Baseball, a sport steeped in tradition and increasingly driven by data, offers fans endless avenues for player comparison. From batting averages to home runs, traditional stats have long fueled debates. However, modern baseball analysis has introduced more comprehensive metrics like Wins Above Replacement (WAR). Among the various sources for WAR, Baseball-Reference stands out as a widely respected platform. Understanding Baseball-Reference’s WAR (bWAR) is crucial for anyone looking to compare baseball players effectively and delve deeper into player valuation.

Alt text: A sunny day at a baseball stadium, showcasing the vibrant green field and anticipation for player performance comparisons.

WAR attempts to quantify a player’s total contribution to their team in terms of wins. It answers a fundamental question: how many more wins does a player contribute compared to a readily available “replacement-level” player – someone obtainable for the league minimum salary? For instance, a player with a 5.0 bWAR on Baseball-Reference is considered to have added five wins to their team’s record over the season compared to a replacement-level player. This metric allows for player comparisons across different positions and even across different eras, making it a powerful tool for evaluating player value using Baseball-Reference.

Baseball-Reference WAR has gained significant traction in baseball analysis and media. It’s often referenced in discussions about player awards like MVP and Cy Young, providing a quick yet insightful snapshot of a player’s overall worth. While not the sole determinant, a look at recent award seasons reveals that top contenders consistently rank high in both Fangraphs’ fWAR and Baseball-Reference’s bWAR. To effectively compare players, understanding the nuances of how Baseball-Reference calculates bWAR is key.

Delving into Baseball-Reference WAR (bWAR)

While various WAR calculations exist, Baseball-Reference’s bWAR and Fangraphs’ fWAR are the most prominent. These are calculated by leading sabermetric websites with extensive baseball databases. Both platforms calculate WAR separately for position players and pitchers, although their methodologies differ slightly. Despite these differences, bWAR and fWAR are comparable enough to provide a robust picture of player performance when you compare players using baseball reference or Fangraphs.

Both Baseball-Reference and Fangraphs start with the premise of allocating a fixed amount of WAR across all players in a season. For a standard 162-game season, Baseball-Reference distributes approximately 590 WAR to position players and 410 WAR to pitchers. Fangraphs’ allocation is slightly different, suggesting a minor variation in their assessment of pitcher versus position player impact. These subtle allocation differences, along with variations in calculation methods, contribute to potential discrepancies between bWAR and fWAR for individual players. Understanding these nuances is vital when you compare players and their WAR values across different platforms.

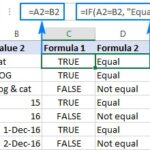

To illustrate the similarities and differences in player valuation, consider the top performers of the 2022 MLB season. Figure 1 compares the top 10 players according to Fangraphs’ fWAR with their corresponding Baseball-Reference bWAR. As you can see, while the rankings are broadly similar, there are individual variations that can impact how you compare players based on these metrics.

Figure 1: Comparison of Top 10 fWAR Players and their Baseball-Reference bWAR in 2022. Data from Fangraphs and Baseball-Reference.

Take Manny Machado as an example. In 2022, Machado was a standout player for the Padres, contributing significantly to their success. His offensive stats were impressive, but when comparing his WAR across platforms, differences emerge. Fangraphs credited him with 7.4 fWAR (2nd among position players), while Baseball-Reference assigned him 6.8 bWAR (7th). This difference, while seemingly small, can shift player rankings when you compare players. The primary reason for such variations often lies in how defensive performance is evaluated, a key differentiator between fWAR and bWAR calculations for position players, which we’ll explore further to aid in your player comparisons.

Calculating bWAR for Position Players on Baseball-Reference

Baseball-Reference’s bWAR for position players is a comprehensive calculation that encompasses various aspects of a player’s game. The formula, while complex, shares a similar structure with Fangraphs’ fWAR, focusing on offensive and defensive contributions.

bWAR Formula (Position Players):

(Batting Runs + Base Running runs +/- Runs from GIDP + Fielding Runs + Positional Adjustment Runs + Replacement Level Runs) / (Runs per win)

The core components are similar to fWAR, but a critical distinction arises in the “Fielding Runs” component. Baseball-Reference utilizes Defensive Runs Saved (DRS) to quantify a player’s defensive contribution, whereas Fangraphs employs Ultimate Zone Rating (UZR). This difference in defensive metrics is often the most significant factor leading to variations between bWAR and fWAR when you compare players.

