Introduction

The rise of online education has revolutionized access to learning, offering flexibility and convenience to students worldwide. Challenging the long-established traditional classroom model, online learning platforms have become increasingly sophisticated, prompting educational institutions to critically evaluate their teaching methodologies. This Comparative Research Study delves into the effectiveness of online versus traditional face-to-face (F2F) instruction over an eight-year period. Analyzing the academic performance of 548 students enrolled in an environmental science course—401 in traditional settings and 147 online—this research aims to determine which instructional approach yields superior student outcomes. Beyond the overarching comparison, this study also investigates score variations across genders and academic classifications to identify if the teaching modality has a differential impact on specific student demographics. Our findings reveal no significant difference in overall student performance between online and F2F learning environments, irrespective of gender or academic standing. These results suggest that environmental science concepts, tailored for non-STEM majors, can be effectively conveyed through both online and traditional platforms with comparable success, highlighting the potential of online learning to broaden participation in citizen science.

The advent of internet-based education has democratized access to quality education for individuals constrained by geographical limitations and rigid schedules. Web-based learning platforms extend educational opportunities globally, requiring only an internet connection. While online education offers numerous advantages over traditional methods, such as increased accessibility and flexibility, it also presents challenges, including potentially diminished opportunities for in-person interaction and community building. Despite these drawbacks, online learning is increasingly becoming the preferred mode of education for many seeking higher education degrees.

This comparative research study focuses on evaluating the efficacy of online versus traditional F2F instruction within the context of an environmental science curriculum. Using student performance as the primary metric, we sought to ascertain whether the instructional medium significantly influences academic outcomes. This investigation compares online and F2F teaching across three dimensions: instructional modality itself, gender, and academic class rank. Through these focused comparisons, we aimed to identify if one teaching approach demonstrates a statistically significant advantage over the other. Acknowledging the inherent limitations of this study, its primary objective is to contribute valuable insights into the ongoing debate regarding the relative effectiveness of online and traditional learning environments, building upon previous research in this area Mozes-Carmel and Gold, 2009. The methodologies and analytical tools employed in this comparative analysis can be further developed and applied in future research, encompassing quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods approaches, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of this topic. Furthermore, the findings of this study can serve as a foundational element for broader meta-analyses in the field of educational modality comparison.

The Evolution of Online Education: A Historical Perspective

Computer-assisted learning is reshaping the educational landscape, with a growing number of students choosing online education for its accessibility and flexibility. Higher education institutions are increasingly recognizing the efficiencies offered by web-based education and are rapidly expanding their online course offerings to cater to a global student body. Research indicates a substantial surge in online course availability, with universities dramatically increasing their online programs in recent years Lundberg et al., 2008. Think tanks and educational organizations are also reporting significant growth in online student enrollment. For instance, the Sloan Consortium reported a 17% increase in online student numbers in 2010, surpassing the 12% growth rate of the preceding year Keramidas, 2012.

Contrary to popular perception, online education is not a modern invention. Distance learning and correspondence courses emerged in the mid-1800s, pioneered by the University of London. This early model relied heavily on postal services and reached America later in the nineteenth century. In 1873, the “Society to Encourage Home Studies” in Boston, Massachusetts, is recognized as the first formal correspondence education program in the United States. Since then, non-traditional learning has evolved into the robust online education system we know today. Technological advancements have undeniably accelerated the accessibility and speed of distance learning, enabling students worldwide to participate in courses from their homes.

Key Characteristics: Online vs. Traditional Face-to-Face Education

Both online and traditional F2F education share core elements. In both modalities, students are expected to engage with course material, attend classes (physically or virtually), submit assignments, and participate in collaborative projects. Similarly, educators in both settings are responsible for curriculum design, optimizing instructional quality, addressing student inquiries, fostering student motivation, and evaluating student work. Despite these fundamental commonalities, significant distinctions exist between the two educational approaches. Traditional classroom instruction is often characterized as teacher-centered, promoting passive learning, whereas online instruction is typically student-centered, encouraging active learning methodologies.

In teacher-centered, or passive learning environments, instructors typically manage classroom dynamics. The instructor delivers lectures and provides explanations, while students primarily listen, take notes, and pose questions. Conversely, in student-centered, or active learning environments, students take a more proactive role in shaping classroom dynamics. They independently analyze information, formulate questions, and seek clarification from the instructor. In this model, the teacher’s role shifts to listening, guiding, and responding to student-driven inquiries Salcedo, 2010.

