1. Overview

Wheat stands as the most globally cultivated cereal grain, holding a paramount position in worldwide agriculture [1-4]. It serves as a primary food source for 36% of the global population and is cultivated across 70% of the world’s agricultural lands [5, 6]. On a global scale, wheat provides roughly 55% of the total carbohydrates and 21% of the food calories consumed [6-8]. Outpacing all other single grain crops, including rice and maize, in both production volume and acreage, wheat thrives in a diverse array of climates [9], making it the most critical grain crop on the planet (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of Triticum aestivum [10].

| Kingdom | Plantae (Plants) |

|---|---|

| Sub-kingdom | Tracheobionta (Vascular plants) |

| Super division | Spermatophyta (Seed plants) |

| Division | Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants) |

| Class | Liliopsida (Monocotyledon) |

| Subclass | Commelinidae |

| Order | Cyperales |

| Family | Poaceae/Gramineae (grass family) |

| Genus | Triticum (wheat) |

| Species | Triticum aestivum (common wheat) |

Wheat’s prominence among cereals stems primarily from its grains, which are rich in proteins possessing unique physical and chemical characteristics. Beyond protein, wheat also contains essential minerals like copper (Cu), magnesium (Mg), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and phosphorus (P), alongside vitamins including riboflavin, thiamine, niacin, and alpha-tocopherol. It is also a significant source of carbohydrates [11]. However, wheat proteins are known to be deficient in certain essential amino acids, notably lysine and threonine [12-14].

Enhancing wheat production and quality relies on developing new and improved wheat varieties. These varieties need to deliver higher yields and demonstrate resilience under diverse agro-climatic stresses and conditions [15]. A broad consensus exists within the plant breeding community that genetic diversity within breeding material is a cornerstone of successful crop improvement [16, 17].

1.1. Wheat Background

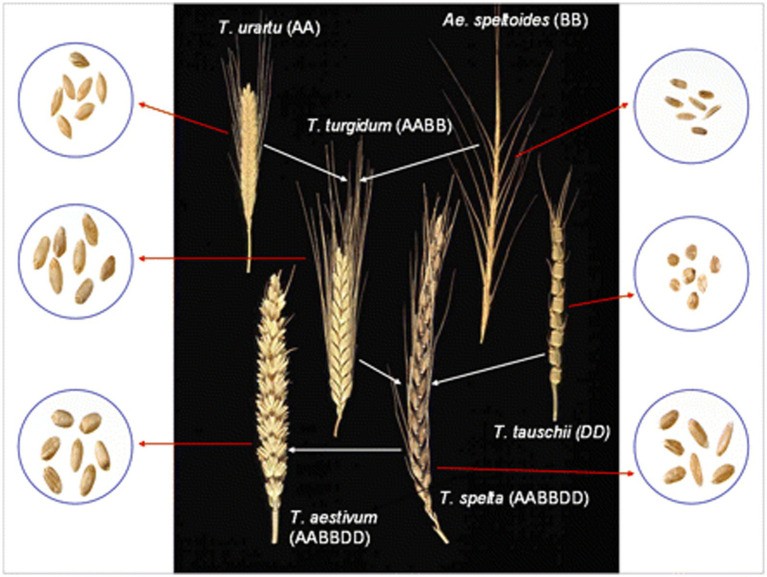

Wheat cultivation began approximately ten thousand years ago during the Neolithic Revolution, marking a pivotal shift from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to settled agriculture. Diploid einkorn wheat (genome AA) and tetraploid emmer wheat (genome AABB) were among the earliest wheat types cultivated. Genetic evidence suggests their origin in southeastern Turkey [18, 19]. Wheat cultivation expanded into the Near East around nine thousand years ago, coinciding with the first appearance of hexaploid wheat [20, 21]. Figure 1 illustrates the evolutionary and genomic relationships between cultivated bread wheat, durum wheat, and their wild diploid grass relatives, showcasing examples of spikes and grains [20].

Figure 1.

Evolutionary and genome relationships between cultivated bread and durum wheat and related wild diploid grasses, showing examples of spikes and grain.

Early wheat forms were essentially landraces derived from wild populations, selected by farmers for traits like higher yield. Domestication led to genetic trait selection in wheat, differentiating it from its wild ancestors. Two key characteristics stand out. First, spike-shattering at maturity, beneficial for seed dispersal in wild populations [22], is undesirable in cultivated wheat as it leads to harvest loss. Second, the non-shattering characteristic, resulting from mutations at the brittle rachis (Br) locus [23], and the shift from husked to free-threshing forms, where the outer husk is easily removed from the grain. Free-threshing forms arose from a mutation at the Q locus, modifying the effect of recessive mutations at the tenacious grain husk (Tg) locus [18, 24, 25].

