Cells, the fundamental units of life, are broadly categorized into two distinct types: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. Prokaryotic cells, characteristic of Bacteria and Archaea, are predominantly single-celled organisms distinguished by their simplicity. In contrast, eukaryotic cells, which constitute animals, plants, fungi, and protists, are more complex and organized. Understanding the differences and similarities between these cell types is crucial in biology. This article will delve into a detailed compare and contrast of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, highlighting their structural components, organization, and size.

Prokaryotic Cells: Simplicity and Efficiency

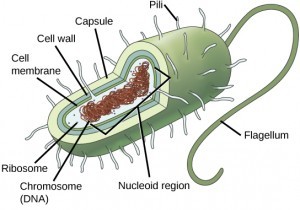

Prokaryotic cells are defined by their lack of a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. This absence of internal compartmentalization is a key feature that distinguishes them from eukaryotic cells. The term “prokaryote” itself, derived from Greek, signifies “before nucleus,” reflecting their evolutionary precedence. Despite their simplicity, prokaryotes are incredibly diverse and adaptable, thriving in a wide range of environments.

Components of Prokaryotic Cells

All cells, regardless of their type, share fundamental components, and prokaryotic cells are no exception. These include:

- Plasma Membrane: An outer boundary that encloses the cell, separating its internal environment from the external surroundings. This membrane regulates the passage of substances into and out of the cell.

- Cytoplasm: A gel-like substance within the cell membrane that houses all the cellular components. Biochemical reactions essential for life occur within the cytoplasm.

- DNA: The genetic material of the cell, carrying the instructions for cell function and reproduction. In prokaryotes, DNA is typically a single circular chromosome and is located in a region called the nucleoid, which is not enclosed by a membrane.

- Ribosomes: Essential for protein synthesis, these particles are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm.

While lacking membrane-bound organelles, some prokaryotes may have additional structures that enhance their survival and function:

- Cell Wall: A rigid outer layer that provides structural support and protection to the cell. In bacteria, the cell wall is composed of peptidoglycan, a unique polymer of sugars and amino acids.

- Capsule: A polysaccharide layer outside the cell wall in some bacteria, aiding in attachment to surfaces and providing additional protection against dehydration and immune responses.

- Flagella, Pili, and Fimbriae: Surface appendages that facilitate movement (flagella) and attachment to surfaces or other cells (pili and fimbriae). Pili can also be involved in conjugation, a process of genetic material exchange between bacteria.

Eukaryotic Cells: Complexity and Compartmentalization

Eukaryotic cells, in contrast to prokaryotes, are characterized by their internal complexity and the presence of membrane-bound organelles. The term “eukaryote” means “true nucleus,” highlighting the defining feature of these cells: the nucleus, an organelle that houses the cell’s DNA. This compartmentalization allows for specialized functions to be carried out within different regions of the cell, increasing efficiency and complexity.

Key Features of Eukaryotic Cells

Eukaryotic cells share the basic components with prokaryotes – plasma membrane, cytoplasm, and ribosomes – but they also possess a range of organelles that perform specific roles:

- Nucleus: The control center of the cell, containing the DNA organized into multiple linear chromosomes. The nucleus is enclosed by a double membrane called the nuclear envelope, regulating the passage of molecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm.

- Organelles: Membrane-bound compartments within the cytoplasm, each with a specialized function. Examples include:

- Mitochondria: The “powerhouses” of the cell, responsible for generating ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the cell’s primary energy currency, through cellular respiration.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): A network of membranes involved in protein and lipid synthesis and transport. The ER can be rough (studded with ribosomes) or smooth (lacking ribosomes).

- Golgi Apparatus: Processes and packages proteins and lipids synthesized in the ER, preparing them for transport to other organelles or secretion from the cell.

- Lysosomes: Contain digestive enzymes to break down cellular waste and debris.

- Peroxisomes: Involved in various metabolic reactions, including detoxification and lipid metabolism.

- In plant cells: Chloroplasts (sites of photosynthesis), vacuoles (storage and maintaining turgor pressure), and a cell wall (different composition from prokaryotic cell walls).

This intricate internal organization allows eukaryotic cells to perform a wider array of functions and achieve greater complexity compared to prokaryotic cells.

