Delyle T. Polet*†John R. Hutchinson*†

- Structure and Motion Lab, Comparative Biomedical Sciences, Royal Veterinary College, Hatfield, United Kingdom

Fossil trackways offer a window into the behavior of extinct animals. While they provide valuable information about the size, stride, and even speed of the trackmaker, the actual gait of the organism can remain unclear. This is particularly true for quadrupedal animals, where different gaits can produce similar trackway patterns. In this study, predictive simulation using trajectory optimization is employed to help distinguish the gaits used by trackmakers. Initially, it was demonstrated that a planar, five-link quadrupedal biomechanical model can replicate the qualitative trackway patterns observed in domestic dogs, although a systematic error was noted in the track phase (relative distance between ipsilateral pes and manus prints). Subsequently, trackway dimensions were used as inputs for a model of Batrachotomus kupferzellensis, a long-limbed, crocodile-line archosaur (clade Pseudosuchia) from the Middle Triassic of Germany. Energetically optimal gaits were identified and their predicted track phases were compared to those of fossil trackways of Isochirotherium and Brachychirotherium. The optimal results align with trackways at slower speeds but diverge at faster speeds. However, all simulations indicate a gait transition around a non-dimensional speed of 0.4 and another at 1.0. The trackways also exhibit significant differences in the track phase at these speeds. Notably, even when simulations are constrained to the fossil track phase, the optimal simulations after the first gait transition do not correspond to a trot, which is commonly used by living crocodiles. Instead, they reveal a diagonal sequence gait akin to the slow tölt of Icelandic horses. This finding provides the first evidence that extinct pseudosuchians may have exhibited gaits unlike those of their modern crocodile relatives and suggests a gait transition in an extinct pseudosuchian. The outcomes of this analysis emphasize areas for model improvement to generate more reliable predictions for fossil data, while also highlighting the potential of simple models to offer insights into the behavior of extinct animals, especially when comparing archosaur locomotion to that of crocodiles.

Introduction

Despite the astonishing diversity of animals today, the past holds creatures with no perfect modern counterparts. Batrachotomus kupferzellensis (Gower, 1999) exemplifies this. This long-limbed, crocodile-line archosaur (Pseudosuchia clade) from the Middle Triassic of Germany possessed a large head and substantial tail reminiscent of modern crocodylians, but also a more erect (adducted) limb posture similar to contemporary (cursorial) mammals (Gower and Schoch, 2009). This unique combination raises questions about its locomotion: Was Batrachotomus‘s movement more akin to a mammal, a modern crocodylian, or something entirely different? Understanding how archosaurs like Batrachotomus moved in comparison to crocodiles and mammals is crucial for grasping the evolution of terrestrial locomotion.

Bonaparte (1984) proposed that the erect limbs, along with elongated pubis and ischium, of “rauisuchids” (a group including Batrachotomus) were adaptations for parasagittal locomotion. These adaptations may have been crucial for their survival during a significant Middle–Late Triassic faunal turnover. Parrish (1986) further suggested that the erect limbs in “rauisuchians” and other archosaurs provided enhanced maneuverability on land, similar to that seen in mammals. While Parrish acknowledged similarities between their hindlimb plantigrady and crurotarsal ankle and those of modern crocodylians, he also noted that the ankle reorganization led to symmetrical plantarflexor pull. This resulted in simple plantarflexion of the ankle, unlike the lateral rotation coupled with plantarflexion observed in crocodylians and lizards. Nesbitt et al. (2013) interpreted plantigrady and the extended calcaneal tuber as adaptations for high power rather than high speed. While there is a consensus that Batrachotomus employed parasagittal and erect locomotion and was quadrupedal (Bishop et al., 2020), the specific types of gait it may have utilized remain unanalyzed. Comparing the potential gaits of this archosaur to the known gaits of crocodiles is essential to understanding its place in locomotor evolution.

Much of our understanding of gait selection in cursorial, quadrupedal mammals stems from work-based optimization in simplified parasagittal models. Trajectory optimization, in particular, allows for the numerical optimization of continuous motion over time. Xi et al. (2016) successfully used trajectory optimization with a planar model to recover the four-beat walk and trot, gaits commonly used by mammals. Galloping was subsequently found to be optimal when a compliant torso was incorporated (Yesilevskiy et al., 2018). By minimizing mechanical work in parasagittal models, it was demonstrated that the body’s pitch moment of inertia (when normalized to glenoacetabular distance and mass as the Murphy number) largely determines which mammals do and do not trot (Usherwood, 2020; Polet, 2021b).

Surprisingly, detailed anatomical precision is often not necessary for biomechanical models to achieve solutions comparable to the animals they represent. For instance, a model with a single rigid body element, massless prismatic legs, and no elastic components accurately captured walking and trotting in dogs. This model matched gait transition speed, changes in duty factor with speed, ground reaction force shape, and limb phase with reasonable accuracy by minimizing a cost function that combined limb work with a penalty for rapid force changes (Polet and Bertram, 2019). Such simplified models can be invaluable in paleontological research, where soft-tissue details like muscle geometry, fiber length, and tendon length are typically not preserved. Indeed, determining the gaits of fossil organisms from trackways is often challenging, although some attempts have shown broad success (see Nyakatura et al., 2019; Vincelette, 2021).

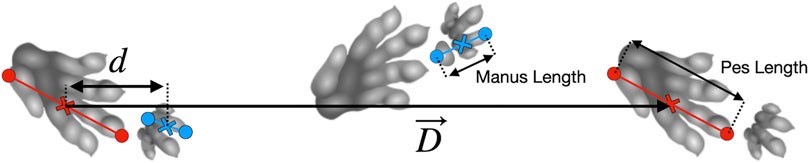

Triassic pseudosuchian fossil trackways, classified under the ichnotaxa Isochirotherium and Brachychirotherium, may have been created by Batrachotomus or a closely related species (Petti et al., 2009; Diedrich, 2015; Apesteguía et al., 2021; Klein and Lucas, 2021). These trackways provide information about the approximate size of the trackmaker and gait parameters, such as track phase (defined as ipsilateral pes to manus displacement divided by stride length, Figure 1). However, the precise gait employed by these trackmakers, and how it compares to the gaits of crocodiles or other archosaurs, remains an open question.

