A Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial For Preventing Type 2 Diabetes offers insights into practical diabetes prevention strategies. At COMPARE.EDU.VN, we understand the importance of accessing reliable information to make informed decisions about your health and wellness; this article explores a study evaluating a YMCA-based Diabetes Prevention Program, offering valuable perspectives on preventing diabetes. Explore practical diabetes prevention, lifestyle interventions, and diabetes risk reduction strategies.

1. Understanding the Need for Diabetes Prevention

More than 150 million Americans are grappling with being overweight or obese, setting the stage for weight-related health complications such as heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, abnormal blood cholesterol, and diabetes. The potential to prevent or reverse obesity offers a beacon of hope, promising to alleviate these complications and reduce the associated healthcare costs. The U.S. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) spotlighted how resource-intensive lifestyle changes, focusing on daily physical activity and modest weight loss, could halve the rate of type 2 diabetes development. However, sustaining even modest weight loss poses a significant challenge, especially for younger individuals, those with higher obesity levels, minorities, and people from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. The financial burden of offering these intensive programs also presents a hurdle to their widespread adoption. While studies like the DPP have confirmed the effectiveness and safety of lifestyle interventions in preventing diabetes, few high-quality or well-controlled studies have assessed the impact of similar interventions in broader clinical or community settings. This gap underscores the necessity for accessible, cost-effective preventive measures, highlighting the importance of programs like the YMCA’s approach to diabetes prevention.

2. The RAPID Study: A Community-Based Approach

To fill this critical research void, the Reaching Out to Prevent Increases in Diabetes (RAPID) study adopted a randomized effectiveness trial design. This trial aimed to assess a collaborative strategy that links health systems in identifying prediabetes patients with the community-based delivery of a more affordable, group-centered lifestyle intervention offered by the YMCA. The core objective was to determine whether the YMCA model for translating the DPP intervention (YDPP) could effectively reach a large, diverse population, primarily from low-income backgrounds, who were at risk for prediabetes. Furthermore, the study sought to compare the effectiveness of YDPP against the standard of care in achieving modest weight losses, which have been previously linked to a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This research represents a significant step forward in identifying practical, scalable interventions for diabetes prevention in real-world settings.

3. Methods Used in the RAPID Trial

The RAPID trial employed a two-arm comparative effectiveness design, randomizing participants in a 1:1 ratio to either:

- Active encouragement to participate in a free, group-based adaptation of the DPP lifestyle intervention offered by the YMCA (YDPP arm).

- Receipt of standard clinical care, supplemented by brief counseling and information on available community resources for lifestyle modification (standard care arm).

3.1 Participant Selection

The trial enrolled adults aged 18 years or older with a body mass index (BMI) of 24 or greater, who had not been previously diagnosed with diabetes. Participants also had to exhibit at least one blood test indicating a high risk for type 2 diabetes, such as a fasting plasma glucose level of 100–125 mg/dL, a 2-hour postload plasma glucose level of 140–199 mg/dL, or an HbA1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 5.7%–6.9%. Exclusion criteria were put in place to ensure participant safety and data integrity, including an inability to provide informed consent, lack of English literacy, pregnancy or plans for pregnancy, active use of medications known to alter glucose metabolism, blood pressure readings of 180/105 millimeters of mercury or higher, or a comorbidity expected to limit life expectancy to less than three years.

3.2 Recruitment Process

Clinical data managers at nine urban primary care clinics in Indianapolis, Indiana, used electronic databases to pinpoint patients who met the inclusion criteria and had completed a blood test indicating prediabetes within the previous 12 months. After securing permission from the primary care providers to approach their patients, research assistants contacted and prescreened each patient over the phone. Interested patients were invited to a face-to-face meeting with a research assistant to receive additional information about preventing type 2 diabetes. All patients attending this meeting, confirmed as eligible, and providing written informed consent were enrolled in the study.

