Gus Mueller: Welcome back to compare.edu.vn. Today, we delve into a topic that might sound foundational, yet remains a point of discussion and refinement in audiology since the 1930s: speech recognition testing. Dr. Ben Hornsby and I recently found ourselves in a familiar audiologic debate, sparked by observing a gap between best-practice teaching at Vanderbilt and the varied approaches in clinical settings. This led us back to the literature, a necessary step to reaffirm our understanding and address the discrepancies we’ve noted. Ben has spent considerable time in the library, unearthing key insights, and while I come with fewer articles, I bring a wealth of practical experience and opinions. Let’s see where the data and our perspectives align.

The Core Purpose of Word Recognition Testing

Almost every audiologist performs word recognition tests, but the fundamental question remains: Why? What are we truly aiming to uncover about our patients? For me, the objective is clear: to pinpoint a patient’s peak word recognition ability under carefully controlled, standardized conditions. We want to know their optimal performance – the best possible outcome we can expect.

It’s equally crucial to define what this test is not designed to do. It’s not a simulation of real-world hearing. Monosyllabic words presented through headphones in a sound booth, devoid of visual cues and background noise, cannot replicate the complexities of daily listening environments. Furthermore, testing at a fixed level above the Speech Reception Threshold (SRT) is not inherently meaningful. As we proceed, keep in mind our core objective: to establish the patient’s best possible word recognition score in a standardized manner, ensuring findings are reliable and medically recordable.

If we can accurately determine this optimum performance, often termed PB-Max, how can we leverage it clinically? Monosyllabic testing in quiet is a staple in audiology; there must be valid reasons. Indeed, there are at least four key clinical applications:

- Consistency Check: To evaluate if word recognition performance aligns with the pure-tone audiogram, confirming expected patterns for cochlear pathology.

- Asymmetry Detection: To identify unexpected discrepancies between ears that aren’t predicted by pure-tone thresholds, potentially signaling retrocochlear issues.

- Performance Monitoring: To track changes in word recognition over time through serial testing, crucial for monitoring progression or intervention effectiveness.

- Amplification Guidance: To inform decisions about hearing aid fitting, particularly in cases of asymmetrical word recognition in patients considering unilateral amplification.

Reflecting on the necessity of valid testing, Mark Twain’s quote comes to mind: “Do the right thing. It will gratify some people and astonish the rest.” The clinical utility of word recognition testing hinges entirely on its validity and reliability. This brings us to the essential components of effective clinical word recognition testing, which we’ve distilled into five key areas: appropriate presentation levels, standardized materials, test efficiency, careful interpretation, and avoidance of detrimental practices, notably live voice testing.

Navigating Presentation Levels: HL vs. SL

Gus Mueller: Let’s begin with presentation levels, a critical first step. Ben, are you ready to dive in?

Ben Hornsby: Absolutely, Gus. Let’s start by setting the stage with a real-world scenario.

Mueller: Consider a 55-year-old male, self-referred due to noise exposure from years of unprotected hunting, experiencing self-perceived hearing loss and tinnitus. His audiogram revealed symmetrical hearing loss, descending to 60-75 dB HL in the higher frequencies. A common profile for noise-induced hearing loss. However, at 2000 Hz, there was a 20 dB inter-aural difference: 40 dB HL in the right ear and 60 dB HL in the left. Low-frequency hearing was within normal limits, resulting in SRTs of 10 dB HL bilaterally, consistent with his low-frequency thresholds.

This is a familiar audiogram to many. The audiologist proceeded with word recognition testing using the SRT-plus-40 dB HL method, presenting speech at 50 dB HL to both ears. The results were 96% for the right ear and 80% for the left, a 16% asymmetry. Remarkably, given the hearing loss in the left ear, achieving 80% at 50 dB HL is somewhat unexpected, as much of the speech spectrum would have been inaudible.

Imagine if you were that audiologist, instructing the patient for the poorer ear:

“I will present a list of words. Please repeat them. Many words contain high-frequency sounds essential for understanding. However, I’ve chosen a presentation level that will make these crucial high-frequency components inaudible in your left ear. Consequently, you’ll likely perform poorly, and I will record this score in your chart.”

Absurd, isn’t it? It’s akin to an optometrist deliberately impairing vision during an eye chart test.

Back to the case: Due to the 16% asymmetry, the otolaryngologist, following American Academy of Otolaryngology (AAO) guidelines for asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) – specifically, “a difference between ears in speech discrimination of >15%” – ordered an MRI to rule out retrocochlear pathology. The MRI was, predictably, negative.

Why an MRI for a 16% asymmetry? The guidelines exist, but the methodology used to derive the 16% asymmetry score is questionable in this scenario.

Six months later, at another clinic, word recognition was re-evaluated at 80 dB HL in both ears. Scores improved to 94% in the right and 92% in the left. Why? Because now, the speech signal was audible in the left ear!