Educational innovation inevitably raises questions about effectiveness. Despite the growing popularity and acceptance of online education, researchers continue to investigate its efficacy. The effectiveness of computer-assisted teaching is under ongoing scrutiny, with cost-benefit analyses, student experiences, and academic performance being rigorously assessed to determine if online education is a viable and equivalent alternative to traditional classroom instruction. This critical evaluation is expected to persist as technology advances and student expectations for enhanced learning experiences evolve.

Current research literature on the effectiveness of online courses presents a mixed and expansive landscape Driscoll et al., 2012. Some studies advocate for traditional classroom instruction, suggesting that online learners may be more prone to attrition and that online environments may lack sufficient feedback mechanisms for both students and instructors Atchley et al., 2013. These potential shortcomings can negatively impact student retention, satisfaction, and overall performance. However, proponents of distance learning argue that online education can produce student outcomes comparable to, or even exceeding, those achieved in traditional classrooms Westhuis et al., 2006.

A thorough examination of the advantages and disadvantages of both instructional modalities is essential to definitively determine which approach fosters superior student performance. While both methods have demonstrated relative effectiveness, the crucial question remains: is one demonstrably better than the other? Comparative research studies are vital to address this question and inform evidence-based decisions in educational practice.

The Growing Demand for Online Education: Meeting Student Needs

Driven by technological progress, modern learners increasingly seek high-quality educational programs that are accessible anytime, anywhere. This demand has propelled online education into a compelling option for working professionals, stay-at-home parents, and individuals with similar constraints. Beyond flexibility and accessibility, online learning offers a range of attractive benefits, including diverse program choices and enhanced time efficiency, further boosting its appeal Wladis et al., 2015.

Firstly, prospective students prioritize the ability to obtain a quality education without sacrificing work, family commitments, or incurring significant travel expenses. Online education liberates students from the constraints of fixed locations and schedules, enabling them to interact with instructors, collaborate with peers, access learning materials, and complete assignments from any location with internet access Richardson and Swan, 2003. This enhanced flexibility provides students with greater autonomy and makes the educational process more appealing. According to Lundberg et al. (2008) Lundberg et al., 2008, students may prefer online courses or fully online degree programs due to the flexible study hours they offer. For instance, working students can attend virtual classes and review recorded lectures after work hours, integrating education seamlessly into their busy lives.

Furthermore, increased study time facilitated by online learning can potentially lead to improved academic performance—more in-depth reading, higher quality assignments, and greater engagement in group projects. While research directly linking study time and performance is limited, it is often assumed that online students can leverage their schedule flexibility to dedicate more time to coursework, ultimately improving their grades Bigelow, 2009. The correlation between flexibility and student performance, particularly as measured by grades—the primary performance indicator in this study—is a significant consideration.

Secondly, online education expands program choices significantly. Traditional classroom-based learning often restricts students to institutions within commuting distance or necessitates relocation. In contrast, web-based instruction provides electronic access to a multitude of universities and diverse course offerings worldwide Salcedo, 2010. Students previously limited to local options can now access a global array of educational opportunities from a single, convenient location.

Thirdly, online environments can empower students who are typically hesitant to participate in traditional classroom settings to voice their opinions and engage in discussions. Removed from the immediate social pressures of a physical classroom, quieter students may feel more comfortable contributing to class dialogues without fear of judgment or unwanted attention. This increased participation can, in turn, potentially elevate overall class performance Driscoll et al., 2012.

Advantages of Face-to-Face Education: The Traditional Classroom Model

Traditional classroom instruction remains a well-established and refined educational method, with centuries of accumulated pedagogical experience. Face-to-face (F2F) learning offers distinct advantages that are not readily replicated in online environments Xu and Jaggars, 2016.

Firstly, and perhaps most importantly, classroom instruction is inherently dynamic. The F2F setting fosters real-time interaction, facilitating spontaneous questions and immediate feedback. It allows for flexible content delivery and enables instructors to adapt their teaching in response to immediate student needs and understanding. Online instruction can sometimes hinder this dynamic learning process, as student questions are often submitted in text form, requiring instructors and peers to respond asynchronously Salcedo, 2010. While online learning technologies are continually evolving to enhance real-time interaction, F2F instruction currently provides a level of dynamic engagement that is difficult to fully replicate online Kemp and Grieve, 2014.

Secondly, traditional classroom learning is a familiar and trusted modality for many students. Some learners may resist change and view online instruction with skepticism. These students might be less comfortable with technology or prefer the structured environment of a classroom. They may value direct personal interaction, pre- and post-class discussions, collaborative learning with peers, and the development of student-teacher relationships Roval and Jordan, 2004. They might perceive the internet as a barrier to effective learning. Discomfort with the instructional medium can negatively impact student engagement, potentially leading to decreased grades and diminished interest in the subject matter. While students can adapt to online education over time, and universities are increasingly incorporating web-based learning, a segment of the student population will continue to prefer the personal and communal aspects of classroom learning.

