Introduction

The scientific community widely agrees that climate change, largely driven by human activities, is set to significantly impact human health across the globe (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2014). These health impacts range from increased instances of heat-related illnesses and deaths to shifts in disease patterns (Haines et al. 2006; McMichael et al. 2012). Both the United Kingdom and Australia are anticipating considerable increases in annual and seasonal average temperatures throughout the 21st century, although these temperature rises will vary geographically [Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) 2014; Jenkins et al. 2009]. Notably, the frequency of extremely hot days is already on the rise and is projected to escalate further (Vardoulakis and Heaviside 2012), mirroring trends observed in other parts of Europe and North America (Meehl and Tebaldi 2004).

Heat-related mortality is a significant and growing public health concern, especially as climate change intensifies (Huang et al. 2011). The effects of heat on health are expected to worsen due to rising temperatures and more frequent and intense heat waves (Fischer and Schar 2010; Nitschke et al. 2011; Tong et al. 2010). Interestingly, despite overall warming trends, climate models also suggest that extreme cold weather events will still occur, particularly in continental Europe and other mid- to high-latitude regions throughout the 21st century (Kodra et al. 2011). This complex interplay of changing weather patterns necessitates a detailed examination of both heat and cold-related health impacts.

The severity of climate change-related health consequences will differ greatly among countries and populations. Older adults, for example, are considerably more susceptible to both heat and cold compared to younger individuals (Hajat et al. 2007, 2014). Furthermore, the risks associated with temperature extremes can vary significantly within and between countries (Analitis et al. 2008; McMichael et al. 2008). By comparing the health impacts in different geographical locations with varying climates and socioeconomic conditions, we can gain valuable insights into the underlying risk factors (Gosling et al. 2009a; McMichael et al. 2008). Research indicates that cities with cooler average summer temperatures may have lower temperature thresholds for heat-related health effects compared to warmer cities (Gosling et al. 2009a). This suggests that populations may develop a degree of acclimatization and adaptation to warmer climates through physiological adjustments, spontaneous behavioral changes (like wearing lighter clothing), and planned adaptations (such as building insulation and urban green spaces) (O’Neill et al. 2009).

The extent and speed of adaptation are likely influenced by numerous location-specific factors, including the characteristics of the built environment. Many studies assessing the future health impacts of climate change have primarily focused on changes in average temperatures, often without considering how populations might adapt to these changes (Gosling et al. 2009a; Kinney et al. 2008). Currently, there is no universally accepted method to account for acclimatization and adaptation in health impact assessments (Hajat et al. 2014. Various approaches have been proposed, such as comparing “analog cities” (cities with different average temperatures but similar socioeconomic profiles) or “analog years” (the hottest years on record) to understand potential adaptation effects (Gosling et al. 2009a; Huang et al. 2011; Kinney et al. 2008).

While numerous studies have documented the link between ambient temperatures and mortality (Armstrong et al. 2011; Barnett et al. 2012; Basu 2009; Basu and Samet 2002; Gosling et al. 2009b; Hajat et al. 2007, less research has focused on the projected future impacts of climate change on temperature-related mortality (Christidis et al. 2010; Huang et al. 2011; Kinney et al. 2008). This study aims to address this gap by evaluating the direct effects of temperature exposure on public health in the United Kingdom and Australia throughout the 21st century. By modeling mortality impacts based on current weather patterns across different regions and age groups, and applying these relationships to climate and population projections, we estimate the future burden of temperature-related health issues in UK regions and major Australian cities during the 2020s, 2050s, and 2080s under various emissions scenarios. Furthermore, this study provides a systematic comparison of these health burden estimates between the two countries and across different age demographics. This comparative approach is crucial for understanding the nuances of Comparative Weather impacts on public health.

Methods

The assessment of mortality associated with temperature fluctuations was conducted in three key stages: a) time-series regression analyses of daily mortality counts and weather variables for both UK regions and Australian cities; b) evaluation of health impacts attributable to heat and cold under both current and projected climate conditions; and c) modeling the influence of demographic shifts on future mortality burdens.

Statistical Time-Series Analyses. Mortality data for England and Wales from 1993 to 2006 and for the five most populous Australian cities (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, and Perth) from 1990 to 2006 were sourced from the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), respectively. Individual death records were aggregated to create daily time series of all-cause mortality for the study periods. All-cause mortality was considered to capture the broad influence of weather on health, as temperature can contribute to deaths from various causes. Data were categorized by age group (0–64, 65–74, 75–84, ≥ 85 years) and geographic region (10 government regions of England and Wales and the 5 Australian cities).

