Are Comparative Research Studies Less Valid Than Experiments? Yes, while comparative research provides valuable insights, it generally holds less internal validity than experiments due to the lack of random assignment. This means comparative studies are more susceptible to confounding variables, making it harder to establish definitive cause-and-effect relationships, but COMPARE.EDU.VN helps you understand these nuances. To make well-informed decisions, considering the context, research design, and potential biases is critical; with the help of comprehensive analysis and methodical approach on COMPARE.EDU.VN, you will also be able to assess different methodologies, evaluate research methodologies and minimise confirmation bias.

1. Understanding Research Validity: A Comparative Overview

When evaluating research, validity is paramount. It essentially asks: Does the research truly measure what it intends to measure? In the context of comparing different research approaches, it is crucial to differentiate between internal and external validity.

1.1 Internal vs. External Validity

Internal validity refers to the degree to which a study can confidently establish a cause-and-effect relationship. High internal validity implies that the observed effects on the dependent variable are indeed caused by the independent variable and not by confounding factors.

External validity, on the other hand, concerns the generalizability of the study findings to other populations, settings, or times. A study with high external validity can be confidently applied to real-world scenarios beyond the specific study context.

1.2 The Gold Standard: Experimental Research

Experimental research is often considered the gold standard for establishing causality. Here’s why:

- Manipulation of Variables: Researchers actively manipulate the independent variable (the presumed cause).

- Random Assignment: Participants are randomly assigned to different conditions (e.g., treatment group vs. control group).

Random assignment is the cornerstone of experimental research. It ensures that any pre-existing differences between participants are evenly distributed across groups, minimizing the influence of confounding variables. This allows researchers to isolate the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

1.3 The Nature of Comparative Research

Comparative research involves examining and contrasting different groups, phenomena, or interventions. Unlike experimental research, comparative studies typically lack random assignment. This absence of random assignment is the primary reason why comparative research often has lower internal validity than experiments.

2. The Crux of the Matter: Random Assignment and Confounding Variables

The absence of random assignment in comparative research introduces the risk of confounding variables. These are extraneous factors that are related to both the independent and dependent variables, potentially distorting the true relationship between them.

2.1 Understanding Confounding Variables

Consider a study comparing the academic performance of students in two different schools. One school implements a new teaching method (the independent variable), while the other continues with the traditional approach. If students are not randomly assigned to these schools, pre-existing differences between the student populations (e.g., socioeconomic status, parental involvement) could influence academic performance (the dependent variable). These differences would be confounding variables, making it difficult to determine whether the new teaching method truly caused any observed differences in performance.

2.2 Threats to Internal Validity in Comparative Research

Several specific threats to internal validity are common in comparative research:

- Selection Bias: When participants are not randomly assigned, the groups being compared may differ systematically in ways that affect the outcome.

- History: Events occurring outside the study may affect one group but not the other, leading to spurious differences.

- Maturation: Natural changes occurring over time (e.g., developmental changes in children) may affect one group differently.

- Testing: Repeatedly measuring the dependent variable may affect participants’ responses.

- Instrumentation: Changes in the measurement instrument or procedure may introduce bias.

- Regression to the Mean: Extreme scores on an initial measurement tend to move closer to the average on subsequent measurements.

- Attrition: Differential dropout rates between groups can lead to biased results.