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 1. Schematic of a Brachychirotherium trackway, showing definition of parameters. Footprints are measured from the caudal-most point to the tip of digit III, or to digit II in the case of Brachychirotherium manus. The caudal side of digit V was used (e.g., the second manus in the diagram) when available. The manus–pes distance is calculated between midpoints along the stride vector, D→; the track phase is then d/D. Trackway adapted from Wikimedia Commons (2010), used here under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

A biomechanical model can offer quantitative predictions of track phase based on stride length and trackmaker size. If the model accurately predicts the track phase, it not only supports the use of a specific gait but also provides insights into other aspects of the trackmaker’s locomotion that are not directly evident from fossil trackways. This approach can be particularly useful for comparing the locomotor strategies of extinct archosaurs with those of their living relatives, like crocodiles.

Methods

Planar Model and Optimization Scheme

The parasagittal, planar model utilized in this study is based on the work of Polet and Bertram (2019) and Polet (2021b). It features a rigid trunk and massless legs that exert force along an axis connecting the footfall location to either the acetabulum or glenoid throughout the stride (Figure 2). Feet are simplified as points, actuator force is instantaneously reflected in ground reaction force, and sliding friction is considered infinite. The center of mass (COM) is positioned along the glenoacetabular axis, and the model is provided with the pitch moment of inertia (MOI), stride length (D), and average horizontal speed as inputs.

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 2. Simple quadrupedal model used for simulations overlayed on the skeletal model used for length measurements. White circles show radius of gyration from the center of mass (x). Only two of four legs (red and blue lines) are shown in the figure.

The optimization process aims to minimize an objective function J, which combines axial limb work with a regularization term that penalizes rapid changes in force, as expressed by the following equation:

J=∑i∫0TFiL˙+cFi2˙dt,(1)

Here, Fi represents the axial force of the ith limb, L is the axial limb length, c is the force-rate penalty parameter, and 0 ≤t ≤T denotes the time within a stride. The penalty on the force rate ensures continuity in force and velocity, preventing instantaneous collisions. However, when force-rate penalties are low, near-impulsive solutions (quasi-collisions with sharp force peaks) can still emerge as force rates are decision variables.

In the optimization scheme, c is normalized as c′=cMgLBT, where LB is the glenoacetabular distance, M is the body mass, and g is the acceleration due to gravity (Polet and Bertram, 2019). Throughout this paper, dimensionless variables are indicated by a prime symbol. The reported values of c′ are for UH′=0.4 (where UH′=U/gH, U is the average horizontal speed, g is acceleration due to gravity, and H is hip height) and are scaled appropriately according to T (to maintain the same c).

Force rates act as controls in the model, while forces, velocities, and positions are treated as states. A leg-impulse state is incorporated to prevent simultaneous cranial and caudal contact of a single leg. Footfall positions are parameters and also decision variables in the optimization. Additional relaxation parameters and slack variables are included as controls to regularize complementarity conditions, as detailed in Polet and Bertram (2019).

Given that the gaits of interest are symmetrical, the simulation is conducted over a half cycle (time from 0 to T/2). An initial and final COM horizontal position of 0 and D/2 is imposed. Periodicity is enforced by constraining the body kinematics to be identical at t=0 and T/2, and left-side forces at t=0 to equal right-side forces at t=T/2. The vertical positions of hips and shoulders are constrained to remain above ground, and the torso orientation (relative to horizontal) is restricted to [−π/2,π/2]. Bounds on other parameters, states, and controls are set to be sufficiently large to be effectively unconstrained. This implementation allows the optimizer to select any symmetrical contact sequence and duty factor for a given speed and stride length.

Optimal gaits are determined through trajectory optimization with direct collocation using GPOPS-II (v. 2.3) (Patterson and Rao, 2014) and SNOPT (v. 7.5) (Gill et al., 2005; Gill et al., 2015) in MATLAB 2020b. For each parameter combination, only the best local optimum from at least 50 random initial guesses is retained. The custom software used to generate symmetrical solutions is publicly available on GitHub (Polet, 2021a).

In the baseline unconstrained scenario, different force-rate penalties were compared, allowing the optimizer to freely choose the track phase. In the constrained scenario, the optimizer was forced to adopt the track phase that matched fossil trackway trends. A sensitivity analysis was also performed by increasing forelimb length while keeping the track phase unconstrained. In all cases, diagonal sequence and lateral sequence gaits are considered equivalent due to the model’s planar nature. The ipsilateral limb phase (ϕL, defined as the time from hindlimb contact to ipsilateral forelimb contact divided by the stride period) from dog model optimization results was modulated to the range 0<ϕL<0.6, while for the Batrachotomus model, it was modulated to 0.4 <ϕL<1.

Morphology: Domestic Dogs and Batrachotomus

Model track phase predictions were validated against gait and footfall data available for Belgian Malinois dogs (Maes et al., 2008), using body proportions from Polet and Bertram (2019) and MOI from Polet (2021b). Batrachotomus dimensions and inertial properties were derived from a volumetric model (Bishop et al., 2020), based on the skeletal reconstruction at the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart. Due to the fragmentary nature of manus and pes material for Batrachotomus, the autopodia were partially reconstructed by museum staff based on closely related species. It was assumed that this reconstructed autopodial morphology was sufficiently accurate for the purposes of this study. Gower and Schoch (2009) mentioned that specimen SMNS 90018 includes two fragmentary metacarpals and phalanges of the right manus, and “four metatarsals, several phalanges, and a few distally incomplete unguals,” of which only the fifth metatarsal was certainly identifiable. However, the preserved elements of the autopodial morphology are consistent with: (1) the morphology of the reconstructed, mounted museum display specimen, which shows a relatively smaller manus compared to the pes; and (2) the general autopodial morphology of other “rauisuchian”-grade Pseudosuchia, which also exhibit a smaller manus relative to the pes. The model was posed in an approximate standing posture to determine leg lengths and pitch MOI about the COM (Figure 2; Table 1). The “COM forelimb bias,” representing the presumed percentage of weight support in Batrachotomus (see Henderson, 2003; Willey et al., 2004), was calculated as the distance from the hip to COM along the glenoacetabular axis, divided by LB. For dogs, the COM forelimb bias was derived from Griffin et al. (2004).