Both DRS and UZR aim to measure a player’s defensive value in runs above or below average for their position. A zero value represents average defense, positive values indicate above-average defense, and negative values signify below-average defense. However, they differ in their methodologies. DRS, used by Baseball-Reference, typically relies on a single year’s worth of data to assess defensive plays. UZR, used by Fangraphs, incorporates three years of data, potentially providing a more smoothed and long-term view of defensive ability. This difference in data weighting can lead to contrasting defensive evaluations, especially for players with limited track records, impacting player comparisons.

Consider the largest discrepancies between fWAR and bWAR for position players in the 2022 season, as shown in Figure 2. Taylor Walls exhibits a significant difference. As a relatively new player in 2022, the limited data available for UZR might have undervalued his defensive contributions compared to DRS, resulting in a notable difference in WAR when you compare players.

Figure 2: Largest Differences between fWAR and bWAR for Position Players in 2022. Data from Fangraphs and Baseball-Reference.

Brendan Rodgers, a Gold Glove-caliber shortstop for the Colorado Rockies, provides another compelling example. Despite a solid offensive wOBA of .321 in 2022, his fWAR (1.7) and bWAR (4.3) differ significantly. This substantial gap highlights the impact of defensive metric variations when you compare players. Baseball-Reference’s DRS views Rodgers’ defense more favorably than Fangraphs’ UZR, leading to a higher bWAR and a different overall player valuation. This demonstrates how the choice of WAR metric can influence conclusions when you compare players’ total value.

Similarly, catchers like Salvador Perez and Elias Diaz show notable differences between fWAR and bWAR. Defensive evaluation for catchers is particularly complex, encompassing factors like stolen base prevention, blocking pitches, and pitch framing – the skill of subtly influencing strike calls. Pitch framing, a relatively recent area of statistical analysis, can significantly impact a catcher’s defensive value. The discrepancies in bWAR and fWAR for Perez and Diaz can be partly attributed to differences in how these sites account for pitch framing and the weighting of short-term versus long-term defensive data when you compare players.

Amed Rosario’s case further underscores the UZR vs. DRS difference. Like Rodgers, Rosario’s bWAR is considerably higher than his fWAR, again pointing to DRS’s more favorable assessment of his defensive play compared to UZR. In essence, for position players, unless UZR and DRS diverge significantly in their defensive evaluations, bWAR and fWAR tend to be relatively close. However, when defensive metrics differ sharply, it directly impacts WAR and subsequently, how you compare players using these metrics.

Calculating bWAR for Pitchers on Baseball-Reference

When it comes to pitchers, Baseball-Reference and Fangraphs diverge more significantly in their WAR calculations. Instead of directly adapting the position player formula, both sites employ different foundational statistics to estimate a pitcher’s contribution to wins. Baseball-Reference’s bWAR for pitchers relies on Runs Allowed per 9 innings (RA9), while Fangraphs’ fWAR utilizes Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP). Understanding this fundamental difference is crucial when you compare pitchers using either Baseball-Reference or Fangraphs.

Runs Allowed per 9 innings (RA9) is a straightforward metric that simply measures the number of runs a pitcher allows per nine innings pitched, regardless of whether they are earned or unearned.

RA9 Formula:

Runs Allowed per 9 innings (RA9) = (Runs Allowed / Innings Pitched) * 9

RA9 considers all runs, including those potentially influenced by team defense. In contrast, FIP aims to isolate a pitcher’s performance from defensive factors by focusing on outcomes primarily controlled by the pitcher: home runs, walks, hit-by-pitches, and strikeouts.

FIP Formula:

FIP = (13 Home Runs + 3 (Walks + Hit-by-Pitches) – 2 * Strikeouts) / Innings Pitched + FIP Constant

The “FIP Constant” is adjusted annually to ensure league-average FIP aligns with league-average ERA, centering the metric around a familiar scale.

The contrasting philosophies of RA9 and FIP lead to different pitcher valuations in bWAR and fWAR. Baseball-Reference’s bWAR, based on RA9, incorporates the impact of defense on a pitcher’s run prevention. Fangraphs’ fWAR, using FIP, focuses solely on aspects largely within a pitcher’s control, aiming to evaluate pitching performance independent of defense when you compare pitchers.

