How Big Is Your Stomach Compared To Your Fist? Your stomach, when empty, is roughly the size of your fist, but it’s incredibly elastic. Visit COMPARE.EDU.VN to explore more about the digestive system. Understanding your stomach’s capacity and function can help you make informed decisions about your eating habits and overall health, leading to a healthier lifestyle.

1. Understanding the Stomach: An Overview

The stomach is a vital organ in the digestive system, acting as a temporary storage and processing unit for the food we consume. It’s a muscular, expandable sac situated between the esophagus and the small intestine. While popular belief might equate stomach size with appetite or body weight, the reality is more nuanced.

1.1. Anatomy of the Stomach

The stomach isn’t just a simple bag; it’s a complex structure with distinct regions:

- Cardia: The point where the esophagus connects to the stomach.

- Fundus: The dome-shaped section located above and to the left of the cardia.

- Body: The main and largest part of the stomach.

- Pylorus: The funnel-shaped region that connects the stomach to the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine.

The pylorus includes the pyloric antrum (connecting to the body) and the pyloric canal, controlled by the pyloric sphincter, which regulates stomach emptying.

1.2. The Empty Stomach: Size Matters

An empty stomach is approximately the size of your fist, around 150ml. This compact size allows it to fit comfortably within the abdominal cavity. The stomach’s remarkable ability to expand is what allows us to consume varying amounts of food and liquid.

1.3. Expansion Capabilities

The stomach can stretch to hold up to 4 liters (or more) of food and fluid—over 75 times its empty volume. This expansion is facilitated by the rugae, large folds in the stomach’s mucosa and submucosa that flatten out as the stomach fills.

1.4. Myth vs. Reality: Stomach Size and Eating Habits

There’s a common misconception that a person’s stomach size correlates with how much they eat or their body weight. However, research indicates that stomach size doesn’t determine body weight. Instead, habitual eating habits influence how much the stomach stretches. Consistently eating large meals can increase the stomach’s capacity over time, while smaller, more frequent meals can maintain or even reduce its size.

2. The Stomach’s Role in Digestion

The stomach plays a crucial role in digestion, both mechanically and chemically. It’s much more than just a holding tank for food.

2.1. Temporary Holding Chamber

One of the primary functions of the stomach is to act as a temporary storage unit. We can ingest food much faster than the small intestine can digest and absorb it. The stomach holds the food, releasing small amounts into the small intestine at a regulated pace.

2.2. Mixing and Churning

The stomach mixes food with gastric juices, breaking it down into a semi-liquid substance called chyme. This process ensures that the food is thoroughly mixed with digestive enzymes, preparing it for further digestion in the small intestine.

2.3. Chemical Digestion

The stomach is involved in the chemical digestion of carbohydrates, proteins, and triglycerides.

- Carbohydrates: The stomach continues the digestion of carbohydrates initiated in the mouth by salivary amylase, until the food mixes with acidic chyme.

- Proteins: The stomach initiates the digestion of proteins through the action of hydrochloric acid (HCl) and the enzyme pepsin.

- Triglycerides: Lingual lipase, activated by the acidic environment, starts breaking down triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerides.

2.4. Nutrient Absorption

While most nutrient absorption occurs in the small intestine, the stomach does absorb some nonpolar substances like alcohol and aspirin.