This case highlights a critical flaw: why intentionally test speech at a level that guarantees invalid results and potentially triggers unnecessary, costly medical investigations and patient anxiety? Selecting the correct presentation level is not complex; it’s about applying basic audiologic principles correctly. Perhaps, Ben, you can shed light on the research guiding us towards best practices?

Ben Hornsby: Gus, that anecdote is indeed concerning, yet I suspect it’s more prevalent than we acknowledge. The SRT+40 dB HL approach, while seemingly persistent, is fundamentally flawed. Choosing the optimal presentation level is a long-standing question in research. The SRT+40 dB HL method stems from early studies on normal-hearing individuals and those with mild to moderate hearing loss. However, our patient demographics are far broader today.

So, what constitutes the best presentation level? Guthrie and Mackersie’s (2009) research in the Journal of the American Academy of Audiology (JAAA) provides valuable insights. Before discussing their study, let’s review the common approaches and their limitations.

Clinical methods for selecting presentation levels vary widely. The fixed sensation level (SL) approach, using SRT+30 to 40 dB SL, is common. However, as Gus illustrated, for patients with sloping high-frequency hearing loss and good low-frequency hearing, this often results in insufficient audibility for high-frequency speech sounds, hindering optimal performance.

Conversely, in individuals with severe flat losses, SRT+30-40 dB SL could exceed their Loudness Discomfort Level (LDL).

At Vanderbilt, we typically use a fixed Hearing Level (HL) approach, often 75 or 80 dB HL. While ensuring audibility for many, this might surpass LDL for some or be insufficient for those with more severe losses. The Most Comfortable Loudness Level (MCL) approach is another option, testing at the patient’s preferred loudness. However, as Gus pointed out, our goal isn’t comfortable listening, but maximum performance.

Testing near the LDL is also considered, but excessively high levels can be uncomfortable and potentially degrade performance. The key takeaway is that no single method guarantees consistent attainment of a patient’s PB-Max. Testing at multiple levels might be necessary.

Mueller: I concur, and the VA protocols for compensation cases often involve multi-level testing. However, for busy clinicians, this isn’t always practical.

Hornsby: Precisely, which brings us back to Guthrie and Mackersie (2009). They investigated if a single presentation level method could reliably achieve PB-Max. Their question was: if we test at only one level, which method maximizes the chance of reaching maximum performance without exceeding UCL, and does this vary based on hearing loss severity?

They recruited 40 participants with diverse hearing losses, categorized into four groups by audiogram configuration, ranging from steeply sloping to gradually sloping, and varying degrees of severity from mild PTAs (26-40 dB HL) to very severe. They then meticulously measured Performance-Intensity (PI)-PB functions for each participant across multiple levels, in 5 dB steps from SRT+10 dB HL to 5 dB below LDL. This ensured capturing each individual’s maximum performance.

Word recognition was assessed using the Computer Assisted Speech Perception Assessment (CASPA) by Boothroyd (2008). CASPA uses monosyllabic consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words, similar to NU-6 lists, but allows phoneme-level scoring, tripling the scored items per word and enhancing test reliability.

Analyzing the PI-PB functions, they evaluated five presentation level methods. One was a fixed HL of 75 dB HL (95 dB SPL), based on Kamm et al. (1983), who found it likely to reach PB-Max in 75% of mild-to-moderate losses. They also assessed performance at each individual’s MCL, measured using loudness anchors similar to the Cox Contour Test (Hawkins et al., 1987).

Another level was LDL-minus-5 dB HL. The final two methods were sensation level (SL) approaches based on SRT and the 2000 Hz threshold. For SRT-based SL, those with SRTs ≤ 35 dB HL received 35 dB SL presentation (e.g., 70 dB HL or less, depending on SRT). For poorer SRTs, SL was reduced to avoid exceeding LDL. A similar pattern was used for the 2000 Hz threshold-based SL. For significant loss at 2000 Hz, only 10 dB SL was used, increasing slightly with greater loss. They compared scores across these five methods.

The primary finding was that LDL-minus-5 dB HL yielded the highest average scores. The 2000 Hz + SL method was comparable in most cases. These two methods outperformed others in maximizing scores. However, differences between methods varied depending on hearing loss.

For mild losses, all methods performed similarly, logically, as audibility wasn’t a major constraint. In steeply sloping losses, patterns were also similar, except SRT-SL consistently underperformed, failing to provide sufficient audibility. The most significant differences emerged in severe hearing loss. LDL-minus-5 dB HL produced significantly higher scores than all other methods. Fixed HL (75 dB HL) resulted in mean scores around 60% correct, while LDL-minus-5 dB HL yielded approximately 80%. This 20% average difference underscores the importance of sufficient audibility for maximizing word recognition in severe losses. LDL-minus-5 dB HL appeared most effective in achieving this.