Thirdly, F2F instruction is not dependent on network infrastructure. Online learning relies entirely on consistent and reliable internet access. Technical issues, such as internet outages or connectivity problems, can disrupt online students’ ability to communicate, submit assignments, or access crucial learning materials. These technical disruptions can lead to frustration, hinder academic progress, and negatively impact the learning experience.

Fourthly, campus-based education provides students with access to accredited faculty and extensive research libraries. Students benefit from academic advising, faculty mentorship, and support services. Library resources, including librarians and physical collections, offer invaluable assistance with research, writing, and study skills development. Research libraries may contain resources that are not readily available online. Overall, the traditional campus environment provides students with a comprehensive ecosystem of support tools designed to enhance academic performance.

Fifthly, traditional classroom degrees often hold a perceived advantage over online degrees in the job market. Some employers and professional organizations may not view online degrees as equivalent to campus-based degrees Columbaro and Monaghan, 2009. Concerns about the rigor of online programs, including curriculum quality, exam supervision, and homework assignment standards, can contribute to this perception.

Finally, research suggests that online students may be more likely to withdraw from a course if they are dissatisfied with the instructor, the course format, or the feedback provided. Working independently and relying heavily on self-motivation and self-direction, online learners may be more inclined to drop out if they do not experience immediate positive results.

The classroom setting offers inherent motivational and support structures. Even if a student considers dropping out early in a course, the presence of instructors and peers can provide encouragement and deter withdrawal. F2F instructors can also adapt their teaching methods and course structure in real-time to improve student retention Kemp and Grieve, 2014. In contrast, online instructors are limited to electronic communication and may miss non-verbal cues that signal student disengagement or difficulty.

Both F2F and online teaching modalities possess distinct advantages and disadvantages. Further comparative research, focusing on specific learning outcomes and diverse learner populations, is needed to inform evidence-based decisions about instructional modality selection. This study examines these two modalities over an eight-year period, analyzing performance across three key dimensions, leading to the following research questions:

RQ1: Is there a statistically significant difference in academic performance between students in online and F2F sections of an environmental science course?

RQ2: Are there gender-based differences in academic performance between online and F2F students in an environmental science course?

RQ3: Is there a statistically significant difference in academic performance between online and F2F students in an environmental science course when considering academic class rank?

The findings of this study are intended to provide valuable insights for educators, administrators, and policymakers in determining the most effective instructional modalities for diverse student populations and learning contexts.

Methodology

Participants

The study population comprised 548 students from Fort Valley State University (FVSU) who completed an Environmental Science course between 2009 and 2016. The primary metric for comparing the effectiveness of online and F2F instruction was the students’ final course grades. Of the total participants, 147 were enrolled in online sections, and 401 were in traditional F2F sections. This sample size disparity is acknowledged as a limitation of the study. The student demographic included 246 males and 302 females, representing all four academic class ranks: 187 freshmen, 184 sophomores, 76 juniors, and 101 seniors. The study employed a convenience, non-probability sampling method, with the composition of the study group determined by course enrollment patterns. No specific preferences or weighting were applied based on gender or class rank; each student was treated as an individual data point.

All course sections were taught by the same full-time biology professor at FVSU, an experienced instructor with over ten years of teaching experience in both online and F2F modalities. The professor was recognized as a highly effective and tenured instructor with strong communication and classroom management skills.

The F2F course sections met twice weekly on campus, with each session lasting 1 hour and 15 minutes. The online course covered the same curriculum content as the F2F sections but was delivered entirely online using the Desire to Learn (D2L) e-learning platform. Online students were expected to dedicate equivalent study time to their F2F counterparts; however, no specific measures were implemented to track online study time. The professor employed a blend of textbook readings, lectures, class discussions, collaborative projects, and assessments to engage students in the learning process across both modalities.

This study did not differentiate between part-time and full-time students, potentially including part-time students in the analysis. Similarly, the study did not distinguish between students primarily enrolled at FVSU and those using FVSU as an auxiliary institution to fulfill course requirements.

Test Instruments

Student performance in this study was operationalized using final course grades. These grades were a composite of scores from tests, homework assignments, class participation, and a research project. These assessment components were deemed valid and relevant for evaluating student learning and providing objective performance measurements. Numerical final grades were converted to standard GPA letter grades for analysis.

Data Collection Procedures

The dataset of 548 student grades was obtained from FVSU’s Office of Institutional Research Planning and Effectiveness (OIRPE). The OIRPE provided the data to the instructor under the condition of maintaining confidentiality and restricting disclosure to third parties. Upon receiving the data, the instructor utilized SPSS software to analyze and process the data, calculating relevant statistical values. These processed values were subsequently used to draw conclusions and test the study hypotheses.