3. The Three Phases of Gastric Secretion

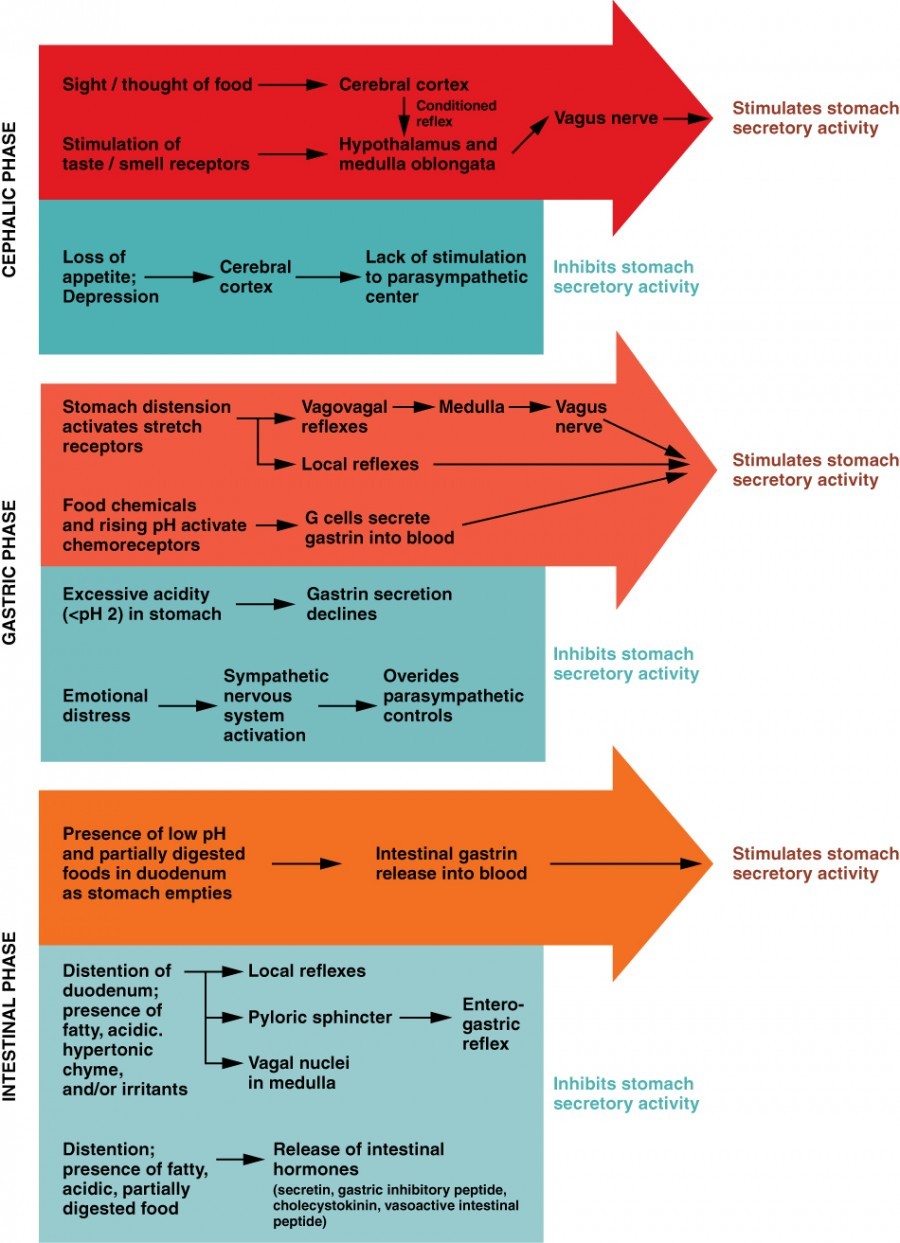

Gastric secretion, the production of gastric juice, is regulated by both nerves and hormones. It occurs in three phases: cephalic, gastric, and intestinal.

3.1. Cephalic Phase

The cephalic phase begins before food even enters the stomach. The smell, taste, sight, or thought of food triggers this phase. Sensory stimuli send impulses to the brain, which then increases gastric secretion to prepare the stomach for digestion. This phase is a conditioned reflex and can be suppressed by factors like depression or loss of appetite.

3.2. Gastric Phase

The gastric phase lasts 3 to 4 hours and is initiated when food enters the stomach. The distention of the stomach activates stretch receptors, which stimulate parasympathetic neurons to release acetylcholine, increasing gastric juice secretion. Partially digested proteins, caffeine, and rising pH levels stimulate the release of gastrin, which further enhances HCl production and smooth muscle contractions.

3.3. Intestinal Phase

The intestinal phase has both excitatory and inhibitory components. When partially digested food fills the duodenum, intestinal mucosal cells release intestinal gastrin, which briefly stimulates gastric juice secretion. However, as the intestine distends with chyme, the enterogastric reflex inhibits secretion and closes the pyloric sphincter to prevent additional chyme from entering the duodenum.