Ambient temperature and relative humidity data were obtained from the British Atmospheric Data Centre (2014) and the Australian BoM (2014). Daily mean temperature and relative humidity series were created for each region and city, using data only from weather stations with data capture for at least 75% of the days during the study periods. Where multiple weather stations were available, population-weighted averages were used to calculate daily mean values, following the methodology of Armstrong et al. (2011).

Time-series regression analyses were performed using Stata software (version 12; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) to determine the short-term relationships between daily average temperatures and daily mortality. Poisson regression with overdispersion was assumed in all models. Heat and cold effects were analyzed separately. For heat-related mortality, models were limited to summer months (June–September in the UK and December–March in Australia). Long-term mortality trends were accounted for using linear and quadratic time terms. Seasonal patterns within the year were controlled using natural cubic splines (NCS) of time with 4 degrees of freedom (df) per summer. NCS were also used to adjust for the effects of daily relative humidity, and day-of-week effects were modeled using indicator variables. For cold-related mortality, all-year models were used to capture impacts beyond winter. Confounder control was similar to heat-related mortality models, with added seasonal control (8 df/year) and inclusion of daily influenza deaths from the UK ONS (influenza data were not available for Australia). While air pollution was not adjusted for, prior research has shown that adjusting for particulate matter ≤ 10 μm (PM10) and ozone (O3) in London had minimal impact on heat and cold-related relative risk (RR) estimates (Hajat et al. 2014). Similarly, controlling for PM10, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), or O3 in Brisbane did not alter the temperature-mortality relationship in a previous study (Huang et al. 2012).

Graphical analysis using NCSs of temperature suggested temperature thresholds for both heat and cold, beyond which mortality risk increased (graphs not shown). For quantification, the 93rd percentile (average of lags 0–1) and 60th percentile (average of lags 0–27) of the daily mean temperature distribution within each UK region or Australian city were used as heat and cold thresholds, respectively, based on prior research (Armstrong et al. 2011; Hajat et al. 2014. Sensitivity analyses using the 90th percentile (average of lags 0–1) and 65th percentile (average of lags 0–27) were also conducted. Daily mortality and temperature distributions, along with thresholds for heat and cold effects, are available in Supplemental Material, Figures S1 and S2. Heat-related deaths, occurring shortly after exposure (Basu and Samet 2002), were modeled using the average of same-day and previous-day temperatures. Cold effects, which can be delayed (Bhaskaran et al. 2010]), were modeled using temperatures averaged over 28 days.

Heat and cold effects are presented as the RR of death per 1°C increase or decrease in temperature above or below the respective threshold. RRs were estimated for each UK region and Australian city, for all ages and age groups, and country-level mean RRs were calculated using a DerSimonian and Laird random-effects meta-analysis (DerSimonian and Laird 1986).

Health Impact Assessment. Projected monthly mean temperatures for the 2020s, 2050s, and 2080s were obtained from the UK Climate Impacts Programme (UKCIP) Climate Projections (UKCP09 2009) and the Australian Climate Change Scenarios Generator (OzClim 2011). These projections are based on the Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Model (HadCM3) (Gordon et al. 2000 for the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) (Nakicenovic et al. 2000) at approximately 25 km resolution. Three SRES emissions scenarios were used: low (B1), medium (A1B), and high (A1FI).

Daily mean temperature series were generated for each emissions scenario. For each region in England and Wales, the mean monthly temperature across grid squares within the regional boundary was calculated. For Australian cities, the temperature of the most central grid square was used. The difference from the baseline period (1993–2006) average monthly temperature was then applied to the daily mean temperatures of the baseline period to create future daily temperature time series. This process yielded three daily mean temperature time series per region or city, one for each emissions scenario.