Mueller: I recall this study well and its pragmatic approach to a common clinical dilemma. However, the “best” method, LDL-minus-5 dB HL, necessitates an additional test – speech LDL, not routinely performed. It’s arguably the only reason to conduct speech LDLs (Mueller, 2011). Furthermore, LDL measurements can be inconsistent. Relying on LDL for presentation level selection, while theoretically sound, might be clinically cumbersome. The 2000 Hz + SL method, being nearly as effective and based on a standard audiometric measure, seems more practical.

Hornsby: You’re right, LDL measurement adds time. Their results do support 2000 Hz + SL as a highly viable alternative. Crucially, the SRT-SL method consistently underperformed across groups. Fixed SL above SRT often failed to provide adequate audibility, or in some cases, resulted in overly loud presentation.

Mueller: Given our agreement on the 2000 Hz + SL method’s balance of efficiency and accuracy, let’s provide our readers with the specific SL values from Guthrie and Mackersie (2009) for immediate clinical application.

Hornsby: Certainly. Here are the SL values to add to the 2000 Hz threshold to determine the presentation level:

SL values added to 2000 Hz threshold for presentation level:

2000 Hz Threshold <50 dB HL: 25 dB SL

2000 Hz Threshold 50–55 dB HL: 20 dB SL

2000 Hz Threshold 60–65 dB HL: 15 dB SL

2000 Hz Threshold 70–75 dB HL: 10 dB SL

Mueller: Easily memorized, perhaps with a “cheat sheet” initially. The Kamm study you mentioned dates back to 1983, correct?

Hornsby: Yes, 1983.

Mueller: So, for 30 years, we’ve known SRT-SL isn’t optimal. Why is it still prevalent?

Hornsby: Tradition likely plays a role. Practices learned in training often persist. While one hopes SRT-SL isn’t still taught, it’s possible. As mentioned, SRT-SL originated from 1940s research with normal hearing listeners. For them, PB-Max is typically reached within 30 dB SL of SRT. But this doesn’t hold for hearing-impaired individuals.

The Imperative of Standardized Materials

Mueller: Presentation levels addressed; let’s move to standardized materials, a related yet distinct issue.

NU-6 word lists were designed as 50-word lists. Extensive research confirms inter-list equivalency for these 50-word lists, particularly the Auditec of St. Louis recordings. However, the practice of using half-lists (25 words per ear) persists. Is using half of a standardized test acceptable? It’s questionable for blood pressure tests; what about word recognition?

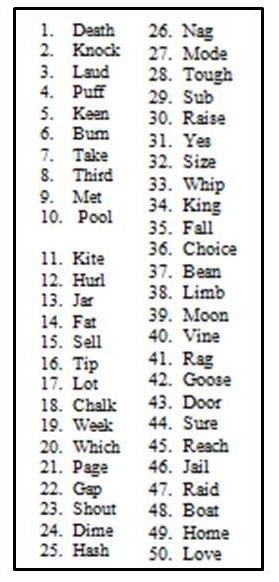

Consider word difficulty variability within lists. Hurley and Sells (2003) rank-ordered NU-6 words by difficulty, revealing significant variation. Some words were missed over 50% of the time, others less than 10%. Figure 1 illustrates this rank ordering for NU-6 List 1.

Figure 1. Ordering of difficulty (hardest to easiest) for the Auditec recording of the NU-6 List 1. Based on the work of Hurley and Sells (2003).

Imagine a patient with mild-to-moderate symmetrical sloping loss and reduced cochlear function, achieving a true PB-Max of 80% bilaterally. Let’s assume they consistently miss the 10 hardest words (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows NU-6 List 1 with the 10 hardest words marked.

Figure 2. Standard ordering of the Auditec NU-6 List 1. The ten most difficult words have been checked.

Using a full 50-word list, both ears would score around 80%. However, with half-lists, consider the potential outcome. Using the first half of List 1 for the right ear and the second half for the left, our hypothetical patient might score 68% (8 misses in the first half, including many difficult words) in the right ear and 92% (2 misses in the second half, fewer difficult words) in the left, a 24% asymmetry. This could trigger unnecessary MRIs or misguide unilateral hearing aid fitting decisions, all due to using half-lists to save minimal time. If time is the primary driver, why not a one-word list?

Ben, what does the research say about half-lists?

Hornsby: Gus, your example is perfectly illustrative. Researchers have indeed investigated this. Beyond Auditec, other NU-6 recordings exist, including Bill Rintelmann’s. Rintelmann et al. (1974) examined the reliability of NU-6 lists from his recordings, comparing 50-word lists to half-lists across normal-hearing, young hearing-impaired, and elderly hearing-impaired groups. Using Lists 2 and 3, 50-word list performance was equivalent, as expected.

However, comparing the first and second 25 words within each list, Rintelmann et al. (1974) found a mean difference of 16 percentage points in the elderly hearing-impaired group – some individuals exhibiting even greater disparities. This trend was present across all groups but most pronounced in the elderly, likely due to poorer overall performance amplifying the impact of word difficulty.