TABLE 1

TABLE 1. Body parameters used as inputs to the models.

Trackway Data

The ichnotaxa Isochirotherium and Brachychirotherium are generally attributed to large pseudosuchian trackmakers, potentially “rauisuchians” like Batrachotomus or related forms (Diedrich, 2015; Apesteguía et al., 2021; Hminna et al., 2021; Klein and Lucas, 2021). Trackway data of interest include stride length, pes and manus length, and ipsilateral pes to manus distance within a footprint “set.” For each trackway examined, all available trackway data were compiled. For instance, all pes lengths were used to calculate the mean pes length, even if some were not associated with a manus. These data were collected from published sources, which sometimes assigned trackways to ichnospecies. However, for this analysis, ichnotaxa were grouped at the ichnogenus level.

Data from Tables

Published table data were utilized where available (Petti et al., 2009; Diedrich, 2012; Diedrich, 2015). The manus–pes distance was consistently reported as inter-print distance (IPD). In these cases, the midpoint–midpoint distance was calculated as (Pes Length + Manus Length)/2 + IPD.

Petti et al. (2009) classified four trackways as Brachychirotherium (identified as BsZ-A, -D, -E, and -F). Only BsZ-A and BsZ-D provided manus–pes distance and were included in this study. Diedrich (2012) reported three Isochirotherium trackways in Table 1, with the values interpreted as means. Variational statistics were not provided, except for the number of manus/pes sets. Diedrich (2015) presented a single Isochirotherium trackway in their Table 1 with data for each manus/pes set. Stride lengths were reported in this table for every third manus/pes set.

Data from figures

Additional trackway data were extracted from published orthogonal-view photographs or trackway traces using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004). Generally, for each pes print, the tip of the third digit and the caudal-most point of the fifth digit were digitized, with the craniocaudal axis defined along the axis of the third digit (Figure 1). If the fifth digit was absent, the caudal-most point of the metatarsal pad was used. This procedure was repeated for manus tracks, except for Brachychirotherium. Due to the manus rotation in this ichnogenus, the second digit was used for the craniocaudal axis, and the tip was digitized accordingly.

Midpoints for each manus or pes were calculated, and the stride vector was defined as the displacement between midpoints of successive pes footfalls on the same side (D→). The midpoint was chosen as it likely represents the average center of pressure for footfalls and reduces sensitivity to accurate single-point measurements. The manus–pes midpoint vector is the displacement from pes to manus midpoint (d→). The manus–pes distance was then calculated as the length of the projection of this vector onto the average stride vector for the trackway (d→⋅D→av/||D→av||).

Clark and Corrance (2009) presented photos of single manus–pes sets of Isochirotherium, which were digitized as described above. The set from their Figure 7B was associated with trackway BWF_5 data in Table 1 of Clark et al. (2002), where the trackway was initially assigned to Chirotherium. The trackway set from Figure 6C of Clark and Corrance (2009) was associated with trackway SLID_1 data in their Table 1. However, the digitized pes in this case had a much smaller length (0.13 m) than the smallest reported value in their Table 1 (0.21 m). Based on the trackway photo (Figure 6 in Clark et al., 2002), the pes was the sixth print of SLID_1 in their Table 1, and the caudal portion of the print may have been cropped from the photo in Figure 6C of Clark and Corrance (2009). To correct this, the caudal point was extended by the pes 6 length reported in their Table 1 (0.28 cm). As orthogonal views were unavailable for either trackway, projection to stride could not be performed, and the absolute distance from pes to manus midpoint was used instead. Pes length data for the final print in BWF_5 were excluded due to poor preservation.

Apesteguía et al. (2021) assigned four trackways to Brachychirotherium, identified as R1, R2-t1, -t5, and -t9, and presented in their Figures 4A, 5B. Trackway R1 includes a trailing left manus without an associated pes. Therefore, a manus–pes midpoint distance to the subsequent left pes was calculated and subtracted from the stride length to obtain the pes–manus midpoint distance. The same left pes was used to calculate the pes–manus midpoint distance for the next left manus print. Trackway R2-t1 appeared to have a slight turn at the beginning, evident in manus–pes sets 1 and 2. The rest of the trackway appeared straight and steady. Consequently, the first two manus–pes sets were omitted for track phase or stride length calculations but included for trackmaker size estimation. The prints in trackway R2-t5 were relatively poorly preserved, but sufficiently preserved to identify the ichnotaxon (Brachychirotherium). For this trackway, the cranial-most and caudal-most points of each print were digitized, with craniocaudal direction defined as the trackway direction where digits were indistinguishable.

Klein et al. (2006) reported a single Brachychirotherium trackway in their Figure 7. As the digits of the first manus were indistinguishable, the cranial-most portion of the print along the trackway direction was used.

Hminna et al. (2021) reported a single Brachychirotherium trackway in their Figure 4. This trackway contained only one set of well-preserved sequential ipsilateral pes footprints. Therefore, sequential ipsilateral manus footprints were used to measure stride length (total of 4 in the trackway).

Calculation of Gait Parameters

Hip height of the trackmaker was estimated by multiplying the mean track pes length by the ratio of hip height to pes length in the Batrachotomus model. The non-dimensional speed (UH′=U/gH) was estimated from the non-dimensional stride length (DH′=D/H, where D is stride length) using Alexander’s (1976) dynamic similarity relation:

UH′=0.25DH′1.67.(2)

Trackway stride length and speed were model inputs, while track phase was compared with optimization predictions. An analytical approximation (Stevens et al., 2016) for track phase (ϕT) as a function of ipsilateral limb phase (ϕL), with LBx being the horizontal glenoacetabular distance, was calculated as:

ΦT=mod(ΦL+LBx/D,1).(3)

This was also compared to trackway and optimization results. LBx is derived from LB, the absolute glenoacetabular distance, as LBx=LB2−(LH−LF)2 in standing (Figure 2).

LBx can be directly estimated from trackways assuming periods of quadruple stance (when all limbs are simultaneously in contact). For a trot, this parameter is the distance from the midpoint between left and right pes prints to the midpoint between subsequent left and right manus prints. For this study, this is equivalent to:

LBx=d+D/2.(4)

See Supplementary Figure S1 for a geometric proof. While Stevens et al. (2016) demonstrated potential ambiguities in these estimates for small stride lengths, the stride lengths in this study are sufficiently large to avoid ambiguity regarding prints in simultaneous contact (assuming quadrupedal stance).

