Introduction

The depths of the ocean harbor creatures of fascinating adaptation, none perhaps as intriguing as the angler fish. This deep-sea denizen, with its bioluminescent lure, attracts prey in the dark abyss, a clever strategy for survival. Interestingly, in a completely different realm – the world of recreational fishing management – we also encounter “anglers,” but of the human variety. And much like understanding the angler fish’s hunting behavior, understanding the “reporting behavior” of human anglers is crucial for effective resource management. Just as the angler fish uses its unique biology to thrive, human anglers operate within a complex web of motivations and demographics that influence their participation in data reporting programs. This article delves into the human dimensions of angler reporting, drawing parallels, albeit metaphorical, to the captivating angler fish, and explores how understanding angler characteristics can “lure” them into better reporting practices.

The effective management of recreational fisheries relies heavily on accurate data regarding fishing effort and catch. For decades, programs like California’s Steelhead Report and Restoration Card (SRRC) have been implemented to gather this vital information through angler self-reporting. However, a persistent challenge plagues these programs: low angler report card return rates. This lack of response raises critical questions about the representativeness of the collected data and the potential for nonresponse bias. Just as scientists study angler fish to understand their role in the marine ecosystem, researchers are increasingly focusing on the human dimensions of fisheries, seeking to understand the anglers themselves. Who are these anglers? What are their characteristics? And how do these factors influence their willingness to report their fishing activities?

This article, based on a comprehensive study of California’s SRRC program, explores the demographic and behavioral attributes of anglers and their relationship to report card return rates. By analyzing data from 2012 to 2019, we aim to shed light on the factors that predict angler reporting behavior and identify potential strategies to improve data quality and program effectiveness. While the angler fish uses its lure to attract prey, we aim to find the “lures” that can motivate human anglers to become more active participants in fisheries data collection, ensuring the long-term health of our aquatic resources.

Understanding Angler Reporting: Why It Matters

Gathering data from recreational anglers is essential for sustainable fisheries management. Just as understanding the feeding habits of angler fish helps maintain the balance of the deep-sea ecosystem, understanding angler behavior is vital for managing fish populations in recreational fisheries. Fisheries managers utilize angler-provided data to track fishing effort, estimate catch rates, and assess the overall health of fish populations. This information is then used to inform regulations, set fishing limits, and implement conservation measures.

Self-reporting methods, such as catch cards and online surveys, are cost-effective tools for collecting angler data across large geographic areas. However, these methods are susceptible to nonresponse error, which occurs when anglers fail to submit their reports. This nonresponse can lead to biased data if anglers who do report differ systematically from those who do not. Imagine trying to understand the angler fish population by only studying the ones that are easily observed – you might miss crucial information about the shyer or deeper-dwelling individuals. Similarly, in angler surveys, if only certain types of anglers are reporting, the resulting data may not accurately represent the entire angler population.

Nonresponse bias can manifest in two forms:

- Unit nonresponse: An angler does not return the report card at all.

- Item nonresponse: An angler returns the card but leaves some sections incomplete.

Studies have consistently shown that anglers who respond to surveys tend to be more avid fishers, meaning they fish more frequently and are often more successful than non-respondents. This disparity can skew fisheries data, leading to inaccurate assessments of fishing pressure and catch rates. Therefore, understanding the factors that contribute to nonresponse and developing strategies to mitigate it are crucial for ensuring the reliability of angler-based data collection programs.

Analyzing Angler Demographics and Reporting Trends

To understand the human dimensions of angler reporting, a study was conducted using data from California’s Steelhead Report and Restoration Card (SRRC) program. This program requires anglers fishing for steelhead to possess a report card and record their fishing activity. Data from 2012 to 2019 were analyzed to identify trends in reporting rates and explore the influence of angler demographics and behavior on their likelihood of reporting.

