 1: Shared and unique features of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Credit: Technology Networks.

As illustrated in Figure 1, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells possess the following core components:

-

DNA: Both cell types use DNA as their genetic material. DNA carries the hereditary information that dictates cellular functions and characteristics. While the structure and organization of DNA differ, its fundamental role as the blueprint of life is universal.

-

Plasma Membrane: All cells are enclosed by a plasma membrane (or cell membrane). This membrane acts as a selective barrier, controlling the passage of substances into and out of the cell. It is composed of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins and is crucial for maintaining cellular integrity and regulating interactions with the external environment.

-

Cytoplasm: Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells contain cytoplasm. This gel-like substance fills the cell and is where many metabolic reactions occur. In eukaryotes, the cytoplasm includes the cytosol and all organelles except for the nucleus. In prokaryotes, the cytoplasm encompasses everything within the plasma membrane, including the nucleoid and ribosomes.

-

Ribosomes: Ribosomes are essential for protein synthesis in all cells. These molecular machines read the mRNA sequence and translate it into proteins. Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have ribosomes, although there are slight differences in their structure (eukaryotic ribosomes are slightly larger and more complex).

Prokaryotic Cells: A Closer Look

Prokaryotes, classified into Bacteria and Archaea domains, are unicellular organisms that are the most ancient forms of life. They are characterized by their simple structure and absence of membrane-bound organelles, yet they exhibit remarkable metabolic diversity and adaptability. Prokaryotic cells are typically small, ranging from 0.1 to 5 µm in diameter, allowing for rapid growth and reproduction.

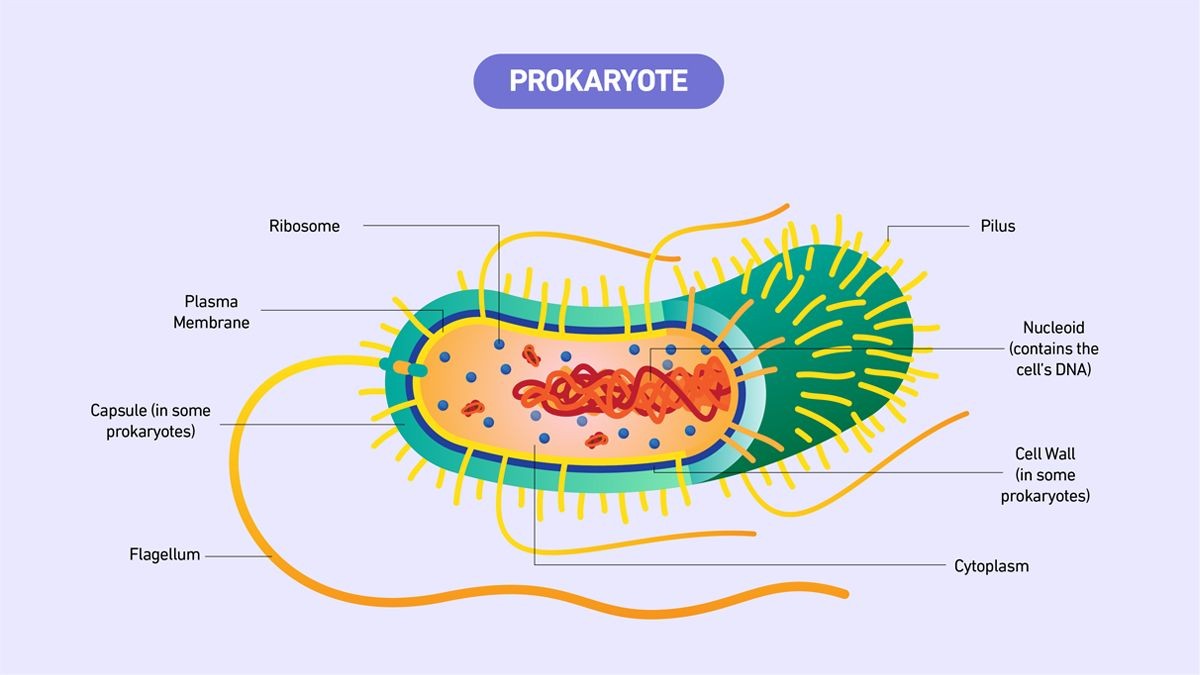

Figure 2: Key structural components of a prokaryotic cell. Credit: Technology Networks.

Figure 2 provides a detailed view of the typical structures found in a prokaryotic bacterial cell:

Key Features of Prokaryotic Cells:

- Nucleoid: The central region containing the cell’s DNA, but it is not membrane-bound like a nucleus. The DNA is typically a circular chromosome.