Results

Belgian Malinois Dogs

For dogs, optimization predicts a lateral sequence gait with a limb phase ϕL=0.25 transitioning to a trot with ϕL=0.5, which aligns with natural canine behavior (Figure 3). The predicted track phase falls within the natural variation range (2 standard deviations, from Maes et al., 2008) and captures the trend of track phase change with speed, although it is consistently below the mean empirical value.

FIGURE 3

FIGURE 3. Dog track phase decreases with speed, before exhibiting a jump at the walk-trot transition. The lines of best fit to empirical data are from Maes et al. (2008), with filled areas representing two standard deviations from the mean. Black solid and dotted lines indicate ϕL=0.25 and 0.5, respectively.

Varying the force-rate penalty c has minimal qualitative impact on optimization results, except for the walk–trot transition point. The natural walk–trot transition in dogs occurs around UH′=0.8. In simulations, the transition point shifts from approximately UH′=0.7 at the highest force-rate penalty (c′=3×10−3) to UH′=0.8 at the lowest (c′=3×10−5). Polet and Bertram (2019) concluded that c′=3×10−3 best matches dog duty factors and ground reaction force profiles at an intermediate walking speed. Ground reaction forces at this force-rate penalty (Figure 4) qualitatively resemble the double-humped profile of walking (Jayes and Alexander, 1978) and the single-humped profile of trotting (Bertram et al., 2000) in dogs.

FIGURE 4

FIGURE 4. Ground reaction forces from predictive simulation at a walking speed (A) and trotting speed (B) in a dog model with force-rate penalty c′ of 3×10−3. Note that any symmetrical profile is allowed, yet the simulation correctly predicts double-humped walking profiles at slow speeds and single-humped trotting profiles at faster speeds.

Trackway Data

Trackways exhibited variability in size and length, with mean pes lengths ranging from 0.22 to 0.34 m in Isochirotherium and 0.12 to 0.39 m in Brachychirotherium (Table 2). Isochirotherium normalized speed (estimated using Eq. 2) varied from 0.40 to 0.79, characteristic of moderate to fast walking or slow running. Brachychirotherium speeds showed greater variation, from slow walking at 0.31 to fast running at 1.92. The mean manus to pes length ratio across all trackways was 0.35 ± 0.05 for Isochirotherium and 0.38 ± 0.09 for Brachychirotherium (±standard deviation).

TABLE 2

TABLE 2. Summary data for Isochirotherium and Brachychirotherium trackways. Values are means ± standard deviation (sample size). Speed is normalized to presumed hip height. ET, Early Triassic; MT, Middle Triassic; LT, Late Triassic; A, Anisian; C, Carnian; N, Norian; S, “Scythian.”

Overall, fossil trackways show a sharp decrease in track phase with increasing speed at lower speeds, following the analytical line for a trot (Figure 5). Above UH′=0.6, the track phase stabilizes at approximately 0.15 until UH′=1, where it drops sharply to about 0.10.

FIGURE 5

FIGURE 5. Track phase plotted against speed for Batrachotomus vs. fossil chirotheriid trackways. Different levels of the force-rate penalty c′ are shown as different symbols. The lowest force-rate penalty of 3×10−5 best fits trackway data. Both simulation and trackway data show a gradual reduction in the track phase at slow walking, corresponding to a trot based on the analytical curve (dashed line). This changes abruptly to a constant track phase with increasing speed, corresponding to the increased limb phase according to the analytical curves. Near UH′=1, the theoretical upper limit for pendular walking, both simulation and trackway data exhibit a sharp reduction in the track phase, shifting toward a diagonal sequence singlefoot walk (ϕL=0.75). At intermediate speeds, the simulation consistently overestimates the trackway phase. Silhouette of Batrachotomus by Scott Hartman, used under a CC BY 3.0 license.

The horizontal glenoacetabular distance (LBx) was estimated from trackways using Eq. (4) for estimated non-dimensional speeds below 0.4 (where quadruple limb stance may have occurred). Only two trackways meet this criterion, both Brachychirotherium (Apesteguía et al., 2021, trackways R1 and R2-t5), yielding LBx/LP estimates of 3.11 and 2.95, respectively (where LP is mean pes length). The reconstructed Batrachotomus model has LBx/LP=2.85 and LB/LP= 3.08.

Scaling fossil trackways to the Batrachotomus reconstruction results in estimated LBx of 0.81 and 0.79 m. The reconstruction itself gives LBx = 0.74 m and LB=0.80 m.

Batrachotomus Simulation Results

Optimization predicts that Batrachotomus would have used a walking trot at slower speeds (UH′≤0.4), transitioning to a diagonal sequence gait at faster speeds (Figure 5). The walking trot is characterized by a sharp reduction in track phase with increasing speed. With higher force-rate penalties, the transition to a diagonal sequence, singlefoot gait involves a discontinuity in track phase around UH′=0.4. At the lowest force-rate penalty (c′= 3×10−5), the track phase jumps to a plateau, remaining constant at approximately 0.33 while the limb phase gradually increases. As the limb phase approaches a diagonal sequence in singlefoot (ϕL=0.75), the track phase decreases sharply again with increasing speed, maintaining a roughly constant limb phase.

At the highest force-rate penalty, the walking trot exhibits typical “vaulting” double-humped ground reaction force profiles (Figure 6A), with simultaneous fore- and hindlimb contacts. As speed increases, hindlimbs continue to vault, while forelimbs show a single-humped force profile indicating a bouncing mode (Figure 6B). At the theoretical limit for vaulting in hindlimbs (UH′=1), hindlimbs also shift to bouncing (Figure 6C) (see Supplementary Video S1 for animations of these solutions). This general gait shift is also observed at the lowest force-rate penalty (Figures 6D–F), although peak forces approach impulsivity, as expected from work-minimizing optimization (Srinivasan, 2010). At walking speeds, solutions may include periods during stance where hindlimbs are completely offloaded (Figure 6D).