3.3 Intervention Components

At enrollment, participants in both study arms received information and encouragement to utilize local community resources and self-help diabetes prevention materials from the National Diabetes Education Program. This information was reinforced at each study visit. Additionally, research assistants encouraged and assisted participants in both arms to schedule a visit with a registered dietitian at the clinic to create an action plan for dietary changes and weight loss. These components, common to both study arms, aligned with published recommendations for adults with prediabetes and were considered more intensive than the support levels typically offered in primary care settings. Participants randomized to the standard care arm received only these intervention components, enabling the evaluation of the comparative effectiveness of standard care versus standard care in conjunction with free access to YDPP.

3.4 The YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program (YDPP)

Within 24 hours of enrollment, the YMCA intervention coordinator received the name and contact information for each new participant randomized to the YDPP arm. The coordinator contacted each participant and offered the opportunity to take part in the YDPP lifestyle intervention free of charge. While active participation was encouraged, it was not mandatory. Interested participants were grouped into cohorts of 8 to 12 persons to meet at mutually convenient times and locations, including both YMCA and non-YMCA facilities. The YDPP adaptation involved setting goals, self-monitoring, and employing participant-centered problem-solving strategies to achieve modest weight loss (5%–7% reduction from baseline). This was pursued through a combination of moderate physical activity (150 minutes per week, equivalent to walking) and reduced dietary fat and calorie consumption. The intervention began with 16 face-to-face, small-group lessons, each lasting 60 to 90 minutes, delivered over 16 to 24 weeks, followed by monthly support meetings lasting about 60 minutes for the duration of the trial. Participants were also provided with tools such as step counters, measuring cups, food scales, fat and calorie tracking tools, and recipe guides. YMCA leadership selected and hired YDPP instructors, who underwent an initial two-day training program, as well as annual refresher training, to ensure core intervention competencies. The YMCA intervention coordinator supervised all instructors and monitored program fidelity and quality assurance.

3.5 Data Collection and Outcomes

Research assistants collected data at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months via written surveys, biometric assessments, and finger-stick blood tests. The primary outcome was the change in body weight over 12 months. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of participants achieving weight loss goals of 5% or greater, as well as changes in blood pressure, total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, and glycated hemoglobin (A1c). Blood pressures were assessed as the mean of two values taken at rest in a seated position. A1c was assessed from a finger-stick capillary blood sample using a DCA 2000/Vantage portable bench-top analyzer. Non-fasting cholesterol concentrations were measured from capillary blood using an LDX lipid analyzer. Survey data collected at each visit was used to assess potential unanticipated harms and secondary clinical outcomes such as cardiovascular events.

3.6 Randomization and Blinding

Randomization lists were computer-generated separately for each clinic site using a 1:1 allocation with blocks of 2. Intervention assignment was blinded to research staff using individually sealed opaque envelopes. Participants were not informed that the study involved randomization but were told they would receive repeat diabetes risk testing and other risk factor assessments, brief lifestyle counseling, and ongoing updates about community-based lifestyle intervention resources. While participants could not be blinded to the specific resources they were offered, they remained unaware that their resources might differ from those of other study participants.

4. Statistical Analysis Methods

The encouragement trial design facilitated the observation of YDPP participation levels in a real-world setting and enabled two primary statistical analyses:

- An assessment of overall, intent-to-treat (ITT) effects, irrespective of YDPP participation.

- Valid estimation of the average treatment effect among compliers.