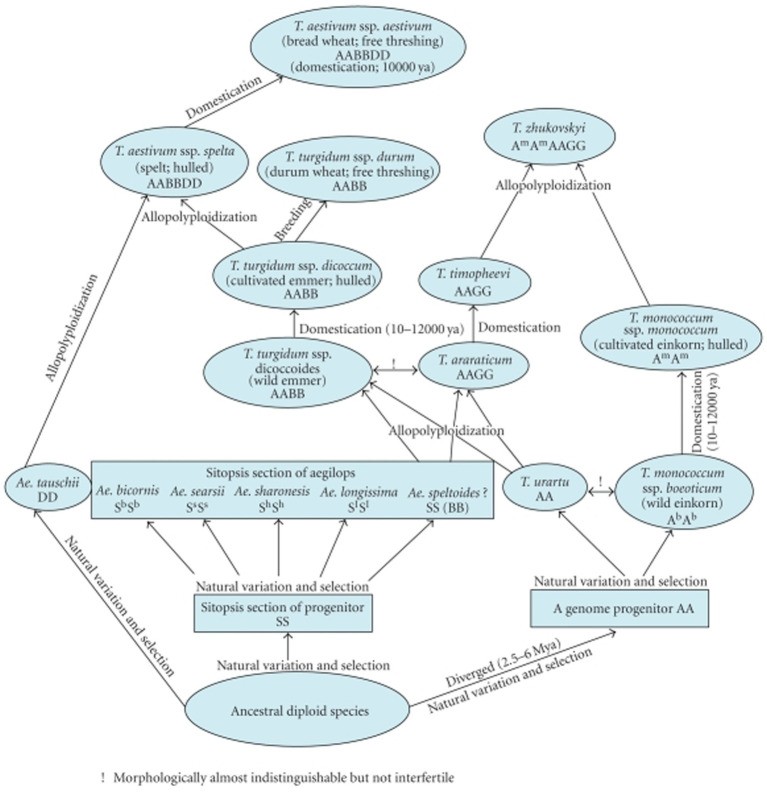

The haploid DNA content of hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L. em Thell, 2n = 42, AABBDD) is approximately 1.7 × 1010 base pairs. This is significantly larger than the genome of Arabidopsis (100x), rice (40x), and maize (nearly 6x) [20, 26]. A substantial portion of bread wheat’s DNA sequence originates from polyploidy and subsequent duplication, with repetitive DNA sequences accounting for about 80% of the entire genome [27, 28]. A typical wheat chromosome is approximately 810 MB, 25 times larger than a typical rice chromosome. Figure 2 illustrates the evolutionary history of wheat [29].

Figure 2.

Evolutionary history of wheat.

Currently, hexaploid bread wheat constitutes about 95% of global wheat cultivation, with tetraploid durum wheat making up the remaining 5% [21]. Durum wheat is better suited to arid Mediterranean climates than bread wheat and is primarily used for pasta production [30]. Minor quantities of other wheat species, such as emmer, spelt, and einkorn, are cultivated in regions like the Balkans, Spain, Turkey, and the Indian subcontinent [20, 31].

1.2. Taxonomic Classification

Refer to Table 1 for the taxonomic classification of Triticum aestivum.

1.3. Types of Wheat

The genus name Triticum originates from the Latin word ‘tero’, meaning ‘I thresh.’ The modern scientific name, Triticum aestivum, specifically refers to hexaploid bread wheat with A, B, and D genomes. This distinguishes it from tetraploid macaroni wheat, Triticum durum, which possesses A and B genomes and is primarily used for pasta. Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) is the most widely cultivated type today. It is a free-threshing hexaploid wheat (genome AABBDD). According to Nesbitt and Samuel, bread wheat arose from a relatively recent hybridization event between diploid Aegilops tauschii var. strangulate (DD genome) and an allotetraploid wheat (AABB genome) approximately 8,000 years ago [32].

Both Triticum aestivum and Triticum durum have seven pairs of chromosomes (2n = 14). Wheat is cultivated in both spring and winter forms. In very cold climates, spring wheat varieties are planted in spring, allowing them to grow and mature quickly before autumn snowfall. In more temperate regions, winter wheat is sown before winter. Winter wheat requires a period of cold (vernalization) for proper development, enabling rapid growth when snow melts in spring. In warmer climates, the distinction between spring and winter wheat is less critical. The primary difference in these environments is the timing of maturity – early or late [33]. Wheat types are often differentiated by endosperm texture, seed coat color, dough strength, grain color, and planting season. These characteristics are briefly described below [34].

1.3.1. White and Red Wheat

Red wheat varieties generally exhibit greater dormancy than white wheat varieties. This makes them preferable in environments where pre-harvest sprouting is a concern. White wheat varieties are better suited to regions that are dry during ripening and harvest, and are favored for producing flatbreads and noodles [35].

1.3.2. Soft and Hard Wheat

Despite the numerous wheat varieties grown worldwide, they broadly fall into two main categories (Table 2) with distinct properties: hard wheat and soft wheat [37]. The hardness or softness of wheat relates to its resistance to milling and the starch damage during milling [35].

Table 2.

Principal cultivars of soft and hard wheat cultivated globally [36].

| Hard wheat varieties | Description