Using half-lists compromises test reliability and list equivalency. NU-6 is designed and normed for 50-word lists. Deviating from this undermines the validity and reliability of results.

Mueller: And smaller sample sizes inherent in 25-word lists further exacerbate variability.

Hornsby: Exactly. Variability in speech testing is influenced by word difficulty and statistical test characteristics. Thornton and Raffin (1978) demonstrated that variability is systematically related to the number of test items and overall score. Clinical word recognition tests provide an estimate of true ability, not a definitive measure. Repeating the test yields another estimate, and with enough words, we approach a more accurate representation of true ability, but variability persists.

Thornton and Raffin (1978) showed that variability increases systematically with scores closer to 50%. For 50-item lists, standard deviation is about 7%; for 25 items, it’s approximately 10% – a 40% increase in variability by halving the list. We’ll revisit this later, but this highlights the impact of item number on variability.

The crucial point is that tests normed for 50 items require 50 items for reliable scoring, especially when comparing scores over time or between ears. Altering the protocol reduces reliability and validity, a poor trade-off for minimal time savings.

Mueller: Thank you, Ben. We’ll indeed return to Thornton and Raffin’s binomial model. Regarding test items, Arthur Boothroyd advocates phoneme scoring for CVC words like NU-6, effectively tripling items. However, data on word difficulty and list equivalency using phoneme scoring is less established.

Hornsby: NU-6 is normed for word scoring, not phoneme scoring. Phoneme scoring, while potentially increasing item count, doesn’t guarantee list equivalency using that metric. The lists are validated based on word-level scoring.

Maximizing Testing Efficiency Without Compromising Accuracy

Mueller: As Benjamin Franklin wisely said, “Time is money.” Clinicians often voice the concern: “University protocols are ideal, but in the trenches, time is limited. Shortcuts are necessary.”

Having spent 25 years in clinical practice, I understand this pressure. Time management in audiology often involves balancing patient volume with service quality. Two approaches exist: fitting patient slots to time constraints, or allocating time based on best-practice procedures. The latter, prioritizing best practice, is the more responsible approach. To save time effectively in speech testing, balance testing, or hearing aid fitting, we must consider:

- Can we shorten procedures without sacrificing validity and reliability?

- Are we providing professionally responsible services commensurate with patient expectations and fees?

Consider also the actual time saved versus the potential cost of compromised accuracy. Returning to half-lists: a 50-word recorded NU-6 list takes about 3 minutes per ear, 6 minutes bilaterally. Half-lists save only 3 minutes per patient. Is this minimal saving worth risking test validity? Ben, research must offer insights into streamlining speech testing efficiently.

Hornsby: Fortunately, test efficiency is a research focus. Inefficient practices should not be standard.

Hurley and Sells (2003) specifically addressed test abbreviation for word recognition. Their aim was a screening protocol to rapidly identify patients with excellent word recognition (≥ 94%). For those with poorer performance, thorough assessment is crucial for accurate ability estimation.

Their research confirmed that yes, efficient screening is possible. We can distinguish excellent word recognition from poorer performance using the most difficult words from the lists (Figure 1). If a patient correctly identifies the most difficult words, they are highly likely to correctly identify easier words, allowing for test termination.

The question then becomes: what protocol identifies patients needing the full 50-word list? For poorer performers (e.g., 50% correct), accurate score determination necessitates full lists. For near-perfect performers, precise scores (96%, 98%, 100%) are less clinically relevant. Hurley and Sells (2003) used Auditec NU-6 recordings (50-word lists, four forms) to develop their protocol. They tracked word recognition scores and individual word errors to determine word difficulty. They then ordered lists by difficulty (Figure 1).

These ordered lists were used to re-score patient performance, evaluating if using the 10 most difficult words could predict scores ≥ 94% on 50-word lists. Figure 3 shows the error rates for the 25 most difficult words in NU-6 List 1. “Death” had a 66% error rate, while “pool” had 42% for the 10th most difficult word and “hash” (25th) 29%. “Love” was surprisingly the easiest, with only a 4.5% error rate.

Figure 3. Top 25 most difficult words from NU-6 List 1, in order of error rate (adapted from Hurley & Sells, 2003).

Mueller: Ben, “love” easiest and “death” hardest? Perhaps Dr. Phil should interpret that!

Hornsby: Intriguing, indeed. Word recognition extends beyond simple audibility.

Using Clinical Decision Analysis, Hurley and Sells (2003) evaluated 10-word and 25-word screening tests (Figure 4). The 10-word test rule was: “Miss zero or one word in the first 10 (most difficult) words = pass.” Failing meant needing further testing. Figure 4 illustrates potential outcomes.