The Three Phases of Gastric Secretion

The Three Phases of Gastric Secretion

4. Protecting the Stomach: The Mucosal Barrier

The stomach’s mucosa is exposed to highly corrosive gastric juice, which includes enzymes capable of digesting proteins—including the stomach itself. To prevent self-digestion, the stomach employs a mucosal barrier.

4.1. Components of the Mucosal Barrier

The mucosal barrier consists of several protective mechanisms:

- Bicarbonate-Rich Mucus: The stomach wall is coated with a thick layer of bicarbonate-rich mucus that neutralizes acid.

- Tight Junctions: Epithelial cells in the stomach’s mucosa are connected by tight junctions that prevent gastric juice from penetrating underlying tissue layers.

- Stem Cells: Stem cells located where gastric glands join gastric pits rapidly replace damaged epithelial cells. The surface epithelium is completely replaced every 3 to 6 days.

4.2. Factors Affecting the Mucosal Barrier

Certain factors can compromise the mucosal barrier, leading to conditions like gastritis or peptic ulcers. These factors include:

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): These drugs can inhibit the production of prostaglandins, which are essential for maintaining the mucosal barrier.

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) Infection: This bacterium can damage the mucosal lining, leading to inflammation and ulceration.

- Excessive Alcohol Consumption: Alcohol can irritate the stomach lining and impair the protective mechanisms of the mucosal barrier.

- Stress: Chronic stress can disrupt the balance of gastric secretions and weaken the mucosal barrier.

5. Mechanical Digestion in Detail

Mechanical digestion in the stomach involves the physical breakdown of food into smaller particles, increasing its surface area for chemical digestion.

5.1. Mixing Waves

Mixing waves, a unique type of peristalsis, occur approximately every 20 seconds after food enters the stomach. These waves mix and soften the food with gastric juices to create chyme. The waves start gently but increase in intensity as they move toward the pylorus.

5.2. Gastric Emptying

Gastric emptying is the process by which chyme is released from the stomach into the duodenum. The pylorus acts as a filter, allowing only liquids and small food particles to pass through the pyloric sphincter. Rhythmic mixing waves force about 3 mL of chyme at a time into the duodenum.

5.3. Regulation of Gastric Emptying

Gastric emptying is regulated by both the stomach and the duodenum. The presence of chyme in the duodenum activates receptors that inhibit gastric secretion, preventing the release of additional chyme until the small intestine is ready to process it.

6. Chemical Digestion: Enzymes and Acids

Chemical digestion involves breaking down food molecules into smaller components through enzymatic and acidic processes.

6.1. Hydrochloric Acid (HCl)

HCl is produced by parietal cells in the stomach and plays several crucial roles:

- Denaturation of Proteins: HCl denatures proteins, unfolding their structure and making them more accessible to enzymatic digestion.

- Activation of Pepsinogen: HCl converts pepsinogen, an inactive precursor, into pepsin, the active enzyme that breaks down proteins.

- Killing Bacteria: HCl helps kill bacteria ingested with food, reducing the risk of infection.

6.2. Pepsin

Pepsin is the primary enzyme responsible for protein digestion in the stomach. It breaks down proteins into smaller peptides, which are further digested in the small intestine.

6.3. Lingual Lipase

Lingual lipase, secreted by the salivary glands, is activated by the acidic environment of the stomach. It breaks down triglycerides into fatty acids and glycerides.

6.4. Rennin

In infants, gastric glands produce rennin, an enzyme that helps digest milk protein.

7. The Importance of Intrinsic Factor

Intrinsic factor is a glycoprotein produced by parietal cells in the stomach. It is essential for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine.

7.1. Vitamin B12 Absorption

Vitamin B12 is necessary for the production of mature red blood cells and normal neurological functioning. Without intrinsic factor, vitamin B12 cannot be properly absorbed, leading to vitamin B12 deficiency and potential health problems.

7.2. Consequences of Intrinsic Factor Deficiency

Deficiency in intrinsic factor can result from conditions like:

- Pernicious Anemia: An autoimmune condition in which the body attacks parietal cells, reducing intrinsic factor production.

- Gastrectomy: Surgical removal of the stomach, which eliminates the source of intrinsic factor.

- Atrophic Gastritis: Chronic inflammation of the stomach lining, leading to reduced parietal cell function.