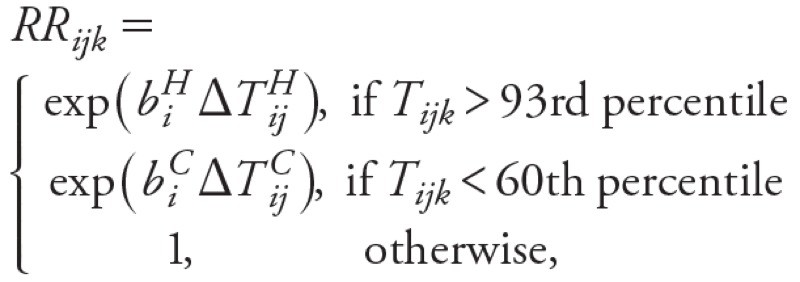

Temperature-related mortality was calculated for the baseline period (1993–2006) and the three future decades (2020s, 2050s, 2080s) for the 10 UK regions and 5 Australian cities using the following formula:

| [1] |

|---|

| [2] |

|---|

Where Mij is the estimated temperature-related deaths per year in region i during decade j, Pij is the population in region i during period j, Dik is the daily mortality rate for all-cause deaths in region i on day k, RRijk is the relative risk for heat or cold effects in region i on day k of decade j, and biH and biC are the slopes of the temperature–mortality relationship for heat (H) and cold (C) in region i. ΔTHijk and ΔTCijk represent the deviations of daily mean temperatures above or below the heat and cold thresholds. Mortality burdens were estimated for all ages and separately for age groups (0–64, 65–74, 75–84, ≥ 85 years).

Temperature-mortality relationships and daily mortality rates were kept constant over time to isolate the effect of temperature changes under different emissions scenarios.

Demographic Changes. Initial health impact assessments used 2001 census population data. Calculations were repeated using regional population projections from the 2010-based principal projections for the UK (ONS 2011) and the 2006-based mid-range (Series B) projections for Australia (ABS 2008b), aggregated into the four age groups for the three future decades. Population projections are based on assumptions about fertility, mortality, and migration, which are broadly similar between the UK and Australia (ONS (2011); ABS (2008b)).