Results

Summary of Key Findings: Statistical analysis, using chi-square and independent sample t-tests, revealed no statistically significant difference in student performance between online and F2F learners [χ2 (4, N = 548) = 6.531, p > 0.05]. Similarly, no significant gender-based performance differences were found between online and F2F learners [t(145) = 1.42, p = 0.122]. Two-way ANOVA analysis also indicated no significant difference in student performance between online and F2F learners when considering academic class rank Girard et al., 2016.

The primary research question (RQ1) aimed to determine if a statistically significant difference existed in academic performance between online and F2F students.

Research Question 1

The first research question investigated whether the instructional modality (F2F vs. online) had a significant impact on student performance.

To address RQ1, a chi-square analysis was conducted to analyze the data. The chi-square test is particularly appropriate for this type of comparative research study as it allows us to assess if the observed relationship between teaching modality and student performance in our sample can be generalized to a broader population. This statistical method provides a numerical output that helps determine if the performance differences between the two groups are statistically significant.

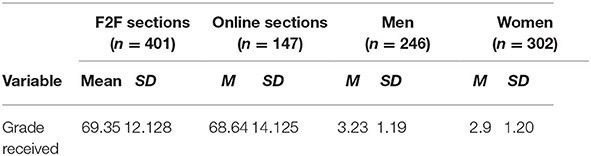

Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation (SD) of GPA scores for both instructional modalities and genders. This descriptive data provides a visual representation of score distributions and variations. The mean GPA scores for F2F learners (69.35) and online learners (68.64) are notably similar, with comparable standard deviations. A more pronounced difference is observed in GPA scores between genders, with men exhibiting a higher mean GPA (3.23) compared to women (2.9). The standard deviations for both gender groups are nearly identical. Although the numerical difference of 0.33 might appear small, within the grading scale of A to F, a 0.33 difference can be considered practically significant, representing approximately a grade increment from a B to a B+.

TABLE 1

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for 8 semester- “Environmental Science data set.”

The mean grade for men in environmental science classes (M = 3.23, N = 246, SD = 1.19) was higher than the mean grade for women (M = 2.9, N = 302, SD = 1.20) (see Table 1).

Initially, a chi-square analysis using SPSS was performed to determine if there was a statistically significant difference in grade distributions between online and F2F students. Students in the F2F class achieved the highest percentage of A grades (63.60%) compared to online students (36.40%). Table 2 illustrates the grade distribution across course delivery modalities. The chi-square test results indicated no statistically significant difference in student performance based on modality, χ2 (4, N = 548) = 6.531, p > 0.05. Table 3 presents the gender-based performance differences between online and F2F students.

TABLE 2

Table 2. Contingency table for student’s academic performance (N = 548).

TABLE 3

Table 3. Gender *performance crosstabulation.

Table 2 displays student performance metrics for online and F2F students, categorized by letter grades. F2F students show higher absolute numbers across all grade categories. However, this discrepancy is primarily due to the larger sample size of F2F students (401) compared to online students (147). When examining grade distributions as percentages within each modality, the performance differences are less pronounced Tanyel and Griffin, 2014. For example, F2F learners earned 28 A grades (63.60% of all A’s), while online learners earned 16 A grades (36.40% of all A’s). However, when considering A grades as a proportion of total students within each modality, 28 out of 401 F2F students (6.9%) achieved A’s, compared to 16 out of 147 online students (10.9%). In this proportional comparison, online learners demonstrate a slightly higher rate of A grades. This latter percentage-based measure provides a more accurate representation of relative performance levels between the two modalities.

With a critical chi-square value of 7.7 and degrees of freedom (df) of 4, the calculated chi-square statistic was 6.531. The corresponding p-value of 0.163, exceeding the significance level of 0.05, leads to the acceptance of the null hypothesis and rejection of the alternative hypothesis. Therefore, based on this analysis, there is no statistically significant difference in academic performance between online and F2F students in this environmental science course.

Research Question 2

The second research question (RQ2) explored whether the academic performance of online and F2F students varied based on gender. Specifically, does teaching modality interact with gender to influence student outcomes? Table 3 presents the gender-based performance breakdown for online and F2F students. A chi-square test was used to assess for statistically significant differences in performance between genders within each modality, using an alpha level of 0.05. The chi-square test results indicated no statistically significant gender differences in student performance in either online or F2F learning environments.

Research Question 3

The third research question (RQ3) investigated whether student performance in online and F2F modalities differed based on academic class rank. Does class rank moderate the effectiveness of online versus F2F instruction?