FIGURE 6

FIGURE 6. Predicted ground reaction forces from simulation for the unconstrained Batrachotomus model with a force-rate penalty of 3×10−3 (upper row) and 3×10−5 (lower row). (A) At slow speeds, a walking trot pattern is observed, with double-humped profiles typical of vaulting. (B) At intermediate speeds, the forelimbs transition to a single-humped, bouncing mode. (C) At the fastest speeds, the hindlimbs also transition to bouncing. (D–F) Similar behavior is also seen at a higher force-rate penalty. However, the extreme peak forces and the unloading of midstance force at some speeds (D) make this force-rate penalty unrealistic (see Supplementary Video S1 for animations).

When solutions are constrained to match fossil trackway track phase trends, ground reaction forces differ somewhat from the unconstrained case. Before transitioning to a constant track phase, the optimal solution moves away from a vaulting walking trot and shows vaulting hindlimbs with skewed ground reaction forces in forelimbs, indicating an asymmetrical (generative) bouncing mode (Figure 7A, see also Supplementary Video S2). This gait persists at the transition to the constant track phase (Figure 7B), but gradually shifts to bouncing in both fore- and hindlimbs, similar to the unconstrained scenario (Figure 7C). As speed further increases, the solution remains the same but with lower duty factor and higher peak forces.

FIGURE 7

FIGURE 7. Predicted ground reaction forces for the Batrachotomus model constrained to match the empirical track phase. (A) By a speed of 0.49, the optimal solution is to use skewed ground reaction forces in the forelimbs, with semi-vaulting forces in the hindlimbs. (B) This pattern is preserved at the transition point where the track phase remains constant with increasing speed. (C) By a speed of 0.80, the solution shifts to a running tölt, similar to the unconstrained case but differing in the timing of forelimb contact. The same solution is found at faster speeds in the constrained case, but with lower duty factor and higher peak forces (see Supplementary Video S2 for animations).

Constrained solutions exhibit higher costs than unconstrained solutions (Supplementary Figure S2A). The cost difference is greatest at intermediate speeds and diminishes at faster speeds. At UH′=0.55, the cost of transport in the constrained case is 1.2 times that of the unconstrained case (Supplementary Figure S2B). At UH′=1.92, this ratio decreases to 1.01.

Discussion

The simulation method accurately predicts canine track phase within natural variation, although predicted values are consistently slightly below mean empirical values (Figure 3). The model correctly predicts symmetrical walking and running gaits in dogs, the shape of their ground reaction forces (Figure 4), and the gait transition speed. This validation lends confidence to applying the model to extinct forms where only stride length, size, and shape can be estimated, and gait is unknown.

Brachychirotherium trackways demonstrate a consistent pattern of track phase and speed: a sharp reduction with increasing speed below UH′=0.6, followed by a constant track phase up to UH′=1, where the track phase suddenly drops (Figure 5). Isochirotherium trackways also follow this pattern, although data above dimensionless speeds of 0.8 are lacking. This overall similarity in track phase pattern with estimated speed justifies combining these ichnogenera for analysis.

Across all force-rate penalties, simulations accurately predict a walking trot at slow speeds, closely following the analytical curve. In every case, the optimal gait transitions around UH′=0.4, shifting to a higher track phase. This indicates not only an increase in limb phase from a trot to a diagonal sequence gait but also a fundamental shift in gait type. While ground reaction force profiles at slow speeds show the double-humped shape characteristic of vaulting (Figures 6A,D), the faster gait is a hybrid, with vaulting hindlimbs and bouncing forelimbs (Figures 6B,E). This closely resembles the slow tölt of Icelandic horses (Biknevicius et al., 2004). Similar to Icelandic horses, simulations switch to a “running tölt” at higher speeds: a four-beat symmetrical gait with single-humped ground reaction force profiles in all limbs (Figure 6C). The tölt is an uncommon gait in mammals (Vincelette, 2021) and unheard of in archosaurs, though it has been identified in fossil horse trackways (Renders, 1984; Vincelette, 2021).

However, at speeds above 0.4, simulations diverge significantly from fossil trackways in track phase. Despite this, trackways show distinct changes in track phase around UH′=0.6 and 1.0, coinciding with gait changes in simulations. When simulations are constrained to match fossil trackway track phase, the solution remains qualitatively similar to the unconstrained case, showing bouncing forelimbs and vaulting hindlimbs at UH′=0.6 (Figure 7)—akin to a slow tölt—before transitioning to a bouncing mode in both limbs at UH′=1—similar to a fast tölt. The marked shifts in fossil track phase at UH′=0.6 and 1.0, their agreement with limb phase changes according to analytical relations, and multiple simulations predicting gait transitions near these speeds, suggest that these fossil data demonstrate a gait transition in pseudosuchian trackmakers.

Although fossil trackways show manus placed cranially to the ipsilateral pes in a couplet, qualitatively similar to modern crocodylians in a walking trot (Kubo, 2008), the long trackway stride lengths suggest gaits more like a dissociated trot or diagonal sequence. Modern crocodiles, the closest living relatives of Batrachotomus, do not typically transition to a four-beat gait at higher speeds, instead continuing to trot or shifting to asymmetrical gaits (Hutchinson et al., 2019). While extant crocodiles do exhibit an increase in limb phase with increasing speed for symmetrical gaits (Supplementary Figure S3), this change is much more gradual than observed here. Crocodiles do not consistently walk with the lateral sequence diagonal-couplet gait (Supplementary Figure S3; Hutchinson et al., 2019) considered ancestral for quadrupedal gnathostomes (Wimberly et al., 2021). These results provide the first evidence that extinct pseudosuchians exhibited different gaits than their modern crocodile relatives and the first indication of a gait transition in an extinct pseudosuchian lineage.

The use of a two-beat gait at slow speeds and a four-beat gait at faster speeds aligns with Polet’s (2021b) analysis. Batrachotomus‘s large pitch moment of inertia relative to its glenoacetabular distance gives it a Murphy number of 3. Above a Murphy number of 1, a four-beat run becomes optimal because the energetic cost of pitching the body is lower than the energetic cost of vertical body movement. Thus, rejecting pitching via a trotting gait becomes energetically inefficient. However, maintaining vaulting in a typical four-beat walk necessitates body pitching, which is energetically costly for animals with a large pitch moment of inertia. This explains why a walking trot is favored at lower speeds.