Results

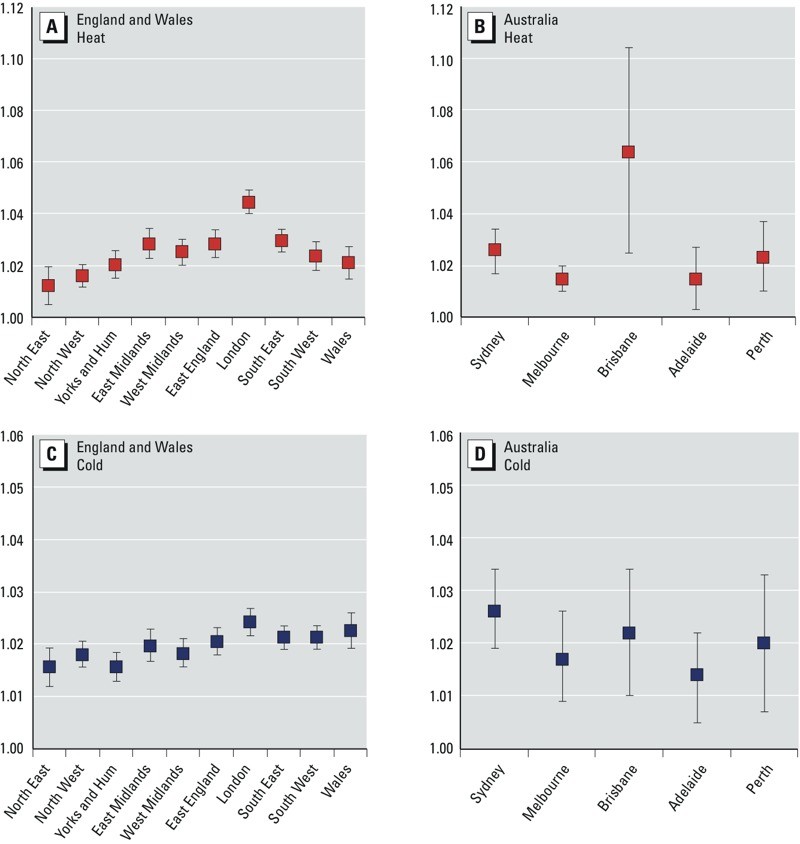

Temperature–Mortality Relationships. The study found statistically significant increases in all-cause mortality (p < 0.05) when daily mean temperatures exceeded the 93rd percentile thresholds in both UK regions and Australian cities (Figure 1). Heat-related RRs showed considerable regional variation, with London exhibiting generally higher RRs compared to other regions in England and Wales (Figure 1). Similarly, in Australia, significant heterogeneity was observed in RRs across cities, with Brisbane showing a higher RR. However, it’s important to note that confidence intervals (CIs), especially for Brisbane and other Australian cities (Adelaide and Perth), are wider due to smaller population sizes compared to Sydney, Melbourne, London, and other UK regions.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Estimated RRs and 95% CIs for all-cause mortality due to heat (A,B; temperature threshold: 93rd percentile, lags 0–1) and cold (C,D; temperature threshold: 60th percentile, lags 0–27) for all ages in the England and Wales region (left) and cities of Australia (right). Yorks and Hum, Yorkshire and Humber. The RRs were derived from time-series regression analyses assuming Poisson variation with scale overdispersion. Heat and cold effects were estimated separately.

Statistically significant positive associations were also found between all-cause mortality and daily mean temperatures below the 60th percentile threshold in both the UK and Australia (Figure 1). In the UK, the heterogeneity in estimated cold effects was less pronounced than for heat effects, although London again showed generally higher RRs for cold effects compared to other regions. Australian RR CIs were again wider.

For England and Wales, the national-level percentage increase in mortality linked to heat exposure was 2.5% (95% CI: 1.9, 3.1) per 1°C rise above the heat threshold (93rd percentile), while for cold it was 2.0% (95% CI: 1.8, 2.2) per 1°C drop below the cold threshold (60th percentile). In Australian cities, the overall percentage increase in mortality associated with heat was 2.1% (95% CI: 1.3, 2.9), and for cold it was 2.0% (95% CI: 1.5, 2.4) using the same percentile thresholds. While overall heat and cold-related RR estimates were broadly similar within and between countries based on 1993-2006 data, the higher frequency of days below the cold threshold led to a greater number of deaths attributable to cold weather (Figure 2). The overall mortality burdens for 1993–2006 were also considerably larger in the UK regions due to the significantly larger population of England and Wales compared to the five Australian cities (approximately 52 million vs. 12 million in 2001).