- Ribosomes: Responsible for protein synthesis, scattered throughout the cytoplasm.

- Cell Wall: A rigid outer layer that provides structural support and protection. In bacteria, the cell wall is primarily composed of peptidoglycans. Archaea have different cell wall compositions, lacking peptidoglycans.

- Plasma Membrane: The inner membrane that encloses the cytoplasm and regulates the passage of molecules.

- Capsule: An outer layer found in some bacteria, composed of polysaccharides. It aids in attachment to surfaces and provides protection from dehydration and immune responses.

- Pili (Fimbriae): Hair-like appendages involved in attachment to surfaces, other cells, and DNA transfer (conjugation).

- Flagella: Tail-like structures that enable motility. Prokaryotic flagella are simpler in structure compared to eukaryotic flagella.

Examples of Prokaryotes

The two domains of prokaryotes are:

- Bacteria: A vast and diverse group, inhabiting virtually every environment on Earth. They play crucial roles in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and some are pathogens. Examples include Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Archaea: Often found in extreme environments, such as hot springs, salt lakes, and anaerobic conditions. They are distinct from bacteria in their genetic makeup and biochemistry. Examples include methanogens, halophiles, and thermophiles.

Nucleus and Mitochondria in Prokaryotes

As previously emphasized, prokaryotes do not possess a nucleus or mitochondria, nor any other membrane-bound organelles. Their cellular functions are carried out within the cytoplasm, often with remarkable efficiency despite the lack of compartmentalization. Energy production in prokaryotes occurs across the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm, rather than in mitochondria.

Eukaryotic Cells: A Closer Look

Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells are characterized by a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. This complex internal organization allows for a greater degree of cellular specialization and efficiency, enabling the development of multicellularity and complex life forms. Eukaryotic cells are generally larger than prokaryotic cells, ranging from 10 to 100 µm.

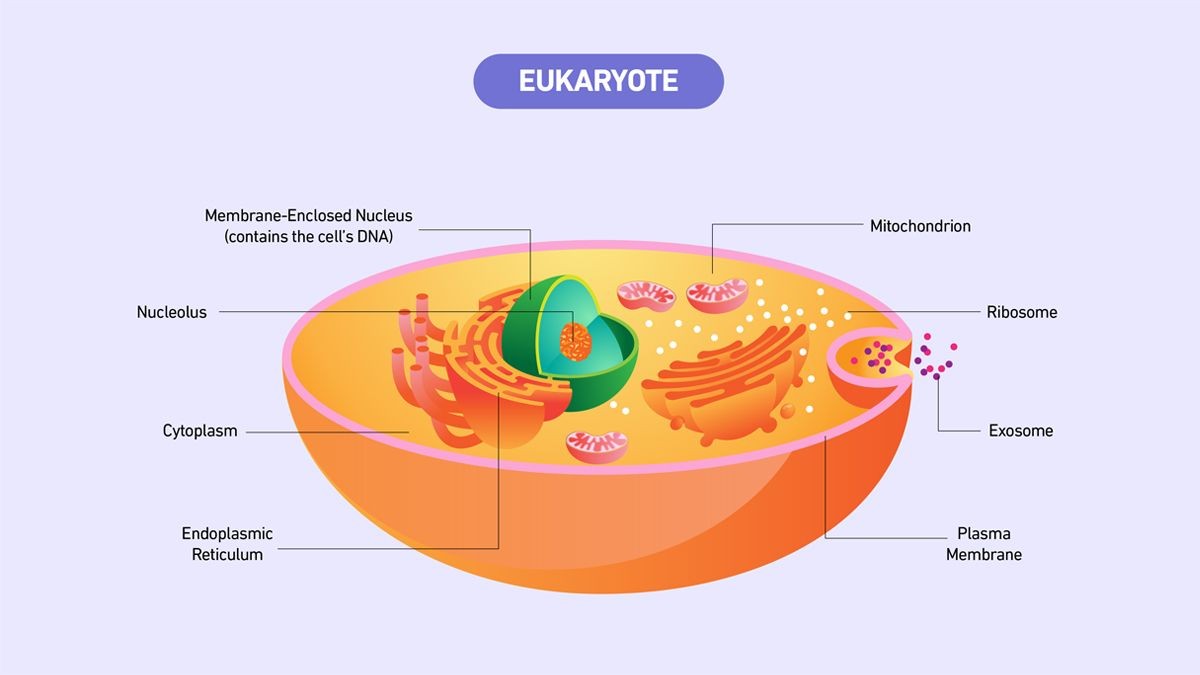

Figure 3: Essential structures within a eukaryotic cell. Credit: Technology Networks.