Figure 4. Clinical Decision Analysis used by Hurley and Sells (2003) to determine effectiveness of word recognition screening tests.

Testing over 400 participants, they found a serial positive protocol highly effective for identifying those scoring below 96%. Their efficient screening rules:

- Present the 10 most difficult words. 0-1 miss: stop testing for that ear. Unlikely to score < 96% on 50 words.

- > 1 miss on 10 words: present the next 15. Total 25 words, ≤ 3 misses: stop testing.

- > 3 misses on 25 words: administer full 50-word list.

This protocol correctly identified all participants scoring below 96% (100% sensitivity). In their sample, 25% didn’t need the full 50-word list, potentially saving over an hour per 10 patients.

Mueller: Many clinics already use this, but it’s a valuable reminder. Efficiency without sacrificing accuracy is possible. Crucially, this protocol is validated only for Auditec NU-6 recordings. Live voice testing negates its validity.

Hornsby: Correct. The ordered list is “Auditec NU-6 Ordered by Difficulty (Version II).” A different ordered list exists from Auditec; differentiation is vital.

Mueller: Using this NU-6 version has no downside. Worst case: full 50 words, which you’d have done anyway. And use the shortened-interval version for optimal pacing. Moving on…

Discerning Real Differences: Statistical Significance in Word Recognition Scores

Mueller: Returning to the ENT clinic case: a 16% inter-ear difference leading to MRI referral. Is a 16% difference clinically significant? Probably not. But when is a difference real? Clinicians often need to determine if one ear truly performs better than the other. Patients ask: “Do I hear better in one ear?” We need statistically sound answers. A few percentage points are clearly insignificant, but what threshold indicates a genuine difference? For unilateral hearing aid fitting, true inter-ear differences in word recognition might guide ear selection. But we must ensure observed differences are not due to test unreliability.

Ben, what guidance can you offer on statistically significant differences?

Figure 5. Sample patient’s audiogram. This patient had word recognition scores of 68% in the right ear and 44% in the left ear.

Hornsby: Indeed, Gus. Consider this sample patient (Figure 5). Symmetrical thresholds, but word recognition scores at 75 dB HL (50-word lists) are 68% right ear, 44% left. Is this a real difference? Statistical methods, rooted in test-retest variability, can help.

Mueller: Are we revisiting the binomial model?

Hornsby: Yes, Thornton and Raffin (1978). Not light reading, but clinically crucial for interpreting scores. Variability depends on item number and true ability; scores near 50% are most variable. Statistical models can predict variability around true scores.

Thornton and Raffin (1978) developed critical difference tables – readily accessible and clinically invaluable. These tables show 95% critical differences for given scores and item numbers. They indicate the score range expected due to chance variability.

Mueller: To simplify, Figure 6 adapts the Thornton and Raffin table. While 25-word lists are suboptimal, their critical differences are included for emphasis.

Figure 6. The critical differences (.05 level of confidence) adapted from Thornton and Raffin (1978) that can be used for comparison of two word recognition scores. Select one of the two scores and find this score on the vertical columns which go from 0 to 100%. To the right of each one of these values there is a range of scores for either a 25-word or 50-word list. If the second test score falls within this range, this score is not different from the first score.

Hornsby: Thank you, Gus. Our patient’s left ear score is 44%. What’s the expected range if true ability is 44%? For 25-word lists, the range is 20%-68% (Figure 6). Scores outside this range ( <20% or >68%) have only a 5% chance of being statistically indistinguishable from 44%. The right ear score is 68%. While 44% and 68% seem different, with 25-word lists, we’d conclude they are not statistically different.

Increasing items reduces variability. For 50-word lists, the critical difference range for 44% shrinks by 12%, to 26%-62%. Now, with 50 words, the 68% right ear score falls outside this range. We can confidently conclude the scores are statistically different, not due to chance.

Carney and Schlauch (2007) replicated Thornton and Raffin (1978) using computer simulations, confirming their accuracy with minor differences. They also published updated critical difference tables.

Mueller: We’ve discussed inter-ear comparisons, but these tables also assess score changes over time with consistent word lists. Or, as mentioned, inform hearing aid fitting decisions. Students often mistakenly assume small percentage differences (6%, 10%) are meaningful. Jerry Studebaker’s calculations illustrate this.

Hornsby: From his 1982 Vanderbilt Hearing Aid Report?

Mueller: Exactly. To achieve 6% significance (p<.05), 376 words are needed; for 10%, 135 words. For a 2% difference to be significant, a staggering 3381 words are required. We must accept the larger ranges in Thornton and Raffin’s table.

Hornsby: 3381 words? Equivalent lists and patient endurance would be major hurdles!

Careful Interpretation: Contextualizing Word Recognition Findings

Mueller: Interpreting 50-word NU-6 scores often involves assessing “normality.” Is a score expected for a given hearing loss?