In the ITT analysis, repeated outcome measures were analyzed using longitudinal linear regression (continuous outcomes) or logistic regression (dichotomous 5% weight loss), treating the participant as a random effect and using robust variance estimates. Regression models included three observations per participant (at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). Multivariable regression models were estimated using multiple imputation to account for loss to follow-up among some trial participants. Missing weight data were estimated using the predictive mean matching imputation method, drawing imputed values from the five nearest neighbor observations within the same study arm that had the most similar covariate distributions, including gender, annual household income, race/ethnicity, age, intervention session attendance, baseline weight, study month, and clinic. Differential intervention effects at 6 months were estimated through a group-by-time interaction term. The primary independent variable was the 12-month effect of random treatment assignment (YDPP or standard care). After model estimation, adjusted weight change and adjusted probability of 5% weight loss were predicted using the “mi predict” command in Stata version 12.1. Preplanned ITT subgroup analyses assessed adjusted, predicted weight changes among both African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Exploratory ITT analysis tested differences in weight changes between these two subgroups by introducing a race-by-treatment interaction term. Due to the encouragement trial design, a sizeable proportion of participants assigned to YDPP was expected not to participate. To estimate YDPP program effectiveness among those who chose to attend, a two-stage generalized least squares instrumental variables approach was used for all continuous outcomes. This method relies on an instrument associated with receiving treatment (i.e., sufficient participation in YDPP) but has no independent effect on outcomes except through that treatment. In this analysis with instrumental variable models, a dichotomous indicator for YDPP participation (≥ 9 visits to YDPP within 12 months) was used as the exposure of interest, random treatment assignment (YDPP or standard care) as the instrumental variable, and the same covariates and interaction terms used in the ITT analysis. Attendance in 9 or more lessons was used to define a meaningful DPP dose, based on previous studies. Random treatment assignment was considered a strong instrumental variable due to its strong association with intervention attendance and lack of other direct or indirect relationships with health outcomes, except through attendance. In the first stage of the regression, random treatment assignment was used to predict the probability of completing 9 or more visits. In the second stage, predicted values from the first stage were used to estimate the outcome. Instrumental variable analyses included the same covariates as ITT models and used all available weight data, assuming data were missing at random. Overall, this method is considered a strong quasi-experimental research design to reduce the threat of selection bias in analyses of treatment compliers. A targeted sample size of 203 participants was expected to provide more than 80% power at the α = 0.05 significance level to detect an absolute between-group mean difference in the percentage weight loss at 12 months as low as 2.2% (SD = 4.3%). All analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 12.1.