Consider this illustration, adapted from Baseball-Reference, to highlight the divergence:

Scenario:

- Pitcher A: Throws a perfect game with 20 strikeouts.

- Pitcher B: Throws a perfect game with 0 strikeouts (relying on batted ball outs and defense).

Calculated Metrics:

- Pitcher A: FIP ≈ -1.40, RA ≈ 0.00

- Pitcher B: FIP ≈ 3.20, RA ≈ 0.00

Both pitchers achieved the same outcome (a perfect game, zero runs allowed), but their FIP values differ drastically. FIP penalizes Pitcher B for not accumulating strikeouts and relying on batted balls, even in a perfect game scenario. RA, and consequently bWAR, treats both performances equally in terms of run prevention.

This example, though extreme, highlights the fundamental difference: fWAR tends to favor strikeout pitchers who control the game through strikeouts and limit walks and home runs, while bWAR values run prevention regardless of how it’s achieved. When you compare pitchers, this distinction is critical.

Figure 3 shows the largest discrepancies between fWAR and bWAR for pitchers in 2022. Notably, pitchers dominate the list of largest WAR differences, further emphasizing the impact of the RA9 vs. FIP methodologies.

Figure 3: Largest Differences between fWAR and bWAR for Pitchers in 2022. Data from Fangraphs and Baseball-Reference.

Sandy Alcantara, the 2022 NL Cy Young Award winner, exemplifies this difference. While dominant, Alcantara’s fWAR (5.7) is significantly lower than his bWAR (8.0). Alcantara pitched nearly 230 innings in 2022 but had a relatively modest strikeout rate (8.1 K/9). He excelled at inducing ground balls and double plays, minimizing pitch counts and pitching deep into games. This style is valued more highly by bWAR, which rewards run prevention (RA9) directly, than by fWAR, which prioritizes strikeout-driven dominance (FIP) when you compare pitchers.

Conversely, Kevin Gausman had a higher fWAR (5.7) than bWAR (3.0) in 2022. Gausman’s high strikeout rate (10.6 K/9) is favored by FIP and thus fWAR. Despite allowing more runs than Alcantara in fewer innings, Gausman’s strikeout ability elevates his fWAR relative to bWAR. While strikeouts are not the sole determinant, they are a significant factor in explaining the fWAR vs. bWAR divergence for pitchers, impacting how you compare pitchers based on these metrics.

To assess whether these calculation differences even out over a player’s career, consider the career WAR of Hall of Fame pitchers (Figure 4). This provides a long-term perspective when you compare players across their entire careers.

Figure 4: Career fWAR and bWAR for Hall of Fame Players. Data from Fangraphs and Baseball-Reference.

For most Hall of Fame pitchers, career fWAR and bWAR are reasonably close. Greg Maddux shows the largest difference among this group. Maddux, known for his exceptional command and pitch-to-contact style, had a career ERA of 3.16 and a FIP of 3.26. During his prime with the Atlanta Braves, his ERA (2.63) was notably lower than his FIP (2.93), indicating he benefited from excellent defense and batted ball luck. Fangraphs calculates Maddux’s career fWAR at 116.7, while Baseball-Reference’s bWAR is 106.6, a 10.1 WAR difference over his career. While substantial, this difference doesn’t fundamentally alter Maddux’s Hall of Fame status. It reflects the inherent differences in valuing his particular pitching style when you compare pitchers like Maddux across different WAR metrics.

For the position players in Figure 4, the WAR differences are minimal, often attributable to era-specific variations in baseball and the challenges of retroactively applying advanced defensive metrics across different historical periods when you compare players from different eras.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right WAR for Player Comparison on Baseball-Reference

In summary, significant methodological differences exist between Baseball-Reference’s bWAR and Fangraphs’ fWAR, particularly for pitchers and defensive evaluation. There isn’t a single “correct” WAR metric. Choosing between bWAR and fWAR depends on what aspects of player performance you prioritize when you compare players. Baseball-Reference’s bWAR, rooted in Runs Allowed and Defensive Runs Saved, provides a comprehensive measure of overall run prevention and defensive contribution as captured by Baseball-Reference’s data. Understanding the strengths and limitations of both bWAR and fWAR is essential for any baseball fan seeking to engage with advanced statistics and compare players effectively in today’s data-rich baseball landscape. By using Baseball-Reference and understanding bWAR, you can gain valuable insights when you compare players and deepen your appreciation for the nuances of baseball analysis.