Hornsby: Back to Figure 5: 68% right ear, 44% left. Are these PB-Max for this loss? Remember, presentation level significantly impacts scores.

Figure 7. Sample audiogram with LTASS (speech banana, shaded yellow portion is audible, the purple portion is not) that roughly corresponds to a 75 dB HL presentation level.

Figure 7 shows the Long-Term Average Speech Spectrum (LTASS) or speech banana overlaid on the audiogram at 75 dB HL. Much of the high-frequency speech spectrum is inaudible. We might expect suboptimal performance. Increasing level to 100-105 dB HL (Figure 8) improves audibility, potentially raising scores. But are 68% and 44% truly PB-Max? Can we estimate PB-Max without extensive multi-level testing?

Figure 8. Sample audiogram with LTASS (speech banana, shaded yellow portion is audible, the purple portion is not) that roughly corresponds to a 100-105 dB HL presentation level.

Judy Dubno’s group at the Medical University of South Carolina addressed this, developing “confidence limits for maximum scorers” (Dubno et al., 1995). They defined the lower limit of “normal” word recognition scores for given hearing losses. Scores below this limit suggest abnormally low performance, prompting re-evaluation of presentation level to ensure PB-Max is reached.

Mueller: Lower scores could also reflect auditory processing or cognitive deficits, even at PB-Max.

Hornsby: Valid point. But first, confirm PB-Max. Dubno et al. (1995) measured word recognition (Auditec NU-6) at multiple levels to determine PB-Max in 400 adults with cochlear hearing loss. Using this data and simulations, they established lower confidence limits.

They calculated 95% confidence intervals – 5% of scores fall below this limit. Scores poorer than this cutoff, for a given PTA, are likely abnormally low, suggesting potentially unreached PB-Max. They provided a table in their article (Dubno et al., 1995). Gus, do you have that chart?

Mueller: Close. Dubno’s data can be less accessible, but Linda Thibodeau streamlined it. Her chart, Figure 9, is invaluable. Ben, please explain.

Figure 9. SPRINT chart for 50-word recorded Auditec lists. To examine the 95% confidence limit for PB-Max on the Auditec NU#6 list, determine the intersection of the word recognition score on the top x-axis, and the patient’s PTA on the left y-axis. If the intersection of these two values falls within the shaded area, the word recognition score is considered disproportionately low (based on the work of Dubno et al., 1995). This is illustrated with the red arrows. To examine the 95% critical difference for two word recognition scores, determine the intersection of the first (bottom x-axis) and the second (right y-axis) score. If the intersection point falls within one of the vertical arrows, the two scores are not significantly different from each other (based on work of Thornton and Raffin, 1978). This is illustrated with the blue arrows. The SPRINT chart is reproduced here with permission from the developer, Linda Thibodeau, PhD (Thibodeau, 2007).

Hornsby: Linda Thibodeau’s (2007) SPRINT chart (Speech Recognition INTerpretation) (Figure 9) integrates Dubno et al. (1995) and Thornton and Raffin (1978) data for 50-word lists.

The shaded area represents Dubno’s 95% confidence limits for PB-Max. Scores within this area are “disproportionately low.” The left axis is PTA (500, 1000, 2000 Hz), descending from 0 dB HL. Our sample patient’s left ear PTA is 51.7 dB HL. Top axis: word recognition score (44%). Red arrows in Figure 9 show the intersection falling within the shaded area. Thus, 44% is disproportionately low, suggesting retesting at a higher level.

For Thornton and Raffin’s critical differences, disregard the shaded area and focus on vertical arrows. Bottom x-axis: first score; right y-axis: second score. Arrows indicate 95% critical difference range. Left ear 44%, right ear 68%. Intersection (blue arrows, Figure 9) falls outside the vertical arrows. These scores are statistically different.

The SPRINT chart simplifies interpretation of word recognition results.

Mueller: Indispensable tool! For readers, Dr. Thibodeau generously provided the SPRINT chart for 50-word lists as a handout: download the SPRINT chart for 50-word lists here.

Ben, accurate reporting and patient counseling are impossible without this data.

Hornsby: Absolutely essential.

Stop The Madness: Banishing Live Voice Testing

Mueller: Our final category addresses a persistent, detrimental practice: live voice word recognition testing. Roeser and Clark (2008) aptly titled their article on this, Stop the Madness.

Reasons for using live voice are often dubious. One audiologist cited: “My docs won’t buy a CD player.” A $100 CD player is a trivial cost compared to compromised best practice.

Unfortunately, this isn’t isolated. Finan (2012) surveyed AAA members across the US. Disturbingly, 58% reported using live voice for speech recognition. Do they also whistle pure tones instead of calibrated signals?

Tolstoy’s quote resonates: “Wrong does not cease to be wrong because the majority share in it.” Ben, we hadn’t planned to address this, but these survey results necessitate it.