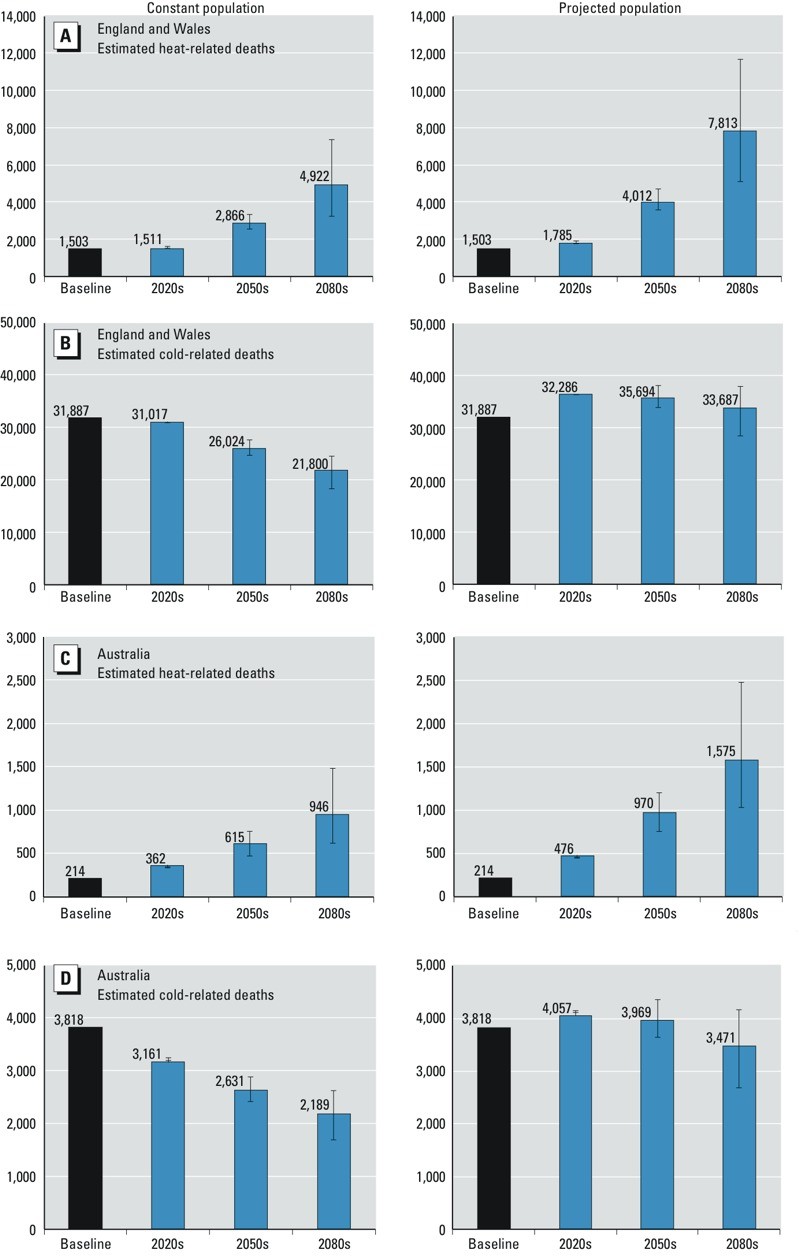

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Estimates of heat-related and cold-related deaths in England and Wales regions (A,B) and five Australian cities (C,D) per year for all ages for 2001 populations (left) and projected populations (right). The mortality estimates are based on estimated RRs for heat or cold effects in each region, the daily mortality rate for all-cause deaths and population size in each region, and regional daily mean temperatures. Blue bars show estimates based on SRES A1B; B1 and A1FI estimates are shown as error bars. Temperature thresholds: 93rd percentile for heat and 60th percentile for cold. Baseline period: 1993–2006.

Mortality RR estimates by age group for 1993–2006 generally indicated significant heat and cold-related risks across all four age groups (0–64, 65–74, 75–84, ≥ 85 years), with older age groups exhibiting greater vulnerability to temperature extremes (see Supplemental Material, Table S1). Both heat and cold-related risks increased with age in both the UK and Australia, with the highest risks observed in the ≥ 85 years age group.

Health Impacts. Figure 2 (Figure 2) presents the estimated annual mortality burdens associated with hot and cold weather in UK regions and Australian cities, based on the 93rd and 60th percentile temperature thresholds, for the baseline period (1993–2006) and future decades (2020s, 2050s, and 2080s). Results are shown for both 2001 populations and projected future populations. (See Supplemental Material, Figures S3 and S4 for results using 90th and 65th percentile thresholds).

For the UK, assuming constant 2001 regional populations, annual mean heat-related mortality is projected to increase by approximately 90% between the 2020s and 2050s (125% with population projections), and by about 72% between the 2050s and 2080s (95% with population projections) under the medium emissions scenario (A1B). Cold-related mortality is projected to decrease by roughly 16% over 2020s–2050s (2% with population projections) and another 16% over 2050s–2080s (6% with population projections) under the same scenario.

In the five Australian cities, with constant 2001 populations, annual mean heat-related mortality is projected to increase by about 70% between the 2020s and 2050s (104% with population projections), and by around 54% between the 2050s and 2080s (62% with population projections) under the A1B scenario. Cold-related mortality is projected to decrease by approximately 17% over 2020s–2050s (2% with population projections) and by another 17% over 2050s–2080s (13% with population projections) under the same scenario.

Overall, cold-related mortality is projected to remain higher than heat-related mortality in all periods studied in both the UK and Australia. However, the ratio of cold- to heat-related deaths is expected to decrease significantly, from approximately 20 to 4 between the 2020s and 2080s in the UK, and from about 9 to 2 in Australian cities, under the medium emissions scenario (A1B).

Supplemental Material, Figure S5 presents estimated annual temperature-related deaths per 100,000 people by age group. The data strongly indicates that mortality burdens from both heat and cold are significantly higher in the 75–84 and ≥ 85 years age groups in both countries. Heat-related mortality is projected to rise sharply in these older age groups (e.g., by approximately 223% and 163% between the 2020s and 2080s for those ≥ 85 years in the UK and Australia, respectively, for the A1B scenario and constant populations), while cold-related mortality is projected to decline at a slower rate (e.g., by approximately 29% and 30% for those ≥ 85 years in the UK and Australia, respectively, for the A1B scenario and constant populations) over the same period.