5. Key Findings from the RAPID Study

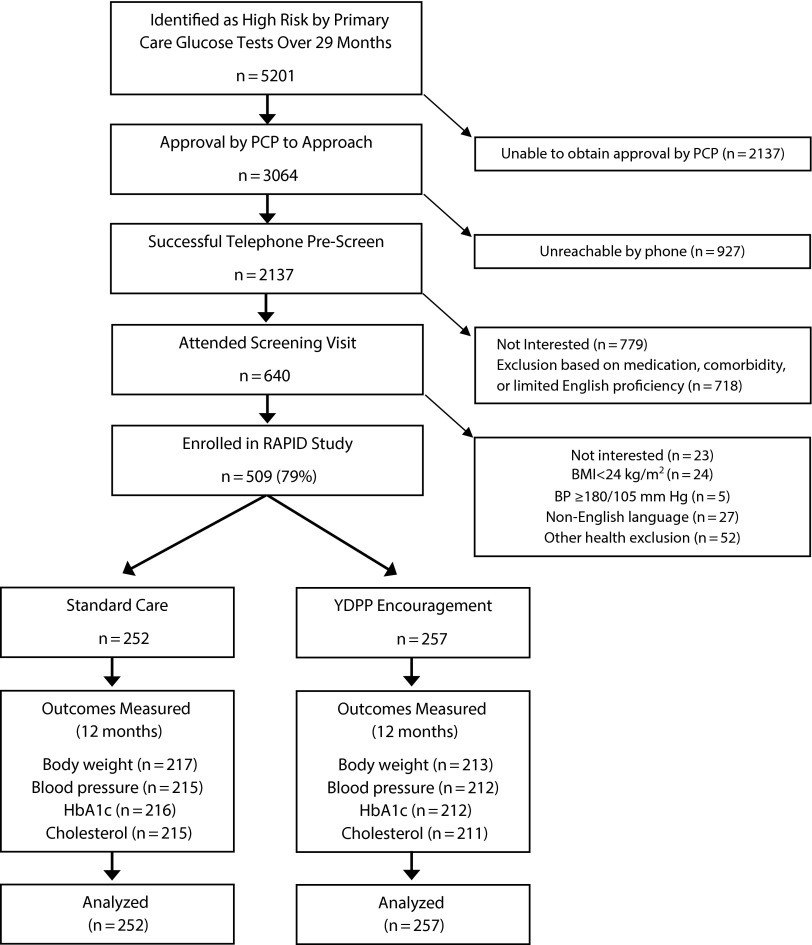

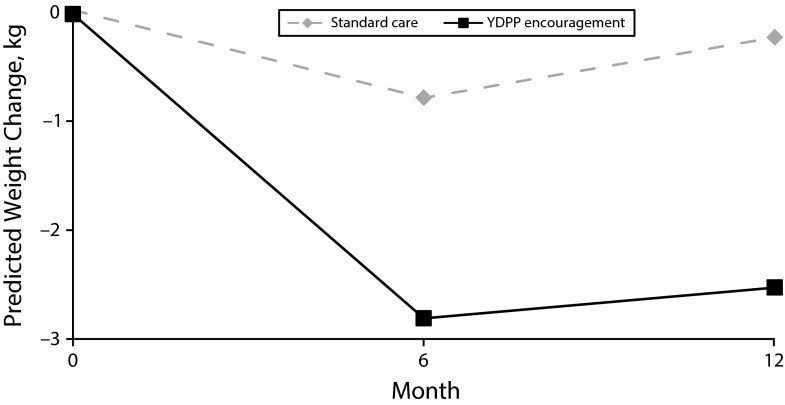

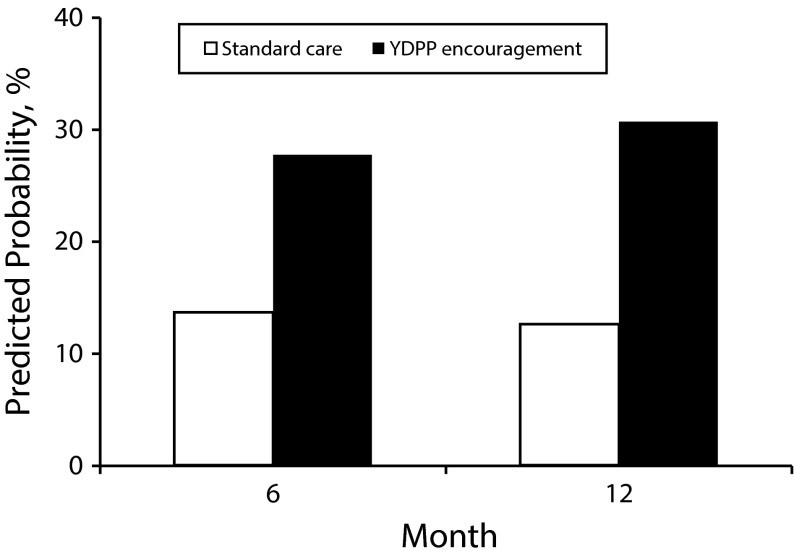

Over a 29-month recruitment period, 3064 patients were screened, and 509 were found eligible and enrolled, representing about 43% of all eligible patients approached. Of those enrolled, 257 participants (50.5%) were randomized to the YDPP arm, and 252 (49.5%) to the standard care arm. The participant demographic reflected a wide age range and high mean baseline BMI (36.8 kg/m2); the cohort was predominantly women (70.7%) and African American (57.0%), with 61.3% reporting household incomes less than $25,000. Cardiovascular risk factors were modestly elevated, with many participants reporting medication use (e.g., 60.5% were taking a blood pressure medication). Compared to non-Hispanic White participants, African Americans were younger, more often women, and reported lower income levels. There was no statistically significant difference in baseline BMI between African American and White participants. Among participants in the YDPP arm, 62.6% attended at least one lesson, and 40.0% completed nine or more intervention lessons, with a mean attendance of 9.5 visits. Participants who completed at least one intervention lesson were more likely to have a family history of diabetes. Similar percentages of non-Hispanic Whites (42.9%) and African Americans (39.5%) completed nine or more YDPP visits. In adjusted intention-to-treat analysis, those assigned to YDPP achieved a 2.3-kilogram greater weight loss at 12 months than did those assigned to standard care. In instrumental variable analyses, YDPP participants completing nine or more lessons experienced a 5.3-kilogram greater weight loss than they would have if they had received standard care alone. Overall, a 5% or greater weight loss was achieved by 13.4% of standard care participants and 32.4% of YDPP participants. In ITT analysis, the adjusted odds of 5% or greater weight loss at 12 months was 3.1 times higher for YDPP than for standard care participants. ITT analysis of other cardiometabolic risk-related outcomes showed no statistically significant differences in A1c, systolic blood pressure, HDL-cholesterol, or total cholesterol at 12 months. Similarly, there were no significant differences in any of these clinical intermediate outcomes in instrumental variable analyses estimating intervention effects among participants who completed nine or more YDPP lessons. There were no statistically significant differences between treatment arms in percentages of participants reporting joint sprains or strains, muscle or joint aches, or self-reported cardiovascular events. After removing participants with an A1c of 6.5% or greater at baseline, 10.6% of standard care and 11.8% of YDPP participants developed type 2 diabetes through 12 months of follow-up, based solely on an A1c of 6.5% or greater. In adjusted ITT analyses, mean weight losses at 12 months were 2.1 kilograms for African Americans and 3.3 kilograms for non-Hispanic Whites. The test for a difference in weight changes between these two subgroups using a treatment-by-race interaction term was not statistically significant.