Both unconstrained and constrained cases show similar ground reaction force solutions, but they are skewed in the latter. In the unconstrained case, the forelimb is nearly vertical when hindlimbs are in double support (Figure 8A). By peaking force at midstance, it effectively offloads body weight during the energetically costly step transition for hindlimbs (Schroeder and Bertram, 2018). Simultaneously, the symmetrical, single-hump profile acts as a distributed pseudo-elastic “collision” (Figure 6B), minimizing limb work while managing force-rate penalty (Ruina et al., 2005; Rebula and Kuo, 2015).

FIGURE 8

FIGURE 8. Geometry at hindlimb step transition for the unconstrained and constrained track phase cases, both at UH′=0.49 and c′=0.003. (A) In the unconstrained case, the forelimb is nearly vertical, allowing the hindlimbs to be effectively offloaded. The resulting ground reaction forces (GRF) are symmetrical, as shown in Figure 6B. (B) In the constrained track phase case, the shoulder is extended, so will provide a forward as well as vertical propulsive force. It can assist the hindlimbs pushoff in this position. GRF forces become asymmetrical, as shown in Figure 7A.

In the constrained case, the shoulder is flexed during double support (Figure 8A), meaning that pushing forces from the leg generate both vertical and forward propulsion of the center of mass. This is less effective for weight offloading during support transfer but contributes to pre-transfer hindlimb pushoff, mitigating work-related energetic losses (Ruina et al., 2005; Rebula and Kuo, 2015; Schroeder and Bertram, 2018). Consequently, forelimb force can increase, while the second peak in hindlimbs can decrease (Figure 7A). However, the asymmetry results in a generative (plastic) distributed “collision,” which typically requires more work than a symmetrical (pseudo-elastic) collision (Ruina et al., 2005).

Trackway transition away from the analytical walking trot line occurs around UH′=0.6 (Figure 5), well below the maximum pendular walk speed of UH′=1 (Usherwood, 2005), but matching the four-beat gait transition predicted by Polet (2021b) for a Murphy number of 3 in a perfectly symmetrical model (center of mass at midpoint of glenoacetabular distance, equal leg lengths to glenoacetabular distance).

At the inferred gait transition in trackway data, ipsilateral manus and pes prints are nearly overstepping. Increasing speed without gait change would lead to overstepping and ipsilateral manus and pes collision, unless limb orientations changed. Could this inferred gait transition be driven by this physical constraint, rather than energetic considerations?

Modern crocodiles avoid foot collision during walking trots by yawing the body, misaligning the craniocaudal axis with the motion direction. This places manus prints slightly to the left or right of pes prints (Kubo, 2008; see Figures 2A,E therein). Dogs also employ this strategy when trotting (Murie and Elbroch, 2005). There’s no a priori reason to assume “rauisuchians” like Batrachotomus couldn’t yaw their bodies similarly to continue a walking trot at higher speeds. Moreover, the planar model used here is not constrained to prevent ipsilateral leg or foot collisions. Thus, the transition in this model is purely driven by energetic factors.

The earlier trot transition in simulations (around UH′= 0.40) appears driven by Batrachotomus‘s relatively short forelimbs (61% of hindlimb length). A 10% increase in model forelimb length raises the transition speed from 0.40 to 0.45, while a 50% increase shifts it to 0.49 (Supplementary Figures S4, 5), also decreasing track phase value at transition speed. This may reflect morphological differences between actual trackmakers and Batrachotomus. The reconstruction has a manus to pes length ratio of 0.58, compared to 0.35–0.38 in trackways. This aligns with fossil footprint morphology, showing digitigrade or semi-digitigrade manus prints (Diedrich, 2015; Klein and Lucas, 2021), roughly matching modern crocodiles (Hutson and Hutson, 2015), while Batrachotomus is considered plantigrade. Alternatively, Batrachotomus may have had a less flexed elbow in life, increasing effective forelimb length (Figure 2).

This is possibly reflected in the ratio between estimated horizontal glenoacetabular distance and pes length (LBx/LP) in Brachychirotherium trackways (2.95–3.11), which better matches the Batrachotomus reconstruction using absolute glenoacetabular distance (LB/LP= 3.08) rather than LBx/LP (2.85). This might result from glenoid and acetabulum being at more equal height than assumed, or from morphological differences between Batrachotomus and Brachychirotherium, or uncertainties in the Batrachotomus pedal reconstruction.

While simulations provide evidence of gait transition in trackmakers, they don’t accurately predict track phase except at slow speeds. Reasons for this discrepancy may include: model inaccuracies in capturing “rauisuchian” gait energetics (e.g., neglecting leg inertia or muscle force–velocity characteristics); trackmakers not following Alexander’s (1976) stride length-speed relationship (primarily based on mammals), possibly due to reduced hip flexion/extension in some “rauisuchians” (Nesbitt et al., 2013); trackmaker morphology differing from Batrachotomus; or energetics not being primary gait determinants. The soft substrate of track formation could also influence gait choice and phase relationships. Future pseudosuchian locomotion simulation developments can address these issues by enhancing realism and validating models with extant crocodiles, improving our understanding of archosaur vs crocodile locomotion.

Conclusion

This study applied a planar, generalized quadrupedal model to the gait of Batrachotomus kupferzellensis, an extinct crocodile-line (pseudosuchian) archosaur. Predictions were compared to fossil trackways likely left by close relatives of Batrachotomus. Optimized to minimize leg work and squared force rate, the model correctly predicted a sharp track phase reduction with speed, indicating a trot at low speeds. Subsequently, the model predicted a transition to a four-beat walk similar to a slow tölt, near where fossil trackways diverged from the walking trot trajectory and appeared to transition to a diagonal sequence gait. Finally, when fossil trackways showed another sharp track phase transition, the model predicted a transition to a four-beat gait similar to a fast tölt. This provides the first evidence of gait transition in an extinct pseudosuchian and suggests that “rauisuchians” like Batrachotomus may have exhibited gaits distinct from modern crocodiles.