Estimated rates of temperature-related mortality per 100,000 people varied across UK regions and Australian cities (Table 1) (Table 1). In the UK, London, East and West Midlands, South East, and East England showed the highest rates of heat-related deaths, while Brisbane had the highest rate in Australia. For cold-related mortality in the UK, Wales, South West, South East, and East England had the highest rates, and Sydney had the highest rate in Australia. These regional patterns of heat and cold-related mortality generally persist in future decades. Mortality rates are generally lower in Australian cities compared to UK regions, with Melbourne showing the lowest rates for both heat and cold-related mortality in Australia currently.

Table 1.

Heat- and cold-related deaths (n) in England and Wales regions and Australian cities per year per 100,000 population.

| Region | Thresholda | Baselineb | 2020s | 2050s | 2080s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1B | B1 | A1FI | |||

| United Kingdom | |||||

| Heat-related deaths | |||||

| North East | 16.6 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| North West | 17.3 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 17.5 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| East Midlands | 17.8 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.6 |

| West Midlands | 17.7 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| East England | 18.5 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| London | 19.6 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.3 |

| South East | 18.3 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| South West | 17.6 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.7 |

| Wales | 17.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| All regions | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | |

| Cold-related deaths | |||||

| North East | 10.9 | 50.1 | 54.8 | 54.7 | 54.9 |

| North West | 11.9 | 60.5 | 61.9 | 61.8 | 62.0 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 11.6 | 51.3 | 53.5 | 53.4 | 53.4 |

| East Midlands | 11.8 | 62.8 | 57.9 | 57.7 | 57.6 |

| West Midlands | 11.7 | 57.7 | 54.6 | 54.5 | 54.5 |

| East England | 12.3 | 63.2 | 59.0 | 58.9 | 58.7 |

| London | 13.3 | 60.5 | 61.0 | 60.8 | 60.7 |

| South East | 12.4 | 64.1 | 59.8 | 59.7 | 59.5 |

| South West | 12.2 | 65.7 | 60.1 | 60.1 | 60.1 |

| Wales | 11.9 | 71.7 | 71.4 | 71.3 | 71.4 |

| All regions | 61.0 | 59.3 | 59.2 | 59.2 | |

| Australia | |||||

| Heat-related deaths | |||||

| Sydney | 23.8 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| Melbourne | 21.5 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Brisbane | 26.1 | 2.9 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.9 |

| Adelaide | 24.7 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Perth | 25.8 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| All cities | 1.8 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.0 | |

| Cold-related deaths | |||||

| Sydney | 18.5 | 41.8 | 34.3 | 35.2 | 34.8 |

| Melbourne | 15.2 | 23.3 | 17.6 | 18.1 | 17.9 |

| Brisbane | 22.2 | 32.2 | 29.3 | 30.0 | 29.7 |

| Adelaide | 17.3 | 29.8 | 30.0 | 30.6 | 30.3 |

| Perth | 19.7 | 30.8 | 22.9 | 23.5 | 23.2 |

| All cities | 32.5 | 26.9 | 27.6 | 27.3 |

Table 1. Heat- and cold-related deaths (n) in England and Wales regions and Australian cities per year per 100,000 population. Regional estimates of temperature-related deaths per year based on estimated RRs for heat or cold effects, the daily mortality rate for all-cause deaths and population size in each region, and projected daily mean temperatures for three SRES emission scenarios (A1B, B1, and A1FI). aTemperature thresholds (oC) correspond to the 93rd percentile for heat and 60th percentile for cold effects. bBaseline period refers to 1993–2006.

Sensitivity analyses using different temperature thresholds (90th/65th percentiles) yielded generally comparable mortality burden estimates for both the UK and Australia across all periods, with some minor differences (e.g., cold-related deaths in the UK in the 2080s) (see Supplemental Material, Figures S3, S4, S6). These variations, however, do not alter the overall interpretation of the findings, with the same regions and population groups identified as being at highest mortality risk.

Discussion

Summary of Findings. This research provides quantitative estimates of current and future temperature-related mortality burdens in the UK and Australia. These two countries, despite having broadly similar socioeconomic profiles, present contrasting climates, population densities, and infrastructure. Assuming no significant adaptation to climate change, heat-related mortality is projected to increase dramatically (e.g., by approximately 90% and 70% between the 2020s and 2050s in the UK and Australia, respectively, for constant populations) by mid-century and beyond. This increase is driven by rising average temperatures, population growth, and aging demographics. Conversely, cold-related mortality is projected to decline, but at a slower rate (e.g., by approximately 16% and 17% between the 2020s and 2050s in the UK and Australia, respectively, for constant populations), and this decrease is largely offset by population aging. Despite the projected increase in heat-related deaths, the absolute number of cold-related deaths is expected to remain higher in both UK regions and Australian cities throughout the assessment period.