Figure 3 illustrates the intricate organization of a eukaryotic cell and its various organelles:

Key Features of Eukaryotic Cells:

- Nucleus: The control center of the cell, containing the DNA organized into linear chromosomes. It is enclosed by a double membrane called the nuclear envelope.

- Nucleolus: A region within the nucleus responsible for ribosome RNA (rRNA) synthesis.

- Plasma Membrane: The outer boundary of the cell, similar in function to the prokaryotic plasma membrane.

- Cytoskeleton: A network of protein filaments (actin filaments, microtubules, intermediate filaments) that provides structural support, cell shape, and facilitates movement.

- Cell Wall: Present in plant cells, fungi, and some protists, but absent in animal cells. It provides rigidity and protection. Plant cell walls are made of cellulose, while fungal cell walls are made of chitin.

- Ribosomes: Sites of protein synthesis, found free in the cytoplasm and bound to the endoplasmic reticulum. Eukaryotic ribosomes are larger than prokaryotic ribosomes.

- Mitochondria: The “powerhouses of the cell,” responsible for generating ATP through cellular respiration. They have a double membrane and their own DNA, supporting the endosymbiotic theory of eukaryotic evolution.

- Cytoplasmic Space: The region between the nuclear envelope and the plasma membrane.

- Cytoplasm: The entire internal volume of the cell, excluding the nucleus. It includes the cytosol and all organelles.

- Cytosol: The gel-like fluid portion of the cytoplasm, excluding organelles.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): A network of membranes involved in protein and lipid synthesis, folding, and transport. There are two types: rough ER (studded with ribosomes) and smooth ER (lacking ribosomes).

- Golgi Apparatus: Processes and packages proteins and lipids synthesized in the ER.

- Lysosomes: Contain hydrolytic enzymes for degrading cellular waste and debris.

- Peroxisomes: Involved in various metabolic pathways, including fatty acid oxidation and detoxification.

- Vesicles and Vacuoles: Membrane-bound sacs for transport and storage of various substances. Vacuoles are larger and have storage functions, particularly prominent in plant cells.

- Chloroplasts: (In plant cells and algae) Organelles for photosynthesis, converting light energy into chemical energy. Like mitochondria, they have their own DNA and are believed to have originated from endosymbiosis.

Examples of Eukaryotes

Eukaryotes encompass a vast array of organisms, including:

- Animals: Multicellular organisms characterized by heterotrophic nutrition, motility, and complex organ systems.

- Plants: Multicellular organisms characterized by autotrophic nutrition (photosynthesis), cell walls made of cellulose, and specialized tissues and organs.

- Fungi: Mostly multicellular organisms characterized by heterotrophic nutrition (absorption), cell walls made of chitin, and filamentous structures (hyphae).

- Protists: A diverse group of mostly unicellular eukaryotic organisms that do not fit neatly into the other eukaryotic kingdoms. Examples include amoebas, paramecia, and algae.

- Algae: A diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotes, ranging from unicellular (e.g., diatoms) to multicellular forms (e.g., seaweed).

References

-

Cooper GM. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9841/. Accessed January 29, 2025.

-

Archibald JM. Endosymbiosis and eukaryotic cell evolution. Curr Biol. 2015;25(19):R911-R921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.055

-

Wurzbacher Carmen E., Hammer Jonathan, Haufschild Tom, Wiegand Sandra, Kallscheuer Nicolai, Jogler Christian. “Candidatus Uabimicrobium helgolandensis”—a planctomycetal bacterium with phagocytosis-like prey cell engulfment, surface-dependent motility, and cell division. mBio. 2024;15(10):e02044-24. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02044-24

-

Karlin S, Mrázek J. Compositional differences within and between eukaryotic genomes. PNAS. 1997;94(19):10227-10232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10227

-

Hinnebusch J, Tilly K. Linear plasmids and chromosomes in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10(5):917-922. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00963.x

-

Webster MW, Weixlbaumer A. The intricate relationship between transcription and translation. PNAS. 2021;118(21):e2106284118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106284118

-

Secaira-Morocho H, Chede A, Gonzalez-de-Salceda L, Garcia-Pichel F, Zhu Q. An evolutionary optimum amid moderate heritability in prokaryotic cell size. Cell Rep. 2024;43(6):114268. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114268

-

Cole LA. Biology of Life. Academic Press; 2016:93-99. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128096857000137. Accessed January 29, 2025.

-

Simon M, Plattner H. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. Academic Press; 2014:141-198. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B978012800255100003X. Accessed January 29, 2025.