Individuals with intrinsic factor deficiency often require vitamin B12 injections to maintain adequate levels.

8. Factors Affecting Stomach Emptying Rate

The rate at which the stomach empties its contents into the duodenum can be influenced by several factors.

8.1. Composition of Food

The type of food consumed affects stomach emptying rate:

- Carbohydrates: Foods high in carbohydrates empty the fastest.

- Proteins: High-protein foods empty more slowly than carbohydrates.

- Fats: Foods high in fats (triglycerides) remain in the stomach the longest.

8.2. Hormonal and Neural Regulation

Hormones like cholecystokinin (CCK) and secretin, released by the small intestine, can slow gastric emptying. The enterogastric reflex, triggered by the presence of chyme in the duodenum, also inhibits gastric emptying.

8.3. Physical Factors

The volume and consistency of food can also affect emptying rate. Larger volumes and solid foods tend to empty more slowly than smaller volumes and liquids.

9. Common Stomach Problems and Solutions

Understanding common stomach issues can help individuals take proactive steps to maintain their digestive health.

9.1. Acid Reflux and GERD

Acid reflux occurs when stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, causing heartburn and discomfort. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic form of acid reflux.

Solutions:

- Dietary Changes: Avoid trigger foods like caffeine, alcohol, spicy foods, and fatty foods.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Maintain a healthy weight, avoid eating large meals, and don’t lie down immediately after eating.

- Medications: Over-the-counter antacids, H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can help reduce stomach acid production.

9.2. Gastritis

Gastritis is the inflammation of the stomach lining. It can be caused by H. pylori infection, NSAIDs, excessive alcohol consumption, or autoimmune disorders.

Solutions:

- Antibiotics: If gastritis is caused by H. pylori, antibiotics are prescribed to eradicate the infection.

- Acid-Reducing Medications: H2 blockers and PPIs can reduce stomach acid and promote healing.

- Dietary Changes: Avoid irritants like alcohol, caffeine, and spicy foods.

9.3. Peptic Ulcers

Peptic ulcers are sores that develop in the lining of the stomach, esophagus, or small intestine. They are often caused by H. pylori infection or NSAID use.

Solutions:

- Antibiotics: If H. pylori is present, antibiotics are used to eliminate the infection.

- Acid-Reducing Medications: PPIs are commonly prescribed to reduce stomach acid and allow the ulcer to heal.

- Lifestyle Changes: Avoid smoking, alcohol, and NSAIDs.

9.4. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

IBS is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder that affects the large intestine. While the stomach is not directly affected, IBS symptoms can include abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits.

Solutions:

- Dietary Management: Identify and avoid trigger foods.

- Stress Management: Practice relaxation techniques like meditation and yoga.

- Medications: Antispasmodics, antidiarrheals, and antidepressants may be prescribed to manage symptoms.

10. Maintaining a Healthy Stomach

Adopting healthy habits can support optimal stomach function and prevent digestive issues.

10.1. Balanced Diet

Eating a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins provides essential nutrients and fiber for digestive health.

10.2. Regular Meal Times

Eating regular meals at consistent times can help regulate gastric secretions and promote efficient digestion.

10.3. Portion Control

Practicing portion control can prevent overeating and reduce the strain on the stomach.

10.4. Hydration

Drinking plenty of water helps maintain proper hydration, which is essential for digestive processes.

10.5. Probiotics

Consuming probiotics through foods like yogurt or supplements can support a healthy gut microbiome, which is beneficial for digestion.

10.6. Stress Management

Managing stress through relaxation techniques, exercise, and adequate sleep can reduce the impact of stress on the digestive system.

11. The Gut-Brain Connection

The gut-brain connection refers to the bidirectional communication between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain. This connection plays a significant role in regulating digestion, mood, and overall health.

11.1. Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve is a major component of the gut-brain axis, transmitting signals between the brain and the digestive system.

11.2. Neurotransmitters

The gut produces neurotransmitters like serotonin, which influence mood and behavior. A healthy gut microbiome can positively impact mental well-being.

11.3. Impact of Stress

Stress can disrupt the gut-brain connection, leading to digestive issues like IBS and acid reflux.

