Violin making, much like composing or performing music, blends structure with artistry. For musicians, the structure comes from the score, the notes laid out on the page. For violin makers, it’s in the precise specifications of the instrument itself, with variations typically within mere millimeters. In both disciplines, interpretation is key. However, within the structured world of violin creation, certain elements offer a space for improvisation and personal expression, much like a cadenza in a classical piece.

Two such elements stand out: the scroll and the f-holes. While bound by parameters as strict as any other part of the violin, these are areas where the maker’s artistry truly emerges. It’s a departure from pure measurement, a journey from a defined starting point to a precise endpoint, with room for improvisation in between. This is where the violin maker can introduce a personal “cadenza,” an eight-bar break within strict rules of key, tempo, and tune, yet uniquely their own.

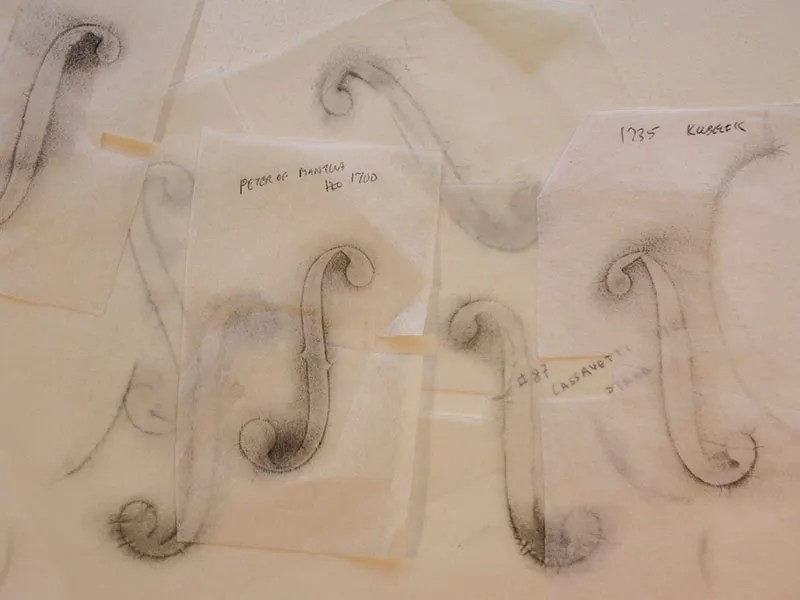

With f-holes, however, this spontaneity can be subtle. The vast majority of violins we see today are copies, often modeled after renowned instruments by Stradivari, Guarneri, Maggini, Goffriller, or Montagnana. For centuries, templates have been the norm, with the objective, as taught in many schools, being to precisely replicate a pre-determined line. The result is f-holes that are mirror images of each other, and often strikingly similar across different instruments of the same model.

This uniformity, however, stands in stark contrast to the approach taken by classical makers, particularly the Italian masters of the Golden Period. Comparing a genuine Stradivarius to a typical French copy reveals a crucial difference: one feels alive, the other static. On a Stradivarius, the f-holes possess a subtle asymmetry, akin to the eyes in a face – they match, but they are not identical. In contrast, the f-holes on many mass-produced violins, especially older French copies, often appear as perfect mirror images, creating an almost unsettling uniformity, much like the identical twins captured in Diane Arbus’s photographs.

This distinction highlights a fundamental aspect of violin making: the maker’s vision. While a musician interprets a score, a violin maker interprets the very essence of the instrument. The author, while not a musician himself, is a devoted listener and understands that the magic between written notes and performed music mirrors the subtle yet profound difference between simply looking at a piece of wood and truly seeing the potential violin within.

“Cutting spruce across the grain dramatically affects the way it moves, so if you turn the upper eyes in, you effectively double the amount of cut wood.”

The iconic shape of the f-hole itself can be deceptively simple, a familiar double-tailed swallow with rounded ends. The upper and lower halves echo each other, and in well-executed f-holes, the curves flow seamlessly, like a skater’s pirouette – a fluid motion where no single point abruptly catches the eye. This inherent beauty can be so captivating, particularly for a violin maker, that it’s easy to overlook the subtle variations that truly bring an f-hole to life. Perhaps it’s not quite the Venus de Milo in universal appeal, but for those who appreciate the craft, the f-holes hold a similar enigmatic allure. Adding to this mystique is their seemingly sudden appearance in the history of stringed instruments. Earlier instruments, like the rebec or gamba family members, used C-holes. The innovation of turning the upper eye of the C-hole inward to create the F-hole was a stroke of genius.