6. Visualizing the Impact: Figures from the Study

The RAPID study included several figures that visually represent the key findings.

6.1 Study Flow (Figure 1)

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of participants through the study, from initial screening to enrollment and randomization. It highlights the reasons for non-approach, ineligibility, and non-enrollment, providing a comprehensive view of the recruitment process.

6.2 Predicted Changes in Weight (Figure 2)

Figure 2 presents the predicted changes in weight among study participants. The graph compares participants randomized to standard care with those encouraged to participate in the YDPP intervention, with missing data imputed via multiple imputation. The adjusted effects of treatment assignment are predicted from multivariable longitudinal linear regression.

6.3 Predicted Probability of 5% Weight Loss (Figure 3)

Figure 3 shows the predicted probability of achieving a 5% weight loss among study participants. The analysis compares participants randomized to standard care with those encouraged to participate in the YDPP intervention, with missing data imputed via multiple imputation. The adjusted odds ratios comparing allocation to the YDPP encouragement with standard care are derived from multivariable longitudinal logistic regression.

7. Baseline Characteristics of the Randomized Cohort

The study cohort’s baseline characteristics provide critical context for interpreting the trial’s findings. Key demographics, health indicators, and socioeconomic factors were meticulously recorded to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the study population. These details help in assessing the applicability of the results to broader populations and in identifying potential factors that may influence the effectiveness of the intervention.

7.1 Key Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Overall, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Standard Care, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | YDPP Encouragement, No. (%) or Mean ±SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 509 | 252 | 257 |

| Age, y | 51.0 ±12.1 | 51.2 ±12.0 | 50.8 ±12.2 |

| Female | 360 (70.7) | 173 (68.7) | 187 (72.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 36.8 ±8.5 | 36.5 ±8.3 | 37.1 ±8.7 |

| Weight, kg | 102.4 ±25.5 | 101.7 ±25.4 | 103.0 ±25.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| African American | 290 (57.0) | 143 (56.7) | 147 (57.2) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 178 (35.0) | 87 (34.5) | 91 (35.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 16 (3.1) | 4 (1.6) | 12 (4.7) |