12. The Future of Stomach Research

Ongoing research continues to uncover new insights into the stomach’s function and its role in overall health.

12.1. Microbiome Studies

Studies on the gut microbiome are revealing the complex interactions between gut bacteria and digestive processes.

12.2. Personalized Nutrition

Personalized nutrition approaches aim to tailor dietary recommendations based on individual gut microbiome profiles and genetic factors.

12.3. Advanced Diagnostic Techniques

Advanced diagnostic techniques, such as high-resolution endoscopy and molecular analysis, are improving the detection and management of stomach disorders.

13. Comparing Stomach Capacity: Factors and Variations

Understanding how stomach capacity varies among individuals and the factors that influence it can provide valuable insights into digestive health and eating habits.

13.1. Individual Differences

Stomach capacity can vary significantly among individuals due to genetic factors, eating habits, and lifestyle. Some people naturally have larger or more elastic stomachs than others.

13.2. Impact of Eating Habits

Habitual eating patterns play a crucial role in determining stomach capacity. Regularly consuming large meals can stretch the stomach over time, increasing its capacity. Conversely, eating smaller, more frequent meals can help maintain or reduce stomach size.

13.3. Age-Related Changes

As people age, the stomach’s elasticity may decrease, leading to a reduced capacity. Older adults might experience a feeling of fullness more quickly and may need to eat smaller meals.

13.4. Medical Conditions and Surgeries

Certain medical conditions and surgeries can significantly impact stomach capacity. Gastric bypass surgery, for example, reduces the size of the stomach to promote weight loss. Conditions like gastroparesis (delayed stomach emptying) can also affect how the stomach handles food.

13.5. The Role of Genetics

Genetics can influence the baseline size and elasticity of the stomach. While specific genes responsible for stomach capacity are not yet fully identified, genetic predisposition likely plays a role.

13.6. Stomach Capacity and Weight Management

While stomach size doesn’t directly determine body weight, it can influence eating behavior and satiety. People with larger stomach capacities may need to consume more food to feel full, potentially contributing to overeating and weight gain.

13.7. Techniques to Manage Stomach Capacity

- Mindful Eating: Paying attention to hunger and fullness cues can help prevent overeating and manage stomach capacity.

- Portion Control: Using smaller plates and measuring portions can help regulate food intake.

- Frequent, Small Meals: Eating smaller meals more frequently can help prevent the stomach from stretching excessively.

- High-Fiber Foods: Including fiber-rich foods in the diet can promote satiety and reduce overall food consumption.

14. The Psychology of Eating and Stomach Size

The relationship between the psychology of eating and stomach size is complex. Emotional, social, and environmental factors can influence eating behavior and, consequently, impact stomach capacity over time.

14.1. Emotional Eating

Emotional eating involves consuming food in response to emotions, such as stress, sadness, or boredom. This behavior can lead to overeating and stretching of the stomach.

14.2. Social Influences

Social situations, such as gatherings and celebrations, often involve large amounts of food. Social pressure to eat can lead to exceeding normal stomach capacity.

14.3. Environmental Cues

Environmental cues, such as the availability of palatable foods and the size of serving containers, can influence food consumption. Larger containers and readily available snacks can promote overeating.

14.4. Mindful Eating Practices

Mindful eating involves paying attention to the sensory experience of eating, including the taste, texture, and aroma of food. This practice can help individuals become more aware of their hunger and fullness cues, preventing overeating.

14.5. Cognitive Restraint

Cognitive restraint refers to the conscious effort to restrict food intake. While it can be effective in the short term, it can also lead to rebound eating and bingeing, potentially stretching the stomach.

14.6. Impact on Stomach Capacity

Consistent emotional eating, social overeating, and environmental cues can lead to chronic overeating, increasing stomach capacity over time. Mindful eating and cognitive strategies can help manage eating behavior and prevent excessive stretching of the stomach.

15. Advanced Techniques for Stomach Analysis

Modern medical technology provides several advanced techniques for analyzing the stomach’s structure and function. These techniques are valuable for diagnosing and managing various stomach disorders.

15.1. Endoscopy

Endoscopy involves inserting a thin, flexible tube with a camera attached into the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. This allows physicians to visualize the lining of these organs, detect abnormalities, and take biopsies for further analysis.