Table 4 presents the mean scores and standard deviations for freshmen, sophomore, junior, and senior students in both online and F2F modalities. To test RQ3, a two-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) was employed. ANOVA is a suitable statistical tool for this hypothesis as it allows for comparing means across multiple groups. Rather than focusing on specific pairwise differences, ANOVA provides a broader assessment of overall average differences. As shown in Table 4 and Table 5, the ANOVA test results indicated no statistically significant interaction effect between teaching modality and class rank on student performance. Therefore, we accept the null hypothesis and reject the alternative hypothesis, concluding that there is no significant difference in performance between online and F2F learners when considering academic class rank.

TABLE 4

Table 4. Descriptive analysis of student performance by class rankings gender.

TABLE 5

Table 5. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for online and F2F of class rankings.

As evidenced in Table 4 and Table 5, the ANOVA results indicate no significant difference in performance between online and F2F students when considering class rank. Consequently, we accept the null hypothesis and reject the alternative hypothesis.

Discussion and Social Implications

The findings of this comparative research study demonstrate that, for a non-STEM environmental science concepts course, there is no statistically significant difference in student performance between online and traditional classroom (F2F) students, regardless of instructional modality, gender, or academic class rank. Despite limitations related to sample size and study design, this assessment suggests that both online and F2F learning environments can achieve comparable student outcomes. This implies that instructional modality may be less critical than other factors in determining student success in this context. Given the limited research specifically comparing pedagogical modalities for non-STEM student populations across multiple demographic factors, this study contributes valuable and innovative insights. Existing literature often compares online and F2F learning across various dimensions (e.g., specific courses, costs, qualitative aspects), but rarely examines learning outcomes for non-STEM majors in science concepts courses over extended periods, considering modality, gender, and class rank concurrently Liu, 2005.

A study evaluating the online adaptation of a graduate-level teacher education course assessed both academic quality and learning outcomes. This research highlighted the effectiveness of online platforms in delivering course content, with students in the online course achieving learning outcomes comparable to their F2F counterparts, while also realizing cost savings for the university Herman and Banister, 2007.

Another study compared F2F and online learning in a non-STEM course, “Foundations of American Education,” examining overall student satisfaction in both modalities. While quantitative feedback indicated lower satisfaction in online courses compared to F2F, qualitative data revealed similar levels of course satisfaction across both modalities Werhner, 2010. This satisfaction data informed recommendations for enhancing online learning effectiveness in this specific course. The researchers concluded that student learning success was comparable in both online and F2F formats, emphasizing that “in terms of learning, students who apply themselves diligently should be successful in either format” Dell et al., 2010. This conclusion assumes manageable class sizes and instructor workload, acknowledging that online courses often demand more instructor effort than F2F courses Stern, 2004.

In a meta-analysis of interaction treatments in distance education, Bernard et al. (2009) Bernard et al., 2009 examined the impact of student-student (SS), student-teacher (ST), and student-content (SC) interactions in distance education (DE) courses. Their findings indicated a strong positive association between incorporating these interaction treatments into DE courses and student achievement, compared to blended or F2F learning environments. The authors suggest that these interaction treatments enhance cognitive engagement, contributing to improved learning outcomes Larson and Sung, 2009.

Other studies exploring student preferences (though not necessarily efficacy) for online versus F2F learning reveal that student preference for online learning depends on factors such as course topic and online platform technology Ary and Brune, 2011. F2F learning was often preferred for courses scheduled during late morning or early afternoon, 2-3 days per week. However, a significant preference for online learning emerged across most undergraduate course topics (including American history, humanities, natural sciences, social sciences, and international dimensions), except for English composition and oral communication. While students expressed a preference for analytical and quantitative courses online, these results were not statistically significant Mann and Henneberry, 2014. This research study, examining three hypotheses comparing online and F2F learning, accepted the null hypothesis in each case. Therefore, across all levels of analysis, no significant performance difference was found between online and F2F learners in this environmental science context. This finding carries significant implications, suggesting that traditional teaching methods, with their emphasis on interpersonal classroom dynamics, might be effectively replaced by online instruction in certain contexts. According to Daymont and Blau (2008) Daymont and Blau, 2008, online learners, irrespective of gender or class rank, learn as effectively through electronic interaction as they do through personal interaction. Similarly, Kemp and Grieve (2014) Kemp and Grieve, 2014 found comparable academic performance for psychology students in both online and F2F learning environments. Given the cost efficiencies and flexibility of online education, web-based instructional systems are likely to continue their rapid expansion in higher education.

