In his insightful book, “The Future of Land Warfare,” Brookings Senior Fellow Michael O’Hanlon challenges a prevailing notion he terms “A major conceptual mistake.” This mistake lies in the belief that large-scale ground operations are relics of the past. O’Hanlon argues against the idea of relegating “messy ground operations to the dustbin of history,” emphasizing the continued relevance of robust land forces. This perspective gains significance when considering the United States Army’s force structure in comparison to other global military powers.

O’Hanlon’s analysis stems from observations of U.S. defense policy shifts, particularly the 2012 and 2014 defense strategic guidance documents. These plans indicated a move away from sizing the U.S. Army primarily for large-scale counterinsurgency and stabilization missions. However, O’Hanlon contends that reducing the Army based on this premise is shortsighted. He advocates for maintaining, and potentially increasing, current force levels to address a spectrum of global security challenges.

His argument extends beyond traditional counterinsurgency and stabilization roles. O’Hanlon highlights the necessity of a strong U.S. Army for deterring conventional threats, specifically mentioning Russian aggression towards NATO allies and North Korean threats against South Korea. Furthermore, he broadens the scope to include “nontraditional scenarios,” such as the alarming possibility of nuclear escalation in conflicts like that between India and Pakistan. This wider perspective underscores the diverse and evolving demands placed on the Us Military Compared To Other Countries who may have more regionally focused defense strategies.

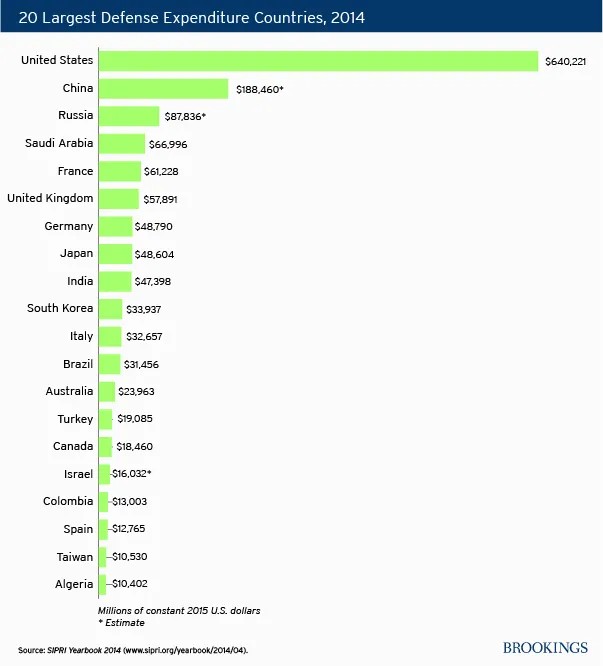

A crucial aspect of understanding the US military compared to other countries lies in examining its budget and troop size. While the United States boasts the largest military budget globally, dwarfing that of any other nation, the size of the U.S. Army in terms of active personnel is not proportionally as dominant. The provided charts visually represent this disparity. One chart illustrates the defense expenditures of the 20 largest spending countries, clearly showing the US at the top. The second chart, however, presents the top 10 active duty armies worldwide, revealing that the U.S. Army, while significant, is not the largest in terms of personnel when compared to nations like China or India.

This comparison highlights a critical point: the US military strategy, while heavily funded, is structured differently from some other major military powers. The US military posture is designed for global power projection, technological superiority, and a wide range of mission types, from high-intensity conflicts to stability operations. This necessitates significant investment in advanced weaponry, logistics, and diverse capabilities, which can be more expensive than maintaining a larger conscript army. Therefore, when the US military is compared to other countries, it’s essential to consider not just troop numbers or budget size in isolation, but also the strategic objectives, technological advantages, and operational doctrines that shape each nation’s defense forces. O’Hanlon’s analysis serves as a timely reminder that a comprehensive assessment of military strength must go beyond simple metrics and account for the complex realities of modern global security.