2.3 Quasi-Experimental Designs: Bridging the Gap

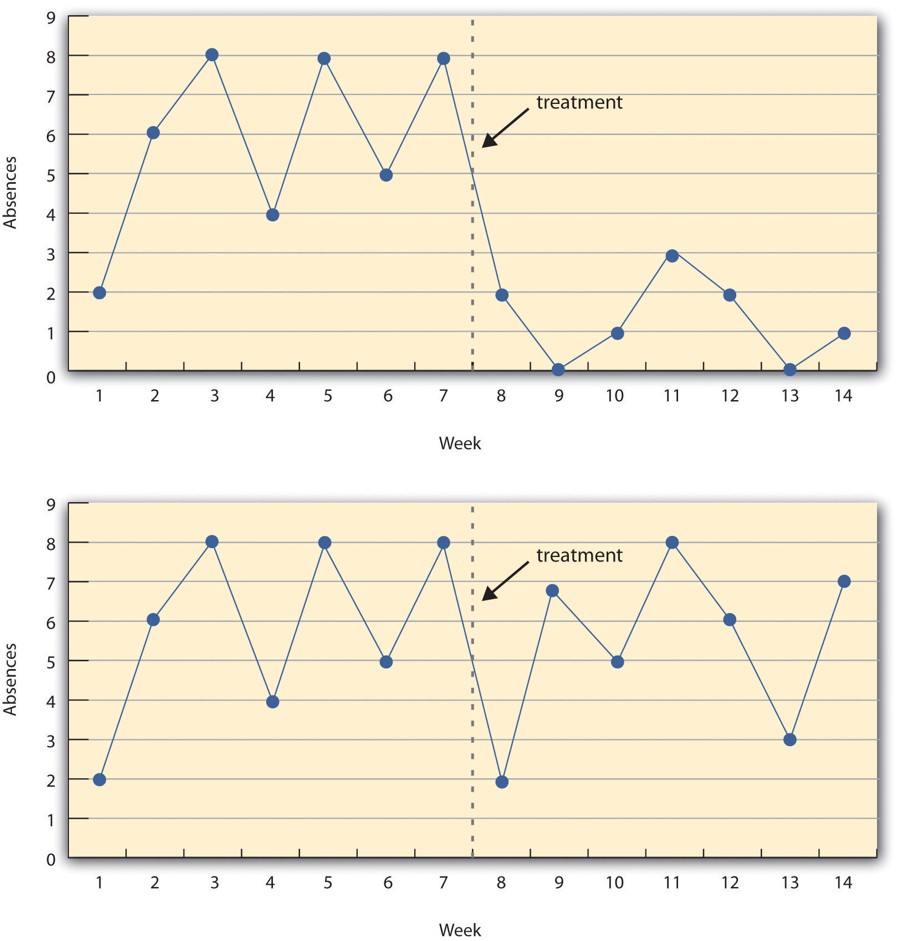

Quasi-experimental designs attempt to mitigate some of the limitations of comparative research. These designs involve manipulating the independent variable but without random assignment. Common types of quasi-experimental designs include:

- Nonequivalent Groups Design: Comparing pre-existing groups that are not randomly assigned.

- Pretest-Posttest Design: Measuring the dependent variable before and after an intervention, without a control group.

- Interrupted Time Series Design: Examining trends in the dependent variable before and after an intervention, using multiple measurements over time.

While quasi-experimental designs offer some control over confounding variables, they still fall short of true experiments in terms of internal validity.

3. Navigating the Landscape: Types of Comparative Research

Comparative research encompasses a broad range of methodologies, each with its own strengths and limitations.

3.1 Cross-Sectional Studies

Cross-sectional studies involve collecting data from different groups at a single point in time. These studies are useful for examining associations between variables but cannot establish causality.

- Example: A survey comparing the health behaviors of smokers and non-smokers.

3.2 Case-Control Studies

Case-control studies compare individuals with a particular condition (cases) to a control group without the condition. These studies are often used to investigate risk factors for diseases.

- Example: A study comparing the past exposures of lung cancer patients to a group of healthy individuals.

3.3 Cohort Studies

Cohort studies follow a group of individuals over time, tracking the development of outcomes of interest. These studies can establish temporal precedence (i.e., that the presumed cause occurred before the effect), which is a crucial step in establishing causality.

- Example: A study following a group of smokers and non-smokers over several decades to compare their rates of lung cancer.

3.4 Comparative Case Studies

Comparative case studies involve in-depth analysis of multiple cases to identify common patterns or differences. This approach is often used in qualitative research.

- Example: A study comparing the implementation of a new policy in several different organizations.

Comparative case studies help find common patterns or differences, enhancing understanding of complex issues.

Comparative case studies help find common patterns or differences, enhancing understanding of complex issues.

4. Elevating Validity: Strategies for Comparative Research

While comparative research may not reach the internal validity levels of experimental research, there are strategies to strengthen its validity and minimize bias.

4.1 Matching

Matching involves selecting participants for the comparison groups who are similar on key variables (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status). This reduces the likelihood that these variables will confound the results.

4.2 Statistical Control

Statistical techniques, such as regression analysis, can be used to control for the effects of confounding variables. This involves statistically adjusting for the influence of these variables on the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

4.3 Propensity Score Matching

Propensity score matching is a statistical technique that estimates the probability of a participant being assigned to a particular group based on their observed characteristics. Participants with similar propensity scores are then matched, creating comparison groups that are more similar than they would be without matching.

