Active and passive transport are fundamental biological processes that govern how substances move across cell membranes. These processes are essential for cell survival, enabling the uptake of nutrients and the expulsion of waste products. While both active and passive transport facilitate the movement of molecules, they differ significantly in their energy requirements and the direction of movement relative to the concentration gradient. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for grasping the intricacies of cellular biology.

Deciphering the Core Differences Between Active and Passive Transport

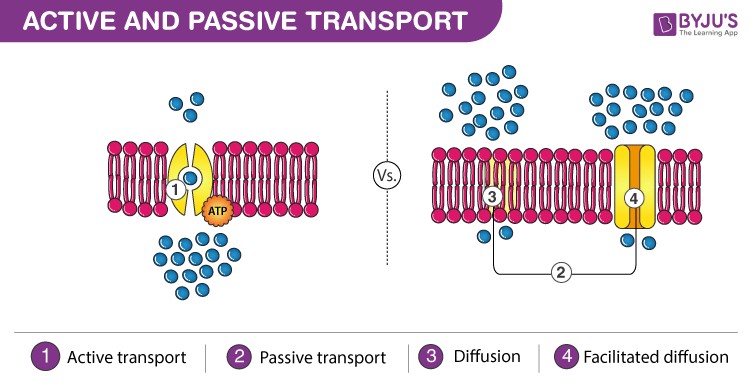

The primary distinction between active and passive transport lies in the utilization of cellular energy. Active transport, as the name suggests, necessitates cellular energy, typically in the form of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), to move molecules against their concentration gradient. Conversely, passive transport is an energy-free process that relies on the inherent kinetic energy of molecules to move them down their concentration gradient.

Here’s a detailed comparison highlighting the key differences:

| Feature | Active Transport | Passive Transport |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Requirement | Requires cellular energy (ATP) | Does not require cellular energy |

| Concentration Gradient | Moves molecules against the concentration gradient (low to high concentration) | Moves molecules along the concentration gradient (high to low concentration) |

| Direction of Movement | Unidirectional (typically) | Bidirectional |

| Selectivity | Highly selective, often involves carrier proteins or pumps | Can be selective or non-selective, depending on the type |

| Rate of Transport | Generally faster, can be saturated | Comparatively slower |

| Temperature Dependence | Significantly influenced by temperature | Less influenced by temperature |

| Oxygen Dependence | Reduced oxygen levels can inhibit active transport | Not affected by oxygen levels |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Inhibited by metabolic inhibitors | Not affected by metabolic inhibitors |

| Carrier Proteins | Always involves carrier proteins or pumps | May or may not involve carrier proteins (e.g., simple diffusion vs. facilitated diffusion) |

| Examples | Sodium-potassium pump, endocytosis, exocytosis, nutrient uptake in roots | Simple diffusion, osmosis, facilitated diffusion, gas exchange in lungs |

| Purpose | Establishing and maintaining concentration gradients, uptake of essential nutrients against gradient, waste removal against gradient | Maintaining equilibrium, transport of small, nonpolar molecules, water transport, transport of polar molecules down gradient |

Active Transport: Pumping Molecules Against the Tide

Active transport is a dynamic process that empowers cells to accumulate substances even when their concentration is higher inside the cell than outside. This “uphill” movement against the concentration gradient requires energy input. Think of it like pushing a ball uphill – you need to exert energy to overcome gravity. In cells, this energy is typically provided by ATP hydrolysis, which fuels specialized protein pumps embedded within the cell membrane.

There are two main categories of active transport:

-

Primary Active Transport: This type directly utilizes ATP hydrolysis to power the movement of molecules. A prime example is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ pump), which is crucial for maintaining cell membrane potential and nerve impulse transmission. This pump actively moves sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell and potassium ions (K+) into the cell, both against their respective concentration gradients, using the energy from ATP.