15.2. Manometry

Manometry measures the pressure and contractions within the stomach and esophagus. It is used to assess motility disorders, such as gastroparesis and achalasia.

15.3. Gastric Emptying Studies

Gastric emptying studies assess the rate at which food empties from the stomach into the small intestine. These studies are used to diagnose gastroparesis and other emptying disorders.

15.4. Imaging Techniques

Imaging techniques, such as CT scans and MRI, can provide detailed images of the stomach’s structure and detect abnormalities, such as tumors or obstructions.

15.5. Capsule Endoscopy

Capsule endoscopy involves swallowing a small, wireless camera that captures images of the digestive tract as it passes through. This technique is useful for visualizing areas that are difficult to reach with traditional endoscopy.

15.6. Biomarker Analysis

Biomarker analysis involves measuring specific substances in the blood or stomach fluid to assess stomach function and detect disease. For example, pepsinogen levels can be used to assess the health of the stomach lining.

16. Dietary Strategies to Optimize Stomach Health

Adopting specific dietary strategies can significantly improve stomach health, prevent digestive issues, and enhance overall well-being.

16.1. High-Fiber Diet

A diet rich in fiber promotes healthy digestion by adding bulk to the stool, preventing constipation, and supporting a healthy gut microbiome. Good sources of fiber include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes.

16.2. Probiotic-Rich Foods

Consuming probiotic-rich foods, such as yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi, can help maintain a balanced gut microbiome and improve digestion.

16.3. Anti-Inflammatory Foods

Including anti-inflammatory foods in the diet can reduce inflammation in the stomach and digestive tract. Examples include fatty fish, olive oil, nuts, seeds, and colorful fruits and vegetables.

16.4. Avoid Trigger Foods

Identifying and avoiding trigger foods that cause digestive symptoms can significantly improve stomach health. Common trigger foods include caffeine, alcohol, spicy foods, fatty foods, and processed foods.

16.5. Small, Frequent Meals

Eating smaller, more frequent meals can prevent overeating and reduce the strain on the stomach. This approach can also help regulate gastric secretions and maintain stable blood sugar levels.

16.6. Hydration

Drinking plenty of water throughout the day is essential for maintaining proper hydration and supporting digestive processes.

16.7. Mindful Eating

Practicing mindful eating can help individuals become more aware of their hunger and fullness cues, preventing overeating and promoting healthy digestion.

17. Exercise and Its Impact on Gastric Function

Regular exercise can positively impact gastric function by improving digestion, reducing stress, and promoting a healthy gut microbiome.

17.1. Improved Digestion

Exercise can stimulate digestive motility, helping to move food through the digestive tract more efficiently. This can prevent constipation and bloating.

17.2. Stress Reduction

Exercise is a powerful stress reliever. Reducing stress levels can improve gastric function by preventing stress-related digestive symptoms, such as acid reflux and IBS.

17.3. Enhanced Gut Microbiome

Studies have shown that regular exercise can enhance the diversity and composition of the gut microbiome, promoting a healthier digestive system.

17.4. Types of Exercise

Both aerobic exercise and strength training can benefit gastric function. Aerobic activities, such as walking, running, and swimming, can stimulate digestive motility, while strength training can improve overall metabolic health.

17.5. Timing of Exercise

The timing of exercise can also impact gastric function. Exercising after a large meal can delay gastric emptying, while exercising on an empty stomach can lead to discomfort. Finding the right balance is key.

18. Innovative Treatments for Stomach Disorders

Advancements in medical technology and research have led to innovative treatments for various stomach disorders, offering new hope for patients.

18.1. Minimally Invasive Surgery

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, such as laparoscopic and robotic surgery, allow surgeons to perform complex procedures with smaller incisions, resulting in less pain, faster recovery, and reduced risk of complications.

18.2. Endoscopic Therapies

Endoscopic therapies involve using specialized instruments passed through an endoscope to treat stomach disorders. Examples include endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for removing precancerous lesions and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for treating early-stage stomach cancer.

18.3. Bioelectronic Medicine

Bioelectronic medicine involves using electrical stimulation to modulate nerve activity and treat stomach disorders. For example, vagal nerve stimulation has shown promise in treating gastroparesis and other motility disorders.

