Comparative advertising is a potent tool in the marketing arsenal, but it’s crucial to understand where it fits within the broader spectrum of competitive strategies. This article delves into the nuances of comparative advertising, contrasting it with general competitive approaches, exploring its history, effectiveness, and potential pitfalls. By examining historical examples and expert insights, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of how comparative advertising can be strategically employed, or when a more subtle competitive approach might be more beneficial.

The initial question posed was direct: Is it detrimental for companies to publicly criticize their rivals? This immediately brings to mind comparative advertising, which, for our discussion, we’ll define broadly as: advertising that mentions or implies competitors to highlight the superiority of the advertised product or service. This raises a secondary, equally important question: Is comparative advertising a relic of the past, and if so, what lessons can be gleaned from its history?

These questions arise from recent instances of service companies within the podcasting industry publicly critiquing their competition. While not formal advertising campaigns, these actions echo the principles of comparative advertising. The core distinction lies in intent and planning. Advertising, particularly comparative advertising, is a deliberate, calculated strategy where potential repercussions are considered. Public pronouncements, on the other hand, require real-time responsiveness and carry a different set of risks.

Regardless of the forum, whether a paid advertisement or a public statement, directly attacking competitors carries inherent risks. The most significant is the potential for backlash and distraction. Engaging in protracted advertising wars can divert resources – time, energy, and finances – away from crucial areas like product innovation and service enhancement. Instead of focusing on internal improvements and customer acquisition, companies become embroiled in reactive battles.

The intensity and potential futility of these “wars” are aptly illustrated by the decade-long conflict between Tylenol and Advil. Federal Judge William C. Conner famously remarked that this advertising battle was more resource-intensive than some nations’ struggles for survival. Beyond the financial burden, such campaigns can negatively impact public perception of all brands involved. As one participant in the “Soup Wars” lamented, vast sums were being spent to essentially convince consumers that competitors’ products were inferior, while the overall market category declined.

Despite the risks and costs, the question of effectiveness remains. Does comparative advertising actually work? Historical analysis and research offer some guidelines.

Tracing back to the 19th century, advertising was dominated by the exaggerated claims of patent medicines. These “miracle cures,” often containing questionable ingredients, relied on pure hype and extensive advertising budgets fueled by enormous profit margins. The rise of railroads and newspapers facilitated nationwide advertising, and “snake oil salesmen” became a cultural archetype.

The 20th century ushered in a new era of advertising professionalism. Reacting against the blatant falsehoods of the past, advertisers embraced “Reason-Why Advertising,” emphasizing truthfulness and well-crafted, persuasive copy. Figures like John E. Kennedy championed “Salesmanship-In-Print,” advocating for a no-nonsense, factual approach. Books like John Caples’ “Tested Advertising Methods” and Claude Hopkins’ “Scientific Advertising” exemplified this focus on data-driven, results-oriented advertising.

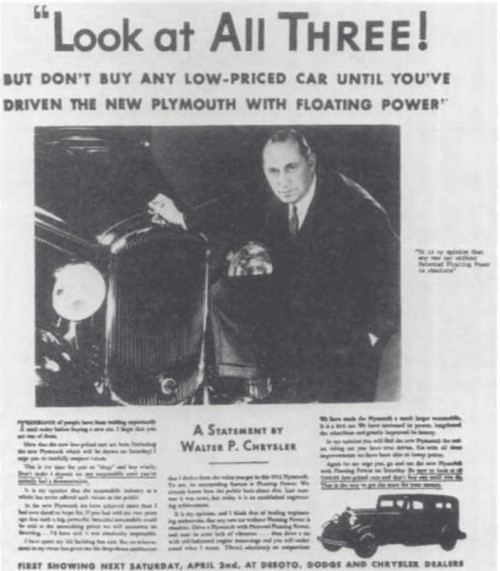

One early example of comparative advertising emerged during this period. In 1932, J. Stirling Getchell created an ad for Chrysler’s Plymouth, directly comparing it to Ford and General Motors. The ad, featuring Walter Chrysler, urged consumers to “Look at All THREE!”, implicitly highlighting Plymouth’s superior value without explicitly naming competitors. This campaign proved highly successful, boosting Plymouth’s sales and market share significantly. Interestingly, while comparative, it maintained a degree of subtlety.

However, the prevailing wisdom of the mid-20th century leaned away from direct comparison. As advertising columnist George Laflin (Aesop Glim) wrote in 1945, it was often better to “ignore your competition” and “tell your own story – exclusively, positively.” The emphasis was on building brand strength through positive messaging, rather than competitor bashing.

The advertising landscape shifted dramatically in the latter half of the 20th century. Post-war economic expansion, the rise of television, and evolving advertising philosophies all contributed to a more competitive environment. Concepts like Bill Bernbach’s creative teams, “Big Idea” advertising, and Rosser Reeves’ Unique Selling Proposition (USP) emphasized differentiation and capturing consumer attention in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) actively encouraged comparative advertising in the early 1970s, believing it fostered competition and provided consumers with more information. This opened the floodgates, leading to more direct and combative advertising. “Advertising Wars” became commonplace, prompting legislative adjustments like the Trademark Law Revision Act of 1988, designed to protect against false or misleading comparative claims.

Prior to this, the Lanham Act of 1946 only prohibited false claims about one’s own products, not competitors’. This legal evolution reflects the changing attitudes towards comparative advertising. Research by Fred Beard analyzing decades of advertising publications confirmed a significant shift: the belief that “competitors should be ignored” largely vanished in the latter half of the 20th century.

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed numerous high-profile “Advertising Wars,” from the “Cola Wars” to the “Console Wars” and “Burger Wars.” These battles involved substantial investments of resources in attacking competitors.