Numerous studies support the economic advantages of online learning compared to F2F instruction, even considering variations in social structures and government educational funding. A study by Li and Chen (2012) Li and Chen, 2012 indicated that higher education institutions benefit most from research outputs and distance education, with distance education at both undergraduate and graduate levels being more profitable than F2F teaching in Chinese universities. Zhang and Worthington (2017) Zhang and Worthington, 2017 reported increasing cost benefits for distance education over F2F instruction across 37 Australian public universities over a nine-year period (2003-2012). Maloney et al. (2015) Maloney et al., 2015 and Kemp and Grieve (2014) Kemp and Grieve, 2014 also found significant cost savings in higher education through online learning platforms. In Western educational systems, the cost-effectiveness of online learning has been consistently demonstrated Craig, 2015. Studies by Agasisti and Johnes (2015) Agasisti and Johnes, 2015 and Bartley and Golek (2004) Bartley and Golek, 2004 both concluded that the cost benefits of online learning significantly outweigh those of F2F learning in U.S. institutions.

Given the finding of no significant difference in student performance between the two modalities, higher education institutions may consider a gradual shift towards online instruction to reach a wider global audience. Strategic implementation of web-based teaching could expand student enrollment, enhance cost efficiency, and increase university revenue.

The social implications of these findings are significant; however, considerations regarding generalizability are essential. Firstly, this study focused solely on students in a non-STEM environmental science course. The effectiveness of online learning in preparing students for science-based professions, particularly those requiring hands-on experimentation, remains debated. As this course primarily conveys scientific concepts without a laboratory component, these results may not directly translate to online STEM courses for STEM majors or courses with online laboratory co-requisites compared to traditional STEM courses. However, emerging research suggests a changing landscape, with evidence of successful online delivery of STEM core concepts. Biel and Brame (2016) Biel and Brame, 2016 reported successfully transitioning F2F undergraduate biology courses to online formats while maintaining comparable academic success. However, they also noted that in some large-scale courses, F2F sections outperformed online sections in some cases, while others showed no significant difference. A study by Beale et al. (2014) Beale et al., 2014 comparing F2F with hybrid learning in an embryology course found no significant difference in overall student performance, including the performance of lower-performing students. Furthermore, Lorenzo-Alvarez et al. (2019) Lorenzo-Alvarez et al., 2019 demonstrated that online radiology education achieved similar academic outcomes as F2F instruction. Larger-scale research is needed to fully assess the effectiveness of online STEM learning and its impact on workforce development outcomes.

In this study, it is possible that participants possessed pre-existing knowledge or interest in environmental science, potentially influencing the results. Therefore, the study’s focus on a single course is a limitation. However, the findings highlight the potential of this specific course to leverage the flexibility of online learning to engage non-STEM majors in citizen science by effectively teaching core environmental science concepts.

Secondly, using “grade” or “score” as the sole measure of performance may be limited in scope. Course grades may not fully capture true student understanding, especially if grading weights heavily favor group projects or written assignments. Alternative performance indicators, such as standardized exams with both multiple-choice and essay questions, could provide a more comprehensive assessment of subject matter comprehension, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative measures.

Thirdly, the characteristics of the student sample warrant further consideration. It is possible that online students in this study had more available time for coursework compared to their F2F counterparts Summers et al., 2005. Conversely, the convenience sampling method may have limited the representativeness of the student sample. Future research should prioritize more rigorous participant selection methods to ensure a fair representation of diverse student populations, skill levels, and learning styles.

This comparative research study is valuable in addressing a critical educational question by comparing student performance across modalities and demographic factors using a defined performance metric. However, further research is needed to strengthen the evidence base and definitively conclude that online and F2F teaching achieve equivalent outcomes across diverse contexts and disciplines. Future studies should focus on mitigating potential confounding variables and enhancing generalizability to produce more robust and conclusive findings, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of online and traditional teaching effectiveness. The ongoing scientific inquiry into the comparative effectiveness of online and traditional teaching is undoubtedly of increasing importance in the evolving landscape of higher education.

Summary

This comparative research study investigated student learning outcomes in an environmental science course for non-STEM majors, comparing F2F and online instructional modalities and considering gender and class rank as moderating factors. The data indicate that environmental science concepts can be effectively conveyed to non-STEM majors in both traditional and online platforms with comparable student performance, irrespective of gender or class rank. These findings have significant social implications for expanding access to and understanding of scientific concepts among the general population. The accessibility of online courses, often available without formal degree program enrollment, creates opportunities to increase non-STEM majors’ engagement in citizen science by leveraging the flexibility of online learning to deliver core environmental science education.