Data Collection and Processing:

The study utilized data from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Automated License Data System (ALDS), which houses information on fishing licenses, permits, and angler report cards. Two primary datasets were extracted:

- Licensed steelhead report card customer information.

- SRRC angler-reported effort and catch data.

These datasets were combined and processed to create a comprehensive dataset for analysis. To address potential issues of pseudo-replication (where one angler might purchase multiple cards), the data were collapsed to represent a single “annual report” outcome per angler per year, based on their overall reporting status (reported or unreported).

Statistical Analysis:

Linear regression analysis was employed to examine trends in overall reporting rates and online reporting rates over the study period. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean reporting rates across different angler demographics, including:

- Age groups: Categorized into four groups representing different life stages (1-19, 20-39, 40-64, 65+ years).

- Area of residence: California residents vs. non-residents.

Logistic regression was used to evaluate the influence of several independent variables on the odds of angler reporting. These variables included:

- Age: Continuous variable representing angler age.

- Region: Categorical variable representing CDFW geographic regions based on the angler’s county of residence.

- License Type: Categorical variable (lifetime or annual).

- Year Quarter: Categorical variable representing the quarter of the year the card was purchased.

- Purchase Frequency: Categorical variable (frequent or infrequent card purchaser).

Key Findings:

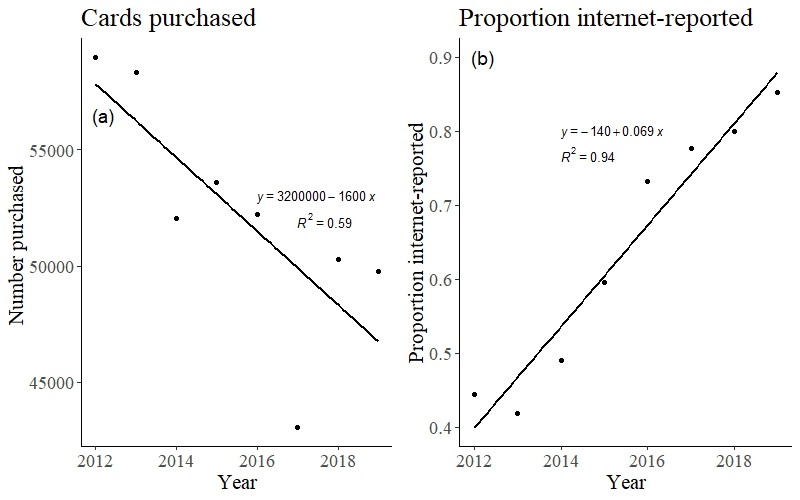

- Temporal Trends: While the total number of report cards purchased showed a slight negative trend over time, there was no significant trend in overall reporting rates. However, a significant positive trend was observed in the proportion of anglers reporting online, indicating an increasing preference for digital reporting methods.

- Age and Reporting Rates: Reporting rates varied significantly across age groups, with older anglers generally exhibiting higher reporting rates. Specifically, anglers in age groups 3 (40-64 years) and 4 (65+ years) showed significantly higher reporting rates compared to younger age groups.

- Residence and Reporting: California residents had significantly higher reporting rates than non-residents.

- Online Reporting by Demographics: Younger adults (age group 2, 20-39 years) were more likely to use online reporting compared to older adults (age group 4, 65+ years). However, overall reporting (including both mail-in and online) was still highest among older age groups.

- Logistic Regression Results: The logistic regression model identified several significant predictors of angler reporting:

- Age: Older anglers were significantly more likely to report.

- License Type: Lifetime license holders were more likely to report than annual license holders.

- Purchase Frequency: Frequent card purchasers were more likely to report than infrequent purchasers.

- Year Quarter: Anglers purchasing cards in the fourth quarter (October-December) were more likely to report, while those purchasing in the second quarter (April-June) were less likely.

- Region: While statistically significant, the region of residence had a relatively minor effect on reporting likelihood.