The effectiveness of comparative advertising is situational. It can be advantageous for underdogs or challengers seeking to gain market share. Pepsi and Burger King, as perennial underdogs, have consistently employed comparative tactics. Similarly, Plymouth’s “Look at All THREE!” campaign and Apple’s “Get a Mac” campaign successfully challenged market leaders without resorting to overtly negative attacks. These examples often “punch up,” targeting the market leader with a comparative message.

However, for market leaders, engaging in direct comparative advertising can be riskier. It can elevate the competitor’s brand and draw unnecessary attention to the competition. The advice from a 1903 Printer’s Ink article remains relevant: “Talk success in your advertising, ignore competitors, and make your offering of vital interest.”

Let’s examine some post-1950 examples of comparative advertising:

1957: Dove vs. Ordinary Soaps – Categorically Different

✊ PUNCHING UP: Dove’s initial television advertisement pioneered comparative advertising by contrasting Dove beauty bar with “ordinary soap.” The ad highlighted Dove’s unique “one-quarter cleansing cream” and its moisturizing benefits compared to the drying effects of typical soaps. Similar to the “Look at All THREE!” approach, it encouraged viewers to make their own comparison without directly naming competitor brands.

1962: Avis vs. Hertz – Almost There

✊ PUNCHING UP: DDB’s iconic “We try harder” campaign for Avis leveraged their number two market position in car rentals. While not explicitly naming Hertz, the campaign cleverly played on the audience’s awareness of the market leader. This indirect comparison positioned Avis as the determined underdog, striving for excellence. Interestingly, the ad design deliberately omitted the Avis logo, showcasing the agency’s confidence in the messaging itself. Decades later, Avis remains a strong number three, embodying the “We try harder” ethos.

1975: Pepsi vs Coke – Challenged Challenger

✊ PUNCHING UP: The “Pepsi Challenge” is arguably the most iconic example of direct comparative advertising. Pepsi directly challenged Coke with blind taste tests, demonstrably showing consumer preference for Pepsi in single sips. This aggressive campaign significantly boosted Pepsi’s market share and forced Coke to acknowledge the challenge. Despite its success, Pepsi never surpassed Coke in overall market dominance, highlighting the “Pepsi Paradox”: winning taste tests doesn’t always translate to market leadership.

1982: MCI vs. Bell – The Proof is in the Parody

✊ PUNCHING UP: MCI, leveraging microwave technology to offer lower long-distance rates than AT&T (Bell System), employed humor in their comparative advertising. They famously parodied Bell’s sentimental “Reach out and touch someone” ads, highlighting the high cost of AT&T’s service compared to MCI’s affordability. The parody ads effectively conveyed MCI’s value proposition through direct comparison and comedic contrast.

1992: Sega vs. Nintendo – Losing the Long Game

✊ PUNCHING UP: Sega’s aggressive entry into the video game console market in the 1990s exemplified combative comparative advertising. Their “Genesis does what Nintendon’t” campaign directly attacked Nintendo, the market leader. Sega achieved significant market share gains initially through this aggressive approach. However, Nintendo ultimately maintained long-term dominance, illustrating that aggressive comparative advertising, while effective short-term, doesn’t guarantee lasting victory. Nintendo’s strategy was to largely ignore Sega’s attacks, portraying them as a sign of desperation.

2006: Mac vs. PC – Mr. Nice Metaphor

✊ PUNCHING UP: Apple’s “Get a Mac” campaign is considered a masterclass in effective comparative advertising. Using humor and relatable characters (Justin Long as “Mac” and John Hodgman as “PC”), Apple subtly highlighted the perceived advantages of Macs over PCs without resorting to direct negativity. This campaign significantly boosted Apple’s brand reputation and sales. The campaign’s success stemmed from its positive, metaphorical approach to comparison, contrasting sharply with more aggressive tactics.

2016: GM vs. Ford – Comparison Adds Sales

🤜 PUNCHING ACROSS: GM’s comparative campaign in 2016 directly targeted Ford, comparing Chevrolet truck beds’ steel construction to Ford’s aluminum beds. While GM saw sales increases, Ford’s F-Series sales actually increased at a higher rate during the campaign period. This example illustrates that even direct comparative advertising can sometimes inadvertently benefit the competitor, highlighting the complexities of such strategies.

2018: Burger King vs. McDonalds – Forever Underdog

✊ PUNCHING UP: Burger King’s long-standing rivalry with McDonald’s continues to fuel comparative advertising campaigns. “The Whopper Detour” campaign, which offered discounted Whoppers near McDonald’s locations, exemplified Burger King’s underdog strategy. While these campaigns generate buzz and awards, McDonald’s market dominance remains unchallenged, reinforcing Burger King’s perpetual underdog status. However, this competition drives innovation and benefits consumers through evolving brand offerings.

2021: Samsung vs. Apple – Feeling Features

✊ PUNCHING UP: Samsung’s 2021 campaign directly compared Samsung phones to Apple iPhones, highlighting feature differences. Positioning Samsung above Apple in side-by-side comparisons, the ads questioned whether upgrading to an iPhone was a “downgrade.” As a market challenger to Apple’s dominant position, Samsung’s comparative approach aims to gain market share by directly addressing perceived shortcomings of the competitor’s product. Samsung’s history of “trolling” Apple suggests a desire to surpass Apple’s market leadership.

In conclusion, while comparative advertising can be a valuable tool, especially for challenger brands, it’s not without risks. The decision to engage in comparative advertising versus focusing solely on promoting one’s own brand strengths requires careful strategic consideration. Understanding the historical context, potential backlash, and nuanced effectiveness of different comparative approaches is crucial for making informed marketing decisions. Often, a more subtle, “punching up” approach, or focusing on positive brand messaging, can yield more sustainable long-term results than overtly aggressive competitive tactics.