| Other or multirace | 11 (2.2) | 9 (3.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Don’t know or refuse to answer | 14 (2.7) | 9 (3.6) | 5 (1.9) |

| Household income, $ | |||

| < 10 000 | 137 (26.9) | 68 (27.0) | 69 (26.8) |

| 10 000–24 999 | 175 (34.4) | 80 (31.8) | 95 (37.0) |

| ≥ 25 000 | 110 (21.6) | 57 (22.6) | 53 (20.6) |

| Don’t know or refuse to answer | 87 (17.1) | 47 (18.6) | 40 (15.6) |

| Family history of diabetes | 290 (57.0) | 143 (56.8) | 147 (57.2) |

| A1c | 6.0 ±0.3 | 6.0 ±0.3 | 6.1 ±0.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 132.2 ±14.6 | 130.9 ±13.8 | 133.5 ±15.2 |

| HDL-C, mg/dl | 42.6 ±14.8 | 42.1 ±14.2 | 43.2 ±15.4 |

| Non–HDL-C, mg/dl | 143.1 ±39.5 | 142.4 ±39.6 | 143.8 ±39.5 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 185.8 ±40.0 | 184.5 ±39.7 | 187.0 ±40.3 |

Understanding these baseline characteristics allows for a more nuanced interpretation of the study’s outcomes and the potential for replicating the intervention’s success in similar populations.

8. Interpreting the Results and Their Implications

This large, community-based, comparative effectiveness trial reveals that adults at high risk for type 2 diabetes experience a 2.3-kilogram (approximately 5 lbs) reduction in mean body weight after 12 months when offered a lifestyle intervention adapted from the DPP and delivered by the YMCA. For every five individuals offered the intervention, about one additional person achieved and maintained a 5% or greater weight loss after 12 months. This modest yet meaningful weight loss should be considered in the context of varying intervention attendance levels, ranging from 40.0% of participants completing nine or more intervention visits to 37.4% who chose not to participate. Importantly, the intervention resulted in significant weight loss differences for both African Americans (2.1 kg) and non-Hispanic Whites (3.3 kg), indicating that the YMCA model for diabetes prevention is a promising platform for scaling the DPP lifestyle intervention to reach large segments of the US population. By using instrumental variables regression to minimize selection bias, YDPP participants who completed nine or more program visits achieved approximately a 5.3-kilogram (equivalent to 11.7 lbs) reduction in body weight at 12 months compared to those offered brief advice alone. This weight loss effect aligns with previous smaller and nonrandomized DPP translation studies but is slightly lower than that of large randomized efficacy studies such as the DPP trial and HELP-PD. However, RAPID participants had a higher baseline BMI and were more likely to be women, African American, or of low socioeconomic position compared to these prior randomized controlled trials. These differences are significant because weight loss is often more difficult to achieve among these subgroups. Despite enrolling a more challenging population, RAPID estimated the 12-month mean weight loss among intervention users to be 5.3 kilograms (5.3% of baseline body weight). While encouraging weight loss effects were observed in RAPID, the intensive lifestyle intervention was not associated with significantly better cardiovascular risk factor control at 12 months. A probable reason for this finding is that participants who lost weight may have been advised by their primary care providers to reduce their use of medications for cardiovascular risk factor control, thus attenuating the overall changes in these outcomes. Additionally, A1c and lipid outcomes were assessed using point-of-care testing equipment, which has higher variability than laboratory standards, potentially requiring a larger sample size to show minimally important outcome differences. Given that the observed weight losses in RAPID should be sufficient to translate into meaningful reductions in the development of type 2 diabetes, further research is needed to understand whether sustained, modest weight losses lead to fewer cardiovascular events, lower health care consumption, and improved quality of life for most community-dwelling adults with prediabetes.