The reason behind this transformation is key to understanding the violin maker’s perspective. Throughout the evolution of musical instruments, especially stringed ones, a driving force has been the pursuit of greater sound – more projection, power, and edge. As concert halls grew larger, orchestras expanded, and audiences became more demanding, composers and conductors pushed for instruments that could fill these spaces.

Violin making represents an unbroken lineage stretching back half a millennium, to the High Renaissance. A shared imperative connects contemporary makers to their historical predecessors: responding to these ever-evolving demands for sound. The author has witnessed this evolution firsthand, observing the revolution in violin strings from gut to tungsten – a clear example of technology adapting to musicians’ needs. It’s conceivable that a musician in Andreas Amati’s time requested an instrument that could simply “turn it up to 11.”

Just as a musician reads notes and perceives phrases, themes, and dynamics, synthesizing them into music, a violin maker looks at a violin and sees an amplifier. The choice of woods, the arching of the plates, the f-holes, the varnish – all are components meticulously chosen and assembled to create a powerful and nuanced sound. However, the f-holes themselves are not the sole determinant of sonic character; rather, it’s the surrounding wood and how it interacts with their shape and placement that truly matters.

Consider the sound of a gamba – refined, elegant, perfectly suited for intimate settings. Now, imagine a maker seeking to create an instrument with a quantum leap in volume and projection. One might consider replacing the flat back with bracing with an arched back, transforming it into a resonant trampoline for the soundpost, significantly amplifying its impact. Equally crucial is enhancing the top’s flexibility. Spruce, when cut across the grain, becomes considerably more responsive. By turning the upper eyes of the f-holes inwards, the maker effectively doubles the amount of wood cut across the grain in a critical area of the top plate.

This consideration of top plate movement is paramount when designing a violin, viola, or cello pattern. The maker carefully determines the placement of the f-hole eyes and the overall width across the “chest” of the instrument, where the bridge will be positioned.

The actual f-hole shape then becomes a matter of connecting these points with elegant curves. However, even in this seemingly purely aesthetic step, the movement of the top plate remains a guiding principle. More slanted f-holes generally result in a stiffer top. Ultimately, it’s the wood between the f-holes, and specifically the width of the cut wood between the inner edge of the upper eye and the outer edge of the lower eye, that significantly impacts the instrument’s voice.

Surprisingly, the overall length or width of the f-hole itself appears to have a less pronounced effect on the sound. While f-hole shapes vary and often serve as a maker’s signature, their dimensions are remarkably consistent. Detailed measurements of numerous Golden Period Italian instruments reveal f-holes within a few millimeters of each other in size, even on cellos, which can vary considerably in body dimensions. Furthermore, no direct correlation has been found between f-hole aperture size and an instrument’s power or timbre; both narrower and wider f-holes can produce exceptional results. The complex interplay of numerous factors contributes to a violin’s sound, making it challenging to isolate the impact of any single element.

The process of creating f-holes begins with marking the position of the eyes, guided by the lower corner and the narrowest point of the c-bout. These markings are made on the inside of the instrument to avoid marring the delicate spruce of the finished arch. Pilot holes are drilled for the upper and lower eyes, followed by specialized cutters to create the actual holes. A template is then used to connect these holes, and a fine jeweler’s saw is employed for the rough cut.

From this point onward, the maker embarks on a journey of improvisation. It’s time to let the curves emerge, to play off each other, to expand and converge, subtly refining the shape until there is no more wood to remove. This entire process is executed with a knife, meticulously shaped and honed to an incredibly sharp edge, enabling smooth cuts through the varying densities of the spruce grain. The final, precise cut of the notches – indicating the bridge’s position – serves as a definitive punctuation, anchoring the f-holes in place.

And just as a musical improvisation reaches its natural conclusion, the creation of the f-holes is complete. Despite countless repetitions, each set emerges with subtle differences, possessing a unique character. They are both familiar and new, a homecoming that is never quite the same, yet always recognizably and beautifully so.

This article originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Strings magazine.

Instrument-Care Basics—Advice from the Experts

A Guide to Choosing the Right Violin Strings

The Characteristic of a Great Restorer’s Work Is Invisibility