4.4 Instrumental Variables

Instrumental variables are variables that are related to the independent variable but not to the confounding variables. These variables can be used to estimate the causal effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

4.5 Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis involves assessing how the results of the study would change if the assumptions about confounding variables were different. This helps to determine the robustness of the findings.

5. The Big Picture: When to Use Comparative Research

Despite its limitations, comparative research remains a valuable tool in many situations.

5.1 Ethical Considerations

In some cases, it may be unethical to conduct an experiment. For example, it would be unethical to randomly assign people to smoking or non-smoking conditions to study the effects of smoking on lung cancer.

5.2 Practical Constraints

Experiments may be impractical in some real-world settings. For example, it may be difficult to randomly assign students to different schools or classrooms.

5.3 Exploratory Research

Comparative research is useful for exploring complex phenomena and generating hypotheses for future research.

5.4 Real-World Relevance

Comparative studies often have higher external validity than experiments because they are conducted in real-world settings.

6. Case Studies: Illustrating Validity in Comparative Research

To further clarify the concepts of validity in comparative research, let’s examine a few case studies.

6.1 Case Study 1: Comparing Educational Interventions

A school district wants to compare the effectiveness of two different reading programs: Program A and Program B. They implement Program A in one school and Program B in another school, then compare the reading scores of students in the two schools.

-

Threats to Validity:

- Selection Bias: The students in the two schools may differ in terms of their prior reading skills, socioeconomic status, or parental involvement.

- History: Events occurring outside the study (e.g., a local news story about the importance of reading) may affect one school but not the other.

- Maturation: Students in one school may be at a different developmental stage than students in the other school.

-

Strategies to Improve Validity:

- Matching: Select schools with similar demographics and prior academic performance.

- Statistical Control: Use regression analysis to control for the effects of confounding variables.

- Propensity Score Matching: Match students based on their propensity to be assigned to each school.

6.2 Case Study 2: Comparing Healthcare Policies

A state government wants to compare the impact of two different healthcare policies on patient outcomes. They implement Policy A in one region of the state and Policy B in another region, then compare the health outcomes of patients in the two regions.

-

Threats to Validity:

- Selection Bias: The patients in the two regions may differ in terms of their health status, access to care, or insurance coverage.

- History: Changes in the healthcare system or economy may affect one region but not the other.

- Instrumentation: Differences in the way health outcomes are measured in the two regions may introduce bias.

-

Strategies to Improve Validity:

- Matching: Select regions with similar demographics and healthcare infrastructure.

- Statistical Control: Use regression analysis to control for the effects of confounding variables.

- Instrumental Variables: Use variables that are related to the healthcare policies but not to the confounding variables.

6.3 Case Study 3: Comparing Business Strategies

A company wants to compare the effectiveness of two different marketing strategies on sales. They implement Strategy A in one region and Strategy B in another region, then compare the sales in the two regions.

-

Threats to Validity:

- Selection Bias: The customers in the two regions may differ in terms of their demographics, preferences, or purchasing power.

- History: Changes in the economy or competitive landscape may affect one region but not the other.

- Instrumentation: Differences in the way sales are measured in the two regions may introduce bias.

-

Strategies to Improve Validity:

- Matching: Select regions with similar demographics and market conditions.

- Statistical Control: Use regression analysis to control for the effects of confounding variables.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Assess how the results of the study would change if the assumptions about confounding variables were different.

7. The Ongoing Debate: Comparative vs. Experimental Research

The debate over the relative validity of comparative and experimental research is ongoing. Some argue that experiments are always superior because of their ability to establish causality. Others argue that comparative research is more relevant to real-world problems and that its limitations can be addressed through careful design and analysis.

7.1 Arguments for Experimental Research

- Causality: Experiments provide the strongest evidence for causality.

- Control: Experiments allow researchers to control for confounding variables.

- Replication: Experiments can be replicated to verify findings.

7.2 Arguments for Comparative Research

- Relevance: Comparative research is often more relevant to real-world problems.

- Feasibility: Experiments may be impractical or unethical in some situations.

- Exploration: Comparative research is useful for exploring complex phenomena.