Our results indicate that heat-related mortality RRs are generally lower in most major Australian cities (Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth, and Sydney) compared to London, while Brisbane’s RR is higher (though with overlapping CIs) (Figure 1). The difference in heat-related mortality RRs between London and Melbourne could be attributed to a degree of physiological acclimatization to heat in Melbourne’s population, but it may also reflect behavioral and planned adaptations, such as the use of cooling technologies, urban planning strategies, building designs, and vegetation cover (Hajat et al. 2010). These adaptation strategies could potentially be transferred to other cities and countries.

Both the UK and Australia are facing significant demographic shifts. The population of England and Wales is projected to increase from around 52 million in 2001 to approximately 81 million by the mid-2080s, and the population of the five Australian cities in this study is expected to grow from nearly 12 million to almost 18 million over the same period. A common trend in both countries is the substantial projected growth of the ≥ 85 years age group (from about 1.9% of the total population in 2001 to around 8.9% by the mid-2080s in England and Wales, and from approximately 1.3% to 6.3% in the Australian cities). Population growth and aging are projected to significantly contribute to future temperature-related mortality in both the UK (40% for heat and 37% for cold in 2050s, and 59% for heat and 55% for cold in 2080s) and Australia (58% for heat and 51% for cold in 2050s, and 66% for heat and 59% for cold in 2080s). This demographic effect is proportionally larger for heat-related mortality and more pronounced in Australian cities than in UK regions. Improving the overall health and well-being of older adults, particularly those in urban areas, along with implementing planned adaptation measures (such as temperature-health warning systems, targeted public health campaigns, and improved home insulation), could help mitigate these substantial mortality burdens (Marmot Review Team 2011).

Our UK heat-related mortality projections are broadly consistent with previous research. Hames and Vardoulakis (2012) estimated a 74% and 57% increase in annual heat-related mortality in the UK over the 2020s–2050s and 2050s–2080s, respectively, and a 24% and 26% decrease in cold-related mortality over the same periods, based on current population levels. A study by Hajat et al. (2014) projected increases of 115% and 78% in annual heat-related deaths over the 2020s–2050s and 2050s–2080s, and corresponding decreases of 6% and 10% in cold-related deaths, considering future population projections. However, methodological differences in temperature projection methods lead to quantitative variations in results across these studies. Due to the lack of daily temperature projection time series for Australia, we used monthly projections for both the UK and Australia for consistency. This approach does not account for potential changes in daily mean temperature variability from the baseline period, which is particularly relevant for heat-related health burdens. A study by Armstrong et al. (2011) showed good agreement with the baseline heat-related mortality burden estimated in our study for England and Wales. An earlier Australian study projected a roughly 15% increase in heat-related mortality by 2070 (Bambrick et al. 2008).

Adaptation to Higher Temperatures. In this study, we have estimated temperature-related mortality assuming a stationary relationship between daily deaths and mean temperature within each region or city. This approach, assuming future temperature-mortality relationships will mirror past ones, may overestimate heat-related health burdens, as populations are likely to acclimatize and adapt to rising temperatures to some extent (Gosling et al. 2009a).

The analog city approach has been used in previous studies to model adaptation effects within a country (Kalkstein and Greene 1997; Knowlton et al. 2007). While Melbourne appears to be a reasonable analog city for London based on projected temperatures and socioeconomic status (GDP per capita: US$42,700 in Greater London vs. US$37,100 in Greater Melbourne in 2005), population density differs significantly (5,200/km2 in Greater London vs. 430/km2 in Greater Melbourne in 2012). Furthermore, in Greater Melbourne, about 23% of households are single-person, 15% are apartments, and two-thirds have air conditioning for cooling (2011 data). In contrast, in Greater London, about 32% of households are single-person, 50% are apartments, and most households do not use mechanical cooling.

In Victoria, and across Australia, air conditioner usage nearly doubled between 1994 and 2008 (ABS 2008a. Air conditioning is likely to become more common in London and other UK cities. Technological advancements and environmental considerations may also promote passive cooling techniques, including building shading, insulation, green roofs, and innovative materials (Vardoulakis and Heaviside 2012). However, existing urban infrastructure limits the extent to which cities can adapt to climate change, and populations may not fully adapt to rising temperatures (Kalkstein and Greene 1997. Increasing population density and social isolation may hinder adaptation, while improvements in healthcare and housing could facilitate it.