Limitations of the Study

The study’s limitations primarily stem from the nature of the sample group, variations in student skills and abilities, and potential differences in student familiarity with online instruction. Firstly, the use of a convenience, non-probability sample may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader student populations. Secondly, the study did not control for pre-existing student intelligence or skill levels when comparing groups. It is possible that inherent differences in student aptitude between the F2F and online groups (or across gender and class rank categories) may have influenced the results Friday et al., 2006. Finally, potential differences in familiarity and comfort with online learning technologies could have affected student performance. Students accustomed to traditional classroom settings transitioning to online courses may face a learning curve related to the technology itself, potentially impacting their initial performance Helms, 2014. Future research should explore blended learning approaches, combining elements of both online and F2F instruction, to assess their effectiveness in teaching STEM concepts to non-STEM majors and compare their efficacy to purely online or F2F modalities.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Fort Valley State University Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was not required for this study, as per national legislation and institutional guidelines.

Author Contributions

JP contributed substantially to the study’s conception, data acquisition and analysis, and served as the corresponding author, responsible for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of all aspects of the work. FJ made significant contributions to the study design, data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding

This research was partially supported by funding from the National Science Foundation, Awards #1649717, 1842510, Ñ900572, and 1939739 to FJ.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the reviewers for their insightful comments and feedback, which significantly improved the manuscript.

References

Agasisti, T., and Johnes, G. (2015). Efficiency, costs, rankings and heterogeneity: the case of US higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 60–82. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.818644

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ary, E. J., and Brune, C. W. (2011). A comparison of student learning outcomes in traditional and online personal finance courses. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 7, 465–474.

Atchley, W., Wingenbach, G., and Akers, C. (2013). Comparison of course completion and student performance through online and traditional courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 14, 104–116. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v14i4.1461

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bartley, S. J., and Golek, J. H. (2004). Evaluating the cost effectiveness of online and face-to-face instruction. Educ. Technol. Soc. 7, 167–175.

Beale, E. G., Tarwater, P. M., and Lee, V. H. (2014). A retrospective look at replacing face-to-face embryology instruction with online lectures in a human anatomy course. Am. Assoc. Anat. 7, 234–241. doi: 10.1002/ase.1396

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkesh, M. A., et al. (2009). A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 1243–1289. doi: 10.3102/0034654309333844

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Biel, R., and Brame, C. J. (2016). Traditional versus online biology courses: connecting course design and student learning in an online setting. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 17, 417–422. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v17i3.1157

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bigelow, C. A. (2009). Comparing student performance in an online versus a face to face introductory turfgrass science course-a case study. NACTA J. 53, 1–7.

Columbaro, N. L., and Monaghan, C. H. (2009). Employer perceptions of online degrees: a literature review. Online J. Dist. Learn. Administr. 12.

Craig, R. (2015). A Brief History (and Future) of Online Degrees. Forbes/Education. Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryancraig/2015/06/23/a-brief-history-and-future-of-online-degrees/#e41a4448d9a8

Daymont, T., and Blau, G. (2008). Student performance in online and traditional sections of an undergraduate management course. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 9, 275–294.

Dell, C. A., Low, C., and Wilker, J. F. (2010). Comparing student achievement in online and face-to-face class formats. J. Online Learn. Teach. Long Beach 6, 30–42.

Driscoll, A., Jicha, K., Hunt, A. N., Tichavsky, L., and Thompson, G. (2012). Can online courses deliver in-class results? A comparison of student performance and satisfaction in an online versus a face-to-face introductory sociology course. Am. Sociol. Assoc. 40, 312–313. doi: 10.1177/0092055X12446624

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Friday, E., Shawnta, S., Green, A. L., and Hill, A. Y. (2006). A multi-semester comparison of student performance between multiple traditional and online sections of two management courses. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 8, 66–81.

Girard, J. P., Yerby, J., and Floyd, K. (2016). Knowledge retention in capstone experiences: an analysis of online and face-to-face courses. Knowl. Manag. ELearn. 8, 528–539. doi: 10.34105/j.kmel.2016.08.033

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Helms, J. L. (2014). Comparing student performance in online and face-to-face delivery modalities. J. Asynchr. Learn. Netw. 18, 1–14. doi: 10.24059/olj.v18i1.348

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herman, T., and Banister, S. (2007). Face-to-face versus online coursework: a comparison of costs and learning outcomes. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 7, 318–326.

Kemp, N., and Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-Face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates’ opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Front. Psychol. 5:1278. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01278

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keramidas, C. G. (2012). Are undergraduate students ready for online learning? A comparison of online and face-to-face sections of a course. Rural Special Educ. Q. 31, 25–39. doi: 10.1177/875687051203100405

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Larson, D.K., and Sung, C. (2009). Comparing student performance: online versus blended versus face-to-face. J. Asynchr. Learn. Netw. 13, 31–42. doi: 10.24059/olj.v13i1.1675

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, F., and Chen, X. (2012). Economies of scope in distance education: the case of Chinese Research Universities. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 13, 117–131.