- External Validity: Comparative studies often have higher external validity than experiments.

7.3 Finding the Right Balance

The best approach often involves combining elements of both comparative and experimental research. For example, researchers may conduct a comparative study to identify potential risk factors for a disease, then conduct an experiment to test the effectiveness of an intervention to reduce those risk factors.

8. The Role of COMPARE.EDU.VN in Navigating Research Validity

Understanding the nuances of research validity can be challenging. COMPARE.EDU.VN serves as a valuable resource for navigating this complex landscape.

8.1 Providing Comprehensive Comparisons

COMPARE.EDU.VN offers comprehensive comparisons of different research methodologies, highlighting their strengths and limitations. This empowers users to critically evaluate research findings and make informed decisions.

8.2 Demystifying Research Terminology

COMPARE.EDU.VN provides clear and concise definitions of key research terms, such as internal validity, external validity, confounding variables, and quasi-experimental designs. This helps users to better understand research reports and articles.

8.3 Promoting Critical Thinking

COMPARE.EDU.VN encourages users to think critically about research findings and to consider the potential for bias. This helps to prevent the acceptance of unsubstantiated claims.

8.4 Connecting Users with Experts

COMPARE.EDU.VN connects users with experts in various fields who can provide guidance on research methodology and interpretation. This ensures that users have access to the best available information.

9. Addressing Common Concerns: FAQ on Research Validity

To further clarify the concepts of research validity, let’s address some frequently asked questions.

Q1: What is the difference between validity and reliability?

A: Validity refers to the accuracy of a measurement (i.e., whether it measures what it is supposed to measure), while reliability refers to the consistency of a measurement (i.e., whether it produces the same results under the same conditions).

Q2: Can a study be reliable but not valid?

A: Yes, a study can be reliable but not valid. For example, a scale that consistently measures weight incorrectly is reliable but not valid.

Q3: Can a study be valid but not reliable?

A: It is difficult for a study to be valid but not reliable. If a measurement is not consistent, it is unlikely to be accurate.

Q4: How can I assess the validity of a research study?

A: To assess the validity of a research study, consider the following:

- The research design

- The sampling method

- The measurement instruments

- The statistical analysis

- The potential for confounding variables

- The authors’ conclusions

Q5: What are some common threats to validity in research?

A: Some common threats to validity in research include:

- Selection bias

- History

- Maturation

- Testing

- Instrumentation

- Regression to the mean

- Attrition

Q6: How can I improve the validity of my own research?

A: To improve the validity of your own research, consider the following:

- Use a strong research design

- Use random sampling

- Use valid and reliable measurement instruments

- Use appropriate statistical analysis

- Control for confounding variables

- Be transparent about the limitations of your study

Q7: Is it always necessary to have a control group in research?

A: While a control group is not always necessary, it is often helpful for establishing causality. A control group allows researchers to compare the outcomes of the treatment group to a group that did not receive the treatment.

Q8: What is the difference between internal and external validity?

A: Internal validity refers to the degree to which a study can confidently establish a cause-and-effect relationship, while external validity concerns the generalizability of the study findings to other populations, settings, or times.

Q9: Can a study have high internal validity but low external validity?

A: Yes, a study can have high internal validity but low external validity. For example, a laboratory experiment may have high internal validity but low external validity because the conditions are artificial.

Q10: How can I balance the need for internal and external validity in my research?

A: Balancing the need for internal and external validity often involves making trade-offs. Researchers may need to sacrifice some external validity in order to achieve higher internal validity, or vice versa. The best approach depends on the specific research question and the context of the study.

10. Making Informed Decisions with COMPARE.EDU.VN

In conclusion, while comparative research may have lower internal validity than experiments, it remains a valuable tool for exploring complex phenomena and generating hypotheses. By understanding the limitations of comparative research and employing strategies to mitigate bias, researchers can strengthen the validity of their findings. At COMPARE.EDU.VN, we provide the resources and expertise you need to navigate the complexities of research validity and make informed decisions.

Want to explore more research methodologies and their validity? Visit COMPARE.EDU.VN today to discover comprehensive comparisons and expert insights. Make smarter, more informed decisions with the help of our detailed analyses.

Contact Us:

Address: 333 Comparison Plaza, Choice City, CA 90210, United States

WhatsApp: +1 (626) 555-9090

Website: compare.edu.vn