Hornsby: Those survey results are indeed perplexing. Evidence strongly opposes live voice. Why deviate from best practice and risk misdiagnosis? Some claim live voice is faster and more flexible. But how much time, and at what cost? Data exists on time savings.

Mendel and Owen (2011) in International Journal of Audiology compared live voice to recorded (Auditec CDs, 50-word lists, unordered). They used Auditec CDs with 4-second and 2.5-second inter-word intervals, comparing them to monitored live voice across young normal-hearing and older hearing-impaired adults.

Time difference? Less than a minute per 50-word list for live voice versus recorded. For hearing-impaired adults, recorded testing was only 49 seconds longer per ear. Minimal time saving for live voice.

Mueller: 49 seconds per ear, roughly two minutes per patient for valid, reliable results. An easy choice. Furthermore, computer-based audiometers allow mouse-click-paced recorded testing, likely matching live voice speed.

Hornsby: Time is a minor factor; validity and reliability are paramount. The words are not the test; the recorded version is. Live voice testing is essentially a test of the examiner, variable with each presentation, significantly reducing reliability and interpretability.

This has been known for decades. Bess (1983) compiled PI functions for recorded NU-6 from different recordings. Talker variability is significant. For Tillman’s (1966) original NU-6 recording, 8 dB SL yielded 75% average score. Beattie’s (1977) recording of the same list at 8 dB SL yielded only 15% – a 60% difference due to talker.

Mueller: And these are professional recordings. Live voice variability is likely greater.

Hornsby: Again: THE WORDS ARE NOT THE TEST! Recorded stimuli are essential for interpretable results. Consider our 68% vs. 44% scores. Interpreting these using statistical models requires test consistency, which live voice lacks. Thornton and Raffin (1978) and Dubno et al. (1995) data are inapplicable to live voice testing. Live voice renders interpretation of score differences, changes over time, and normality assessments impossible. Clinically unacceptable.

Mueller: And the 10-word screening test is also invalidated – no known “most difficult words” for live voice. Ironically, live voice, intended to save time, prevents using time-saving protocols.

Ben, you’ve thoroughly reviewed literature, background, and procedures for clinical speech testing, a cornerstone of audiology.

Summary

Let’s summarize key takeaways:

Things To Do

- Always use recorded materials. Shortened-interval Auditec NU-6 recommended.

- Optimize presentation level for audibility without discomfort. UCL-minus-5 dB HL or 2000 Hz-SL method.

- Use Thornton and Raffin data for statistically significant differences. SPRINT chart (Thibodeau) includes this.

- Use Dubno data to assess “normalcy” of scores. SPRINT chart (Thibodeau) includes this.

- Use Ordered-By-Difficulty Auditec NU-6 and 10-word/25-word screenings.

Things Not To Do

- Live-voice testing.

- SRT+30 or SRT+40 dB HL presentation level.

- Randomly assess score differences.

- Half-list testing (except with Ordered-By-Difficulty screening).

Question & Answer

Mueller: Ben, before audience questions: computer-based audiometers using audio files instead of Auditec CDs – is research on CD versions applicable?

Hornsby: A valid concern. File compression for digital audio (MP3s, etc.) raises questions. Compression algorithms discard data to reduce file size. Acceptable for music, but potentially problematic for clinical testing.

Vanderbilt doctoral student Jodi Rokuson (2012) investigated this. She used advanced audio coding (AAC) compression at 64 KB per second – a high-compression algorithm. If issues weren’t found with this, less aggressive compression would likely be safe.

Testing over 160 ears, she compared original Auditec CDs to compressed versions. AAC compression is designed to be perceptually indistinguishable. And indeed, no significant score differences were found. Compressed files, even with aggressive algorithms, appear clinically equivalent to original CDs.

Mueller: Reassuring. Audience questions?

If using high-intensity word recognition, what contralateral masking is recommended?

Hornsby: Routine masking is essential. Many audiometers automatically apply masking 30 dB below presentation level, tracking level changes. This works for cochlear losses with < 30 dB inter-aural difference. For larger conductive components in the non-test ear, adjust masking accordingly. Crossover applies to speech as well as pure tones.

Pediatric populations? UCL finding is challenging. SPRINT chart for PBK?

Hornsby: Pediatrics is a specialized area, not my expertise. No SPRINT chart for PBK. Audibility remains key. Aim for comfortably loud levels, perhaps estimating comfort level during interaction. Pure-tone thresholds can guide 2000 Hz-SL method application.

CASPA routine use, word and phoneme scoring reported. Which is preferred if only one?

Hornsby: Phoneme scoring might be statistically more robust due to increased item count. However, NU-6 is normed on word scoring. Clinical reporting should align with established norms. For test-retest reliability comparisons, phoneme scores might be more sensitive due to reduced variability.

Studies on phonemic awareness/speech sound recognition training improving word recognition?