Liu, Y. (2005). Effects of online instruction vs. traditional instruction on student’s learning. Int. J. Instruct. Technol. Dist. Learn. 2, 57–64.

Lorenzo-Alvarez, R., Rudolphi-Solero, T., Ruiz-Gomez, M. J., and Sendra-Portero, F. (2019). Medical student education for abdominal radiographs in a 3D virtual classroom versus traditional classroom: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Roentgenol. 213, 644–650. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21131

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lundberg, J., Castillo-Merino, D., and Dahmani, M. (2008). Do online students perform better than face-to-face students? Reflections and a short review of some Empirical Findings. Rev. Univ. Soc. Conocim. 5, 35–44. doi: 10.7238/rusc.v5i1.326

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Maloney, S., Nicklen, P., Rivers, G., Foo, J., Ooi, Y. Y., Reeves, S., et al. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis of blended versus face-to-face delivery of evidence-based medicine to medical students. J. Med. Internet Res. 17:e182. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4346

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mann, J. T., and Henneberry, S. R. (2014). Online versus face-to-face: students’ preferences for college course attributes. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 46, 1–19. doi: 10.1017/S1074070800000602

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mozes-Carmel, A., and Gold, S. S. (2009). A comparison of online vs proctored final exams in online classes. Imanagers J. Educ. Technol. 6, 76–81. doi: 10.26634/jet.6.1.212

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Richardson, J. C., and Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to student’s perceived learning and satisfaction. J. Asynchr. Learn. 7, 68–88.

Roval, A. P., and Jordan, H. M. (2004). Blended learning and sense of community: a comparative analysis with traditional and fully online graduate courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 5. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v5i2.192

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Salcedo, C. S. (2010). Comparative analysis of learning outcomes in face-to-face foreign language classes vs. language lab and online. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 7, 43–54. doi: 10.19030/tlc.v7i2.88

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stern, B. S. (2004). A comparison of online and face-to-face instruction in an undergraduate foundations of american education course. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. J. 4, 196–213.

Summers, J. J., Waigandt, A., and Whittaker, T. A. (2005). A comparison of student achievement and satisfaction in an online versus a traditional face-to-face statistics class. Innov. High. Educ. 29, 233–250. doi: 10.1007/s10755-005-1938-x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tanyel, F., and Griffin, J. (2014). A Ten-Year Comparison of Outcomes and Persistence Rates in Online versus Face-to-Face Courses. Retrieved from: https://www.westga.edu/~bquest/2014/onlinecourses2014.pdf

Werhner, M. J. (2010). A comparison of the performance of online versus traditional on-campus earth science students on identical exams. J. Geosci. Educ. 58, 310–312. doi: 10.5408/1.3559697

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Westhuis, D., Ouellette, P. M., and Pfahler, C. L. (2006). A comparative analysis of on-line and classroom-based instructional formats for teaching social work research. Adv. Soc. Work 7, 74–88. doi: 10.18060/184

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wladis, C., Conway, K. M., and Hachey, A. C. (2015). The online STEM classroom-who succeeds? An exploration of the impact of ethnicity, gender, and non-traditional student characteristics in the community college context. Commun. Coll. Rev. 43, 142–164. doi: 10.1177/0091552115571729

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xu, D., and Jaggars, S. S. (2016). Performance gaps between online and face-to-face courses: differences across types of students and academic subject areas. J. Higher Educ. 85, 633–659. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2014.0028

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, L.-C., and Worthington, A. C. (2017). Scale and scope economies of distance education in Australian universities. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 1785–1799. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1126817

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: Comparative Research Study, face-to-face learning, online learning, e-learning, higher education, student performance, environmental science education, non-STEM majors, instructional modality, educational technology.

Citation: Paul J and Jefferson F (2019) Comparative Research Study: Online vs. Face-to-Face Learning Effectiveness in an Environmental Science Course From 2009 to 2016. compare.edu.vn. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2019.00007

Received: 15 May 2019; Accepted: 15 October 2019; Published: 12 November 2019.

Edited by:

Xiaoxun Sun, Australian Council for Educational Research, Australia

Reviewed by:

Miguel Ángel Conde, Universidad de León, Spain Liang-Cheng Zhang, Australian Council for Educational Research, Australia

Copyright © 2019 Paul and Jefferson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jasmine Paul, cGF1bGpAZnZzdS5lZHU=