Given Batrachotomus‘s inferred features shared with both modern crocodiles and mammals, trajectory optimization offers a unique approach to understanding gait where no direct analogue exists. Optimization results suggest that Batrachotomus‘s large pitch moment of inertia and erect limb posture favored a tölt-like gait, unseen in any archosaurian group today and rare in mammals. This raises intriguing questions about when and how often this gait suite evolved in pseudosuchians, and the ancestral state for Archosauria (birds, crocodiles, and all extinct descendants of their common ancestor, including Mesozoic dinosaurs). More sophisticated 3D models incorporating lateral motions and realistic morphology (e.g., Bishop et al., 2021), or neuromuscular control and stability analyses, may yield further insights into archosaur locomotion compared to crocodiles and other tetrapods.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The project was conceived by DP and JH, and both authors gathered data from the literature and wrote the manuscript. DP digitized trackways, analyzed data, and performed the simulations.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Research Council Advanced Investigator Award (Grant agreement ID: 695517) to JH.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashleigh Wiseman for her prior helpful discussions. We also thank Vivian Allen, Andrew Cuff and Peter Bishop for preparing the Batrachotomus model, as well as Eudald Mujal and Shinya Aoi for their thoughtful reviews, which greatly enhanced the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2021.800311/full#supplementary-material

References

Alexander, R. M. (1976). Estimates of Speeds of Dinosaurs. Nature 261, 129–130. doi:10.1038/261129a0 | Google Scholar

Apesteguía, S., Riguetti, F., Citton, P., Veiga, G. D., Poiré, D. G., de Valais, S., et al. (2021). The Ruditayoj-Tunasniyoj Fossil Area (Chuquisaca, Bolivia): a Triassic Chirotheriid Megatracksite and Reinterpretation of Purported Thyreophoran Tracks. Hist. Biol. 33, 2883–2896. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1833328 | Google Scholar

Bertram, J. E. A., Lee, D. V., Case, H. N., and Todhunter, R. J. (2000). Comparison of the Trotting Gaits of Labrador Retrievers and Greyhounds. Am. J. Vet. Res. 61, 832–838. doi:10.2460/ajvr.2000.61.832 | Google Scholar

Biknevicius, A. R., Mullineaux, D. R., and Clayton, H. M. (2004). Ground Reaction Forces and Limb Function in Tölting Icelandic Horses. Equine Vet. J. 36, 743–747. doi:10.2746/0425164044848190 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bishop, P. J., Bates, K. T., Allen, V. R., Henderson, D. M., Randau, M., and Hutchinson, J. R. (2020). Relationships of Mass Properties and Body Proportions to Locomotor Habit in Terrestrial Archosauria. Paleobiology 46, 550–568. doi:10.1017/pab.2020.47 | Google Scholar

Bishop, P. J., Falisse, A., De Groote, F., and Hutchinson, J. R. (2021). Predictive Simulations of Running Gait Reveal a Critical Dynamic Role for the Tail in Bipedal Dinosaur Locomotion. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7348. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi7348 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bonaparte, J. F. (1984). Locomotion in Rauisuchid Thecodonts. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 3, 210–218. doi:10.1080/02724634.1984.10011976 | Google Scholar

Clark, N. D. L., Aspen, P., and Corrance, H. (2002). Chirotherium barthii Kaup 1835 from the Triassic of the Isle of Arran, Scotland. Scottish J. Geology. 38, 83–92. doi:10.1144/sjg38020083 | Google Scholar

Clark, N. D. L., and Corrance, H. (2009). New Discoveries of Isochirotherium herculis (Egerton 1838) and a Reassessment of Chirotheriid Footprints from the Triassic of the Isle of Arran, Scotland. Scottish J. Geology. 45, 69–82. doi:10.1144/0036-9276/01-362 | Google Scholar

Diedrich, C. (2015). Isochirotherium Trackways, Their Possible Trackmakers (?Arizonasaurus): Intercontinental Giant Archosaur Migrations in the Middle Triassic Tsunami-Influenced Carbonate Intertidal Mud Flats of the European Germanic Basin. Carbonates Evaporites 30, 229–252. doi:10.1007/s13146-014-0228-z | Google Scholar

Diedrich, C. (2012). Middle Triassic Chirotherid Trackways on Earthquake Influenced Intertidal Limulid Reproduction Flats of the European Germanic Basin Coasts. Cent. Eur. J. Geo. 4, 495–529. doi:10.2478/s13533-011-0080-9 | Google Scholar

Gill, P. E., Murray, W., and Saunders, M. A. (2005). SNOPT: An SQP Algorithm for Large-Scale Constrained Optimization. SIAM Rev. 47, 99–131. doi:10.1137/s0036144504446096 | Google Scholar

Gower, D. J., and Schoch, R. R. (2009). Postcranial Anatomy of the Rauisuchian archosaur Batrachotomus kupferzellensis. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 29, 103–122. doi:10.1080/02724634.2009.10010365 | Google Scholar

Griffin, T. M., Main, R. P., and Farley, C. T. (2004). Biomechanics of Quadrupedal Walking: How Do Four-Legged Animals Achieve Inverted Pendulum-like Movements? J. Exp. Biol. 207 (2072), 3545–3558. doi:10.1242/jeb.01177 | Google Scholar

Henderson, D. M. (2003). Effects of Stomach Stones on the Buoyancy and Equilibrium of a Floating Crocodilian: a Computational Analysis. Can. J. Zool. 81, 1346–1357. doi:10.1139/z03-122 | Google Scholar

Hminna, A., Klein, H., Zouheir, T., Lagnaoui, A., Saber, H., Lallensack, J. N., et al. (2021). The Late Triassic Archosaur Ichnogenus Brachychirotherium: First Complete Step Cycles from Morocco, North Africa, with Implications for Trackmaker Identification and Ichnotaxonomy. Hist. Biol. 33, 723–736. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1658097 | Google Scholar

Hutchinson, J. R., Felkler, D., Houston, K., Chang, Y.-M., Brueggen, J., Kledzik, D., et al. (2019). Divergent Evolution of Terrestrial Locomotor Abilities in Extant Crocodylia. Sci. Rep. 9, 19302. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55768-6 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hutson, J. D., and Hutson, K. N. (2015). Inferring the Prevalence and Function of finger Hyperextension in Archosauria from finger‐joint Range of Motion in the American alligator. J. Zool 296, 189–199. doi:10.1111/jzo.12232 | Google Scholar