Hornsby: Active research area with some positive findings. Generalization of training gains to untrained materials remains a challenge. Ongoing research, including larger clinical trials and longitudinal studies, is needed. Premature to make strong claims about magnitude of improvement currently.

Optimal presentation level for rising or low-frequency hearing losses? Studies?

Hornsby: Limited research on this specific configuration. Audibility remains crucial. High presentation levels ensure low-frequency sound audibility. However, reverse-slope losses can be associated with cochlear dead regions, where high levels can degrade performance.

SPRINT chart for W-22 lists?

Hornsby: Partially applicable. Thornton and Raffin (1978) data (critical differences) are statistically based and applicable to any reliable speech test, including potentially W-22 if lists are equivalent. Dubno et al. (1995) data (confidence limits) are NU-6 specific. W-22 PI functions differ slightly from NU-6, so Dubno’s data is less directly applicable to W-22.

Word count for aided/unaided sound field testing presentation levels?

Hornsby: Depends on testing goals. For conversational speech estimation, test at conversational levels (40-50 dB HL sound field, calibrated). For demonstrating aided benefit, softer levels might be more effective. Thornton and Raffin (1978) rules apply to sound field as well as headphones for statistical comparisons, but demonstrating significant aided benefit can be challenging due to variability. Softer speech levels may better highlight aided vs. unaided differences.

References

Beattie, R. C., Edgerton, B. J., & Svihovec, D. V. (1977). A comparison of the Auditec of St. Louis cassette recordings of NU-6 and CID W-22 on a normal-hearing population. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 42, 60-64.

Bess, F. (1983). Clinical assessment of speech recognition. In D. F. Konkle & W.F. Rintelmann (Eds.), Principles of speech audiometry (pp. 127-201). Baltimore: University Park Press.

Boothroyd, A. (2008). CasperSent: A program for computer-assisted speech perception testing and training at the sentence level. Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology,41, 31-52.

Carney, E., & Schlauch, R. S. (2007). Critical difference table for word recognition testing derived using computer simulation. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 1203-1209.

Dubno, J. R., Lee, F. S., Klein, A. J., Matthews, L. J., & Lam, C. F. (1995). Confidence limits for maximum word-recognition scores. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38(2), 490-502.

Finan, R. (2012). Survey of audiometric practices in the United States (Unpublished Capstone project). University of Northern Colorado, Greely, CO.

Guthrie, L. A., & Mackersie, C. L. (2009). A comparison of presentation levels to maximize word recognition scores. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 20(6), 381- 390.

Hawkins, D. B., Prosek, R. A., & Walden, B. E. (1987). Binaural loudness summation in the hearing impaired. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 30, 37-43.

Hurley, R. & Sells, J. (2003). An abbreviated word recognition protocol based on item difficulty. Ear and Hearing, 24(2), 111-118.

Kamm, C. A., Morgan, D. E., & Dirks, D. D. (1983). Accuracy of adaptive procedure estimates of PB-max level. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 202-209.

Mendel, L. & Owen, S. (2011). A study of recorded versus live voice word recognition. International Journal of Audiology, 50(10), 688-693.

Mueller, H.G. (2011). How loud is too loud? Using loudness discomfort measures for hearing aid fitting and verification, part 1. AudiologyOnline, Article 825. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com.

Rintelmann, W. F., Schumaier, D. R., Jetty, A. J., Burchfield, S. B., Beasley, D. S., Mosher, N. A.,…Penley, E. D. (1974). Six experiments on speech discrimination utilizing CNC monosyllabic words (Northwestern University Auditory Test No. 6). Journal of Auditory Research, 2(Suppl), 1-30.

Roeser, R. J., & Clark, J. L. (2008). Live voice speech recognition audiometry – Stop the madness. Audiology Today, 20(1), 32-33.

Rokuson, J. (2012). Testing word recognition on patients in an audiology clinic using uncompressed and compressed audio coding formats. (Unpublished Capstone project). Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Studebaker, G. (1982). Hearing aid selection: An overview. In G. Studebaker and F. Bess (Eds.), The Vanderbilt hearing aid report (pp. 147-160). Upper Darby, PA: Monographs in Contemporary Audiology.

Thibodeau, L. M. (2007). Speech audiometry. In R. Roeser, M. Valente, and H. Hosford-Dunn (Eds.), Audiology: Diagnostics (pp. 288-313). New York: Thieme Medical Publishers.

Thornton, A., & Raffin, M. (1978). Speech-discrimination scores modeled as a binomial variable. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 21(3), 507-518.

Tillman, T. W., & Carhart, R. (1966). An expanded test for speech discrimination utilizing CNC monosyllabic words, Northwestern University Auditory Test No. 6. Technical Report No. SAM-TR-66-55(June), 1-12.

Cite this content as:

Hornsby, B., & Mueller, H.G. (2013, July). Monosyllabic word testing: Five simple steps to improve accuracy and efficiency. AudiologyOnline, Article #11978. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/