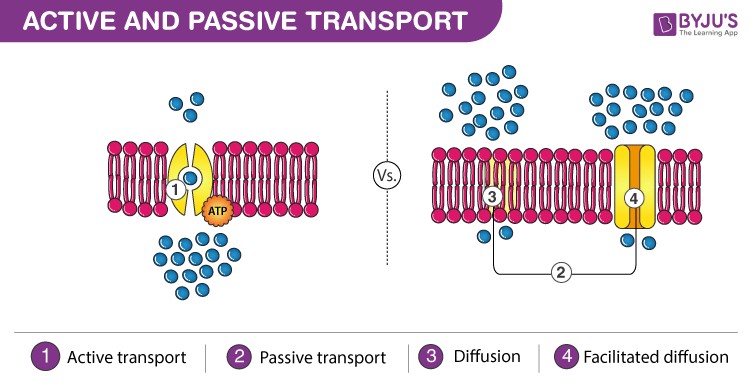

In the realm of cellular biology, the transportation of molecules across cell membranes is paramount for life. Cells must absorb nutrients, expel waste, and maintain a stable internal environment. These essential tasks are largely accomplished through two fundamental processes: active and passive transport. While both active and passive transport facilitate the movement of substances across cell membranes, they differ significantly in their energy requirements and the direction of movement relative to the concentration gradient.

“Active transport is the movement of molecules across a membrane from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration, against the concentration gradient. This process typically requires the assistance of enzymes and always necessitates cellular energy, often in the form of ATP.”

“Passive transport, in contrast, is the movement of molecules and ions across the cell membrane that does not require the cell to expend energy. This is because it relies on the inherent kinetic energy of molecules and follows the concentration gradient.”

Essentially, both active and passive transport are critical for cellular function, ensuring cells receive necessary materials and eliminate waste products. However, the mechanisms and energy demands of these two processes are distinctly different. Let’s delve into a detailed comparison to understand these differences.

Diagram comparing active and passive transport mechanisms in cells, highlighting energy requirement and concentration gradient direction for each process.

Diagram comparing active and passive transport mechanisms in cells, highlighting energy requirement and concentration gradient direction for each process.

Active Transport: Moving Against the Tide

Active transport is characterized by its requirement for cellular energy to move substances across the cell membrane. This energy, often in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), is crucial because active transport moves molecules against their concentration gradient. Imagine pushing a ball uphill – it requires energy. Similarly, active transport moves molecules from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration.

This process is vital for cells to accumulate necessary substances, even when their concentration outside the cell is lower. Active transport is highly selective and can transport a wide array of molecules, including ions, large polar molecules, and even very large particles. Key features of active transport include:

- Energy Requirement: ATP is the primary energy currency powering active transport.

- Movement Against Concentration Gradient: Substances are moved from areas of low concentration to high concentration.

- Selectivity: Often involves specific carrier proteins embedded in the cell membrane to bind and transport particular molecules.

- Directionality: Typically unidirectional, moving substances in a specific direction across the membrane.

- Temperature Sensitivity: Being enzyme-mediated, active transport is influenced by temperature changes.

- Metabolic Dependence: Processes like cellular respiration that produce ATP directly impact active transport. Metabolic inhibitors can halt active transport by disrupting energy supply.

There are two main types of active transport:

-

Primary Active Transport: Directly uses ATP to move molecules. A prime example is the sodium-potassium pump, essential for nerve cell function and maintaining cellular ion balance. This pump uses ATP to expel sodium ions from the cell and bring potassium ions into the cell, both against their concentration gradients.

-

Secondary Active Transport: Indirectly uses energy. It harnesses the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport. For instance, the sodium gradient created by the sodium-potassium pump can drive the transport of other molecules, like glucose, into the cell.

Processes like endocytosis and exocytosis are also forms of active transport, used for the bulk transport of large molecules or particles across the membrane.

- Endocytosis: The cell membrane engulfs substances from outside the cell, forming vesicles to bring them inside.

- Exocytosis: Vesicles fuse with the cell membrane to release substances outside the cell.