9. Limitations of the RAPID Study

The RAPID study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. Firstly, the study’s duration was relatively short (12 months), which prevented the analysis of long-term weight maintenance or delayed clinical outcomes that might only manifest over longer periods. Secondly, while covariate-based imputations were conducted for intention-to-treat analyses, it is impossible to definitively ascertain whether these imputations accurately reflected true outcomes for the modest number of participants (15.5%) with missing data at 12 months. Thirdly, although the use of random treatment assignment as an instrumental variable is considered a robust nonrandomized comparative effectiveness design, residual selection bias could still have influenced the analysis. Fourthly, the primary aim of RAPID was not to compare intervention effectiveness across subgroups. Therefore, while the lack of a statistically significant difference in mean weight changes between White and African American subgroups is encouraging, additional research is needed to understand how best to maximize the identification, uptake, and weight loss effectiveness of interventions targeting low-income and minority adults.

10. Conclusion: Scaling Diabetes Prevention Efforts

The RAPID study makes a valuable contribution to the existing research by demonstrating that a community-based adaptation of the DPP lifestyle intervention can lead to meaningful lifestyle changes among predominantly low-income White and African American participants at high risk for type 2 diabetes. These findings enhance our understanding that community delivery of the DPP intervention in a lower-cost format by the YMCA can achieve meaningful weight loss among broader segments of the US population. This has significant implications for ongoing diabetes prevention initiatives involving the YMCA of the USA, UnitedHealth Group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Diabetes Education Program, the National Diabetes Prevention Program, and other partners. These organizations are aligned to demonstrate and evaluate whether community-based models for delivery of the DPP can be effective and sustainable on a national scale.

11. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)?

The DPP is a program designed to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes through lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise.

2. What is the YMCA’s role in diabetes prevention?

The YMCA offers a community-based adaptation of the DPP, providing support and resources to help individuals at risk for diabetes make healthier lifestyle choices.

3. Who is at risk for type 2 diabetes?

Individuals who are overweight or obese, have a family history of diabetes, or have elevated blood glucose levels are at higher risk for developing type 2 diabetes.

4. How effective is the YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program (YDPP)?

The RAPID study showed that participants in the YDPP achieved a 2.3-kilogram greater weight loss at 12 months compared to those receiving standard care.

5. What are the key components of the YDPP intervention?

The YDPP intervention includes goal setting, self-monitoring, moderate physical activity (150 minutes/week), and reduced dietary fat and calorie consumption.

6. How was the RAPID study conducted?

The RAPID study was a randomized comparative effectiveness trial that compared the YDPP to standard clinical care in a diverse population at high risk for type 2 diabetes.

7. What were the limitations of the RAPID study?

Limitations included the short duration of the study (12 months), potential residual selection bias, and the use of point-of-care testing equipment for A1c and lipid outcomes.

8. What were the main findings of the RAPID study?

The RAPID study found that the YDPP led to meaningful weight loss and improved health outcomes among participants at risk for type 2 diabetes.

9. How can community-based interventions help prevent diabetes?

Community-based interventions, like the YDPP, provide accessible and affordable resources that can help individuals make lifestyle changes to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes.

10. What should I do if I think I am at risk for type 2 diabetes?

Consult with your healthcare provider to assess your risk and discuss appropriate prevention strategies, such as lifestyle changes and participation in programs like the DPP or YDPP.

12. Take the Next Step with COMPARE.EDU.VN

Ready to take control of your health? The RAPID study highlights the effectiveness of community-based programs like the YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program in achieving meaningful weight loss and reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes. But with so many options available, how do you choose the right one for you?

At COMPARE.EDU.VN, we provide detailed and objective comparisons of various health and wellness programs to help you make informed decisions. Whether you’re looking for a diabetes prevention program, a weight loss plan, or strategies for improving your overall health, our comprehensive comparisons can guide you.

Visit COMPARE.EDU.VN today to explore your options and find the perfect program to support your health goals. Knowledge is power, and we’re here to empower you to make the best choices for your well-being.

Contact us:

Address: 333 Comparison Plaza, Choice City, CA 90210, United States

Whatsapp: +1 (626) 555-9090

Website: compare.edu.vn