Discussion: “Luring” Anglers into Better Reporting

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the human dimensions of angler reporting and offer potential strategies to improve data collection efforts. Just as understanding the angler fish’s lure helps us appreciate its hunting strategy, understanding the motivations and characteristics of human anglers can help us “lure” them into better reporting practices.

Age and Avidity Matter:

The study confirms that older and more avid anglers are more likely to report their fishing activity. This aligns with findings from other studies and suggests that anglers who are more invested in fishing and perhaps more aware of conservation efforts are more inclined to participate in reporting programs. This is similar to how more experienced angler fish might be more successful hunters due to their developed skills and adaptations.

Online Reporting: A Modern “Lure”:

The increasing trend of online reporting, particularly among younger adults, highlights the importance of digital accessibility. Online platforms offer convenience and ease of use, appealing to a tech-savvy demographic. This is akin to angler fish adapting to their environment by developing bioluminescence – a modern adaptation for data collection is online reporting.

Time of Year and Reporting Behavior:

The finding that anglers purchasing cards during the steelhead fishing season (Q1 and Q4) are more likely to report suggests that engagement with the fishery itself is a motivator for reporting. This is intuitive – anglers actively fishing are more likely to remember and prioritize reporting their catch.

Management Recommendations: Strategies for Improvement

Based on these findings, several management recommendations can be proposed to enhance angler reporting rates and data quality:

- Targeted Outreach to Younger Anglers: Recognizing the lower reporting rates among younger anglers, CDFW could focus outreach and education efforts specifically on this demographic. Promoting online reporting platforms through social media and other digital channels popular with younger audiences could be particularly effective.

- Reminder Systems for Non-Respondents: Implementing reminder systems, particularly for anglers who have not yet reported, could nudge them towards compliance. Email reminders, given the increasing preference for online communication, could be a cost-effective approach.

- Investigating Non-Response Motivations: To further refine outreach strategies, conducting surveys to understand the reasons behind nonresponse is crucial. Asking non-reporting anglers why they did not return their cards can reveal barriers to reporting and inform the development of more effective solutions. Are they lacking time, unaware of the importance, or facing technical difficulties? Understanding these reasons is key.

- Exploring Incentives and Gamification: While penalties can be considered, exploring positive incentives might be a more palatable approach. Gamification elements within online reporting platforms, or small rewards for timely reporting, could potentially increase engagement and motivation.

- Follow-up Surveys for Nonresponse Bias Correction: To address the potential for nonresponse bias, implementing follow-up surveys of non-respondents is essential. This would allow for a comparison of catch and effort between respondents and non-respondents and potentially enable statistical weighting to correct for bias in the overall data.

- Consider Smartphone App Reporting: Building on the success of online reporting, exploring a smartphone app for reporting could further enhance accessibility and real-time data collection. Just as angler fish have evolved sophisticated biological tools, modern technology offers advanced tools for fisheries management.

Conclusion: Learning from Anglers, Both Fish and Human

Just as the angler fish captivates us with its unique adaptations for survival in the deep sea, the behavior of human anglers presents its own set of fascinating complexities for fisheries management. This study highlights the importance of understanding the human dimensions of angler reporting and provides valuable insights into the demographic and behavioral factors that influence reporting rates.

By recognizing the characteristics of anglers who are more and less likely to report, and by embracing modern technologies and targeted outreach strategies, fisheries managers can effectively “lure” anglers into greater participation in data collection programs. Improving angler reporting is not merely about collecting numbers; it’s about fostering a collaborative approach to fisheries management, ensuring the long-term health of our aquatic resources for both current and future generations of anglers – both human and perhaps, metaphorically, fish as well. Just as we study the angler fish to understand the ocean’s mysteries, understanding human anglers is key to responsible stewardship of our fisheries.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and all individuals who contributed to the original research study and data collection. Their efforts are essential for the ongoing management and conservation of California’s steelhead fishery.

Literature Cited

(Literature cited section remains the same as the original article)