These processes are critical for nutrient uptake, waste removal, and cell signaling.

Passive Transport: Going with the Flow

Passive transport, in stark contrast to active transport, does not require the cell to expend any metabolic energy. It relies on the inherent kinetic energy of molecules and the principles of diffusion. Molecules in passive transport move down their concentration gradient, from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration, much like a ball rolling downhill.

This process is crucial for the efficient movement of small, nonpolar molecules, water, and certain ions across the cell membrane. Passive transport is essential for processes like gas exchange, nutrient absorption, and waste elimination. Key characteristics of passive transport are:

- No Energy Requirement: Driven by the concentration gradient and kinetic energy of molecules.

- Movement Down Concentration Gradient: Substances move from areas of high concentration to low concentration.

- Non-Selective to Partly Selective: Simple diffusion is non-selective, while facilitated diffusion involves carrier proteins and is therefore selective.

- Bidirectional Movement: Molecules can move in both directions across the membrane, but the net movement is down the concentration gradient.

- Temperature Independence (mostly): While temperature can slightly affect the rate of diffusion, it’s not a primary influencing factor like in active transport.

- Metabolic Inhibitor Independence: Passive transport is not directly affected by metabolic inhibitors as it doesn’t rely on cellular energy production.

There are several types of passive transport:

-

Simple Diffusion: Direct movement of small, nonpolar molecules (like oxygen and carbon dioxide) across the membrane. This is driven solely by the concentration gradient.

-

Osmosis: The diffusion of water across a semi-permeable membrane from an area of higher water concentration (lower solute concentration) to an area of lower water concentration (higher solute concentration). Osmosis is crucial for maintaining cell turgor pressure and water balance.

-

Facilitated Diffusion: Movement of molecules across the membrane with the help of membrane proteins. These proteins can be channel proteins (forming pores) or carrier proteins (binding and changing shape to transport molecules). Facilitated diffusion is still passive because it relies on the concentration gradient and does not require cellular energy. Glucose transport into cells is a common example of facilitated diffusion via carrier proteins.

Key Differences at a Glance

To summarize the key distinctions, consider the following table:

| Feature | Active Transport | Passive Transport |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Requirement | Requires cellular energy (ATP) | Does not require cellular energy |

| Concentration Gradient | Moves against the concentration gradient (low to high) | Moves down the concentration gradient (high to low) |

| Selectivity | Highly selective | Partly non-selective to selective (facilitated) |

| Directionality | Unidirectional | Bidirectional (net movement down gradient) |

| Speed | Can be rapid | Comparatively slower |

| Temperature Influence | Influenced by temperature | Not significantly influenced by temperature |

| Carrier Proteins | Always required | May or may not be required (facilitated diffusion) |

| Oxygen Content Level | Reduced oxygen can halt or reduce process | Not affected by oxygen levels |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Influenced and stopped by metabolic inhibitors | Not influenced by metabolic inhibitors |

| Examples | Sodium-potassium pump, endocytosis, exocytosis | Diffusion, osmosis, facilitated diffusion |

The Importance of Both Transport Mechanisms

Both active and passive transport are indispensable for cellular life. Passive transport efficiently handles the movement of essential small molecules and maintains basic cellular equilibrium. Active transport, while energy-intensive, allows cells to create and maintain internal environments different from their surroundings, accumulate vital nutrients, and expel waste against concentration gradients.

For instance, the uptake of glucose in the human intestine involves both active and passive transport. Initially, glucose absorption from the intestinal lumen into epithelial cells can occur via secondary active transport, coupled with sodium movement. Subsequently, glucose moves from epithelial cells into the bloodstream via facilitated diffusion (passive transport).

Similarly, gas exchange in the lungs (oxygen in, carbon dioxide out) relies on simple diffusion (passive transport), while nutrient uptake in plant roots often involves active transport to accumulate minerals against concentration gradients in the soil.

In conclusion, active and passive transport are complementary processes that together ensure the dynamic exchange of substances across cell membranes, vital for cell survival and function. Understanding the differences and interplay between these transport mechanisms is fundamental to comprehending cellular biology and physiology.