Jayes, A. S., and Alexander, R. M. (1978). Mechanics of Locomotion of Dogs (Canis familiaris) and Sheep (Ovis aries). J. Zoolog. 185, 289–308. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1978.tb03334.x | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kubo, T. (2008). In Quest of the Pteraichnus Trackmaker: Comparisons to Modern Crocodilians. Acta Palaeontologica Pol. 53, 405–412. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0304 | Google Scholar

Maes, L. D., Herbin, M., Hackert, R., Bels, V. L., and Abourachid, A. (2008). Steady Locomotion in Dogs: Temporal and Associated Spatial Coordination Patterns and the Effect of Speed. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 138–149. doi:10.1242/jeb.008243 | Google Scholar

Nesbitt, S. J., Brusatte, S. L., Desojo, J. B., Liparini, A., De França, M. A. G., Weinbaum, J. C., et al. (2013). Rauisuchia. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publications 379 (1), 241–274. doi:10.1144/SP379.1 | Google Scholar

Nyakatura, J. A., Melo, K., Horvat, T., Karakasiliotis, K., Allen, V. R., Andikfar, A., et al. (2019). Reverse-engineering the Locomotion of a Stem Amniote. Nature 565, 351–355. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0851-2 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Patterson, M. A., and Rao, A. V. (2014). GPOPS-II. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 41, 1–37. doi:10.1145/2558904 | Google Scholar

Petti, F. M., Avanzini, M., Nicosia, U., Girardi, S., Bernardi, M., Ferretti, P., et al. (2009). Late Triassic (Early-middle Carnian) Chirotherian Tracks from the Val Sabbia Sandstone (Eastern Lombardy, Brescian Prealps, Northern Italy). Riv. Ital. di Paleontol. e Stratigr. 115, 277–290. doi:10.13130/2039-4942/6384 | Google Scholar

Polet, D. T., and Bertram, J. E. A. (2019). An Inelastic Quadrupedal Model Discovers Four-Beat Walking, Two-Beat Running, and Pseudo-elastic Actuation as Energetically Optimal. PLOS Comput. Biol. 15, e1007444. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007444 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Polet, D. T. (2021a). Delyle/Optimize-Symmetrical-Quadruped: Optimize Symmetrical Quadruped. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5593594 | Google Scholar

Polet, D. T. (2021b). The Murphy Number: How Pitch Moment of Inertia Dictates Quadrupedal Walking and Running Energetics. J. Exp. Biol. 224, jeb228296. doi:10.1242/jeb.228296 | Google Scholar

Rebula, J. R., and Kuo, A. D. (2015). The Cost of Leg Forces in Bipedal Locomotion: A Simple Optimization Study. PLOS ONE 10, e0117384. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117384 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Renders, E. (1984). The Gait of Hipparion Sp. From Fossil Footprints in Laetoli, Tanzania. Nature 308, 179–181. doi:10.1038/308179a0 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ruina, A., Bertram, J. E. A., and Srinivasan, M. (2005). A Collisional Model of the Energetic Cost of Support Work Qualitatively Explains Leg Sequencing in Walking and Galloping, Pseudo-elastic Leg Behavior in Running and the Walk-To-Run Transition. J. Theor. Biol. 237, 170–192. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.04.004 | Google Scholar

Schroeder, R. T., and Bertram, J. E. (2018). Minimally Actuated Walking: Identifying Core Challenges to Economical Legged Locomotion Reveals Novel Solutions. Front. Robot. AI 5, 58. doi:10.3389/frobt.2018.00058 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Srinivasan, M. (2010). Fifteen Observations on the Structure of Energy-Minimizing Gaits in many Simple Biped Models. J. R. Soc. Interf. 8, 74–98. doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0544 | Google Scholar

Usherwood, J. R. (2020). An Extension to the Collisional Model of the Energetic Cost of Support Qualitatively Explains Trotting and the Trot-Canter Transition. J. Exp. Zool. 333, 9–19. doi:10.1002/jez.2268 | Google Scholar

Usherwood, J. R. (2005). Why Not Walk Faster? Biol. Lett. 1, 338–341. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0312 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Vincelette, A. (2021). Determining the Gait of Miocene, Pliocene, and Pleistocene Horses from Fossilized Trackways. Foss. Rec. 24, 151–169. doi:10.5194/fr-24-151-2021 | Google Scholar

Willey, J. S., Biknevicius, A. R., Reilly, S. M., and Earls, K. D. (2004). The Tale of the Tail: Limb Function and Locomotor Mechanics in Alligator mississippiensis. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 553–563. doi:10.1242/jeb.00774 | Google Scholar

Wimberly, A. N., Slater, G. J., and Granatosky, M. C. (2021). Evolutionary History of Quadrupedal Walking Gaits Shows Mammalian Release from Locomotor Constraint. Proc. R. Soc. B. 288, 20210937. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.0937 | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xi, W., Yesilevskiy, Y., and Remy, C. D. (2016). Selecting Gaits for Economical Locomotion of Legged Robots. Int. J. Robotics Res. 35, 1140–1154. doi:10.1177/0278364915612572 | Google Scholar

Yesilevskiy, Y., Yang, W., and Remy, C. D. (2018). Spine Morphology and Energetics: How Principles from Nature Apply to Robotics. Bioinspir. Biomim. 13, 036002. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/aaaa9e | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: locomotion, predictive simulation, Pseudosuchia, fossil trackways, energetics, Chirotheriidae

Citation: Polet DT and Hutchinson JR (2022) Estimating Gaits of an Ancient Crocodile-Line Archosaur Through Trajectory Optimization, With Comparison to Fossil Trackways. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9:800311. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.800311

Received: 22 October 2021; Accepted: 30 December 2021;Published: 03 February 2022.

Edited by:

Bernardo Innocenti, Université libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

Reviewed by:

Eudald Mujal, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, GermanyShinya Aoi, Kyoto University, Japan

Copyright © 2022 Polet and Hutchinson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Delyle T. Polet, ZHBvbGV0QHJ2Yy5hYy51aw==; John R. Hutchinson, amh1dGNoaW5zb25AcnZjLmFjLnVr

†ORCID: Delyle T. Polet, orcid.org/0000-0002-8299-3434; John R. Hutchinson, orcid.org/0000-0002-6767-7038