Cell Size: A Matter of Scale

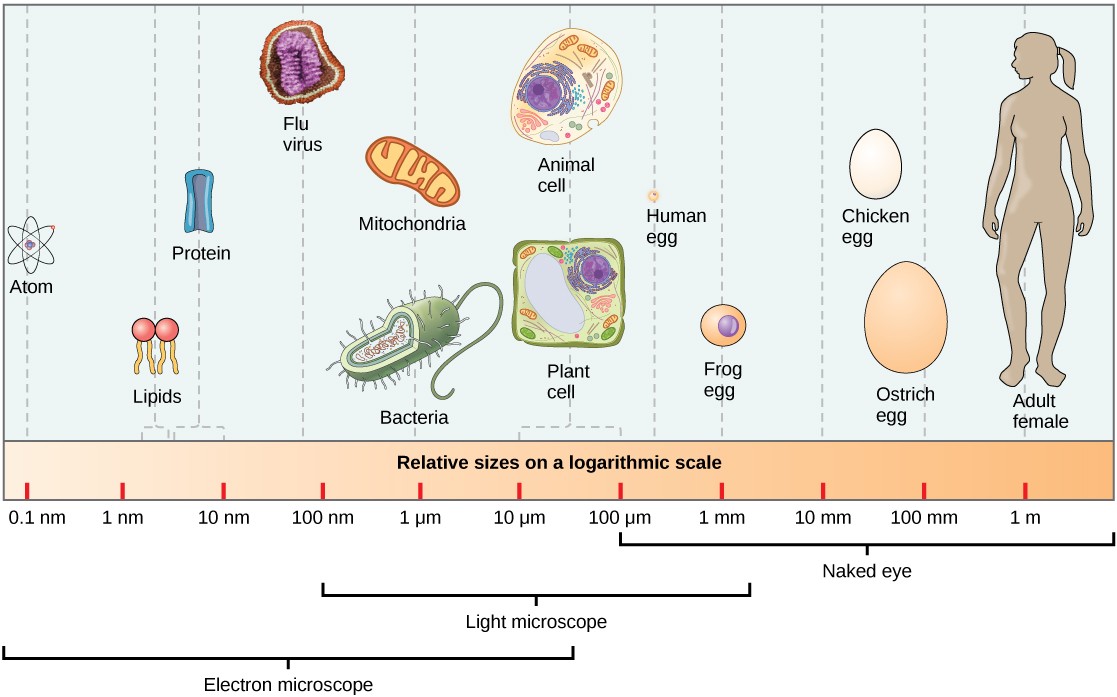

Size is another significant differentiating factor between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Prokaryotic cells are typically much smaller, ranging from 0.1 to 5.0 µm in diameter. This small size facilitates rapid diffusion of molecules within the cell, supporting their metabolic needs despite the lack of organelles.

Eukaryotic cells, on the other hand, are significantly larger, typically ranging from 10 to 100 µm in diameter. Their larger size is made possible by the presence of organelles, which compartmentalize functions and enhance transport efficiency within the cell. The increased surface area to volume ratio in smaller prokaryotic cells is advantageous for nutrient uptake and waste removal, while eukaryotic cells have evolved internal transport systems and structural adaptations to manage their larger size.

Key Differences Summarized

To clearly highlight the compare and contrast of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, here’s a summary of the key distinctions:

| Feature | Prokaryotic Cells | Eukaryotic Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | Absent (nucleoid region) | Present (membrane-bound) |

| Organelles | Absent (membrane-bound) | Present (membrane-bound) |

| Cell Size | 0.1–5.0 µm | 10–100 µm |

| DNA Organization | Single circular chromosome | Multiple linear chromosomes |

| Cell Wall | Usually present (peptidoglycan in bacteria) | Present in plant cells and fungi (composition varies), absent in animal cells |

| Ribosomes | Smaller | Larger |

| Complexity | Simpler | More complex |

| Examples | Bacteria and Archaea | Animals, Plants, Fungi, Protists |

Conclusion: Two Strategies for Life

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells represent two fundamental strategies for cellular life. Prokaryotic cells, with their simple yet efficient organization, are masters of adaptation and rapid reproduction. Eukaryotic cells, with their complex internal structure and organelles, are capable of greater specialization and complexity, forming the basis of multicellular life. Understanding the compare and contrast of these two cell types provides a foundational understanding of biology and the diversity of life on Earth.