-

Secondary Active Transport: This type indirectly utilizes energy, harnessing the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport. It’s like using the downhill flow of water (created by pumping water uphill – primary active transport) to turn a water wheel. For instance, the sodium-glucose cotransporter uses the sodium gradient (created by the Na+/K+ pump) to transport glucose into the cell, even against the glucose concentration gradient.

Processes like endocytosis (bringing substances into the cell by engulfing them in vesicles) and exocytosis (releasing substances out of the cell by fusing vesicles with the plasma membrane) are also forms of active transport, as they require energy to manipulate the cell membrane and transport large molecules or particles.

Passive Transport: Going with the Flow

Passive transport, in contrast, is a spontaneous process that doesn’t demand cellular energy. It relies on the second law of thermodynamics, where systems tend towards greater entropy, meaning molecules naturally move from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration to achieve equilibrium. This “downhill” movement is akin to a ball rolling downhill – it occurs naturally due to gravity, without any external energy input.

Passive transport encompasses several mechanisms:

-

Simple Diffusion: This is the most straightforward form of passive transport, where small, nonpolar molecules like oxygen, carbon dioxide, and lipid-soluble substances directly pass through the cell membrane down their concentration gradient. The membrane acts as a selective barrier, but for these molecules, it’s relatively permeable.

-

Facilitated Diffusion: For larger or polar molecules that cannot easily cross the lipid bilayer, facilitated diffusion comes into play. This process utilizes channel proteins or carrier proteins embedded in the membrane to assist the movement of these molecules down their concentration gradient. These proteins act like selective tunnels or revolving doors, speeding up the diffusion process without requiring energy. Examples include glucose transporters (GLUTs) that facilitate glucose uptake into cells.

-

Osmosis: This is the diffusion of water across a semipermeable membrane from an area of higher water concentration (lower solute concentration) to an area of lower water concentration (higher solute concentration). Osmosis is crucial for maintaining cell volume and hydration. Water moves to equalize solute concentrations on both sides of the membrane.

Key Takeaways: Active and Passive Transport in Harmony

Both active and passive transport are indispensable for cellular life, working in concert to maintain cellular homeostasis and carry out essential functions. While active transport allows cells to concentrate specific substances and move them against their natural flow, passive transport efficiently handles the movement of other molecules, particularly those moving down their concentration gradients.

Understanding the nuances of active and passive transport is fundamental to comprehending a wide range of biological processes, from nutrient absorption and waste removal to nerve signaling and muscle contraction. These processes are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary, ensuring the dynamic and efficient exchange of materials across cell membranes, which is the very essence of life at the cellular level.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: In simple terms, how can I remember the difference?

A: Think of it like this: Active transport is like pushing a swing uphill – it needs energy. Passive transport is like letting the swing go downhill – it happens naturally without energy.

Q2: Is facilitated diffusion considered active or passive transport?

A: Facilitated diffusion is a type of passive transport. Although it involves carrier proteins, it does not require cellular energy. The molecules still move down their concentration gradient, and the proteins simply facilitate this movement.

Q3: What would happen if active transport stopped working in a cell?

A: If active transport ceased, cells would lose their ability to maintain concentration gradients for essential molecules. Nutrient uptake against the gradient would stop, waste removal might be impaired, and vital processes like nerve impulse transmission (dependent on the Na+/K+ pump) would be disrupted, ultimately leading to cell dysfunction and death.

Q4: Can a molecule use both active and passive transport to cross the membrane?

A: Yes, depending on the cell’s needs and the molecule’s properties. For example, glucose can enter cells via facilitated diffusion (passive) when glucose levels are high outside the cell. In other cases, or in different cell types, active transport mechanisms might be used for glucose uptake, especially when needing to absorb every last molecule even against a gradient.

Q5: Are viruses transported into cells via active or passive transport?

A: Viruses often exploit cellular mechanisms to enter cells, and this can involve processes that resemble or hijack both active and passive transport pathways. For example, some viruses enter through receptor-mediated endocytosis (which is a form of active transport), while others might utilize membrane fusion mechanisms that have passive aspects. Viral entry mechanisms are complex and virus-specific.