18.4. Targeted Drug Delivery

Targeted drug delivery systems aim to deliver medications directly to the site of disease in the stomach, reducing systemic side effects and improving treatment efficacy.

18.5. Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy involves using the body’s own immune system to fight stomach cancer. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, for example, have shown significant success in treating advanced stomach cancer.

19. Debunking Myths About Stomach Size and Function

Many myths and misconceptions surround stomach size and function. Understanding the facts can help individuals make informed decisions about their health.

19.1. Myth: Stomach Size Determines Appetite

Fact: While stomach capacity can influence how much food is needed to feel full, appetite is primarily regulated by hormones and neurological signals in the brain.

19.2. Myth: Stretching Your Stomach Leads to Permanent Increase in Size

Fact: The stomach is highly elastic and can return to its normal size after stretching. However, chronic overeating can lead to long-term increases in stomach capacity.

19.3. Myth: Eating Small, Frequent Meals Shrinks Your Stomach

Fact: Eating small, frequent meals can help prevent the stomach from stretching excessively, but it doesn’t necessarily shrink the stomach. The stomach’s elasticity allows it to adjust to different eating patterns.

19.4. Myth: Stomach Acid is Always Harmful

Fact: Stomach acid is essential for digesting proteins and killing bacteria. However, excessive stomach acid can lead to acid reflux and other digestive issues.

19.5. Myth: All Stomach Pain is Due to Ulcers

Fact: Stomach pain can be caused by various factors, including gastritis, acid reflux, IBS, and muscle strain. Ulcers are just one potential cause.

19.6. Myth: You Can “Cleanse” Your Stomach with Special Diets

Fact: The stomach is self-cleaning and doesn’t require special diets or cleanses. A balanced diet and healthy lifestyle are sufficient for maintaining stomach health.

20. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Stomach Size and Function

Here are some frequently asked questions about stomach size and function:

-

Is stomach size related to how much I eat?

Yes, habitual eating patterns can influence stomach size. Consistently eating large meals can stretch the stomach over time, increasing its capacity.

-

Can I shrink my stomach by eating less?

Eating smaller, more frequent meals can help prevent the stomach from stretching excessively and may help it return to its normal size.

-

What is the normal size of an empty stomach?

An empty stomach is approximately the size of your fist, around 150ml.

-

How much can the stomach stretch?

The stomach can stretch to hold up to 4 liters (or more) of food and fluid—over 75 times its empty volume.

-

What factors affect stomach emptying rate?

The composition of food (carbohydrates, proteins, fats), hormonal and neural regulation, and physical factors (volume and consistency of food) can affect stomach emptying rate.

-

What is the mucosal barrier and why is it important?

The mucosal barrier protects the stomach from self-digestion by gastric juice. It consists of bicarbonate-rich mucus, tight junctions between epithelial cells, and stem cells that rapidly replace damaged cells.

-

What is intrinsic factor and why do I need it?

Intrinsic factor is a glycoprotein produced by parietal cells in the stomach that is essential for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine.

-

What are common stomach problems and how can I prevent them?

Common stomach problems include acid reflux, gastritis, and peptic ulcers. They can be prevented by maintaining a balanced diet, avoiding trigger foods, practicing stress management, and getting regular exercise.

-

How does exercise affect stomach function?

Regular exercise can improve digestion, reduce stress, and promote a healthy gut microbiome, all of which positively impact gastric function.

-

What are some innovative treatments for stomach disorders?

Innovative treatments include minimally invasive surgery, endoscopic therapies, bioelectronic medicine, targeted drug delivery, and immunotherapy.

Understanding the complexities of your stomach, its capacity, and its functions is a key step toward making informed decisions about your diet and lifestyle. For more detailed comparisons and information on digestive health, visit COMPARE.EDU.VN.

Are you struggling to compare different digestive health options? Visit COMPARE.EDU.VN for comprehensive and objective comparisons to help you make the best choice. Our team at 333 Comparison Plaza, Choice City, CA 90210, United States, is dedicated to providing you with the information you need. Contact us via WhatsApp at +1 (626) 555-9090 or visit our website. Let compare.edu.vn be your guide to better digestive health and informed decisions.