Severe weather protection plans and warning systems are expected to partially mitigate temperature-related mortality in both the UK and Australia, though quantitative evidence of their effectiveness is still limited. Heat wave plans are in place in England and Wales (Public Health England 2014) and in some Australian states (State of Victoria Department of Health 2011). Long-term adaptation strategies, including sustainable urban planning, climate-resilient infrastructure, effective emergency management, community engagement, and public health education, are also crucial for reducing vulnerability to severe weather (Hames and Vardoulakis 2012).

Methodological Considerations. This study utilized regional and city-level daily mortality and temperature data over a relatively long baseline period (14–17 years), projected temperatures for three future decades based on three climate scenarios, and analyzed four age groups reflecting current and future demographics. Consistent methods and models were applied to both the UK and Australia, enabling a meaningful comparison of results.

Temperature-related mortality was calculated based on a uniform monthly increase in daily mean temperatures, which does not account for potential increases in heat wave frequency, projected for temperate zones this century (Meehl and Tebaldi 2004). Hames and Vardoulakis (2012) found 18–33% higher heat-related mortality estimates for the 21st century when accounting for increased heat wave frequency using a 4-year baseline period that included major heat wave years (2003 and 2006), compared to a longer baseline period (1993–2006).

Uncertainty in our results is presented based on the three climate scenarios used. However, a comprehensive uncertainty analysis including climate model physics and population projections was not conducted. Hajat et al. (2014) showed that uncertainty related to climate model physics was substantially larger than uncertainty from different emissions scenarios.

The definition of temperature thresholds is also important. We used the 93rd and 60th percentiles of daily mean temperatures as thresholds for heat and cold effects, respectively, and tested more conservative thresholds (90th and 65th percentiles) in sensitivity analyses. Heat effect thresholds in other UK studies are typically above the 90th percentile, while cold effect thresholds are less well-defined (Armstrong et al. 2011; Donaldson et al. 2002; Hajat et al. 2007, 2014; Pattenden et al. 2003). Hames and Vardoulakis (2012) demonstrated a wide range of projected cold-related mortality estimates using different temperature percentile thresholds. Furthermore, some temperature-related mortality may be due to short-term mortality displacement (“harvesting”) (Hajat et al. 2005). While this may explain some heat-related deaths, it is less clear for cold-related deaths (Braga et al. 2002).

Finally, we did not model the additional impact of heat waves separately from the general temperature effect, as heat waves contribute to a relatively small fraction of the total current heat burden (Hajat et al. 2006).

Conclusions

Comparing temperature-related mortality estimates across different studies is challenging due to variations in methodologies. This study addressed this by using consistent methods to assess heat and cold-related mortality in the UK and Australia under three climate change scenarios.

Both countries face significant temperature-related mortality burdens, with cold-related deaths currently exceeding heat-related deaths. Older adults are most vulnerable in both countries. London showed higher vulnerability to both heat and cold compared to other UK regions, while Melbourne appeared better protected from heat. These regional differences likely reflect variations in demographic, health, behavioral, urban, and built-environment factors. Climate change is projected to lead to a substantial increase in heat-related mortality and a smaller decrease in cold-related mortality in both countries. However, cold-related deaths are expected to remain more numerous, highlighting the ongoing need for interventions to reduce cold-related mortality while emphasizing the growing urgency of protecting public health from heat. Aging populations will amplify these temperature-related health burdens.

This study indicates that percentile temperature thresholds for heat and cold effects are consistent across countries with different temperature regimes but similar socioeconomic characteristics. Differences in RR estimates between regions can inform effective adaptation strategies. Further research is needed to better understand the health effects of heat and cold, considering population acclimatization and adaptation, to support evidence-based climate change adaptation planning.

Supplemental Material

(629 KB) PDF

Click here for additional data file. (633.6KB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A.G. Capon and B.G. Armstrong for their fruitful discussion on our methods.

Footnotes

We acknowledge Public Health England’s Global Health Fund for funding this international strategic secondment at the Australian National University. We also acknowledge the support of Healthy-Polis: International Consortium for Urban Environmental Health and Sustainability.

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(629 KB) PDF

Click here for additional data file. (633.6KB, pdf)